If we focus on the tree in our mind’s eye, the upright and striking form of its physical presence comes forth. Its vertical line moves our eyes upward to the fruit and leaves of its branches, to the skies above. The trunk is the main organ of the tree. Its rigid woody structure provides the central support for all that happens to the tree. It supports the crown and functions as a conduit, carrying water and miner- als up from the ground and transporting sugars from the leaves to feed the root system.

The bark of the trunk protects the living tissue from damage by the elements, animals, bacteria, and fungi, but this armor isn’t without feeling or sensitivity. Tree trunks can register light. “Most tree species have tiny dormant buds nestled in their bark” that receive light waves and can sense the amount of daylight available to the tree, thereby orienting it in time by length of days even when its branches are bare.

The trunk comprises four layers: heartwood, xylem, cambium, and phloem. Heartwood is the hard core, made up of old xylem layers that have died and become compressed by the newer outer layers. The xylem is also called sapwood and carries water and minerals up the trunk. The cambium is a thin layer where new cells develop to either become xylem, phloem, or more cambium. A cambium layer is turned into xylem once each year, creating an annual ring around the trunk. Just outside the cambium, the phloem moves sugars from the leaves down to the roots. As it dies, the phloem forms the bark.

Looking back at our diagram, we see that the trunk of the archetypal tree represents the mortal sphere. Here, we rise up and manifest new ways of being from the feelings and beliefs we cultivate in our cycles of descent. The intuition, impressions, and visions nurtured in the chambers of the soul come to be birthed—to gain physicality and form in the visible world. In community and communion, new patterns of interaction emerge. We learn how to love more fully from a heart nurtured and, thus, open, in healthy vulnerability.

The vertical axis of the trunk symbolizes a bridge between our fledgling knowledge and the divine wisdom in the heavens above. Our earth-bound wisdom is gathered in the realm of the trunk, which leads us to celestial understandings. So while, in our root work, we strive to relieve our souls of things that may cause harm, we are always in the process of uncovering our true selves, of moving toward wholeness and greater understanding—reckoning at the roots that affects the health of our trunk and branches. As we continue to access the healing powers of the divine, we see more and more clearly the reality of our lives.

In this way, Mother God teaches that “wisdom is not knowing more, but knowing with more of you, knowing deeper.” Tapping into divinely feminine traits with the guidance of our Mother creates a grounding and depth to our experience of the world and of ourselves. She calls us to a deeper state of awareness. Our senses become heightened. We hear more acutely and see more sincerely into the truth of all things. Importantly, we learn to trust our bodily, experiential wisdom. We begin to understand the balance of the divinely feminine and divinely masculine aspects of ourselves as we learn how the mind, spirit, and body intersect. The Mother encourages this multidimensional integration of all facets of the self, just as the tree has many interactive layers. These are complex energies that emanate from one living being to another, and they bind us together in ways that are both eternally consequential and somewhat elusive to our full understanding in mortality. As we learn to weave these different intelligences together, we come to see that we are here on Earth to deepen our souls in an act of co-creation with divinity.

Our Mother is able to help us integrate different intelligences because She is not limited to the symbolic. If we expand our view from seeing Heavenly Mother as secondary to the Father or as hidden from our view, we can see Her as Creatress. Her spirit is infused in the very fabric of creation, forever present in the living, breathing arc of life that surrounds us every moment. I have felt this holy feminine energy and presence in the natural world speaking to my soul, soothing some of my most anguished seeking. As Christ is in and through all things, the light of truth, consider how He rose to this astonishing potential. Consider His Mother’s contribution to His formation and ascent. Through all things, the Mother of creation, our Mother, with our Father and Jesus, emanates from the creation of Her own hands (D&C 88:6). She is present in the very dirt under our feet. From the first parting of the firmament over the land, and like the parables woven from Jesus’s lips, She thrives. In the wisdom of the land She speaks. In the howl of the wolf, the quaking of tectonic plates, in the breaking down of chlorophyll, the revelation of colors long buried now vibrant, the voice of the Mother is in the wild all around us and the wild within us. We are wild, not in the word’s pejorative sense meaning out of control but in its original sense: striving to live a natural life, one full of innate integrity and healthy boundaries. Living a natural life is how we could describe our acceptance of self. It means cultivating a practice of surrender to our inner knowing in order to stay grounded in what is real.

Every body is unique and will access its innate knowing differently. There are many tools to use, both physical and spiritual, to help you tap into what your body is telling you. We are taught to listen to the Spirit, but the Spirit operates through the body, and there are many signals that we may receive, telling us we are on track or that we need to fine-tune the ways we are engaging with the world. For example, it is possible to speak with our heart. Many ancient cultures know this. We can speak with our heart as if it were an intimate friend. In modern life, we have become so busy with our daily activities that we have lost this essential art of taking time to converse with the heart. What does your heart want you to remember? What does it need you to feel? Don’t evaluate what comes up. Sit in stillness and allow the heart’s wisdom to rise up above the noise of passing thoughts, above the clamor of outside stimuli. Holding yourself in kindness, not judgment, will allow your heart to reveal itself to you, whether for the first time or after a long separation. With time, you will learn how to trust it, and it will learn to trust you.

I didn’t know until I was twenty-nine that my heart has its own voice. I always thought the idea of listening to one’s heart was a powerful metaphor for honoring our uniquely divine essences, but I had no idea of the heart as a sort of sovereign, independent voice with its own desires of which I could be unaware. At the end of my graduate studies, a series of incredibly poignant answers to prayers and unmistakable divine direction led me back to a man I had dated two years before. The situation was more difficult this time, and part of me resisted the potential fallout if the relationship didn’t ultimately work. I remember sitting next to my now husband on our second first date, watching a movie and feeling my heart speak. Over the course of a few months, it had slowly been stirring and telling me to pay attention. I’ve often felt the Spirit begin in this heart space, prompting words and actions, but I had never experienced my heart interjecting its own volition. This time it did. It said, This is what we have been waiting for.

Trunk as Axis Mundi

The trunk of the cosmic tree is the axis mundi (world axis). A vertical marker, it is the point around which the visible world revolves. Itis the changeless, cosmic center. The center’s inherent stillness represents entrance into divine rest in this life. In the constancy of the sacred center, we feel the presence of the sacred within the daily mundane, carrying us through strains and sorrows. Being able to feel this strength beneath the worry and desires of the moment, their projection into the past and onto the future, provides spiritual and physical orientation in the world.

Because the world axis is “the point at which all things come together,” it is expressed as sacred objects and structures across the world: poles, totems, pyramids, ziggurats, and temples, to name a few. These spaces are paired with sacred rituals and ceremonies that open the profane reckoning of time to a cosmic, or eternal, framing. A beautiful example of this pairing is found in the festivals that occur on May Day or Pentecost, focused around the maypole. These festivals hark back to the recreation of the cosmos and the celebration of the changing of the seasons. The simultaneous dancing around the maypole and interweaving of colorful bands allows dancers to participate in creation—the weaving together of the world—as they symbolically reinitiate the annual experience of spring and act out a ritualized dramatization of creation. Life springs from death again and again, eternally, infinitely; the finite is made eternal.

Mother as Axis Mundi

Our own Latter-day Saint temples serve as sacred centers, world axes; they add a cosmic dimension to time ritualized, fulfilling their essential role as the conduit between heaven and earth, God and humanity. Participating in our sacred ceremonies can feel like entering the timelessness of eternity because they are designed to invoke that feeling. Our ritual partaking opens up realms of sacred time through which we are actors in the creation of the world, over and over. Through language and gestures, an effervescent union of profane and sacred realms emerges. As the Gods ordered the world of the Garden around trees that pointed to spiritual tasks that help us grow, we participate in the world of the Garden through these rituals that orient and reorient us to what matters most. While we feel a gap in our temple worship as it relates to the Mother, She was not always absent from sacred spaces. Her influence can be traced to the Garden of Eden, which was the center of the world in the beginning and the center of the Father and Mother’s care for humanity.

As the Mother’s body is the trunk of the tree in our chosen metaphor, we see Her image imprinted on the image of the cosmos reflected in/by many sacred spaces. Looking at the origins of our own temple worship, we find that the feminine face of the divine is rooted deeply there. In the first Jerusalem temple, “the earliest Israelites worshipped the divine mother Asherah along with the God of Israel,” says Rabbi Jill Hammer. As “the site of origin of divine wisdom, the means of ascent into the heavens,” the world tree or world axis was recognized as Mother God. Known by many names to the Israelites, including Lady Wisdom, Shaddai, and Asherah, She spoke with the Father and the Son from the cosmological center of the Israelites: the Holy of Holies. The Holy of Holies was constructed as a perfect cube and lined with gold to represent the light and fire of the divine presence (Prov. 8; 2 Chr. 3:8). It was the heart of the temple and represented the highest order of divine power: an understanding of the mysteries of becoming.1 It was home to the divine.

Abraham’s form of temple worship was altered by King Josiah in the seventh century BCE to comply with the Book of the Law (2 Kings 22:8). This book was discovered during the temple’s renovation and is either a version of Deuteronomy or an extra canonical law code. The supporters of this law code are referred to as the Deuteronomists, and their temple and worship reforms “caused the loss of what were likely many plain and precious things. Among these were the older ideas, symbols, possibly entire rituals, and forms of words from the temple as its adherents had known it, including the Lady Wisdom.” During the purges, every sign of the Mother in the temple, including the original menorah, was removed, burned, or destroyed.2 In an attempt to prize written law over Wisdom and heart, the Deuteronomists did their best to erase Her from scripture, sacred spaces, and a people’s shared memory.

Our eminent Mother remains scant in Latter-day Saint doctrine, absent in ceremony, and hasn’t been fully included in theological discourse. Yet, She is not entirely erased from scripture. “The mysterious female figure of Proverbs, Lady Wisdom, may be a version of Asherah, since she is called ‘happy’ (asher) and described as a tree, as Asherah was depicted as a tree.” Proverbs 8 reveals Her as assisting the Creator in forming the world: “When he established the heaven I was there, when he drew a circle on the face of the deep, when he made firm the skies above . . . I was beside him, like an architect [Hb., ‘amon]” (Prov. 8:27–28, 30, RSV). The Greek translated ‘amon as harmozousa, meaning “the woman who holds things together” or “the woman who keeps things in tune” (Prov. 8:30, LXX), which implies that She was remembered as the bond of the everlasting covenant.3

As much as the Mother was known as the Creatress, she was also known as the retribution for covenants broken, the curse inherent in the severing of relational bonds—in harming each other—the refusal of honoring the powers of creation born from Her womb into the world. At the time of the purges, biblical scholar Margaret Barker notes, groups of believers of the older faith (such as Lehi and his family) left or were driven from Jerusalem and, in their exile, continued the older forms of Abrahamic worship. These older beliefs are found in texts such as the Book of Weeks and the Apocalypse of Enoch, as well as in the Book of Mormon. Close readings of the Bible reveal evidence for the older traditions in Ezekiel, Psalms, Micah, Amos, Hosea, Jeremiah, and parts of Isaiah. Many of these prophets condemn “not only foreigners, enemies, or invaders from outside the kingdom but also the changes they saw from the religion of Abraham to that of Moses, and his Law.” According to Barker, “The sins of Jerusalem that Isaiah condemned were not those of the ten commandments, but those of the Enoch tradition: pride (e.g., Isa. 2:11, 17), rebellion (e.g., Isa. 1:23, 1:28, 5:24) and loss of Wisdom (e.g., Isa. 2:6, 3:12, 5:12).” Chapter one of the book of Proverbs gives voice to rejected Wisdom and could well have been set in the period between the rejection of Wisdom by Josiah and the destruction of the city by the Babylonians:

How long will scoffers delight in their scoffing, and fools hate knowledge? Give heed to my reproof and I will pour out my spirit on you . . . because I called and you refused to listen . . . and you have ignored all my counsel. I will laugh at your calamity, I will mock when panic strikes you . . . when distress and anguish come upon you. Then they will call upon me but I will not answer, they will seek me diligently but they will not find me (Prov. 1:22–28).

We see the evidence of wisdom’s rejection in the Book of Mormon as well. Before we get there, let’s look at some of the signs pointing us to Asherah, Lady Wisdom, in the Book of Mormon. Daniel C. Peterson, among other scholars, makes the connection between the tree of life in Lehi’s vision and Asherah. Lehi and his family were contemporaries of the prophet Jeremiah who lived during the purges of the Jerusalem temple. Peterson argues that Lehi and Nephi would have known of Asherah and Her symbol as the tree of life and that this association would make sense of the instant recognition by Nephi of the tree as “the love of God.” In Peterson’s words, “Nephi’s vision reflects a meaning of the ‘sacred tree’ that is unique to the ancient Near East. Asherah is . . . associated with biblical wisdom literature. Wisdom, a female, appears as the wife of God and represents life.”

Some of the Israelite descendants turned away from the Mother into wickedness, while others learned from Her wisdom. In Mosiah 8, King Limhi has just learned about seership and connected its absence to the children of men hardening their hearts against wisdom. Perhaps wisdom and seership were still connected in his mind. Perhaps he inherited some knowledge of Her: “O how marvelous are the works of the Lord, and how long doth he suffer with his people; yea, and how blind and impenetrable are the understandings of the children of men for they will not seek wisdom, neither do they desire that she rule over them” (Mosiah 8:20).

Our Mother is still severed from the temple, our world tree taken from our most sacred spaces—the words, gestures, and signs of the Mother in our temple missing. If She, the embodied ordinances of creation, Lady Wisdom Herself, is not at the center of our creation narrative, I wonder how we can possibly speak words with the power to bind. Although we have lost the ability to translate it, Her symbolism is still encoded in the temple narrative of the Garden. Its decoding is essential to the gathering of Israel and of truth, wherever it can be found. To prepare for the return of the Mother to the Garden, to the temple, to the center of our spiritual framing of the cosmos—to the center of our hearts—we begin by seeing Her sign separated from the signification: in the temple video and the painted walls. With a new reading of the Garden narrative, can you begin to see Her there? Even if we aren’t being taught or aren’t enacting the rituals about Her?4

It’s no wonder when we don’t see creation as mothered and upheld by a mother that we could make shortsighted decisions; we lack a vision of what a tree could be. And so we have made decisions systemically that have cascading unforeseen effects on our spiritual and thus physical health. It becomes evident in how our severed ideas of femininity affect our ability to properly see and understand the bodies of women.

Discussion Question:

Some of the most holy moments in Christian and Mormon history occurred in a grove or with a tree. How does seeing the Divine Mother symbolically as the olive grove of Gethsemane, the cross from which Christ’s body hung, the Tree of Life witnessed as the source of eternal life by Lehi and Nephi, and the Sacred Grove which surrounded Joseph Smith as he witnessed the heavens open, change your

understanding of Divinity?

Join our online chat community.

Kathryn Knight Sonntag is the Poetry Editor for Wayfare and the author of The Mother Tree: Discovering the Love and Wisdom of Our Divine Mother and The Tree at the Center.

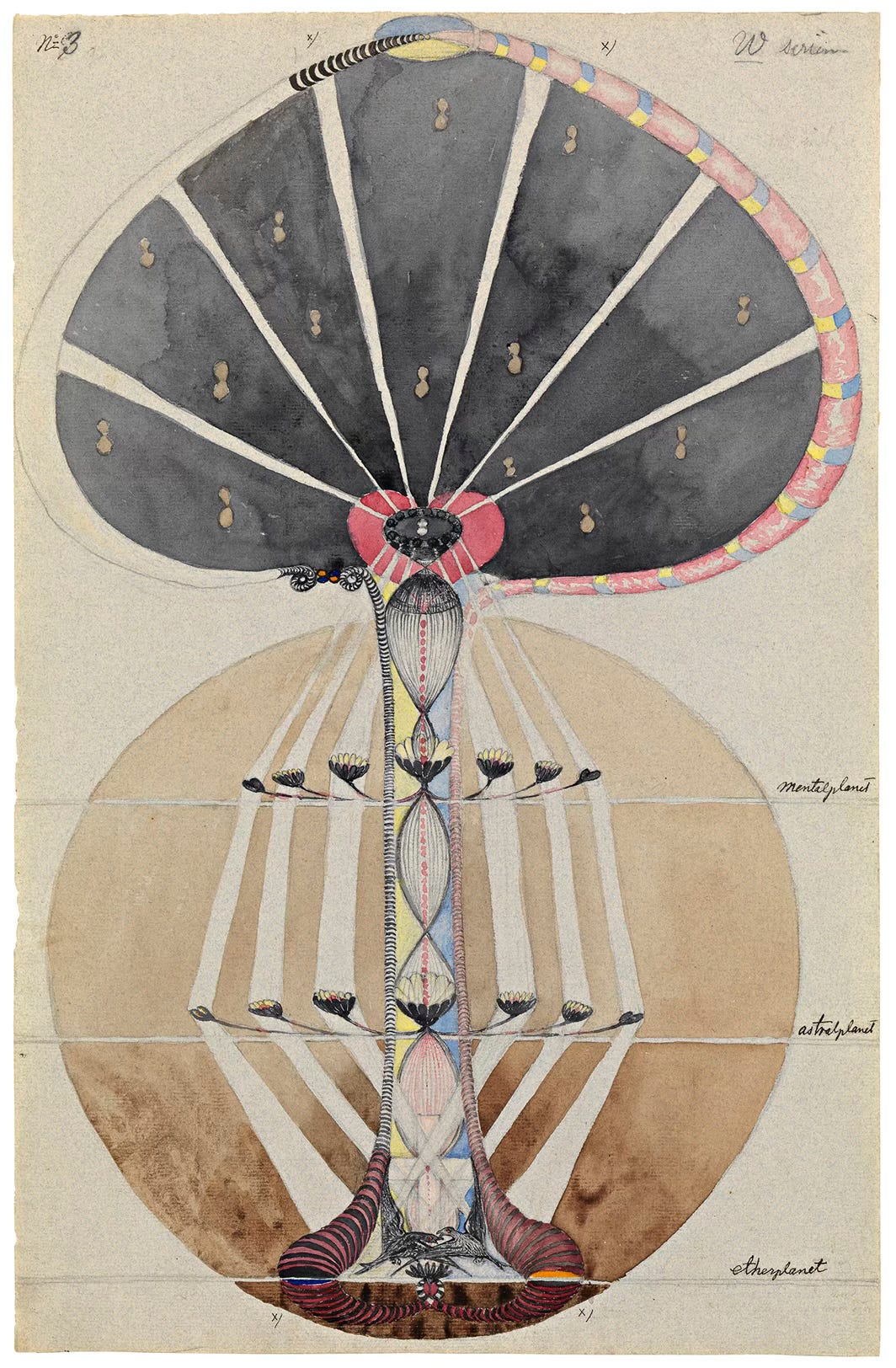

Art by Hilma af Klint.

Margaret Barker writes, “A key theme in the Qumran Wisdom texts was the raz nihyeh, which probably means ‘the mystery of existence’ or ‘the mystery ofbecoming’ that the holy of holies represented. The one who sought Wisdom was exhorted to ‘Gaze upon the raz nihyeh and know the paths of everything that lives.’ Vision was fundamental to Wisdom.” See The Mother of the Lord, Volume 1: The Lady in the Temple (Bloomsbury, 2012), 107.

The menorah in the temple was a symbol of the high priesthood and of the high priest’s relationship to the Lady. See Barker, Mother of the Lord, 65. Elsewhere Barker also asserts that the original menorah in Solomon’s Temple may have stood in the Holy of Holies: “The menorah that represented the tree of life was restored to the temple. There had been a menorah in the second temple, as can be seen from the one depicted among the temple loot on the arch of Titus in Rome. Nevertheless, there was acultural memory that this was not the true menorah: maybe it had stood in the wrong part of the temple, or maybe it no longer represented the tree of life.” Barker, http://www.margaret-barker.com/Papers/RestoringSolomon.pdf, 11. According to Barker, “The Lady’s great symbol was the tree of life, represented in the old temple by the menorah which originally stood in the holy of holies, the most sacred part of the temple. When John had a vision of the old temple restored, he saw that the tree of life had returned to the holy of holies (Revelation 22.1–5).” Barker, http://www.margaretbarker.com/Papers/TheLadyoftheTempleinaJordanleadbook.pdf.

Margaret Barker, “Wisdom and the Stewardship of Knowledge.” Scriptures suggest that the meaning of covenant was connected with creation’s order and stability: “Behold I establish my covenant with you and your descendants after you, and with every living creature that is with you . . . the everlasting covenant between God and every living creature of all flesh that is upon the earth” (Gen. 9:9–10, 16). “The earth mourns and withers . . . for they have broken the everlasting covenant” (Isaiah 24:5). Breaking the everlasting covenant, then, would mean destroying the bonds of creation. It would be a rejection of the feminine aspect of deity.

I go into more detail later in the book about what is missing in the temple space.