The Prophet and the Priest

Joseph Smith's Ecclesiastical Roles

“If you start a church with a prophet in it everybody will be against you,” Smith’s friend W.W. Phelps wrote ruefully in 1835. People had been calling Joseph Smith a prophet since before he organized his church in April of 1830, and the revelation that he presented to the group of people there that day claimed the title. “Behold there Shall a Record be kept among you & in it thou shalt be called a seer & Translater & Prop[h]et,” it said. They voted to accept this statement as the word of God.

But soon Smith reached for another title too. In November 1831, he dictated a revelation that now comprises the latter half of the current section 107 in the Doctrine and Covenants. Several passages near the beginning of that revelation (now versus 64-66) delineate that office.

“Wherefore, it must needs be that one be appointed of the High Priesthood to preside over the priesthood, and he shall be called President of the High Priesthood of the Church; or, in other words, the Presiding High Priest over the High Priesthood of the Church.”

In January 1832, an assembly of the Church voted to sustain Joseph Smith as the President of the High Priesthood, and at that conference he was ordained the President of the High Priesthood of the Church.

This is, in fact, the formal title of the man who is in charge of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, his technical ecclesiastical office, even as the November 1831 revelation acknowledges that the Church sustained Smith as a prophet too.

In other words, Joseph Smith and his successors are presidents of the high priesthood who are also prophets. Of course, in the Church today, the word “prophet” has become the common title for the president of the church. He is referred to as “prophet” as though that is the source of authority for his presidency. For example, in the spring 2023 General Conference, Alan Haynie recalled seeing a president of the Church on television when he was young. “That’s President David O. McKay; he’s a prophet,” Haynie said.

And yet, it matters that this person’s official title refers not to prophecy, but to priesthood. The distinction is important because understanding it will help us avoid a skewed vision of what the job of the president of the Church actually is. And understanding that means that we can dodge false expectations, and grasp more fully what it means to be a member of the Church.

PROPHETS

The word “prophet” derives from the Greek, and it’s the word the authors of the New Testament used to translate the Hebrew word “nabi,” an ancient Mesopotamian term which, according to the scholar of the Hebrew Bible Marc Brettler, gestures to meanings like “the one who is called,” or “named,” or “calls out.”

The first use of the term in scripture is in Genesis 20 (KJV). There God tells the king Abimelech that Abraham is a “prophet, for he shall pray for you.” This is nice—Abraham is named a prophet because he calls out to God on behalf of someone else. But it also establishes that a prophet is a person who experiences communication with God.

A number of other figures in the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament) are also named prophets, including the traditional three major prophets, Isaiah, Ezekiel, and Jeremiah, a dozen traditional “minor” prophets like Haggai, Zechariah, and Amos, and quite a number of other people who don’t have their own books.

That list includes several women who are referred to with the word “nabi,” including Moses’s sister Miriam and Deborah, a judge in the Book of Judges. The New Testament also refers to female prophets, most prominently “Anna, a prophetess, the daughter of Phanuel, of the tribe of Aser,” who greets the infant Jesus in the second chapter of Luke.

The apostle Paul defines what it is to be a prophet in several of his letters, most famously in 1 Corinthians 12 (KJV). There Paul lists “prophecy” among a number of “spiritual gifts,” alongside “the gift of healing,” “the working of miracles,” “the interpretation of tongues” and several others. In Romans 12 (RSV) Paul says, “Having gifts that differ according to the grace given to us, let us use them. If prophecy, in proportion to our faith.” The Book of Mormon echoes Paul’s definition in Moroni 10, where Moroni explains that prophecy is “a manifestation of the Spirit of God.”

In short, scripture understands prophecy as the gift of communication with God, which God grants for divine purposes. It is not an ecclesiastical office or a superpower. Nobody is ordained a prophet.

Scripture offers a number of rather dramatic scenes in which God designates various people as prophets, including Isaiah, Ezekiel, and Lehi. The person is often stricken, like Lehi, who takes to his bed afterward, overcome by what Jeremiah (RSV) describes as “a fire burning in my heart and imprisoned in my bones.” There is no laying on of hands; rather there is a powerful experience of the divine that results in a profound awareness of God’s will.

Oftentimes, indeed, prophets are placed in opposition to established religious leadership. In chapter 7 (RSV) of the book named for him, the prophet Amos confronts the priest Amaziah, who seems to have no idea who Amos is. Amos seems rather dazed by the situation himself, and confesses “I am a herdsman, and a dresser of sycamore trees, and the Lord took me from following the flock, and the Lord said to me, Go, prophesy to my people Israel.”

Prophets, in short, may come from anywhere. In the Book of Mormon Abinadi is like Amos. He simply appears in the story and seems a complete stranger to the established leadership of his time. Samuel the Lamanite is an even greater outsider, rejected precisely because he was a Lamanite.

It’s this sort of romance, the sense of the prophet as the lone person against the system, that makes the figure of the prophet so appealing in modern America when a lot of our popular entertainment and the way we pick presidential candidates is premised on the archetype of the noble outsider.

When modern Americans use the word “prophet” today they tend to be drawing, even if unconsciously, on nineteenth-century Germans. In particular I’ll point at the academics Julius Wellhausen and Max Weber. Wellhausen is a major figure in Bible scholarship, and he was a Protestant with a good deal of anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish sentiment. He argued that the Bible shows an evolution of religion from what he thought was primitive ritual (animal sacrifices, priestly classes, ritual clothing) to modern religion, which he said had to do with cultivating personal faith and living a good life. For Wellhausen, the prophets had personal relationships with God, insisted on good behavior, and butted heads with institutions. They were more advanced than priests.

Max Weber, often called the founder of sociology, made a similar argument. He identified a certain set of archetypes in all religions, most notably the prophet and the priest. Priests, Weber said, are inherently conservative, in the sense that they seek to preserve traditions and order, memory and institution. They emerge from existing social structures and their authority derives from those structures. Prophets, on the other hand, are progressive, in that they come from outside those structures, critique them, and foster reform, renewal, and transformation.

Of course, one can see nineteenth-century Protestant anti-Semitism shining through these arguments. Wellhausen thought Jews and Catholics were less developed than Protestants. Weber was particularly infatuated with what he called “charismatic authority,” the sort of non-replicable authority a person like Moses or Jesus wielded, which emerged from their own personalities and their personal relationships with God.

PRIESTS

Both Wellhausen and Weber tended to be somewhat hard on priests, and modern Western society, with its instinctive suspicion of all institutions, has been happy to go along.

But scripture has much to say about their value, too. Exodus 27:20-21 (NRSV) gives a tremendous explication of what priests are to do.

“You shall further command the Israelites to bring you pure oil of beaten olives for the light, so that a lamp may be set up to burn continually. In the tabernacle, outside the curtain that is before the covenant, Aaron and his sons shall tend it from evening to morning before the Lord. It shall be a perpetual ordinance to be observed throughout their generations by the Israelites.”

The invocation here of the evening and the morning casts our minds back to Genesis 1, to the creation, and to the lighting of a lamp. In that chapter God sets lights in the heavens, and the evening and the morning mark the time of new creation. Priests embody, both in themselves and in their work, the promise that God makes to his people throughout the Hebrew Bible that he is committed to restoring them from the damage caused at the moment of Adam and Eve’s departure from Eden. In Genesis 3 God describes for them what the world will be like now—a world in which they have to work for food, where they are beset by scarcity and pain. But the priests are a sign that this world can be overcome and that God can bring humanity back from our exile.

Over and over again in the Book of Mormon and the Bible, priests—like Alma (both the Elder and the Younger) or like Joshua—act as the rememberers of exile and a living embodiment of what it is to return. They organize rituals, as Joshua does in chapter 4 of his book when he leads his people into Canaan and erects monuments, telling his people that they will then communally remember who they are and where they have come from. They do this, he tells them, so they will know that they were once enslaved in Egypt, and as the Book of Deuteronomy memorably puts it (NRSV):

“It was not because you were more numerous than any other people that the Lord set his heart on you and chose you—for you were the fewest of all peoples. It was because the Lord loved you and kept the oath that he swore to your ancestors, that the Lord has brought you out with a mighty hand, and redeemed you from the house of slavery.”

The rituals the Israelite priests are commanded to perform in the Books of Exodus and Leviticus (this food, not that; don’t mix weaves of cloth in clothing, and so on) might seem odd, but that is precisely the point. God is telling these people that he loves them simply because he loves them, and that he is faithful to them because he has covenanted with them, not because they are more righteous than other nations or because they have earned his regard. Thus, God asks his people to perform rituals and obey commandments simply out of love for him, as a wife might buy this breakfast cereal instead of that because her spouse prefers it.That relationship with God is what priests remember, both in language and life.

Ritual, then, is a way of teaching through action rather than words—though by that I don’t mean that it’s a code to be cracked. Instead, ritual teaches by inducing us to behave in certain ways, to become the sort of person who does ritual rather than the sort of person who knows something. The person who does these rituals is a person who perceives herself the recipient of divine love.

That is the role of the priest: to call us to that remembrance and that sense of being a people, in a relationship with each other and with God. Priests remember the very idea that’s embodied in the creation of priesthood in Exodus—that we can build a people and a community out of a disparate and diverse group. It’s the same thing that happens, ideally, in any given ward.

The Latter-day Saints are descended genealogically from the Methodists and the Congregationalists and the Baptists, out of whose ranks most early leaders of the Church came. These are traditions that in the nineteenth century did not have much time or space for consideration of ritual. Indeed, they were those very traditions that tended to side with Wellhausen and see ritual as a confusing distraction from the things that were really important.

So today many Latter-day Saints who consider themselves progressive tend to emphasize the ethical function of religion (it’s about being a good person) and many who don’t consider themselves progressive will speak passionately about how worthwhile temple attendance is but not have a lot to say about exactly what the rituals of endowment and anointings actually do.

This is a problem that greater attention to priests might help us solve.

PROPHETS AND PRIESTS

The key thing that folks like Wellhausen and Weber overlooked was how often the roles of prophet and priest are mingled in scripture—and indeed, how Joseph Smith seemed to consider himself both at the same time. The prophet Ezekiel is named a priest in the third verse of his book. The prophet Jeremiah is designated as the son of a priest in the first verse of his book, and thus would have been heir to the priesthood too. The prophet Isaiah was known and consulted by kings.

In the Church, there’s sometimes been a conflation of these roles in a way that obscures one or the other. Most recently, we have obscured the priest. Ever since the time of David O. McKay, the current president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles has been ordained the presiding high priest and president of the Church upon the death of the previous president of the Church. (Before McKay, and going back to at least Joseph F. Smith, presidents were set apart, because of Smith’s belief that all apostles already had all priesthood authority sufficient for the new role.)

And yet, since McKay’s time, members of the Church from the Quorum of the Twelve on down have downplayed that title in favor of the title of prophet. From its first issue in 1931 until 1955, the Church News, official newspaper of the Church, did not refer to the current president of the Church with the title of “prophet” in a headline. Instead, it used the title “president.” Even in the body of these stories, as in most Church publications, the phrase “the prophet” referred most commonly to Joseph Smith.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, this began to change. Increasingly, Church publications began to refer to the president of the Church as “the prophet.” There are a number of possible reasons for this. They might include the personal charisma of David O. McKay, who served in that office until 1970. At the same time, membership in the Church more than tripled while McKay was president, marking the gradual transformation of the Church’s administration away from a small community premised on personal relationships toward a worldwide bureaucracy. And that change occurred at the same time as another development that transformed Western culture: the rise of television and the adulation that characterizes modern celebrity culture. Put simply, we might read the transformation of the president of the Church into “the prophet” as a case of making celebrities out of General Authorities—something that is simultaneously quite real, encouraged in much Church literature, and that seems to make some General Authorities vaguely uncomfortable.

There are other possible reasons for the rise of the term “prophet” as well. In the 1970s and 1980s some General Authorities, notably Ezra Taft Benson, began to emphasize the term “prophet” as a way to stress the authority of Church doctrine and policy. In his 1980 sermon “Fourteen Fundamentals in Following the Prophet,” Benson read the role of the president of the Church in primarily doctrinal terms. He declared that the president “is the one living in our day and age to whom the Lord is currently revealing His will for us.” He then advanced fourteen arguments about the role of the president of the Church that overwhelmingly emphasized ideas. In his role as a prophet, the president of the Church could speak on this issue or that; his words trumped those of past presidents of the Church, and so on.

It’s possible to read Benson here as an expression of retrenchment, a movement in the mid-twentieth-century Church to assert the Church’s independence from the world around it, particularly during the cultural upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s. Benson thought American culture after the sexual revolution and counterculture was hopelessly corrupted, and he longed for a Weberian prophet who would heroically denounce it.

And yet, I think that Benson’s insistence that the president of the Church is first a prophet renders his role as primarily verbal. From this point of view the prophet exists to say things; to convey information. That, I think, can lead to a distortion of what the job of this person is and a distortion of what the Church is for.

In other words, overemphasizing the prophetic aspect of the role means overemphasizing the role of language, of doctrine, of believing the right propositions and ensuring the proper ideas are taught. It can make Church members hyperattentive to talks and statements, and lead them to underemphasize the pastoral, day-to-day functions of a priest. If the only job of Church leaders is to convey information and the only job of Church members to assimilate and believe information, the Church itself becomes simply a game of Jeopardy, in which right questions are asked and right answers given. The Church also becomes simply a collection of individuals, people who hear what the right thing is and then go off and do it.

The book of Exodus relates that such a scenario is exactly what priests exist to prevent. If the prophet’s place in the chapel is at the pulpit, the priest’s is at the sacrament table. If the prophet preaches, the priest passes the bread and the water. The priests bind the community together; they remind the community that it is, in fact, a community; they lead ritual and sacrament that embody that memory and do the work of sealing. That is the actual work of the Church, and of any church: to build a community that will lead each member to renewal and belonging.

The prophet Ezekiel was also a priest, and it is significant, I think, that the culmination of his prophecies is a long, long discussion of a temple he prophesies will be built in the New Jerusalem. There are precise measurements of the walls, specifications about the decorations, instructions about the floor plan and the shape of the altar. These are the sorts of seemingly abstruse details that we might imagine a stereotypical prophet denouncing. But Ezekiel lingers over them.

By the end of these eight chapters, we learn why. Ezekiel sees a small stream of water emerging from under the temple. As he follows it, he witnesses it erupt into a gushing river that flows into a desert and transforms it into a fertile valley—the very image of the Garden of Eden. And in that garden there is land both for the tribes of Israel and “the strangers who dwell among you,” who are to be treated as “native-born.”

The functions of prophet and priest may be distinct. But the purpose is ultimately the same: the transformation of humanity into a common people of God, people, prophets, priests and priestesses who both believe and do, both preach and minister. To overemphasize one is to neglect the other, and ultimately, to mistake the purpose of each.

Matthew Bowman is Howard W. Hunter Chair of Mormon Studies at Claremont Graduate University and the author of The Mormon People: The Making of an American Faith and The Abduction of Betty and Barney Hill: Alien Encounters and the Fragmentation of America.

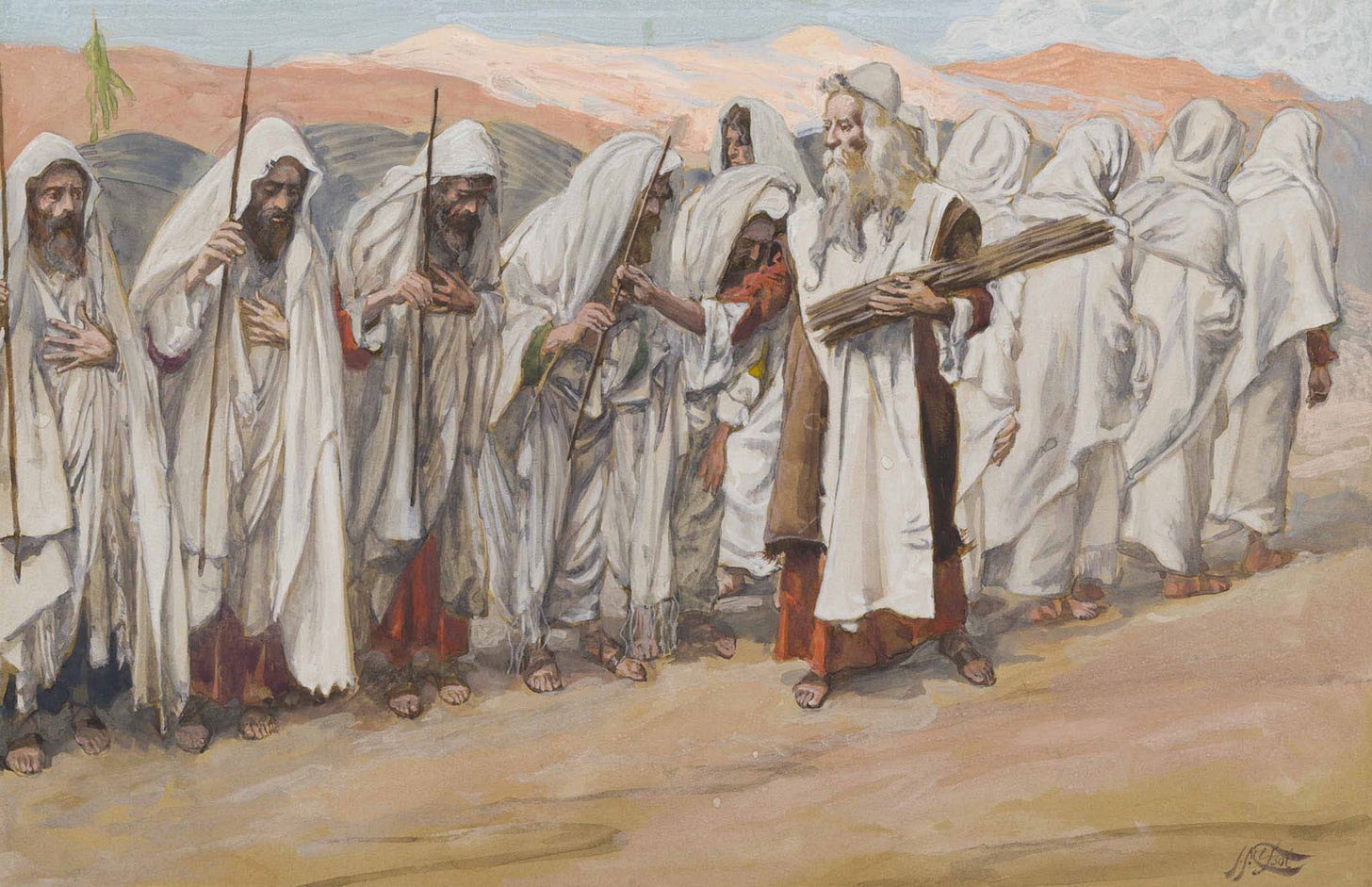

Art by James Tissot.

WAYFARE FESTIVAL 2025

Join us in Park City on July 12, 2025 for a day of invigorating ideas and fresh friendships in a gorgeous setting. Gather with friends, artists, writers, and fellow wayfarers. It will be a feast for the soul. RSVP to come soon.

KEEP READING

Female Embodiment

Learning to see the Mother in the world begins with learning to love our physical bodies—their transient materiality, limitations, and pains, as well as their capacity for awe, joy, and transcendence. By listening to what they communicate, we cultivate their unique wisdom, increasing our capacity to connect with ourselves and each other in loving ways.

OUR LATEST PODCAST EPISODE

Latter-day Saint Art Episode 3: Recovering the History

Jenny Champoux: [00:00:00] Hi, everyone, and welcome back to Latter-day Saint Art, a limited series podcast from Wayfare Magazine. I'm your host, Jenny Champoux. In Latter-day Saint Art, I'll guide you through an examination of the artistic tradition of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Each guest is a contributor to the new book,