The Olive Tree's Secret

To read the opening verses of Zenos’s allegory of the olive tree, as reported in Jacob 5, is to be plunged into a crisis of disease. Because of its great age, the olive tree to which Zenos likens the house of Israel has begun to decay and to perish. When its main branches wither, the master of the vineyard instructs his servant to “cast them into the fire that they may be burned” (Jacob 5:7). Olive wood is a valuable, fine-grained lumber used anciently alongside or in place of other hard, durable woods like ebony and cedar, so the branches would not have been burned unless they were thought to be diseased.1 The allegory begins, then, with a fear of infection.

During a nationwide smallpox outbreak at the turn of the twentieth century, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had to decide where to seek protection from and treatment for a disease that still killed 15–20 percent of those who contracted it. Public officials encouraged vaccination or inoculation, but many Church members regarded this advice with suspicion, distrusting the motives and methodologies of religious outsiders often pejoratively identified as Gentiles. Instead, they sought advice from within the faith community. Ben Cater reports that “church circulars criticized vaccination while advising Mormons about botanical and faith healing, and dietary health. Churchgoers were counseled to receive the anointing of oil, and priestly blessings by church elders. The Deseret News published information about folk therapeutics, including dried onions, rumored to be a prophylactic, as well as tea made of sheep droppings.” So confident were they in the efficacy of priesthood blessings, and so wary of ideas originating outside the faith, that they were willing to place their trust in fecal teas rather than modern medicine, limiting their search for solutions to the confines of their own congregations.

The tame olive tree in Zenos’s allegory is a symbol of the house of Israel—the faithful who have been gathered into covenant communities. But when that tree becomes diseased, the Lord of the vineyard instructs his servant to seek a wild olive tree. The book of Romans suggests that this wild tree is a symbol of peoples living outside the covenant, “you Gentiles. . . . And if some of the branches be broken off, and thou, being a wild olive tree, wert grafted in among them,” then these Gentiles would receive the strength of “the root and fatness of the [tame] olive tree” (Romans 11:13–17). Zenos’s allegory identifies the remedy for disease within the covenant community as the integration of peoples from outside that community, through grafting.

In Sunday School lessons on the allegory, I have often heard this process of grafting wild branches onto the tame rootstock be compared to missionary work, where the point of the exercise is a transformation of outsiders by their integration into our own covenant community. After a long time, the Lord of the vineyard examines those wild branches grafted onto the original tree and concludes that “because of the much strength of the root thereof the wild branches have brought forth tame fruit” (Jacob 5:18). In other words, peoples from outside the house of Israel have been transformed by their integration into the body of Christ. This process might seem to suggest a one-way transfusion of virtue from the covenant community into the new convert, affirming the identity and essential goodness of those who are already part of the house of Israel. But every interaction or incorporation alters both parties. When healing power flowed from Jesus Christ into the woman with an issue of blood, she immediately “felt in her body that she was healed of that plague,” but Jesus also knew himself altered by his encounter with her and felt “that virtue had gone out of him” (Mark 5:29–30). Missionary work might transform the convert, but it also transforms the body of Christ. Grafting is an exercise in the creation of new, hybrid organisms.

Noah Webster’s 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language defined the word graft with reference to disease: “To propagate by insertion or inoculation.” In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, inoculating patients against smallpox involved the insertion of contagious foreign matter—most often, pus from a ruptured cowpox sore—into a small diagonal incision opening up a flap of skin, typically on the patient’s forearm. Because this practice resembled the method by which new stems were inserted into diagonal incisions on a tree trunk or its main branches, the words graft and inoculation were once synonyms, but their meanings diverged over the course of the nineteenth century.

Fruit borne by an olive branch grafted onto existing rootstock is visible and tangible. The fruit borne by a smallpox inoculation is largely invisible. A patient might experience swelling and redness at the incision site, but the most important results of an inoculation against disease are internal, detectable only with a microscope. Foreign proteins from the virus, introduced to the body through inoculation, stimulate the production of new B cells in a patient’s bone marrow, and these B cells produce antibodies designed to bind to the virus and eliminate it from the body. Marrow in the bones allows us to encounter foreign and potentially dangerous substances and emerge stronger, with more robust defenses against that which would actually harm us and a greater tolerance for that which is merely strange or unfamiliar.

The Lord of the vineyard in Zenos’s allegory observes tame fruit on the wild branches grafted onto his original tree and infers that this transformation of the wild branches is an expression of changes taking place invisibly within the original tree. He instructs his servant, “Behold, the branches of the wild tree have taken hold of the moisture of the root thereof, that the root thereof hath brought forth much strength” (Jacob 5:18). Grafting wild branches onto the tree leads to the extraction of additional, unseen strength from its roots; the tree has been transformed by the branches even as the branches have been transformed by the tree.

Some Latter-day Saint parents living through the smallpox epidemic of 1900 withdrew their students from public schools rather than comply with the order that schoolchildren living in districts affected by smallpox be vaccinated. Skeptical of medical professionals who worshiped in Catholic or Episcopalian churches and who expressed a belief that the day of miraculous healings had passed, they accused doctors of profiting from the distribution of ineffective and dangerous treatments. They could not embrace religious foreigners, whom they viewed as vectors of disease. Ironically, Cater notes, Latter-day Saints leaving Utah to proselyte among the nations were also transmitting smallpox around the globe:

The British Medical Journal reported five cases of the disease at missionary headquarters in Nottingham, England, apparently contracted after missionaries received contaminated letters from Salt Lake City. In Scandinavia, Mormon apostle John Henry Smith stated that “some Elders . . . having the small pox [sic]” were spreading the illness. An outbreak occurred in New Zealand where health authorities traced the virus to missionaries recently arrived from Utah.

Even as the Saints in Utah barricaded themselves against the intrusion of ideas promoted by individuals outside their religious community, they sent missionaries infected with smallpox across oceans and continents in the hope that Gentiles would listen to their message and be converted, gathered into the house of Israel.

In North America, one of the first advocates for vaccination was an enslaved black African man named Onesimus, who lived in the household of Cotton Mather, a prominent Massachusetts minister and physician. Mather hoped to convert Onesimus and taught him the gospel of Jesus Christ, but the behavior of Onesimus left the minister with doubts about his servant’s commitment to Christ. Perhaps it was Mather himself that Onesimus was uncommitted to, or maybe it was the legal and religious framework of laws identifying him as human property. Unwilling to remain a slave, Onesimus eventually saved enough money to purchase his freedom. Or, rather, he paid Mather enough money that the minister could purchase another enslaved black African, who served Mather in his stead. In return, the minister made provisions for his emancipation, and Onesimus left the Mather household.

Some Grafts Never Take

In Genesis, when Jacob left the household of his father-in-law, the sons of the family accused him of stealing their inheritance. Somehow the green-and-white branches of poplar that Jacob erected in front of rutting cattle had caused the animals to birth speckled and ringstraked offspring—an image or idea had been transmitted and made manifest in the flesh. Although Jacob had married into the family, Rachel and Leah lamented that their father, Laban, now regarded his daughters as foreigners and slaves, asking, “Is there yet any portion or inheritance for us in our father’s house? Are we not counted of him strangers? for he hath sold us” (Genesis 31:14–15). Instead of remaining a single household, into which Jacob and his daughters were incorporated, Laban’s family fractured.

Lehi’s family also fractured, divided irreparably into rival groups led by his two sons, Nephi and Laman. In the promised land, the Nephites remembered their identity as the covenant people of the Lord while the Lamanites “hardened their hearts against him, that they had become like unto a flint; wherefore, as they [the Nephites] were white, and exceedingly fair and delightsome, that they [the Lamanites] might not be enticing unto my people the Lord God did cause a skin of blackness to come upon them” (2 Nephi 5:21). This family division seems to be represented in Zenos’s allegory, in verses describing a branch broken off from the tame olive tree and transplanted “in a good spot of ground”—Lehi’s promised land. The servant nourishes this branch until it matures into a larger tree but discovers that “only a part of the tree hath brought forth tame fruit, and the other part of the tree hath brought forth wild fruit” (Jacob 5:25). I have long squirmed at the racist syllogism these passages seem to invite. If white skin is a sign of Nephite identity; if Nephites are the tame fruit in this passage of Zenos’s allegory; if the tame fruit is a symbol of covenant Israel—is white skin a symbol of covenant Israel? The contrapositive conclusion has already led to so much evil and is so troubling that it must not be named.

As he returned to Canaan, Jacob feared for his life. More specifically, he feared that his brother Esau, whom he had cheated of his birthright and blessing, would kill him and his family. When Isaac blessed Jacob, he said, “Let people serve thee, and nations bow down to thee: be lord over thy brethren” (Genesis 27:29). Esau, learning of this blessing, offered one of the most plaintive petitions in the Bible: “He cried with a great and exceeding bitter cry, and said unto his father, Bless me, even me also, O my father. . . . Has thou but one blessing, my father? bless me, even me also, O my father” (Genesis 27:34, 38). And so Isaac offered Esau a blessing as well, announcing that he would “serve [his] brother” but also promising that “when thou shalt have dominion, that thou shalt break his yoke from off thy neck” (Genesis 27:40). In other words, Esau received an assurance that he would one day be freed from his subservient status. As Jacob’s family approached, Esau advanced to meet him with four hundred men; his day of dominion was at hand.

During the night before he was to see Esau again, Jacob “wrestled a man” for hours, and though his “thigh was out of joint,” Jacob would not let go but insisted that the man bless him (Genesis 32:24–25). Perhaps he hoped for a blessing of strength as he approached his brother’s army. But instead of a promise that he and his family would be safe, Jacob was given a new name reminding him of his weak and dependent state: Israel.

One translation for the name Israel is the phrase let God prevail. Jacob could not hope to overpower his brother’s army or to buy his favor with gifts of livestock. He could only pray that a spirit of forgiveness would prevail in his brother’s heart, and manifest his own contrition by bowing to and weeping with Esau. Although Esau is often derided for selling his birthright, he is the hero of this story—the one who abandons a grudge to embrace an estranged brother. In his sermon on the meaning of Jacob’s new name, President Russell M. Nelson encouraged all members of the Church to follow Esau’s example and “lead out in abandoning attitudes and actions of prejudice,” particularly racial prejudice. He also declared, “I assure you that your standing before God is not determined by the color of your skin. Favor or disfavor with God is dependent upon your devotion to God and His commandments and not the color of your skin.” Readers of the Book of Mormon, he suggests, should be slow to assume that divisive labels and external signs—black and white, Nephite and Lamanite, tame and wild—reflect divine or eternal distinctions.

In the olive grove at Gethsemane, Jesus repeatedly prayed that his followers “may be one; as thou, Father, art in me, and I in thee, that they also may be one in us. . . . that they may be one, even as we are one: I in them, and thou in me, that they may be made perfect in one” (John 17:21–23). My tendency, in reading the allegory of the olive tree, is to label and track the story’s many moving parts—which branch of the house of Israel gets planted in a good spot of ground, and which is planted in “the poorest spot in all the land”; which wild branches bring forth tame fruit, and which branches from the original tree bring forth wild fruit (Jacob 5:21). But perhaps the point of all this grafting is to lose sight of provenance and pedigree, thinking less about the allegory’s moving parts and more about the resilience and strength cultivated through hybridity, as so many different olive trees are made one. Everyone is invited to covenant with Christ, and the house of Israel is enriched by the diversity of its membership as strangers and foreigners are grafted in like wild branches.

In 1721, when the smallpox arrived in Boston, Onesimus had been gone from Cotton Mather’s house for five years. But even after Onesimus had left, Mather remembered what his enslaved African servant had taught him about inoculation; the benefit of his exposure to foreign ideas lingered even after Onesimus had moved on. Benjamin Franklin and other Bostonians mocked Mather for inoculating the members of his household and those in the broader community willing to trust the foreign perspective and the foreign body of Onesimus. Fearing that inoculation might actually spread the smallpox, instead of immunizing against its worst effects, someone even threw a grenade into Mather’s house.

Not All Grenades Explode

One editorialist wrote that any minister who embraced inoculation would become “a sooty Coal in ‘The blackest Hell,’ and receiveth the greatest Damnation.” To accept the medical knowledge of Onesimus was to be racialized, rendered Black and a foreigner in the eyes of the community.2 Fifteen years later, Benjamin Franklin’s four-year-old son contracted smallpox and died. At the end of his life, it was Franklin’s greatest regret “that I had not given it to him by Inoculation.”

Although the Church initially adopted no official position on how its members should respond to the smallpox, Presidents Lorenzo Snow and George Q. Cannon of the First Presidency eventually issued the following statement: “While we have regarded it largely as a matter of individual choice, we have felt reluctant to express ourselves publicly upon it. Now, however, we feel to publish the foregoing as our conclusion; and we therefore suggest and recommend that the people generally avail themselves of the opportunity to become vaccinated.” The First Presidency issued follow-up calls for its members to be immunized against various diseases in 1978 and 2021, but Church members continue to be divided in their views of the efficacy and safety of vaccines. The fear of welcoming a foreign entity into our bodies persists.

Of course, our bodies are awash in foreign entities; scientists estimate that there are more bacteria in the average adult body than human cells.3 We are, already, hybrid creatures, in more ways than one. In addition to the bacteria we carry, our human cells also host the material of viruses with which our ancestors were infected. As Eula Biss writes,

A rather surprising amount of the human genome is made up of debris from ancient viral infections. Some of that genetic material does nothing, so far as we know, some can trigger cancer under certain conditions, and some has become essential to our survival. The cells that form the outer layer of the placenta for a human fetus bind to each other using a gene that originated, long ago, from a virus. Though many viruses cannot reproduce without us, we ourselves could not reproduce without what we have taken from them.

Like the olive tree of Zenos’s allegory, our survival has been facilitated by the grafting of wild branches onto our genome, drawing forth new strength and capacities. An ability to metabolize the foreign and the unfamiliar is essential to our personal and collective well-being—it is, quite literally, a welding link between generations, binding the hearts of the mothers to their children and the hearts of the children to their mothers.

Zachary McLeod Hutchins writes about the restored gospel of Jesus Christ in Fort Collins, Colorado, where he lives with a wife and children who deserve better.

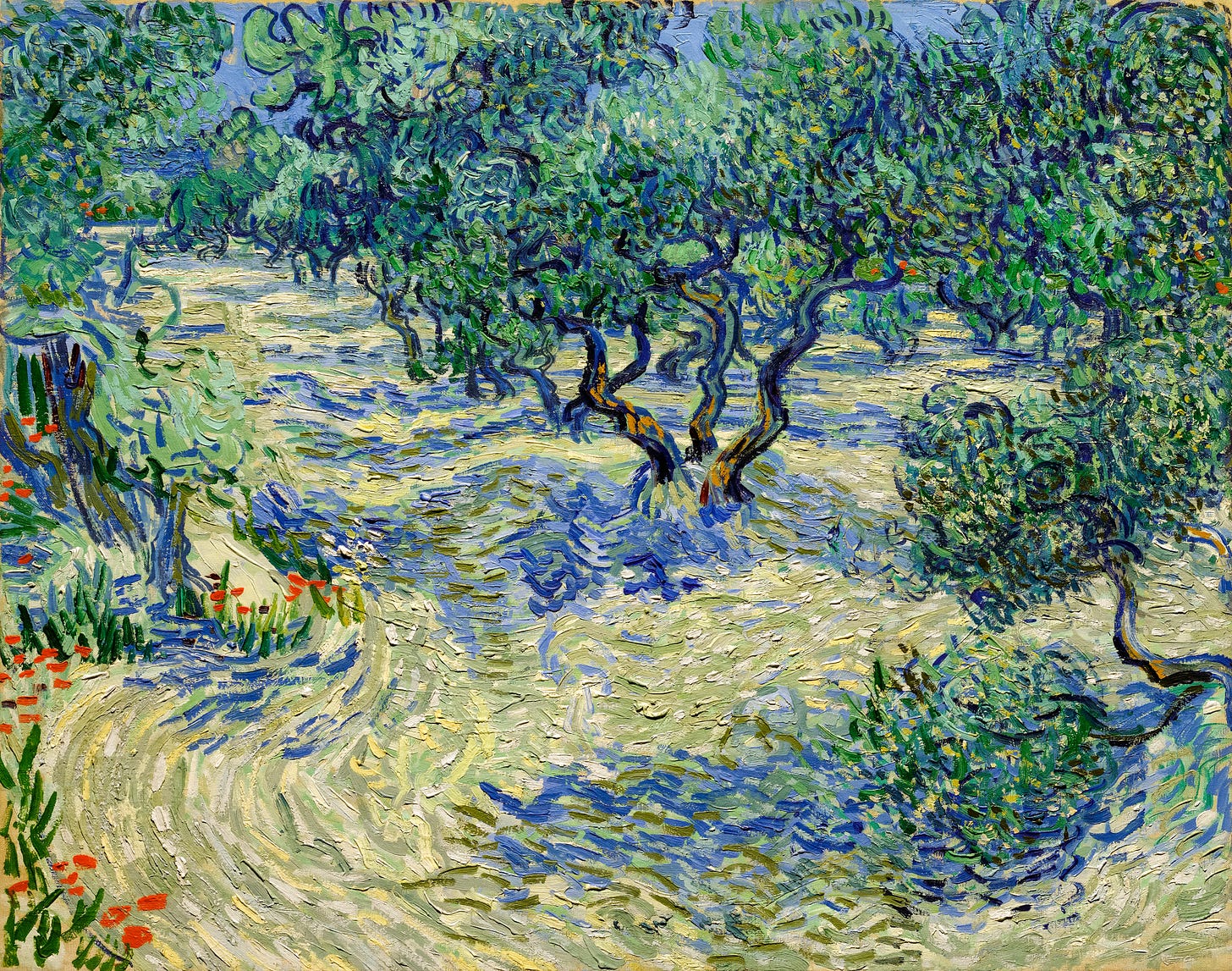

Art by Vincent van Gogh.

In Solomon’s temple, for example, olive wood was used for the doors into the Holy of Holies, and within that chamber, two cherubim of olive wood were installed (see 1 Kings 6:23–35). As Wilford Hess and his coauthors observe, the wood was “likely to have parasites and pathogens, and one of the best ways to reduce the inoculum potential is to burn the infested plant materials.” See Wilford M. Hess et al., “Botanical Aspects of Olive Culture Relevant to Jacob 5,” in The Allegory of the Olive Tree, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and John W. Welch (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994), 550.

The New-England Courant, issue 18, November 1721. See also The Boston News-Letter, November 20, 1721.

“Thoroughly revised estimates show that the typical adult human body consists of about 30 trillion human cells and about 38 trillion bacteria.” See Ron Sender, Shai Fuchs, and Ron Milo, “Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body,” PLoS Biology 14, no. 8 (2016).