The Problem With Miracles

I once saw a beautiful image, a photograph of a nurse standing outside a children’s ward in 1923, preparing insulin syringes for injection. Her clothes were crisp and white, her hair neatly pinned beneath a hat. The tray in front of her was dotted with needles, syringes, and small vials of insulin.

When I looked at it, I didn’t linger on the nurse; my eyes immediately went to the door just to her left, my thoughts to the beds of children awaiting their first, or second, or hundredth dose. Awaiting the little miracle that would heal their bodies for a time.

The miracle that saved my child came nearly one-hundred years before he was born. In January of 1922, Dr. Frederick Banting and Charles Best, a graduate student, isolated insulin in their lab at the University of Toronto. After years of studying diabetes and its lethal effects on humans, they finally had a breakthrough.

A miracle.

Their success was built upon hundreds of years of study. In fact, the first mention of diabetes is found in Egyptian medical texts, written around 1552 BCE. BCE! For millennia, men and women studied the effects of diabetes and worked to cure it. Their labors, though noble and groundbreaking, did not yield the results they’d hoped for. Thousands of parents watched their children literally waste away before their very eyes, “siphoned,” as the Greeks said, of life. Within a few weeks, children lost weight, starving to death as they ate, exhausted as their bodies fought for survival.

Then one day in 1922, a technique researchers had read about, extracting insulin from the pancreas of a dog and injecting it into another diabetic dog, was performed in a lab at the University of Toronto. And it worked. Repeated trials brought about the same results and, just days later, Dr. Banting stood at the bedside of fourteen-year-old Leonard Thompson, “a serious diabetic,” and gave him an injection of insulin. This would begin a series of successive miracles that would save his life.

Many years down the road, I would take that same step, injecting insulin into the skinny little arm of my beautiful three-year-old son. I can’t thank Dr. Banting for saving my son. I can’t send him a letter, care of the University of Toronto, expressing my profound gratitude for the hours he and his team spent in the lab, researching, working, stressing, and then finally finding success. He died years ago, his miracle preserved in a formula recreated millions of times to produce synthetic insulin for diabetics all over the globe.

The Christian world professes to have knowledge of miracles, what they are and when they have occurred. Many of us claim that miracles have not ceased. I, myself, have seen miracle after miracle come about since my son’s diagnosis. In the early days, before we could afford continuous glucose monitors and insulin pumps, I would wake in the middle of the night and hear a voice so loud I would turn to my sleeping husband to see if it was him speaking. But my family was quiet, the hum of the heating unit in the closet outside our bedroom the only noise. And then I would know—the injunction to “check on Henry” had come from somewhere beyond our home.

Without hesitation, I would take Henry’s glucometer, prepare the lancet, and tiptoe into his bedroom. It was so dark in there, his Lightning McQueen night light casting a little glow next to his bed where he was cuddled up tight in his blankie. A tiny light on the end of the machine guided the needle into my toddler’s finger, his flinch the only indication that it had worked, and I would press the drop of blood to a test strip.

The anxiety that filled my body, shivering in my pajamas in our basement apartment, was often justified by the number on the screen. Below 80, we were concerned. Below 50? Henry was in serious danger. Sometimes, after reading the number, I’d return to bed, relieved that he was okay, that his blood sugar was in the target range. But other times, I’d close my eyes and feel the lump rise in my throat, panicking at the too-small number on the screen. I’d make my way into the kitchen, rubbing my eyes as I searched for a fruit snack, and then carefully open the package, gathering the bits of gummy sugar in my palm before heading back to his bedroom.

Henry, more asleep than awake, would chew those lifesaving sweets as I watched, making sure that he didn’t choke and determined to see that he got every single bit of sugar into his mouth where it would, miraculously and mysteriously, end up in his blood. Then, satisfied, I’d place a tearful kiss on his forehead, smooth his blond hair from his eyes, and go back to bed.

But not to sleep.

I can’t recall how many times I lay there, my eyes scrunched tight, holding back the sob and the terror. It takes only once, the endocrinologist said to us, only once. One extreme low, and . . . I hadn’t let the end of that sentence enter my memory. But the fear, the agonizing clutch at my heart remained. As I would curl my body up against the warmth of my husband, I’d spill my gratitude to God for waking me up, for prompting my midnight ministrations to my boy. For another miracle.

But miracles are tricky things.

In the diabetic community, we mourn collectively when others with type 1 diabetes, often young children, are taken too early. One night when a parent didn’t hear the alarm. Or the continuous glucose monitor failed and no alarm went off at all. Or the child stayed up late watching a scary movie, and the adrenaline sent their blood sugar into a downward spiral, unbeknownst to anyone in the room. And then the next day? The worst news.

Where are their miracles? Where are the dreams that jolt parents awake, the voice louder than the alarm clock, the simple thought, I should check before I go to bed? Where are the warnings, the promptings?

I’ve learned in my three-and-a-half decades of life that sometimes miracles don’t make sense. So much of the substance of miracles feels like luck. Yes, miracles are evidence of God’s love, Their infinite wisdom and Their ability to see Their children. They inspire us to discover and invent, bringing about miracles in our day. But miracles raise questions about what they reveal about God’s love. When Christ healed the blind man, were there not others limited by blindness needing such a blessing? Why didn’t He find them all and place His hands on their heads, or simply declare, “Go, see!”? How do we hold both images in our hands: a loving God who brings about miracles and a loving God who allows us to suffer in our fallen world?

Sometimes, it might feel easier to cast judgment. If only they had prayed harder, if only they had gone to church. Oh, there must be more to it than we can see. But this transactional view of God—one that insists that rewards are always tied to actions—doesn’t mesh with our understanding of grace.

Christ saves us in spite of our sins. He declared to those who cast judgment on the blind man, “Neither hath this man sinned, nor his parents” (John 9:3). The same applies to miracles. What would Christ say to those who looked at a mother who’d lost a child to low blood sugar, perhaps disdainfully remarking, If only you were closer to the Holy Ghost, you would have had the prompting to get up and save your child. One mother isn’t more deserving of a miracle than another. Miracles don’t occur based on how hard we pray, how many scriptures we memorize, or how many people we serve. I believe God knows, through perfect love and awareness, when we need a miracle. We love and partake in a gospel, not of transaction, but of relationship.

I don’t always know how to share the miracles I’ve experienced. How do I praise the God who awakened me in the darkness and prompted me to check my baby’s blood sugar when another mother might be crying out to God in the same moment, Why didn’t You? We so often “plead to a God of maybe,” hoping miracles will fall in our laps. I don’t have an answer for that mother. I know I am no more worthy of miracles than she is. I weep with her. Her pain becomes my pain, and all the while, in the back of mind, I thank God that I have not been put in her position.

Why are some people healed while others are not? What of all those babies, those little boys and girls, for whom the miracle of insulin came too late? What would it feel like to read the news of Dr. Banting’s success, moments, days, weeks, years, after you held your child in your arms as they died of diabetes? Their life, their joy, their vibrancy drained from their tiny bodies? To know that you were just short of the miracle? That if they could have held on a little longer, if you had taken them to the right hospital, if . . . if . . . if . . .

Oh, the grief. The anger, the sorrow. The newspapers flung across the room in despair. The raging at the Nobel Prize-winning doctor who didn’t save your child. All of those aching moments, the helpless, terrifying nights as you held your little one while they vomited, their body wasting away, “siphoned” from life.

But then, how can one begrudge another a miracle?

I hope I would be grateful that other children could be saved. But I also know I am not done praying for my own miracles. I put my son to bed every night, praying I will hear the alarm if it goes off. The last thing I look at before I sleep and the first thing I check in the morning is a number, a glucose reading that I trust to be accurate. I worry when my son leaves for school, when he spends the night with his grandparents. Any time I’m not there, any time I’m not in control.

I have to trust that God will hold my son in the hollows of Their hands. I pray for a miracle every time. And, every time, I remind myself of what I believe—that little miracles are waiting for us. Just as the children in the photograph patiently wait on the nurse, I find myself waiting on God, asking that They bring a miracle for me.

The problem with miracles is that they are inexplicable. There is no reason why one child is saved and another is not. Why one mother rejoices and another weeps. The terrible beauty of this non-transactional gospel is that we must make peace with what we don’t have, or what we have that others don’t. On our own individual paths, we must look to God and acknowledge that Their ways are not our ways. Looking at the miracles we do see, whether they belong to us or not, we can say: “Have miracles ceased? . . . I say unto you, Nay” (Moroni 7:29).

Jennifer Bruton is a writer and historian based in Provo, Utah. She's a passionate reader, gardener, crossword dueler (with her partner, Derek), and mother of four boys. Jennifer's debut novel series will be published by Sapere Books.

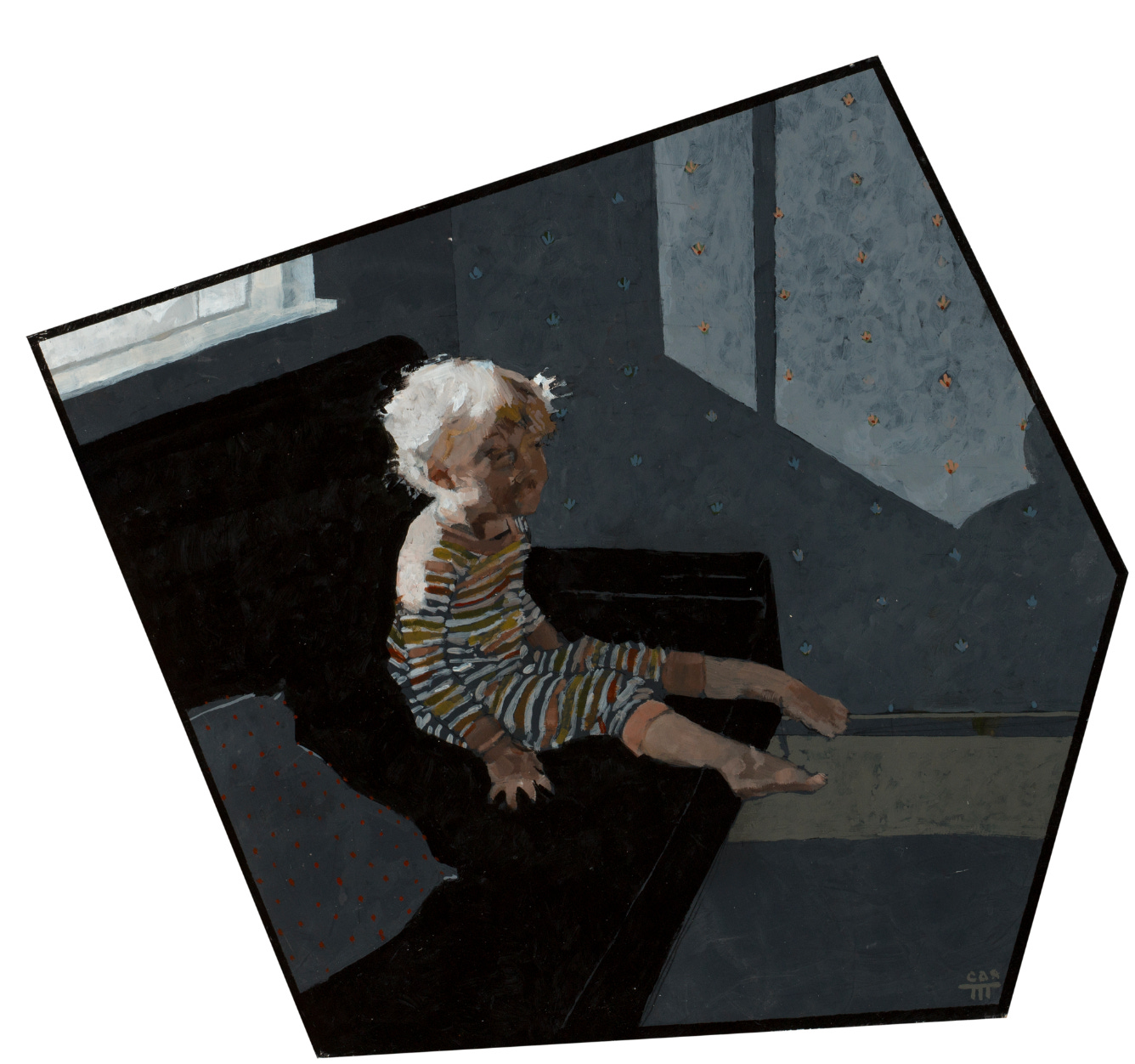

Art by Colby A. Sanford.

I love how you put these painful questions into words.