I was twenty-two years old when I first held a dead body. He was freshly gone. One moment talking pleasant nonsense with his family and friends over beers on the Moscow–St. Petersburg express train, the next moment fibrillating between the bench and the table. They’d come for a holiday from their home in Spain to see the once-Soviet land of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, of Peter the Great and Stalin the Terrible. If memory serves, the tourist’s name was Alejandro. He called Madrid home.

I was majoring in linguistics then. I’d secured funding to study Russian syntax between my sophomore and junior years of college and had quickly realized that, in freshly post-Soviet Moscow, I may as well enjoy the country as try to get anything meaningful done in the empty offices of a Russian summer. So I headed to Petersburg with a newfound friend, the warm and gracious Zhenya.

I’d felt called to be a physician during my freshman year of college. I thought I should be a classics professor, but God had other plans—and I was trying to be obedient. This odd feature of my early adulthood meant that even though I was primarily studying the subsurface structures of language, I was also a “pre-med” student. I’d learned the rudiments of CPR as part of volunteering at a rehabilitation hospital beside the Italian quarter in Boston’s “north end.”

I’d seen enough of the weeds Soviet Communism had sown in Russian society to be skeptical of the quality of their medicine (an assumption that proved, alas, quite true when I returned years later to do public health research). So when a train official ran through our second-class car yelling “kto-nibud’ vrach?” I figured that I was as much a “doctor in the house” as anyone else they’d find that night. So I called out, “Da,” and ran after him, lurching from coach to coach through the weary clackety-clack of the ramshackle train.

When we arrived in the first-class compartment, all was chaos. People shouting and crying in Russian and Spanish, and Alejandro’s friends pushing on his chest without a discernible rhythm to their efforts. If Harvard life had taught me anything, it was to project competence even where I had none. So I took control, modeling what I thought was effective CPR and helping them count their chest compressions—“uno, dos, tres, cuatro, cinco”—over and over. We kept this up for an hour, until the train stopped beside a godforsaken town covered in long grass and blank darkness. Two medical professionals placed a breathing tube into Alejandro’s windpipe, splashed some lidocaine through that same tube, and pronounced him dead in one languorous shudder of their shoulders.

At first, maybe, Alejandro looked like he was in a deep, chemical sleep. I wondered whether we could still consider him alive if our efforts were circulating his blood. Maybe so. But as the minutes stretched to an hour, his skin grew pale and ashen, almost woody. He only moved when we pushed his chest or grabbed his chin. His body was an object, to borrow the language of scripture, that could only be acted upon. He slumped further from life with every additional minute his heart failed to beat on its own.

Once I’d got the rhythm of chest compressions and breathing settled, I turned to Alejandro’s wife and young son. While I had learned Russian in college, I’d made it through two years of high-school Spanish and decided in that moment that I was an honest-to-goodness polyglot. I began to explain to the worried Spaniards what was going on and how important our CPR was. I complimented their friends for their great work at chest compressions. The incipient widow stared at me, mystified. The boy watched his mother’s knee.

The tour guide interrupted me in Russian. “They only speak Spanish.”

“I know,” I said, “that’s why I’m speaking Spanish.”

The officials began to laugh like a Greek chorus. “You’ve been speaking Russian the whole time,” the interpreter explained. My cheeks flashed pink. In the intense emotion of the moment, my brain had dived into the “foreign language” pond, and at that time in my life, that body of water could only hold Russian. I tried for a painful moment, as Alejandro’s friends continued to count and push, to get some actual Spanish out. “Lo siento” was all I could manage, I’m sorry. Indeed.

I had witnessed sorrow before. My own father died when I was eighteen, also with a sudden cardiac arrest, also with CPR, but in a hospital in the Wasatch Mountains rather than a train in the Russian countryside. I was thousands of miles away and didn’t even make it home for the funeral. I never saw his dead body. Death wasn’t the only sadness there: I’d had run-ins with vaguely suicidal depression as a teen, and I had struggled under the awful weight of poverty and my parents’ mental illness. But I’d never seen grief like that of the widow and her son.

After we arrived in St. Petersburg, the railway officials mocked my worry that leaving Alejandro’s corpse at room temperature would accelerate his decay. “His first body,” they laughed as they drank vodka and ate dried fish around a long table, their gaze not making it all the way to me or the Spaniards. The interpreter explained that the Spanish consulate would assure that Alejandro’s body would be repatriated. But there the two Spaniards sat in a foreign country, surrounded by people who could not understand their words, beside the slowly decaying body of their beloved Alejandro. A widow and an orphan, strangers in a strange land. They yearned for the language of their homeland, for its familiar smells and sights and sounds. Above all, they longed for Alejandro to speak again, for any human sound to escape his throat.

There’s a lot happening in that memory from my first trip to Russia: life and death, bodies and spirits, homeland and exile, empathy and incomprehension. These themes have been with me for my entire life. If anything, I see them more clearly and consistently as I make my way through life’s middle ages with their various mournings and muddles and dislocations. We are never quite where we mean to be; we can never quite say what we mean to say. We are never quite who we mean to be. I feel these existential problems deeply as a Latter-day Saint, and I often wonder what the Restoration has to say and do with them.

That train ride told a related story about the troubled history of language. The specific details of Spanish and Russian kept the participants from understanding each other, both the bare words and their deep meanings. I knew from classes in historical linguistics that those two languages flowed from a single spring. This language, Proto-Indo-European, is what our ancestors spoke in the vastly open spaces between Europe and Asia five thousand years ago. Only two hundred generations have passed since then, but how far we have come from that place, that language, that time!

We see occasional fossils of that lost unity in the modern Indo-European languages. We mortals will one day be as dead as Alejandro—as the Spaniards would have it, muerto, or as the Russians say, myortvy. I’m not surprised that the word for death has changed so little over the millennia. I wonder sometimes when humans first started talking about death and the possibilities that lie beyond it.

I’m guessing that awful conversation came within a few hours of when they spoke their first words. That’s certainly how the Old Testament account of Eve and Adam in Eden has it. “Welcome to life, which is full of fruit and trees,” God says. “Here is knowledge, and here is death.” Our first parents chose both. In doing so, they became gods in exile, called to spend their lives stitching heaven and earth back together. That work, the work of gods in earth, is a project of translation.

This is not, I suspect, the typical preface to an academic talk on translation, even in the metaphysically charged spaces of the Restoration. Translation generally worries, as I do, about our Book of Mormon, our Bible, the scripture that I call the Egyptian Bible and others call the books of Abraham and Moses. I am not discussing Hebrew syntax, Arabic cognates, or apparent precedents in eighteenth- or nineteenth-century English texts. There will be nothing in this talk of Solomon Spaulding or Ethan Smith or Adam Clarke, and there will be nothing of proto-Isaiah, deutero-Isaiah, or Hugh Nibley. I find those topics interesting, and I will happily read the relevant scholarship as it is published. But they seem to me to stand beside the point of Restoration translation.

In Restoration thought, that single word, translation, effortlessly refers to the conversion of one text from a particular language community to another text for a distinct language community as well as the conversion of a human being such that she is able to tolerate the divine presence directly. There is both movement—the traditional etymology of trans-latio, or as the Greeks would have it meta-phorein—and transformation. Bodies and texts both undergo translation. In a sense, my work on translation in the Restoration is an attempt to understand the relationship between those two senses of translation. Are they in fact two separate words that look or sound the same? Could this, in other words, be a case of homophony or homonymy? Or are these two clusters of meaning in the intriguingly broad semantic scope of one fundamental word? To my eye, the last option is the closest to the truth: translation in these multiple senses is a single concept with deep unity. The fact that translation encompasses linguistic and human transformation is not, in my view, a vagary of historical etymology. Even when we aim to speak strictly of scripture, translation is bigger, and I believe better, than the movement of words from one group to another.

I’ve spent almost two decades thinking about translation in the early Restoration, pondering from the perspective of intellectual history and also, more quietly, from the standpoint of a human believer. My strange and stretching encounter as a college student with a dead Spaniard on a Russian train brings those possibilities into sharp focus.

I see in that story and in the Restoration legacy of translation the complementarity of body and spirit, the human posture between heaven and earth, and the failings of human communication. Navigating these channels is the work of translation. Working with those three basic ingredients—complementarity, exile, and fallen language—I believe we can bake a true and soulful understanding of scripture and translation. Understood this way, translation is a bulwark of the Restoration and the special light it sheds in the world. I will argue that these themes not only explore existential questions but also return to the traditional starting point of scripture in the world. If I may borrow rather predictably from T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets,

We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time. Through the unknown, remembered gate When the last of earth left to discover Is that which was the beginning; At the source of the longest river The voice of the hidden waterfall And the children in the apple-tree Not known, because not looked for But heard, half-heard, in the stillness Between two waves of the sea.

With that preface, we will leave traditional ideas about scriptural translation to explore complementarity, exile, and the failures of language. And then we will return to scripture to see it for the first time.

COMPLEMENTARITY

I’m well aware of, and have even participated in, ongoing debates about whether Latter-day Saints are materialist-monists or dualists. A traditional story says that we Mormons are monists. The available data suggest to me that Joseph Smith would have been mystified by the distinction. We are the merged complement of body and spirit, and that duality is embedded within a unity that embraces two worlds. One could, I suppose, fault Smith for not being more systematic about this. That would be a category error: Smith was not a systematic theologian and was not pretending to be. But diagnosing category errors is by now a too-common form of intellectual laziness. So, I’d like to wonder this objection through a bit, even if it is a category error. Whatever his lack of bona fides as a systematic theologian, Smith was the human vessel of a rich Restoration theology. That theology deserves to be considered carefully.

So, what did Smith actually say? In canonized aphorisms, he said that “all spirit is matter” but is of a “more fine or pure” type. He said much the same in a contemporaneous editorial in the church newspaper. From these two key documents, we see Smith proposing that what others call matter is actually coarse matter, and what others call spirit is fine matter. In other words, the duality of spirit and body is in fact a duality of coarse and fine matter.

There’s more than just the aphorisms, though, in this question of philosophical monism. There are also the mysterious instructions about shaking hands with humanoid apparitions canonized in the Doctrine and Covenants (section 129). The duality of coarse and fine matter extends into the taxonomy of non-ordinary beings—true angels can be touched, whereas honest pre-angels will demur from attempts to shake hands. Smith thought of the God (or Gods) called Elohim as enmeshed in the world with all of us, physical like us, coeternal with us. This theology of an embodied God entails the possibility that the lack of physicality splits the world of consciousness in two. And Smith follows that line precisely in his teaching that what separates Satan and his demonic hordes from angels and humans is the fact that they never materialize as physical beings. They never get bodies, never become coarsely physical. This is stark evidence, to my eye, of a deep duality of body and spirit. The Sons of Perdition (the only truly lost children of Restoration scripture) lose their embodiment precisely by aligning definitively with the souls that have lost the option of embodiment.

It should be abundantly clear that there is no credible path from Smith to the Gnostics, who radically prioritized spirit over matter. The essence of Gnosticism, expressed so clearly in its Docetist heresy, is Smith’s very definition of hell. Note that fact: the physical is a mandatory component of the celestial. To be a soul alone is to be lost forever.

I want to notice here that in this central complementarity, spirit is not superior to matter or mind better than body. Spirit is wonderful, true, and primary in the grand history of the cosmos, but spirit lacks the substance required of a divine being. And the physical is the prize of the Plan of Salvation. As many twentieth-century Saints would say, we come to earth to partake of a body (just as we partake of the Eucharistic body). Without that partaking, originary spirit is damned. So this persisting duality, what I prefer to call a complementarity, is not hierarchical in any familiar sense.

This complementarity of spirit and body mirrors a complementarity of divine and human. Recall that Elohim had to be mortal to become divine. We tend to focus on the sequential nature of the mortal-becoming-divine pathway, but we can also acknowledge that the pathway is causal. The human is the cause of the divine, just as the divine is the cause of the human. Once again, and this is one of our strangest heresies, these deep complementarities are not intrinsically hierarchical.

There are other complementarities we encounter—many more—and some can be perilous waters to navigate. The female and the male are perhaps the most perilous of duals in our current cultural moment. Gender complementarity has recently been seen as a mealy-mouthed euphemism for sexism because historically one gender is subordinate to the other. I acknowledge how hard these conversations are and how much pain has been suffered by so many. With that acknowledgment in play, I believe that Restoration theology includes an importantly different way. It’s a big task, and it’s one that will require consensus within the body of Christ, including authorized ecclesiastical leaders. But there are Restoration theological resources that could support a nonhierarchical complementarity for women and men. We can see key features of that capacity in the ideology of power within the Egyptian Bible and the Nauvoo temple endowment, as two points of entry.

In the Egyptian Bible, as I detail at length in Joseph Smith’s Translation, Smith and his lieutenants were obsessed with images of female priestly power. It’s too easy in my view to be distracted by the intricacies of Abraham and Egypt and hieroglyphs and hieratic and thereby to miss the broader point. Egyptus and Katoumin and their daughters exercised intense priestly power, and they and their foremothers played key roles in the propagation of priesthood. This Egyptian Bible was a high point in Smith’s ongoing translation of the Bible. The Egyptian Bible was also the moment when he pivoted from visibly textual projects to the ritual work of the Nauvoo temple that followed. In that temple endowment, the image and substance of female priestly power intensified and expanded into a physical, ritual realm. In eternal complementarity, male and female priests would rule and reign as heavenly royals. While there are other complicated and controversial moments in the history of women and men, my point here is that the complementarity of the earliest Restoration does not require specific hierarchies for its instantiation.

I’m optimistic that the fact of complementarity is secure. There are spirit and body, heaven and earth, human and divine, male and female, among many others. I have chosen complementarity over polarity or binarity or dichotomy intentionally. I want to emphasize the promise of harmony among the partners. Even with that promise, though, the complementarities are not fully realized as such in our current phase of existence. The distance between promise and reality points to the vital and painful fact of exile.

EXILE

As my now-late Kate was wont to say, echoing the poet Geoffrey Hill, “we live in a fallen world.” I think about that phrase constantly. No matter how we sacralize the world, and we should, it is fallen and imperfect, not how we wish it to be. We are not living in the unmediated presence of God. We just aren’t. We live in exile. That is true, and it is painful.

This exile isn’t just a general sense of a world marked by death and decay, although that is true and frightening. Even if we had an indefinite lifespan, we do not currently live in heaven. It’s not just a question of our cosmic address; it’s also an awareness that we are limited in our ability to know, to communicate, to love. I, along with so many others, have experienced the heartache of absence, alienation, and miscommunication.

The experience of exile is so ubiquitous that it’s easy to emphasize at the expense of all else. It’s easy to imagine that the complementarities are permanently ruptured. There is no true meeting of people across the chasm of Otherness. There is no direct access to heaven from earth. There is an insuperable chasm between men and women. Alienation is human nature. It’s an irreducible fact. Substantial theories and disciplines have been built up around these ideas, and they gain traction from the ubiquity of the human experience of alienation.

One key touchstone of our alienation is language in all its glorious limitations. I am little surprised by the linguistic turn of the twentieth century. Those philosophers were not the first to puzzle over the nature of language, communication, and representation, and they won’t be the last. They joined, and changed, long philosophical histories in which Joseph Smith also participated with great enthusiasm and intelligence.

FAILINGS OF HUMAN LANGUAGE

I won’t spend too long reciting this history. Joseph Smith famously described human language as a “little, narrow prison” from which he struggled to break free. But he also loved to use language, to study it, to play with it, to create with it. He clearly believed, through a pure Edenic language that mediated between divine and human speech capacities, that there was suprahuman power in certain forms of language. The use of Edenic words in temple rituals and scripture, the Sample of Pure Language, the sacred word Ahman and the special valley where Adam and Ahman would come back to unity—these are all marks of the importance of a sacredly primordial language to Smith and his earliest followers.

I think that for most of us, especially scholars in the humanities, Smith’s anxieties about the limitations of language will resonate. How long have we stared at pages of crude words, how many times have we second-guessed our talks and turns of phrase, how often have we muddled through contentious faculty meetings? Language fails us, constantly. This sense of linguistic limitation is almost certainly a ubiquitous human experience.

I suspect that we will also appreciate Smith’s yearning for a better-than-human language even if we aren’t quite sure what such a language actually is. I won’t be the only one in this room who has felt the temptation of apophasis, truth that cannot be spoken, when it comes to theology. Acknowledgment of the limitations that drive us to apophasis is itself a form of yearning. Smith hoped that one day the yearning would find fruition in perfect communication. But for now we stand at least partly unspeeched in the presence of the Divine and the world with which the Divine lives in sacred intimacy. Just as the limitation of language evokes exile, so does it point toward the semantically vast notion of translation that Joseph Smith believed held the key to the return from exile. Bodies that must be prepared urgently for the presence of God require translation. The resolution of the rifts in other complementarities also require translation. Translation is what our heart calls out for.

I’m aware that I’ve been theoretical, even often abstract, to this point. And I’m sometimes in a hurry to say what’s on my mind. So I’d like to pause before doing our next bit of work together. I’ve argued that in Restoration theology, translation encompasses a variety of foundational themes. Translation mines the deep stuff that concerns us all—questions of life and death, of bemusement and bewilderment, the questions that speak to the core of us. Complementarities—what others might term dualities, binaries, polarities, or dichotomies—are a Restoration mode of thinking about the deep stuff. These complementarities are, in current human experience, marked by separation rather than unity. There are rifts in the hybrid unity of cosmos. These rifts and this separation are exile. And, crucially for the multivalent sense of the term “translation,” the specific limitations of language are a clear path into thinking about exile and alienation. But the Restoration is not just defining problems, it is also offering possible solutions. There is in the Restoration a relentless yearning for complementarities to be made whole. And this recovery of hybrid unity occurs through translation. That, in a nutshell, is what I’m wanting to say.

This account has the advantage that I believe it to be true. But I think it’s fair to ask whether I’m doing something other than just restating familiar concepts in new terms. What, in other words, do we do with this theology of translation? At a practical level, I believe that the theology of Restoration translation transforms our understanding of scripture.

THE LIFE OF SCRIPTURE

What matters on my account of translation is the extent to which scriptures translate us and we translate them in turn. Joseph Smith led the way with his never-ending translation of the Bible. On my reading, all Restoration scriptures are, among other things, translations of the King James Bible. While Bible translation is the fundamental form of Restoration scriptures, the use to which that form is put is to support human translation with linguistic translation.

Let’s start with the Book of Mormon or the Egyptian Bible. There is in them a complementarity of the living and the dead, brought into hybrid unity. The voices of the dead whisper from the dust through the pages of the Book of Mormon. Through a prismatic wormhole, Moroni sees modern readers, and we modern readers see him back. Why does the Book of Mormon obsess so much about the living and the dead being not just intelligible to each other but visible to each other? It’s because the Book of Mormon is a translation in the Restoration sense. Not just capturing words and sentences or even paragraphs, but overcoming the rift in the complementarity of the living and the dead.

Why is there so much King James Bible in the Book of Mormon? Because the textual remnants of the dead must join with the living. I’ve argued elsewhere that the Book of Mormon saves the Bible by killing it. It’s the jolt that was needed to steal the live scripture away from the Protestants who had held it for several centuries. The same, in a slightly modulated key, is true of the Book of Abraham, the Book of Moses, and even the Doctrine and Covenants.

These translation realities have something to say about certain traditional methods of reading scripture. Squabbling over proof texts as if we were fundamentalists—whether secular or religious doesn’t seem to make much difference from what I can see—isn’t true to scripture. Because scripture needs to be translating us as much as we are translating it. Scripture is not inert words or pithy summaries or evidences within a mathematical proof. Scripture understood within a Restoration theology of translation is an encounter, a melding of exiled complementarities. I recall here our own George Handley’s keen warning of the risks of reading scripture. Those risks are the possibility that we will be translated in the encounter. And we need to bear that risk. Our souls need it, our bodies need it.

Those of you of the right age may sense that I draw some inspiration from the Romanian scholar-mystic, Mircea Eliade’s, ideas about homo religiosus, illud tempus, and the irruption of the sacred into the profane. My first essay in Mormon Studies, back in 2006, was deeply indebted to that framework, and while I’ve appreciated J.Z. Smith’s and others’ criticisms of Eliade over the ensuing years, I continue to believe that Eliade captured, without intending to, the primordialist dream of the Restoration. We exiled believers yearn for the time and place where and when time and place no longer imprison us. Translation is the work of breaking out of that prison.

As one practical example, my proposed framework of translation provides context among believers for Jared Hickman’s rendition of the Book of Mormon as an Amerindian Apocalypse. Hickman’s magisterial essay suggests, among other things, that the racism in the Book of Mormon is real and illuminating as we consider Nephi as an unreliable narrator. By treating Nephi as a human character with flaws and blind spots, we readers of the Book of Mormon can see more of the plight of the modern American Native and the suffering of the peoples of Laman and Lemuel. Hickman is writing within the discipline of literary criticism, but he is squarely in the center of a Restoration theology of translation. As long as the person we call Nephi actually lived, flawed ancient prophets are in the warp and woof of Restoration scripture. We are called into communion with Nephi. As he shares with us, we learn and hopefully we share back with him. As we work better at the universal principles of love and belonging, we are being true to the ancients, lifting them as they lift us. They will see through our blind spots and we will see through theirs, and we will bring each other to life in the presence of Eternity.

The Restoration theology of translation also speaks to other modern philosophical questions. It doesn’t take long in reading contemporary philosophy of mind to learn that Cartesian dualism is dead, while embedded, embodied cognition is the new way of talking about how minds work. This can be taken to silly extremes, like Richard Dawkins’s memes or breathless recitations of behavioral psychology studies of heuristics and irrationality at cocktail parties. But in its essence, the statement is that what we call thinking is something that we do with minds and bodies. There’s a fine point here that some call out nervously. Since brains are the core and necessary substrate of minds as we know them, it’s easy to endorse embodied cognition without believing that we think with anything other than our brains. But of course, we think with other parts of our bodies. Pain, hunger, arousal, warmth, bodily position, and dozens of other stimuli and states also help to shape our thinking. What a Restoration theology of translation requires, though, is that we acknowledge not just the embodiment of cognition but also its embedment. Not just embedment in circulating cognitive constraints (what Dawkins is almost pointing toward in his clumsy analogy to genes), but embedment in community, love, and relation. We think, and we worship, in community. And scripture is a core locus of that communal cognition. There are trivial senses in which this is true, both secular and religious in common contemporary terminology. But there are deep senses in which our ability to think, feel, and worship together as a body of Saints living and dead is crucial to what we call salvation and exaltation.

The classic line from Nephi’s translation of Isaiah in 1 Nephi 19 takes on a new tenor in the setting of a Restoration theology of translation—he “did liken all scriptures unto us, that it might be for our profit and learning.” Likening the scriptures is not just thinking about their relevance in the modern setting or constructing object lessons from stray verses. It is about entering into relation with the people whose lives are contained and retold within their pages. This broader and deeper sense of likening is another view on translation.

Some of you may wonder—and some of those who have read my scholarship on these questions have already wondered—whether I am proposing an elaborate dodge. In other words, now that the Interwebs have decided that Smith’s scriptural translations do not appear to have been scholarly translations in any traditional sense, I have begun to work some legerdemain, pretending that the old questions are just category errors. In other words, we faithful few have lost the game and so changed the rules because we can’t bear to lose. Or, if we prefer a more scholarly-sounding framing of the same criticism, we Mormons are hard at work to reduce our cognitive dissonance. We are the Millerites after the Great Disappointment, looking for new predictions of the Millennium or new ways to interpret William Miller’s obviously incorrect timetables for the return of Christ.

I don’t believe this criticism. I happen to think it’s puffy nonsense. But we should engage it anyway. Honest and earnest engagement is a path to greater understanding. Not least because many Latter-day Saints have held to a strictly linguistic view of scripture and translation. Because of that history, what I am proposing may in fact represent a change in thinking for at least some Latter-day Saints. And for a particular strain of Latter-day Saint thinking, a move beyond literalism may well feel like a Great Disappointment.

I want to include a disclaimer here: I affirm the literal veracity of Restoration scripture. I am not offended or embarrassed by efforts to find Hebrew or Egyptian parallels or to map the Arabian Peninsula. I love the curiosity and engagement and seriousness manifested in these activities. I just don’t think modernist literality makes the list of the top five attributes of scripture in the Restoration. I worry too at times that we risk adopting a scriptural fundamentalism that is in its essence idolatrous. Scripture is alive, yes, but it’s alive with God and the dead and with us as readers benefiting from and engaging with translation. Scripture must not become an idol. We are truest to the Restoration legacy, I believe, when we encounter God and the ancients within Scripture, and when they encounter us. Scripture as text is the scaffolding for the translating dance of complementarity.

I’m aware that this can be taken too far into the spirit side of the complementarity between spirit and letter—even to frank mysticism—and I want to defend against that. I’m suggesting a modulation, a course correction. To polarize and then occupy one pole is to miss the point of Restoration complementarity. So we want the enfleshed bones of scripture as well as its breathing soul. That is what I’m hoping we can achieve with a deeper theology of translation.

I’m mindful that I’ve said a lot and that words are time-bound tokens of grander aspirations. I want to wrap up this entry into the endless conversation about existence with a summary of sorts. I remember again Alejandro, the Spanish tourist who died on that Russian train. I remember the feel of his dead body under my hands, the massive grief of his wife and son, the Babel of languages colliding in my head as I tried to be of use to them. I remember my own intermittent loneliness and bewilderment in that strange land, so small compared to theirs.

And I think of the vast splendor of the Restoration. There is so much wonderful work to do in making sense of the world and with the world as we are buoyed up by the revelatory grandeur of this Restoration that enlivens us. And with that grand rhetoric comes the core argument. Translation is much more than words, it is the healing of fractured complementarities, the return from exile. Translation, understood from the perspective of the early Restoration, liberates us from the idolatry of fundamentalist literalism. In so doing, it draws us into the frightening transformation that will exalt us.

This essay was originally delivered at the Mormon Scholars in the Humanities 2023 Annual Conference at Utah State University on 26 May 2023.

Samuel Brown is a physician scientist working on sepsis and ARDS. Outside medicine, he writes books on intellectual history and theology.

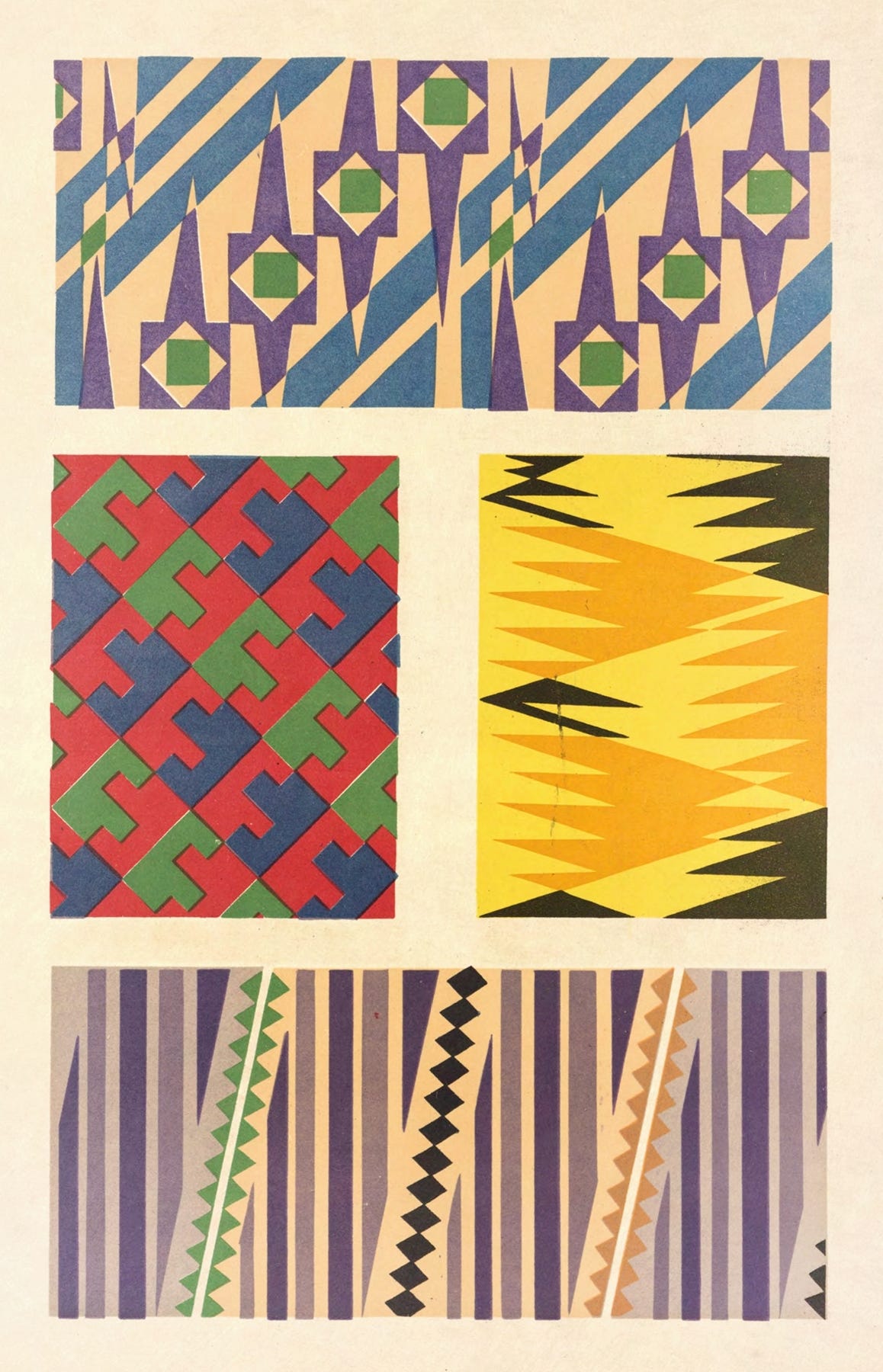

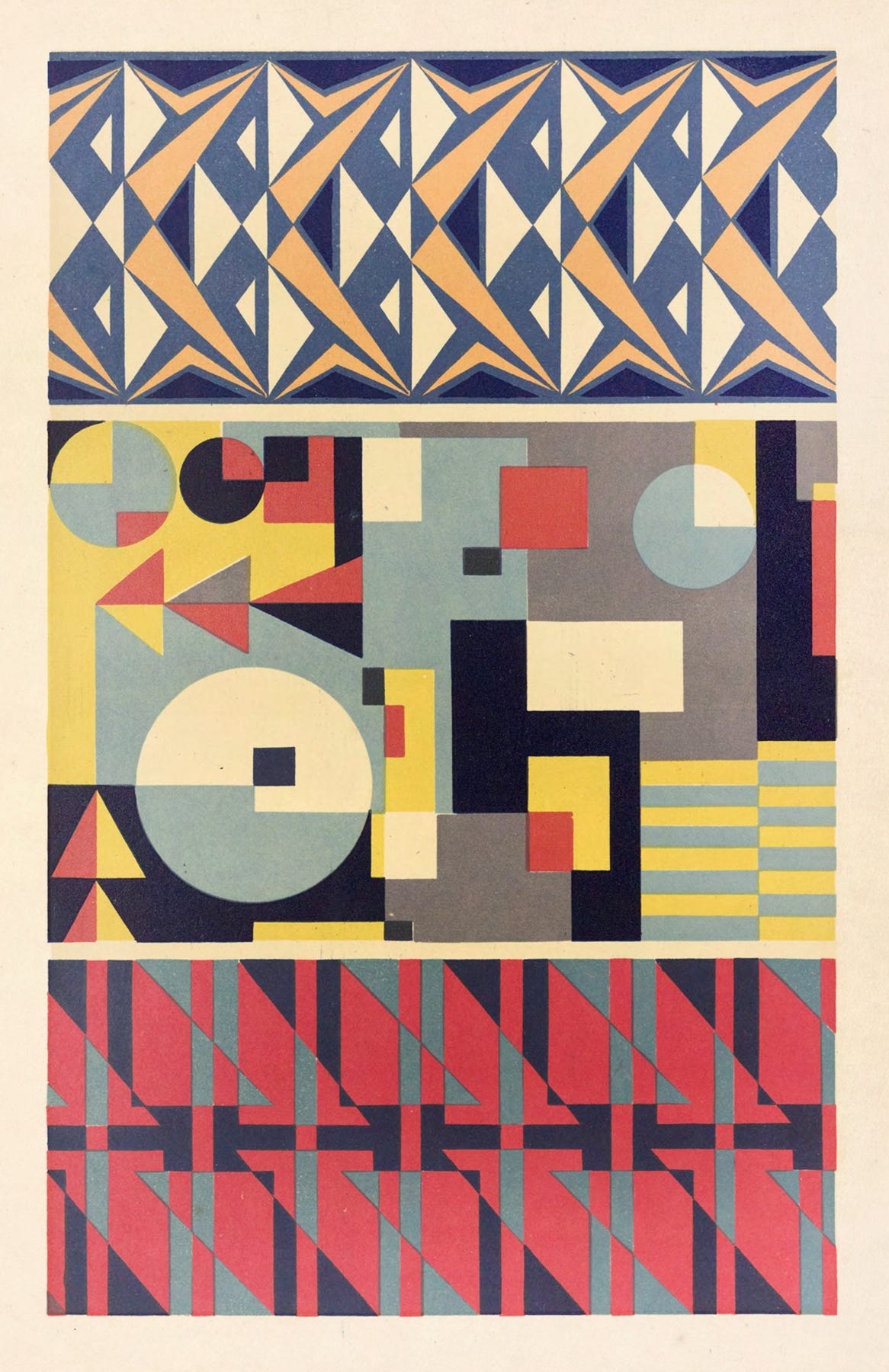

Artwork by Mizuki Heitaro.