The Re-Enchantment of the Earth

An Outline for a Restoration Eco-Theology

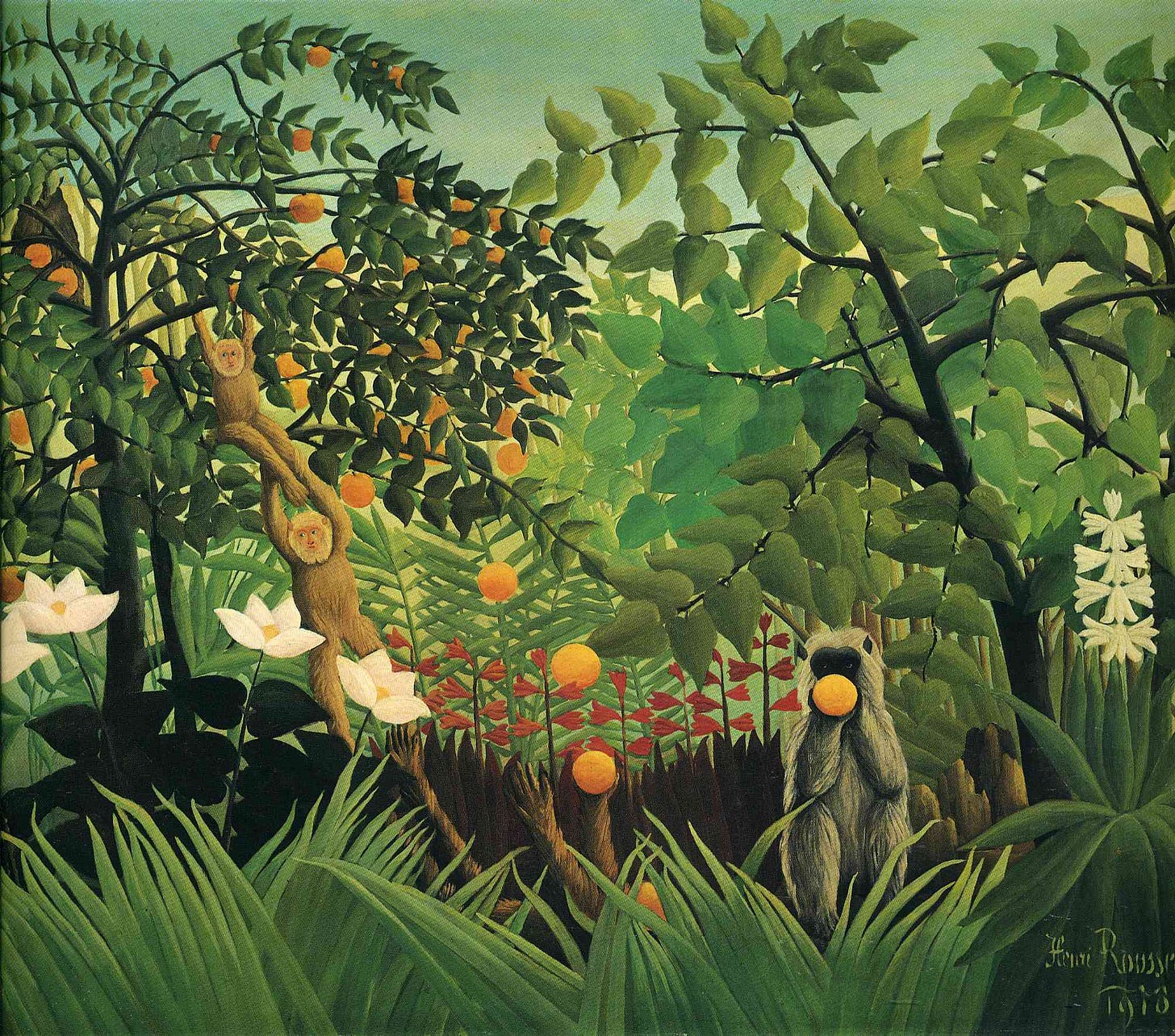

There is a well-defined but little-recognized eco-theology at the heart of the Restoration, as laid out by Joseph Smith and his early followers, that puts humanity at the same level as every other creature on this earth: All life and landscapes are endowed with a spiritual essence of one form or another. The earth and all its flora and fauna form a “great community” that includes humans and everything from baboons to bacteria and even fields and floods, rocks, hills, and plains. Our eyes are opened to an enchanted world when we recognize the "aliveness" of all that is around us. I argue that a sense of enchantment is at the core of what we might imagine for a Restoration Eco-theology.

What Manner of Creation?

The Restoration concept of the creation lays the groundwork for a unique environmental ethos that combines a deep spirituality and reverence with a pragmatic scientific approach.

In contrast to a creatio ex-nihilo or creation out of nothing espoused by most of Christianity, the Restoration posits a creatio ex materia, or an organizing or reframing of existing material. But importantly, the Restoration does not posit an all-powerful God who just makes things up out of whole cloth. Rather, all matter, as well as God, is bound by the laws of nature. E=mc2 is not an arbitrary relationship. It is a law of nature inherent to matter in the universe.

What this means, at least to a scientist, is that when we study nature, we are studying the warp and woof of nature itself, whether that be a soil food web or the formation of vast nebulae millions of light years away. It is not so much, then, that we are studying God’s handiwork; we are, rather, looking at the natural workings of the universe. And our Heavenly Mother and Father are part of those natural workings. The earth and life on it continue to evolve. Nature has its way, and every valley is eventually exalted, and the rough places made plain. The water cycle, the nitrogen cycle, the rock cycle, and indeed all cycles carry on without divine intervention.

But the Restoration does posit some form of divine intervention in the workings of this planet. Just how detailed an intervention we cannot comprehend. But we can know that our heavenly parents intend for this earth to serve as a home for their spiritual children, as well as for all life that has evolved on this planet. Anything at all, then, that reduces the capacity of this earth to provide for life is a desecration of the Lords’ purposes. If topsoil is eroded away, that means less fertility and a reduced carrying capacity of the Earth. If rivers and lakes are polluted, less life can be supported. It is not just the carrying capacity of humans that are of divine concern. All life must be supported. All life can only be supported if sufficient habitat is provided for each life form. Ecological integrity must thus be maintained, which means that preserving only small patches of particular biomes is not sufficient to maintain coherent biotic communities.

Enchanted Rocks

The Restoration teaches us that matter is eternal, and that matter can neither be destroyed nor created. Brother Joseph, in fact, taught that matter really is all there is. According to Joseph, even spirit is matter, just a much more refined kind of matter.1 But Brigham Young took it yet one step further, by declaring that all matter in one form or another is endowed with this refined matter or spirit. We are told, for example, that trees have spirits, as do all plants and even rocks.2

Our planet, and all that is on it, then, is in some sense alive. We thus live and walk on an enchanted landscape. We might even say it is a magic world that we live in. A magic borne not of superstition but of awe. What is magic but that which we do not understand? How well do we think we really understand the workings of our planet, much less the universe? Wilford Gardner, a twentieth-century soil scientist with deep Mormon roots, once said that not only is soil more complex than we imagine to be, it is more complex than we can imagine it to be.3 That is an awe borne of a humility that recognizes just how feeble our ability is to understand nature. And he was talking about soil, that seemingly most mundane component of the landscape, that which the uninspired might refer to as dirt.

So what, then, is enchantment, exactly?

Thomas Moore tells us that "once we allow the world itself to have a soul and an interior life, then enchantment begins to stir."4 The idea that rocks and trees, etc., have some kind of spiritual dimension is indeed enchanting. This is a concept that Brigham did not spin out much beyond his initial enunciation of the idea. But it is a rich concept that could help elucidate just what a loving relationship with the earth might look like.

The relationship with the earth is what is critical. It is not enough to simply study the workings of nature. Alister McGrath points out that "research in the natural sciences often seem[s] to be little more than a prelude to exploitation of nature, so that the study of nature all too often [leads] directly to the pillage of nature."5 This is where an enchanted perspective could help steer research away from plunder and towards sustainability. What we might call a Restorationist perspective.

Now it is not my intention to weave a complete tapestry of a Restorationist eco-theology. It is, rather, to engender further dialogue on these uniquely Restorationist concepts. And perhaps more importantly, my intention is to place these concepts squarely in the center of Restoration principles, such that no one choosing a career in the environment would ever think that they were somehow on the fringe of the Restoration. And that leaders and members in general would not be surprised to find their church way out in front on environmental issues.

Enchantment is a bit elusive in terms of definition. But a fuzzy definition might be better than a narrow definition. The fuzzier the definition, the easier it is to tease out any number of layers. I have already used here various concepts that could be synonyms of or at least closely related to enchantment. For example: awe and a sacred earth.

The etymology of enchantment has an element of singing and perhaps even rhythm. En-CHANT-ment, signifying chants, or in Spanish En-CANTO—singing. A beautiful passage by Wendell Berry, a prophet of the environment if there ever was one, is a powerful expression of a song of enchantment:

If we are to protect the world's multitude of places and creatures, then we must know them, not just conceptually but imaginatively as well. They must be pictured in mind and in memory; they must be known with affection, "by heart," so that in the seeing or remembering them the heart may be said to sing, to make a music peculiar to its recognition of each particular place or creature that it knows well.6

There are thus many angles from which to define enchantment. Life, the web of life, and our placement in this universal web speaks most strongly to me of enchantment.

Now, many of the people I am citing are not LDS. So what is uniquely Restorationist about the ideas examined thus far? I believe it is the weaving together of these ideas that can be illuminating. But the idea of uncreated or eternal matter, and a spiritual (read refined matter) dimension infused through all of creation is a unique foundation on which to build.

The World in a Grain

To hold in your hand sweet, fertile soil, and to catch a glimpse of its complexity is to hold infinity, said William Blake. The poet sees what the scientist cannot—the world in a grain, and heaven in a wildflower. But even the most rigorous scientist with each probing will open new doors and find new mysteries and will behold them with awe.

Knowing that nature is alive, and more complex and wonderful than we can ever imagine it to be, endows us with a sense of awe, whether we be scientists or not. And more than awe, we are endowed with a deeper sense of enchantment the more we probe the workings of nature. This enchanted sense of awe is what should be driving scientific research. The demands of promotion and tenure likely attenuate that drive.

So what does it mean to live on an “enchanted” planet? Does it mean leprechauns are hiding in the bushes and that fairies dance around us? Not hardly! There is a big difference between awe and superstition. The Oxford English Dictionary defines awe as being in a state of reverential wonder. Superstition is holding on to meaningless and likely irrelevant concepts. The more you know what lies behind superstitions, the less superstitious you become. Awe, on the other hand, only increases the more you know about the real workings of nature.

Living Enchanted Lives - What Difference Would it Make?

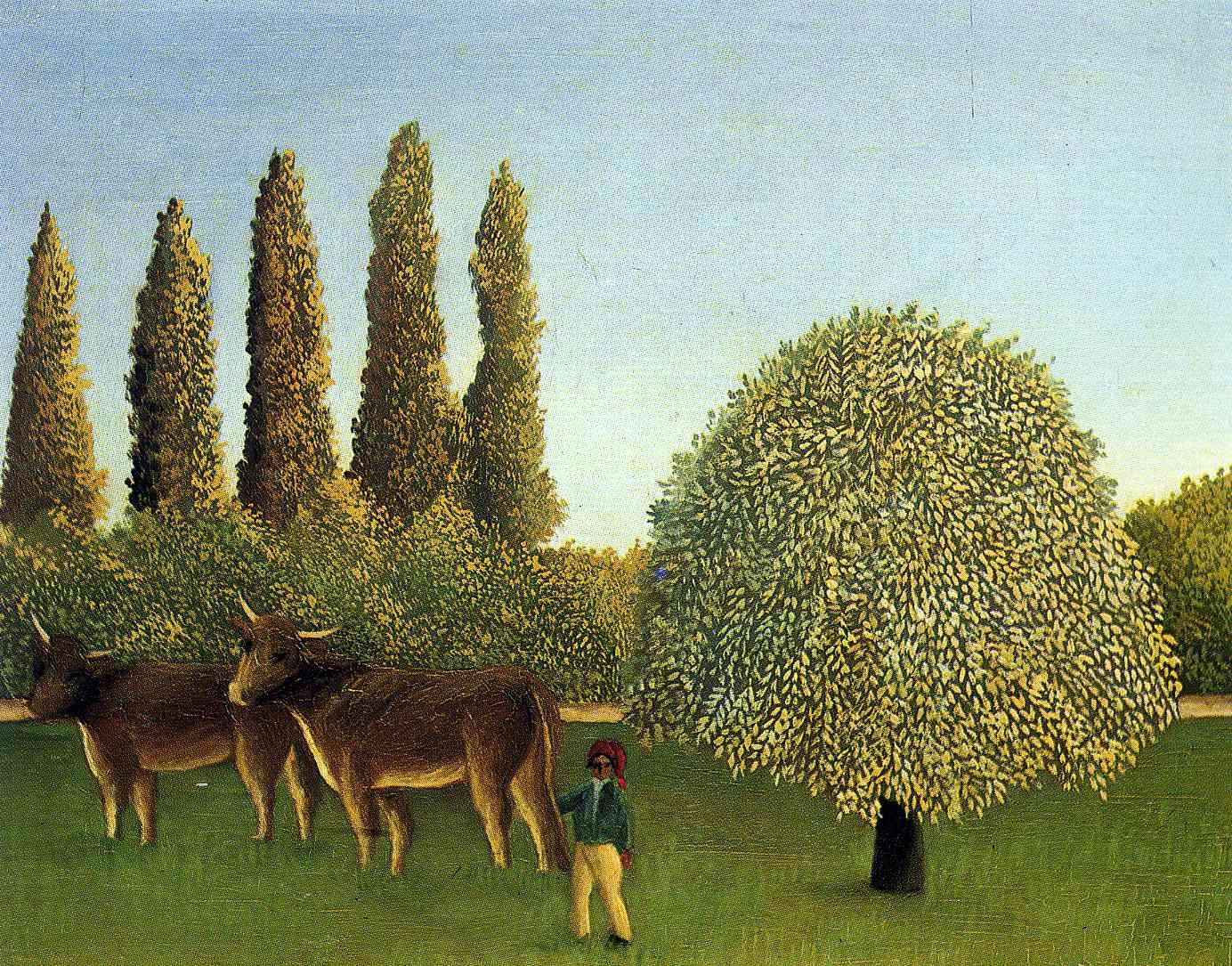

Living in an enchanted environment means it is all sacred and must be treated with care. It means that we tread lightly. It means that we take only what we need, and that we honor what we take.

Some anthropological studies have documented rituals that the Q’eqchi’ Maya in Guatemala perform when planting corn.7 Part of that ritual involves a prayer to the earth, asking forgiveness for having to cut down trees and disturb the soil to be able to plant corn. Perhaps we should be asking forgiveness ourselves for what we do to the earth. The Q’eqchi’ ask for forgiveness for what they cannot avoid doing. We ask for no forgiveness for desecrations that we most certainly can avoid. A sacred and alive landscape calls out for us to minimize our disturbance and to tread lightly.

Given that we must take from a sacred and enchanted earth, it follows that we should honor what we take from this very special planet. To honor what we take means first that we take with care. We minimize soil erosion and we ensure that creeks and rivers run clear and free of pollutants. While everything is sacred, some areas are more sacred than others, and we pay attention to the needs of those more sacred areas.

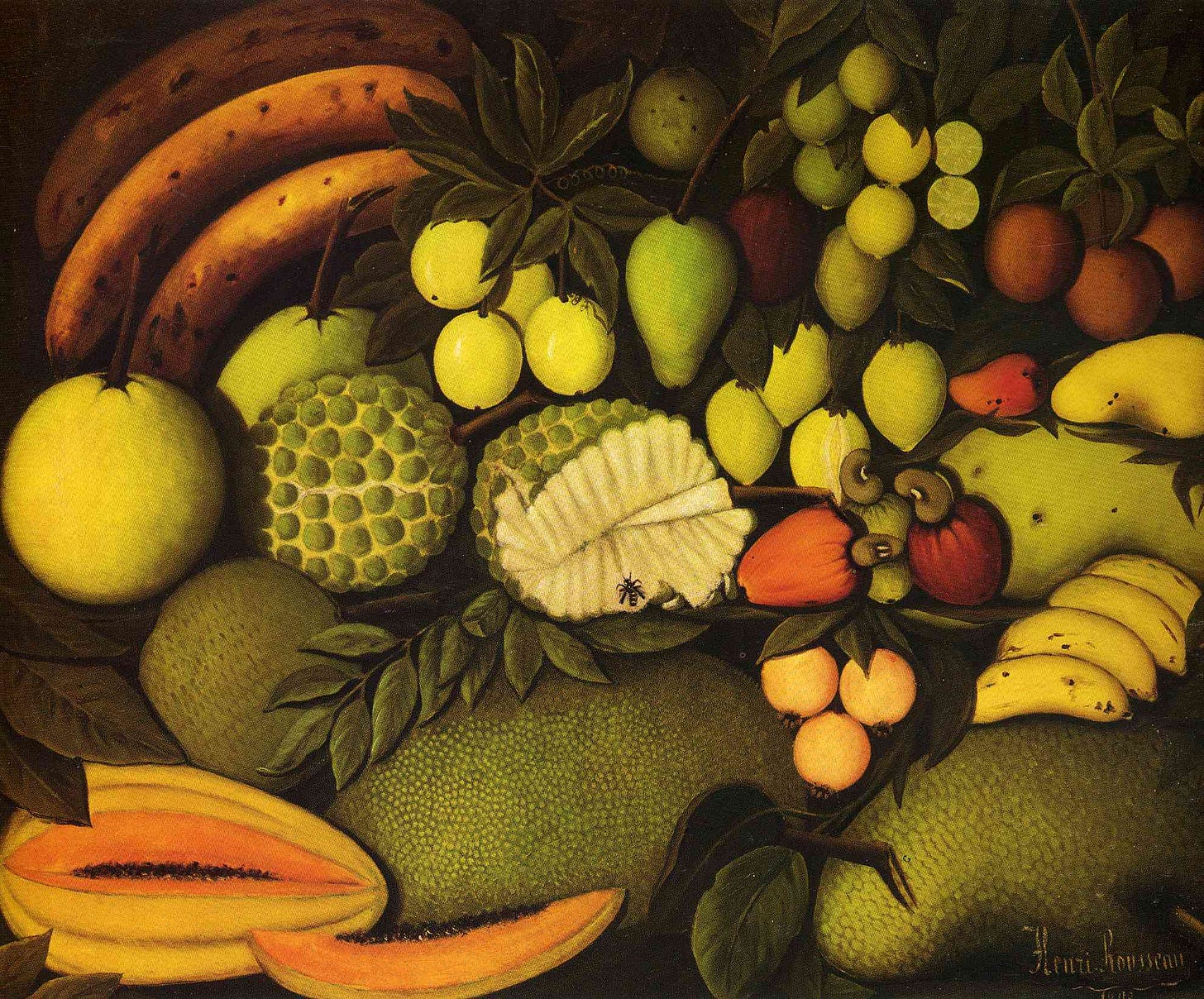

Honoring the earth that sustains us also might have something to do with producing healthy, restorative food versus low quality foods like corn chips and high-fructose corn syrup.

We must of course manage and use the land to feed ourselves and to build our cities. Here we need some guideposts to our work of sacralizing the earth. Two mid-twentieth century thinkers come to mind: Aldo Leopold and René Dubos. Leopold posited the idea of a land ethic and the health of the land as a measure of how well the land ethic was carried out.8 Dubos borrowed the term "The Wooing of the Earth"9 from Rabinidrath Tagore and expanded it into a modus vivendi. The phrase conjures up a certain gentleness in the relationship with the earth. It also conjures up an intimacy that must come into play if we are really going to woo the earth. What do we recognize about the places we live? If we live surrounded by prairie, how many grasses can we or our children recognize? Do we know the boundaries of the watershed we live in? Where are our wastewater treatment plants? That intimacy could extend to any number of areas. We can't see enchantment unless we are at least somewhat intimate with our places, and the flows that come and go through our places..

Honoring what we take extends to the built environment as well as the natural environment. We must take not only for food, but for places to live as well. Do we build places of enchantment that foster community interaction? Or do we build habitat-eating sprawl that foments isolation within gated communities? We honor what we take by building cities and towns that are durable and enchanting.

The Plat of the City of Zion should inspire us here. The Plat enthrones walkability as a key feature of urban planning. Joseph recognized that walkability engenders sociability. From the point of view of the environment, compact, walkable cities and towns pave over much less prairies, forests, and farmlands than standard development, by several orders of magnitude.10

The Restoration of Relationships – The Great Community

Near the end of his life, Joseph laid out what he viewed as the two grand fundamentals of the Restoration.11 One of the grand fundamentals was to receive truth, come from where it may. The other was friendship. Joseph declared, in fact, that friendship was the grand fundamental principle of the Restoration.

I propose expanding the grand fundamental of friendship to extend beyond humans-to-humans to amity between humans and all of creation: all flora and fauna, to include the entire biota, all rivers and lakes, watersheds, as well as soil and rocks. This would situate us in a “great community,” where we are stewards, but not merely stewards. We are of one spirit with all that there is, albeit with some special responsibilities for ensuring habitat for all. As the top predator on this planet, there is a certain noblesse oblige that comes with that position. It means, says Dubos, "that we must continue to intervene in nature, but we must do it with a sense of responsibility for the welfare of the earth."12 It is about taking the long view, and who better to do that than Latter-Day Saints, with our emphasis on long chains of relationships. Many Native Americans tell us we we must imagine the impacts of our actions on the 7th generation. A little reverse genealogy in action, as it were. Perhaps one day we might imagine a seven-generation program to match our four-generation program going the other way.

The Great Community is at the heart of an emerging Restoration eco-theology. A community informed by reverential awe. A community that asks us to be intimate with all of creation. To be intimate with nature is to know it profoundly. Just as a lover knows the quirks and caprices of their beloved, as well as their character and disposition, so too must we, as the top predator, know how to woo nature not only to our own ends but to the ends of every living thing on the earth.13 This wooing requires not only detailed scientific knowledge, but perhaps more importantly, an imagination grounded in wonder and awe. This is what real enchantment is all about.

The recognition of an enchanted earth is a natural part of any Restoration eco-theology. It is what allows us to see the beauty all around us. But the idea of an enchanted earth does not mean we can’t approach land or even planetary management with a solid scientific approach. Aldo Leopold, a prophet of sustainability and of the holy earth, suggested that achieving both utility and beauty, in other words, both science and enchantment, would lead to permanence of the places that sustain us14, which I would argue include both natural and built environments.

The Great Community that emerges when Restoration scriptures are taken seriously extends to economic, not just ecological questions. Ecology and economics describe our entire planetary household. Ecology and economics deal fundamentally with relationship: a healthy ecology cannot exist without a healthy, healing economy. And of course, a healthy economy, as described by the Restoration at least, cannot function for long without being embedded in a healthy ecology.

There are no externalities in a Restoration economy. Only full-cost accounting of all environmental costs will enable us to minimize impacts and in fact achieve net-zero contamination. By choosing full-cost accounting, we are recognizing that any costs not accounted for only reduce the carrying capacity of our planet.

There is plenty within Restoration scripture that points to an economic order that could be consistent with a Restoration eco-theology. The United Order stands out, of course, but let us consider just two Restoration scriptures that tie economic and ecological theologies together.

Section 104 of the Doctrine and Covenants suggest that the earth is full and that there is enough and to spare, in terms of resources (v17). Presumably enough to sustain the entire biota. Such a declaration today seems like pure fantasy. But the scripture asserts that the earth is not inherently full, but rather that this abundance very much depends on economic relations among Earth’s citizens. We are told that equality is what makes this abundance possible (v 17-18). Exalting the poor and laying the rich low appears to be the mechanism for establishing this equality (v16).

Furthermore, we are told in Section 59:20 of the Doctrine and Covenants that forcing the earth beyond its limits is a form of extortion, and is not something that leads to the abundance referred to in Section 104. Clearly our management of the earth, for our own interests or in the interest of the entire biota, must recognize the limits of soils and streams and rivers to sustain us and the rest of the biota.

Hidden Treasures

A study of Restoration scriptures opens the door to an enchanted view of the earth. An enchanted view that invites us to be part of a great community, and that demands of us a deeper knowledge of our earthly household, and a greater role as partners in the care of creation.

More and more people today, especially among the young, seek a more harmonious relationship with the natural world. Perhaps the new generation of Latter-day Saints uncover neglected Restoration treasures that will enable the Church to take the leadership role that it must take in terms of building a sustainable Zion (what other kind could there be?). After all, the scriptures declare that this very earth will be our celestial home. Would not an earthly celestial home be an enchanted place, whether that home be a humble single home, the entire earth, or everything in between? All we need is new eyes to see, and care for, the paradise all around us.

John Jacob is a retired Professor and Extension Specialist with the Texas A&M University System. He and his wife split their time between Guatemala and Houston.

Artwork by Henri Rousseau.

An earlier version of this essay first appeared in Wheat & Tares.

D&C 131:7-8

Journal of Discourses. Vol 3, pp. 272-279. March 23, 1856

Gardner, W.R. 1991. Soil as a basic science. Soil Science. 151:1 p2-6

Moore, Thomas. 1996. The Re-Enchantment of Everyday Life. Harper Collins. New York, NY. p 303.

McGrath, Alister. 2002. The Re-Enchantment of Nature. The Denial of Religion and the Ecological Crisis. Doubleday. New York, NY. p x.

Wendell Berry. 2001. Life is a Miracle. Counterpoint Press, New York, NY

Carter, William E. 1969. New Lands and Old Traditions. Kekchi Cultivators in the Guatemalan Lowlands. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

Leopold, Aldo. 1987. A Sand County Almanac. Oxford University Press. New York.

Dubos, René. 1980. The Wooing of the Earth, Charles Scribner's Sons. New York.

Galli, Craig. 2005. Building Zion: The Latter-day Saint Legacy of Urban Planning. Brigham Young University Studies. Vol 44 No 1. p111-136.

Bradley, Don. 2006. The Grand Fundamental Principles of Mormonism: Joseph Smith’s Unfinished Reformation. Sunstone. April 2006, 32-41

Dubos, René.

Dubos, René.

Leopold, Aldo. 1999. “The Land-health Concept and Conservation.” In For the Health of the Land, edited by J. Baird Callicott and Eric T. Freyfogle. Washington D.C.: Island Press.