Myriad writers have noticed the illogic of condemning Adam and Eve for committing evil before they knew what good and evil were. And Latter-day Saints have their own reading of Eden in which the choice to partake of a forbidden tree was...complicated. A transgression en route to a greater good,1 or a transgression of law but not a violation of God’s will or intent for the human family. A “heaven-ordained enterprise” deserving of “reverent honor.”2 In any case, if one believes the primal sin was not sin, then what was the first unambiguous sin recorded in the story of our first parents?

Abelard’s place in Christian history is largely a result of his effort to halt the slide of atonement theology in the direction of retributive justice. He believed the focal point of atonement was the “kindling of love” in human hearts that Christ’s example prompted. We belong to whomever we most love—and Christ’s overflowing mercy and selfless life and death shatter the shell of self-concern and turn us to the source of all goodness and light. It is our freely chosen response to love that makes us Christ’s again.

But Abelard also wrote to challenge what contemporaries were saying about human sin. Since Augustine, original sin had taken deep root, a doctrine which not only imputed guilt to the entire human family, but a paralyzed will as well. Abelard acknowledged that human nature had changed after the expulsion from Eden; our will was indeed inclined toward the natural man. As early as the fourth century writers had begun a taxonomy of sin to which we are naturally inclined: sloth, avarice, gluttony and all the rest. But Abelard resisted the contemporary belief that a corrupt will, sin, and guilt were all a package deal. Or that our inherited inclinations as children of Eve meant we were condemned from birth. He wanted to carve out more space for human freedom in the process—and he found that freedom in the principle of “consent.”

Something in our nature inclines us to anger. The internal motion of our heart happens before we are even aware of it coming upon us. A spark of irritation. Or envy. Or a hundred other inclinations “that flesh is heir to.” Yet in the immediacy of that moment, writes Abelard, there is an interval wherein we “consent” or “consent not” to the impulse that wells up from our depths. It is, Abelard recognized, our response to natural impulses that defines our humanity. A modern philosopher, Harry Frankfurt, agrees. We are not, he argues, “merely a passive bystander or victim” with regard to our desires and motivations.3 We can reflect, we can embrace, or we can resist them. If the story of the Garden has relevance for our own experience of sin—it may be in the first response Adam and Eve chose to their actions.

In any decision we or Eve or Adam has made, time pauses long enough to “embrace or resist” the opportunity to own that action, before that action disappears into pastness. Augustine believed that the present was “the smallest instantaneous moment,” “an interval of no duration.”4 That’s not actually true. Neuroscience and cognitive science alike confirm that the present is experienced as a duration of 2-3 seconds.5 But whether our time of reflection is three seconds or three years, the consent or refusal to consent is always ours to give or withhold. Our bodily selves are acted upon by untold and unseen causes outside of and prior to our control. Biology, genetics, environment. Our eyes can see only .0035 percent of the electromagnetic spectrum; our hearing, our taste, our smell and touch, give us faltering, fragmentary glimpses of an almost infinite reality (access to less than one-millionth, opined Buckminster Fuller).6 And yet that relatively minute stream of data pouring into our brains is being processed by tens of billions of neurons creating a hundred trillion synaptic connections with such “combinatorial explosion that the human brain is capable of forming more thoughts than there are atoms in the universe.”7 Out of that bedlam of unconscious processes and chaos of interactions with a wildering world—no wonder we often get it wrong. Two to three seconds. Or weeks or years. In the moral echo chamber of that present, we own, we “consent” to what we have thought or done or said. Or we disown, reject, resist and repent. As George MacDonald wrote, what matters is “not the sins that men have committed, but the condition of mind in which they choose to remain.”8

“The woman made me.” “The serpent tempted me.” If we look for that paradigmatic moment, that morally instructive part of the story upon which to build our own life of discipleship, it seems to be this: Agency means the freedom to choose. If not our first, impulsive response to the world, then our response to that self we have just witnessed. And in that response, we are free to grow in a more and more godly direction until we are perfect in Christ.

To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."

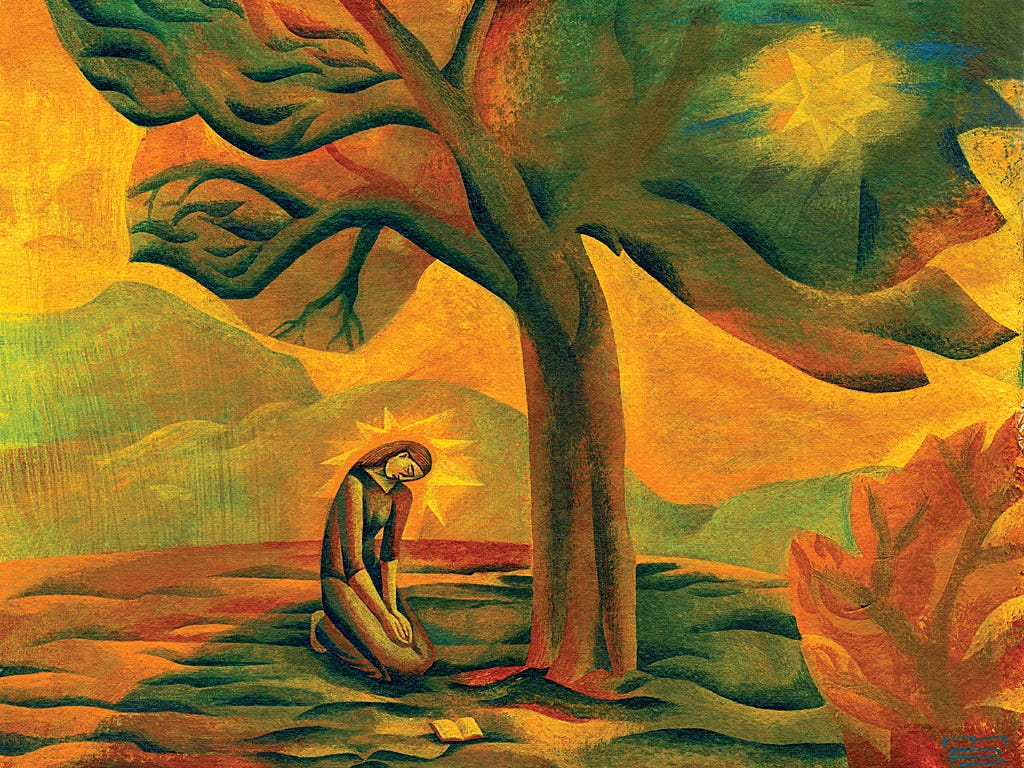

Artwork by Michael Cook.

“Joseph said in answer to Mr stout that Adam Did Not Comit sin in [e]ating the fruits for God had Decred that he should Eat &fall.” Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., The Words of Joseph Smith (Orem, Utah: Grandin, 1991), 63.

President Sarah Kimball, Cited in Boyd Petersen, “Redeemed from the Curse Placed Upon Her: Dialogic Discourse on Eve in the Women’s Exponent,” Journal of Mormon History 40.1 (2014): 155-56.

Harry G. Frankfurt, The Reasons of Love (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 18-20.

Augustine, Confessions 11.15.29.

See for one of numerous reports on this subject Marc Wittman, “How Long is Now? The Present Moment of Consciousness Extended,” Psychology Today (17 May 2019).

Ziya Tong, The Reality Bubble (New York: Penguin, 2019), i.

Holmes Rolston, Science and Religion: A Critical Survey (Philadelphia: Templeton, 2006), loc 504.

George MacDonald, “It Shall Not be Forgiven,” Unspoken Sermons (Whitefish, MT: Kessinger, 2010).