In my first pedagogy training for new teachers, the presenter described the ideal discussion leader as a well-seasoned hiking guide. A good hiking guide knows the terrain well enough to permit exploration without getting lost just as a good discussion leader knows when students can wander around in a text and when they need to stick to a trail of argument. They are familiar with how different trails lead to different vantage points. A good hiking guide loves the ascent as much as the view from the peak; their familiarity cultivates greater attention. A good hiking guide is both a fellow pilgrim and host.

Poet, essayist, and teacher Betsy K. Brown embodies this dual role of pilgrim and host in her first full collection entitled City Nave: Poems. Throughout the collection, Brown demonstrates her range of poetic skill. Her spare and sonically rich language energizes the images and narratives of her poems with a captivating and luminous intensity. Like the flames of votive candles, Brown’s poems breathe and brighten. Brown’s poems move between both inherited forms, such as the sonnet and terza rima, and free verse as the poet-pilgrim seeks for a meter in which faith, art, and relationship can speak authentically. Her poems not only guide the reader along the urban streets of Midtown and across the desolate landscapes of Arizona wilderness, but also trace an interior journey—a spiritual ascension from wandering to belonging, a movement toward love sustained by grace. The four sections of the collection (each named after an architectural feature of a cathedral) mark four chronological movements of the pilgrim: Stairs, Narthex, Nave, and Altar. While the collection as a whole moves from “Dark Ages” where “young pagans . . . scrawl / inky runes into their hands” to the consecration of a home where “it must all be love,” City Nave is, as Amit Majmudar describes, a “synoptic collection” in that each poem rehearses and refracts this whole movement within itself. In this way, City Nave bears all the consistency and variation of a living liturgy that resists simple or reductionistic interpretation.

Each of the poems in Brown’s collection is worthy of a close, meditative read. As such commentary extends beyond the capacity of this review, I hope to highlight moments from each section that supply the reader with a glimpse at Brown’s poetic voice and the architectural shape of the collection.

I. Stairs

Stairs mark both the way to enter as well as an obstacle to entrance; stairs must be climbed. Comprising of fifteen poems, the poems of this section invite the reader to meditate upon our spiritual nature, the powers at work in our movements, and the necessity of grace.

The poet introduces us to a flock of waiting people in “Basilique Du Sacré-Coeur.” Unlike those waiting for a train or plane (“Ode to Penn Station”), these “loiter on the hem” of the steps of the Sacré-Coeur “maybe / hoping to be healed.” Held back by the “billow” of “three / hundred steps instead of five or ten,” “The loiters stretch on and on, / packed tight as pigeons, taking pictures, drinking lukewarm Heineken, / kissing at sunset, and all with their backs to the basilica.” Brown artfully captures the tension of a population simultaneously drawn to the steps of the Church where they are “cradled” and a people unable to “stand before the domes without / keeling backwards and crashing down the grime-stained steps.” The poem concludes with the haunting lines: “So they sit upon the stone skirts, crouching toward the deep streets / of the world, held there.” They are all at once held near to the hem of the basilica by desire, held away by its austerity, and held captive by the ways of the world they cannot escape. These two poems appear to suggest our spiritual condition before we have ascended the stairs and passed into the ark of the church. All displays of power reveal our powerlessness. Our desire outreaches our ability. We cannot make ourselves ascend.

In the penultimate poem of this section, Brown brings us to the threshold of the sacred through the confessional prayer of “Saint John the Unfinished”:

My body is a broken temple of the Holy spirited away by cigarette smoke and city grime. I grind my teeth, wanting to be washed. The nave of my neck lies long and empty like an abandoned subway tunnel; the domed ceiling inside of my skull is gray and bare, waiting to be turned into art. But as of now, no one crosses himself before peering into me. Shroud me in scaffolding. I want to be wrapped up in metal poles, white plastic, and construction workers. Roll a stone over my whitewashed mouth. Let me lie. Unveil me someday.

The body of Saint John serves as an index for a city and its temples of transitions. The once glittering Penn Station has decayed into an image of an abandoned subway. The “gray and bare” space within Saint John’s skull brings to mind the “wide, gray cells” of airport terminals. Saint John’s prayer is punctuated with “want,” a word which expresses both his desire and underscores his own emptiness.

The hoped-for transfiguration demands for Saint John, and perhaps for us as well, a death as good as grace.

II. Narthex

Traditionally, the narthex marks the space for catechumens and penitents. It is the space of preparation, reorientation, and the place where one is baptized—“buried with Christ” and raised to a new identity. It is a site of reconciliation, of coming to be who one ought to be.

Brown plays upon themes of catechism, death, and rebirth throughout this section beginning with “Eulogy To The First Ms. Brown,” an aunt, “a science teacher, not wife / Or parent, but a mother all the same.” In imagining her aunt as a questioning child who receives a “wry / Teacher’s reply” from her father the speaker situates herself within a lineage of educators fielding the endless “whys on whys” of children. As much as the speaker cherishes her heritage of disciplined doubt, she wrestles with its demands:

Did it ever feel too vast

To you, Aunt Lin, that map that curses, blesses

Us with endless, shining roads?

I don’t know, I say again. It messes

With me, cruel doubt, and gnaws and pokes and goads—

Doubt about adding, atoms, afterlife,

Doubt about what might survive or explode—In turning to the master teacher, the poet observes how Aunt Lin’s commitment to the discomfort of doubt leads her pupils to light, a “conflagration,” a “flash of something true,” a “consolation.” Under the artful instruction of the first Ms. Brown, doubt yields to wonder. Although the speaker imagines her Aunt inhabiting a new life “Of light, and heat, and burning—much like a star,” the children voice their lingering doubts asking, “Is that where you are? Is that where we’ll go?” The other side of death— whether it is the death of the old self in baptism or the death of the body—is an innate mystery only known to those who pass through that darkness.

We are invited to a kind of death, as we are invited into doubt, as students who follow a good and trusted teacher. Brown’s masterful mirror poem, “Pupils,” plays upon the homonym, weaving together the act of seeing and the student as moves between light and darkness.

The tunnel with the light at both ends: The joy of and the fear of Looking into it honestly And saying just what you mean, A sometimes-shuttered window, yawning Often in the dark, tightening in brightness, A circle, a space, The soul of a face, A student. A student. A soul of a face, A circle, a space, Often in the dark, tightening in brightness, A sometimes-shuttered window, yawning And saying just what you mean, Looking into it honestly, The joy of and the fear of The tunnel with light at both ends. The tunnel with the light at both ends:

The form of the poem is suggestive of a transformation in which we continue to be what we are and also entirely new. We pass through the darkness of the tunnel with joy and fear, looking into ourselves honestly and find ourselves in the light on the other side. If “Pupils” summarizes our activity in this movement, “Plane God” reasserts our own powerlessness to move ourselves and the necessity of grace. In this poem, we join the speaker in the “embrace” of a plane tearing “through the veil of violent wind,” ascending into a “wind-wrought, storm-torn, sky road.” Like Noah borne in the ark across the flood, the speaker passes through the deluge “powerless in this great / Powerfulness.” Even while the speaker meditates on her own limitations, she wonders:

Later, if we hatch from this square foot of Space, will we flee from this great hug, reach out Our own arms, and attempt to rise?

We may as well ask: Will those who are born of this God also do as He does?

III. Nave

At last we enter into the nave, the central space of a cathedral wherein a congregation gathers for corporate worship. Within this section many of Brown's poems explore relationships as the speaker locates herself within a vast spiritual community populated with saints, friends, students, sinners, and strangers.

In “The Art of Loving,” the speaker compares the practice of loving one’s neighbor to a troubadour’s skill with his own instrument: “playful yet precise.” The speaker longs to love with “All fingers dancing, never strained by self / Or hesitation” and recalls how often their love for another is inhibited by “The tremor of a grip too tight,” “the sound / Of hollow distance,” or “the furrow of fear.” The work of love is truly seen and also recognized as being beyond the speaker’s—and our own—abilities. We are all like artists striving to produce the vision of their work in spite of the limitations of their skill. The poem concludes:

Release and practice, practice and release — Until the dance of my hand moves within A Spirit wiser than my mortal reach.

In this final stanza, the speaker invites us into the mystery of sanctification. We must relinquish our effort and yet practice fervently. We must both surrender and obey. Within the space of releasing and practicing, we open ourselves to the Spirit who fulfills in us the art of loving.

Brown continues to explore this mystery of grace in the titular poem, “City Nave.” Beginning with the imperative, “Stand on your head” the speaker claims that one can only see the church as it truly is from the outside by seeing it upside-down. Our upside down view of the cathedral reveals to us “A small ship on a violent ocean.” In spite of the “bitter gales” of the shifting city, the ark of the church remains stable, “unchanging.” The speaker invites us to “swim along the sidewalk to her door; / Turn, tossed explorer, right-side up again.” The speaker invites us to bring ourselves to the threshold, yet it is the “mighty haven” herself which

Drags in the drowning to her drier floor

And bears the wounded through her healing hold

And bids you drink the drink, and eat the food. We come, and yet we are ultimately brought into shelter and nourished by a yet more powerful love. Brown’s language echoes George Herbert’s poem, “Love” in which Love personified “bades” the speaker to a table where they may “sit and eat” of Love itself. Grace ushers us to a table, an altar, where we are ultimately united in Love.

IV. Altar

In the final section, Brown explores communion and union on this side of eternity through a variety of images: her students playing volleyball, shared grief for the death of a student, and marriage. In only a few short poems, Brown directs us to attend to the glimpses of eternity in our midst and reminds us of the patient endurance required until all is made right and restored.

The whole narrative of humanity’s movement from fall to grace is rehearsed in Brown’s poem “Be Fruitful and Multiply.”

So, what is fruit? A star upon a bough, A drop of sweetness buried in a jungle Of vines and thorns, the treasure in the tangle, The pulsing life emerging from a vow, The golden-knowledge we cannot have now, Walled-in and waiting, guarded by an angel.

In meditating upon fruit we are prompted to consider the giftedness and the thorns of the world, paradise and exile. In the second stanza, the speaker turns our attention to oranges “green / And meager from the blight.” Like a new Adam and Eve commanded to cultivate and fill the earth, the speaker and her spouse “buy a tree.” Brown’s speaker models patient hope in planting an orange tree in a desert and trusting that this which belongs to them will “bear much for us someday.”

Brown concludes the collection with the poem, “Buying a House on the Feast of Saint Francis,” in which the poet reflects upon the life of St. Francis and a husband and wife claiming a home as two ways to live out a life marked by love. Whereas St. Francis “sells the final book,” the newlyweds “combine our books and organize / Them into genres alphabetically.” St. Francis “owns nothing,” and the homeowners park “cars / Like conquistadors.” St. Francis “knows that to love a thing / It cannot be his.” The couple “Will know that for a thing to be ours we / Cannot love it too much.” Whether one rejects all ownership or claims “a piece of earth,” a life graced with love pours forth love in return. Whereas St. Francis loves the world by making it all his home, the speaker declares: “We will know to / Be home in a thing, it must all be love.”

From the steps of the Basilique Du Sacré-Coeur and the streets of New York to the threshold of a home, Brown’s poems chart a journey toward love in which the pilgrim becomes host. Just as the poet welcomes the reader within the rooms of the poems to lament, doubt, and ultimately receive, so the reader of City Nave must turn from the pages of Brown’s poems to the world before them in love that we may all be brought back home.

Kaylene Graham is a poet, essayist, editor, and educator.

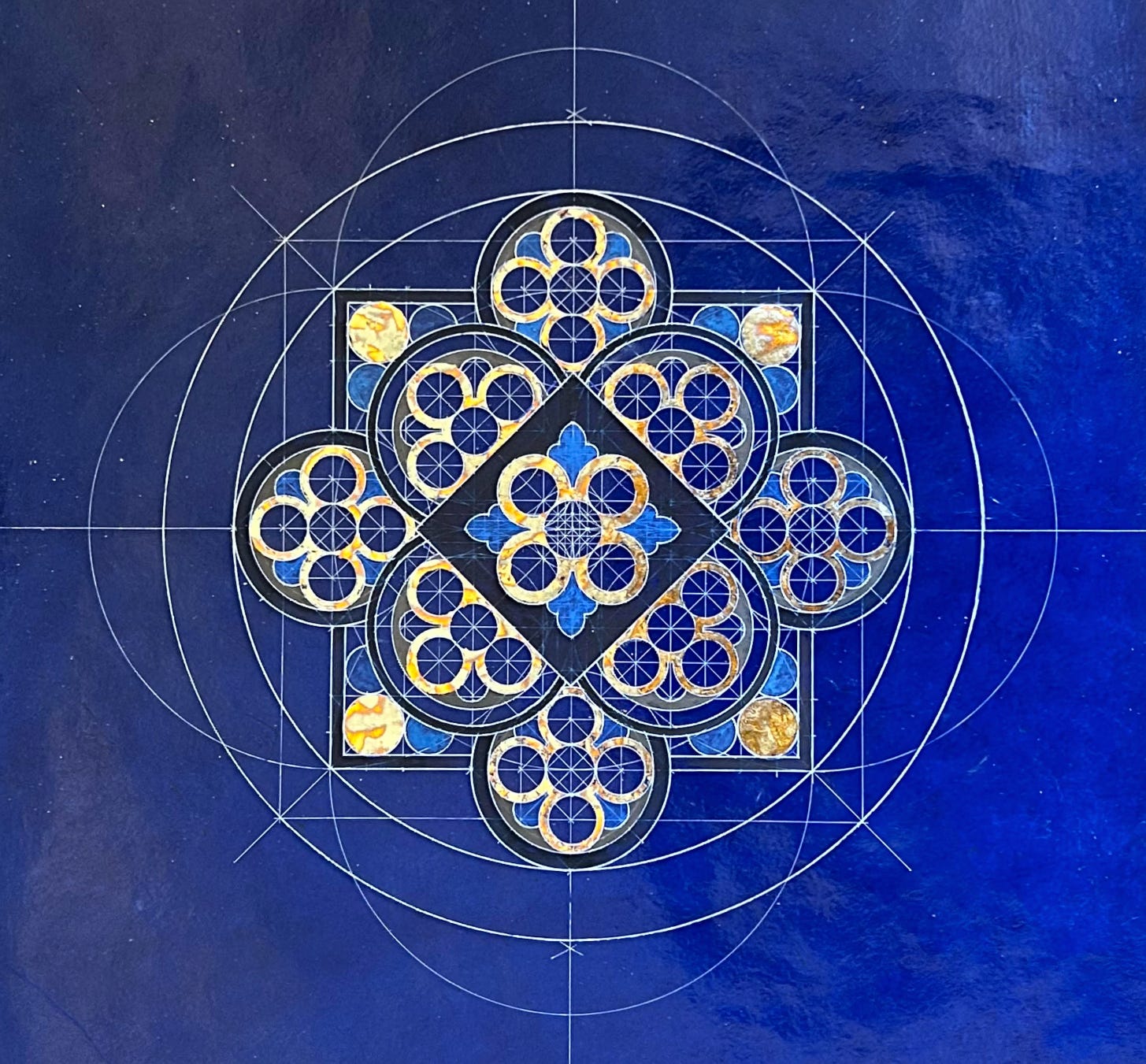

Art by Lisa Delong. Follow her at @lisavalkyrie.