The Theology of a Migrant Woman

Three Stories of Divine Accompaniment

Migration is in our Latter-day Saint genes. It is inherent in our culture, our families, our celebrations, our sacred texts, our rituals, and our history. We are all migrants, on a mortal journey back to God.

Since we live in a time when there are more migrants and refugees than at any point in human history, it is important to consider migration through the lens of theology. Catholic priest Daniel Groody defines theology as “faith seeking understanding that generates knowledge born of love.” How do we seek knowledge born of love as we consider the plight of current-day migrants? What new patterns of thought arise as we view this pressing social problem of the modern world through a gospel lens? Perhaps most importantly, what is our covenant responsibility in a debate that often diminishes and dehumanizes those forcibly displaced? These are questions to explore as we search for wisdom and discernment.

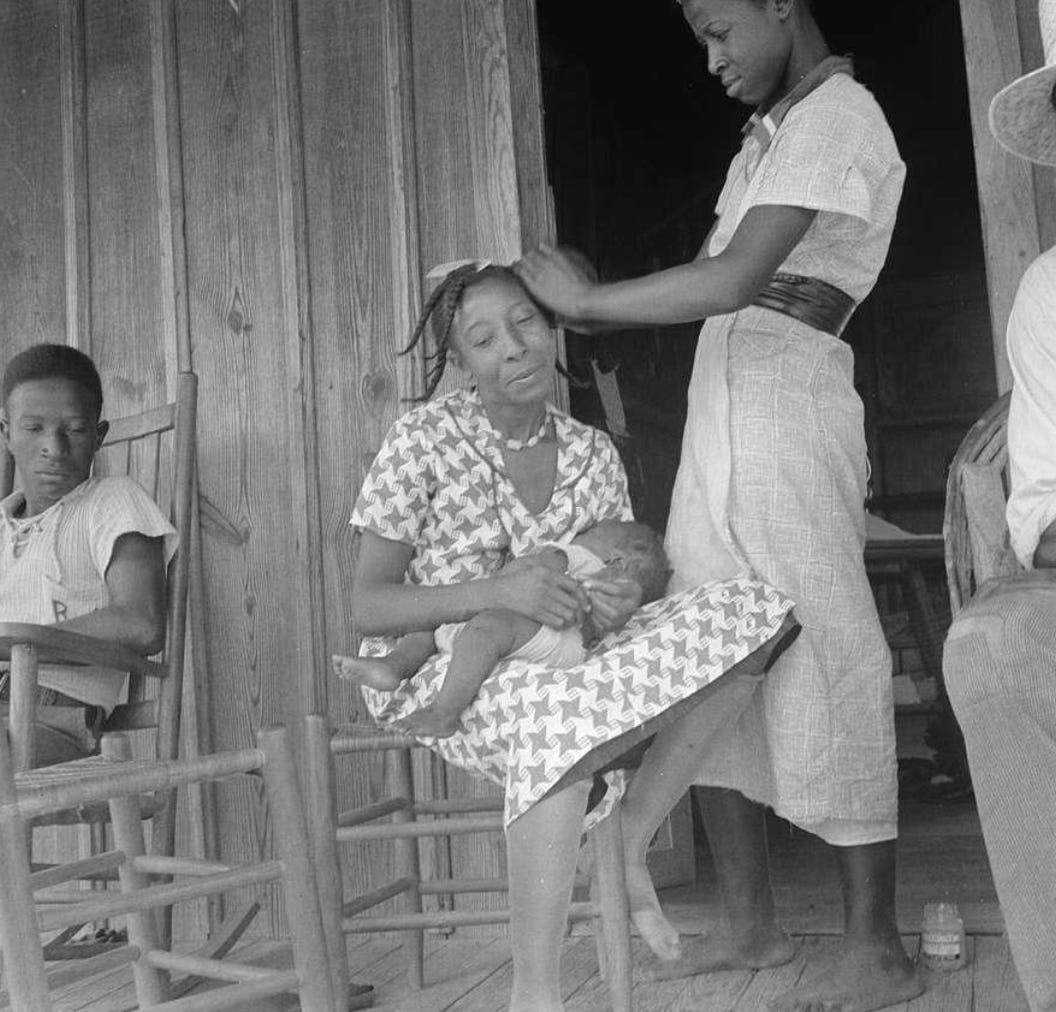

A theology of migration is not complete without considering the experience of migrant women, whose voices and perspectives are so often invisible. Fatimah Sellah and Margaret Olsen Hemming write:

Any time a group of people move from one land to another with uncertainty and danger, women will bear the brunt of that affliction with their bodies. They will bring forth life in the midst of turmoil and hardship. The refugee experience is exponentially harder for women because of what their bodies go through. They have to travel the same distance, eat the same food, sleep in the same harsh conditions, and do it through menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth, nursing, and childcare.

In order to explore the issue of migration from a theological lens, we journey now into the inner landscapes of three migrant women: Sariah the mother of Nephi, Emma Smith, and a woman we’ll call Gabriela who is currently living in a shelter on the Southern US border. Though their circumstances are vastly different in time and place, the experience of each reveals the breathtaking resiliency of the human person and the “gratuitous presence of the Spirit, erupting in places that most of the world has turned away from.” The stories they tell us about themselves and about God provoke us with self-confrontation, spurring us to ask, as did former Relief Society General President Linda K. Burton, “What if [her] story were my story?”

Sariah: “Now I know of a surety”

The account of Nephi and his family’s journey as migrants is entirely narrated from the male perspective. However, as modern-day readers and disciples, if we imagine and expand the female experience of the narrative, it is arguably just as vast and varied. Without the voices of women, we are left with an incomplete understanding of the full experience of this migrant journey. What would it be like to have a firsthand account of even one of these women who gave birth in the wilderness? The reference to the realities of the women on their journey is limited to the fact that they endured “terrible hardships” (1 Ne. 17:20). Their silence in the text is itself a form of suffering, and one that we as disciplined readers are bound to acknowledge.

Sariah, the mother of Nephi, is one of three women who are named in the Book of Mormon. It is a rare gift to have seven verses of scripture through which we are given a window into Sariah’s perspective as a mother, a wife, and a migrant woman. These verses are often seen through modern-day eyes as a less-than-faithful series of complaints, but our understanding shifts when we examine this interpretation through a closer reading. Sariah’s journey is one of deep faith in God amidst incredible sacrifice and difficulty.

Consider her losses and imagine her sorrow. She has left her homeland, her “whole sense of self, and her people.” Sariah’s loss represents real and vulnerable suffering, which should not be seen as unfaithful. Additionally, she has just sent her sons back to Jerusalem to retrieve the brass plates from Laban. Imagine the intense emotional turmoil surrounding the safety of her children in light of their dangerous mission and the long silence of their absence. Panic, tears, and sleepless nights of worry surely plague her as she mourns the possibility that her sons might have died.

As the days pass with no word, Sariah’s anxiety becomes existential. She questions the wisdom of her husband’s vision that has led to this dramatic exodus. In her distress, Sariah laments the hardship of their migrant circumstances and assigns blame to Lehi. She experiences the visceral disorientation and agony that accompanies a loss of hope, culminating in words of despair: “Behold, thou hast led us forth from the land of our inheritance, and my sons are no more, and we perish in the wilderness” (1 Ne. 5:2).

We bear witness to Sariah’s wrestle and her doubt. With reverence, we behold the raw, anguishing and vulnerable experience of a woman who is on a journey with God. And if we are willing to zoom out, we see that Sariah’s experience bears striking theological similarities to the wrestle of Jacob, who became Israel. Traditionally understood to mean “one who wrestles with God,” Israel is often seen as a symbol of those who experience a deep, personal confrontation with faith, identity, and divine purpose.

When Nephi and his brothers return safely with the brass plates, Sariah’s initial doubt gives way to testimony, much like Israel’s eventual blessing after the wrestle with God. In an expression of renewed confidence, Sariah affirms that God provided her sons “power whereby they could accomplish the thing which the Lord hath commanded them” (1 Ne. 5:2). Her faith in God is exquisitely expressed in a final soliloquy, where she “takes center stage” and states, “Now I know of a surety that the Lord hath commanded my husband to flee into the wilderness; yea, and I also know of a surety that the Lord hath protected my sons, and delivered them out of the hands of Laban” (1 Ne. 5:8).

We have no record of Sariah having visions or angelic visitations like the men in her family. Instead, she must learn to trust, to reach, and to persevere without cosmic encounters. She, like most of us, sees “through a glass, darkly” (1 Cor. 13:12). In this glimpse into Sariah’s story, we witness and honor her joy and faith intertwined with sorrow and hardship. Her inner migratory journey is marked by struggle, doubt, and growth as she presses forward with faith in Jesus Christ, the great Liberator.

Emma Smith: “I feel a divine trust in God, that all things shall work for good”

While there are three women named in the Book of Mormon, only two women are mentioned by name in the Doctrine and Covenants. One of these women is Emma Hale Smith, the first wife of the prophet Joseph Smith. Emma plays a key role in the early days of the Church, supporting Joseph during the translation of the Book of Mormon and enduring continual, lifelong persecution both inside and outside the faith.

Much like Sariah, Emma’s complex experience—including her decision not to join the Saints in their migration to Utah after Joseph Smith’s martyrdom, and her strong opposition to polygamy—has been viewed by some as problematic and unfaithful. We must be diligent in remembering that many of the interpretations of Emma and her choices come through the lens of the male authorities around her, including revelation conveyed through intermediaries. To examine and consider the lived reality of Emma herself is necessary to understand the theology of this faithful migrant woman.

Emma’s journey, like Sariah’s, is marked by both resilience and sacrifice. She seeks, writes, speaks, and stands with determined, courageous poise. She faces the prolonged trauma of poverty, displacement, and threats of angry, violent mobs as she and her family migrate first to Kirtland, Ohio, then to Missouri, and finally to Nauvoo. Along the journey, Emma endures excruciating hardships, including the death of several children and the harrowing wrestle with her husband’s practice of polygamy, which ultimately led to his imprisonment. The death of Joseph on June 27, 1844, is unbearable for Emma—for in addition to grieving his violent murder, she is expecting their final child. Linda King Newell and Valerie Tippets Avery, Emma’s biographers, shed light on the agony of this unimaginable experience:

Unassisted, she walked to Joseph, where she kneeled down, clasped him around his face, and sank upon his body. Suddenly her grief found vent, and sighs and groans and words and lamentations filled the room. Her children, four in number, gathered around their weeping mother and the dead body of a murdered father, and grief that words cannot embody seemed to overwhelm the whole group.1

In this culminating moment of terror and paralysis, the question of how life could continue surely afflicts Emma. Perhaps this is one of the moments that she is reflecting on when, at age sixty-two, she writes, “How often I have been made deeply sensible that my pilgrimage has been an arduous one and God only knows how often my heart has almost sunk.”2 Amidst seasons devoid of hope, Emma finds solace in God, whom she acknowledges as the One who knows her.

We honor Emma’s courage. She is an example of a woman who creates a new future, working towards wholeness and healing even when her world seems to have been utterly destroyed. As she learns to trust her own intuition in the journey through her difficult life, she never loses her faith in a loving God. In her final years, Emma offers us a glimpse into the inner landscape of her theology as she tenderly testifies to her son:

Joseph, I have seen many, yes very many trying scenes in my life in which I could not see any good in them, neither could I see any place where any good could grow out of them, but yet I feel a divine trust in God, that all things shall work for good, perhaps not to me, but it may be to someone else.3

Through our brief glimpses of these two migrant women, perhaps the most poignant theology that emerges is that God’s promises are not always tied to outcomes. Both women ultimately experience tremendous loss: Sariah in the fracturing of her family that leads to generations of hostility and enmity, and Emma in cognitive dissonance that results in her painful but courageous decision to remain in Nauvoo rather than continuing west with the Saints—a decision that continues to misrepresent her as a problematic figure. Sariah’s and Emma’s experiences reflect the theological idea that God is not distant, but intimately present, accompanying those who are displaced, rejected, marginalized, and oppressed.

Gabriela: “I must continue to hope”

On a border pilgrimage in late January 2025, I traveled to Mexico with a group of fellow theology students. In a border shelter, I met Gabriela, who was quiet and distressed. She had just been told that her path towards legal immigration into the United States had dissolved. I learned that Gabriela was forced to leave her homeland due to violence and government instability. She had been on the move for several months, arriving here in the border shelter as a temporary accommodation while anticipating legal entrance into the US. Her failed path forward mirrored the obliterated path upon which she had travelled. Gabriela couldn’t return home. She had lost contact with her two oldest teenage children, without hope of reconnection. Bewildering pain cratered her countenance. I wondered whether it would be better to offer her solidarity through silent presence or compassion through listening and validation. I gently touched her shoulder; she responded with a sob.

With the help of Google Translate, a tender conversation unfolded. “What gives you hope?” I asked. “God,” she replied simply, with emotion. “My faith in God. I don’t know what is going to happen to me, to my children, to my life . . . but I know that Jesus Christ walks with me. I must continue to hope.” I reverently honored her faith and her courage, fighting back tears. I will never forget leaving the shelter, turning back one last time, and seeing Gabriela and her daughter watching me, their hands forming hearts.

In Gabriela’s unfinished story, Jesus Christ represents companionship, respite, and relief. He knows what it means to suffer, to be abandoned, and to be dehumanized—just as she has been. She clings to the knowledge that Jesus faced the darkest parts of the world, but was not overcome by them. Gabriela’s theology views the resurrection of Jesus Christ as a firm rejection of the destructive systems—social, political, economic, and religious—that harm the vulnerable. Jesus Christ accompanies her in her suffering, and her hope lies in the affirmation that those who the world deems worthless are cherished as beloved children of the Living God.

What Is Ours to Do?

The theologies of Sariah, Emma Smith, and Gabriela bear a similar, universal message: that God is a God of accompaniment—a God who walks with us, who shares our burdens, who is present in our suffering, and who leads us to hope—through the journey of migration. Theirs is an experiential soteriology; an encounter with Christ from the margins that narrates a holistic experience of salvation in the midst of uncertainty, fear and trembling. Salvation is hope of liberation, yes—but “in liminal spaces of survival, salvation is also an embodied event that responds to the daily suffering of forgotten people.”4

From this perspective, a sobering question emerges: How can we speak of and seek heavenly rewards and exaltation with such passion and zeal when faced with the reality of so many whose lives are disordered and upended through violence, abuse, poverty, and displacement? How can we place so much emphasis on the forgiveness of sin through the Atonement of Jesus Christ while being complicit with social and economic policies that cause acute suffering to the migrant and the poor? How can we sleep peacefully despite the millions around us who suffer in the world? Any theology that does not incorporate a radical call to serve those at the margins is, in Dietrich Bonnhoefer’s words, “cheap grace.”

Sariah, Emma, and Gabriela’s stories call us into the migrant experience—to enter into the spaces of pain, doubt, loss, and human vulnerability and to confront what we would rather avoid, with as much courage as we can muster. Their stories challenge us to consider that only a theology of the privileged can ignore God’s call to move outside of our self-constructed borders. Salvation is not just about personal righteousness, but about healing whole communities of people whose knees are feeble and whose hands hang down. “Salvation does not begin at the centers of power, which are blind to their inherent sin of injustice. To truly experience God’s salvation, one must begin at the periphery, where Jesus beckons us to follow.”

For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in. I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.

May we be willing to heed His call.

Jenny Richards recently received her Masters of Theological Studies degree from the Franciscan School of Theology at the University of San Diego. She will begin a chaplain residency in Salt Lake City in fall 2025. You can find Jenny’s musings at @walkingtheroadtojericho.

Photography by Dorothea Lange (1895–1965)

B.W. Richmond’s statement, “The Prophet’s Death!” Deseret News, 27 November 1875, reprinted from the Chicago Times, as cited in Mormon Enigma, 197.

Emma Smith Bidamon to Joseph Smith III, 19 Aug. 1866, RLDS Library and Archives.

Emma Smith Bidamon to Joseph Smith III, 17 [no month] 1869, RLDS Library and Archives.

Martell-Otero, “From Satas to Saints—Sobrajas No More: Salvation in the Space of the Everyday,” in The Strength of Her Witness, ed. Elizabeth Johnson (Orbis Books, 2016), 240.

Excellent essay. This resonates deeply right now.