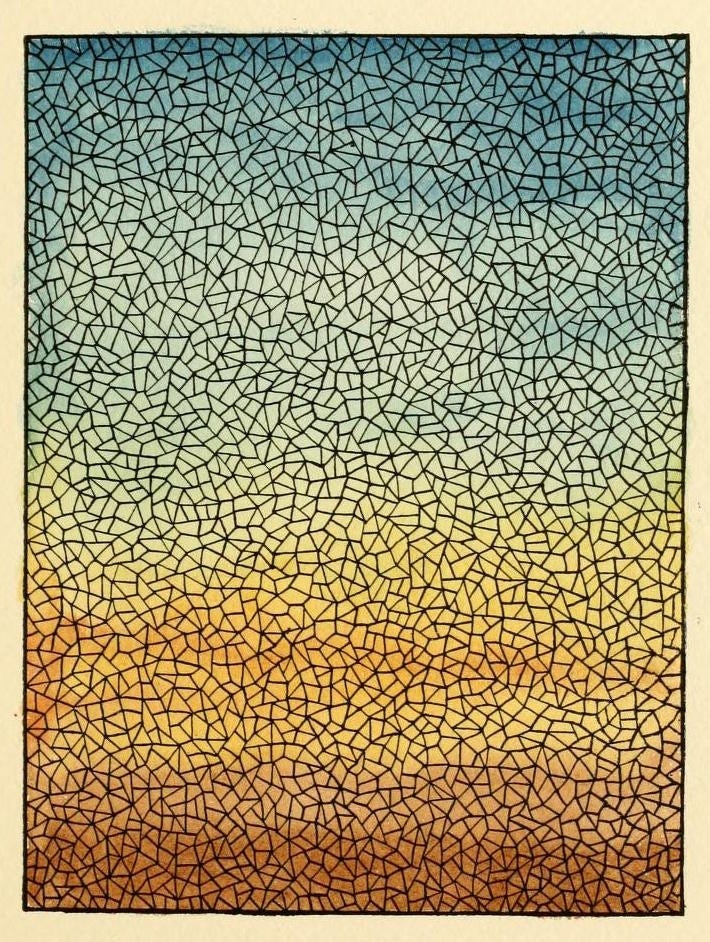

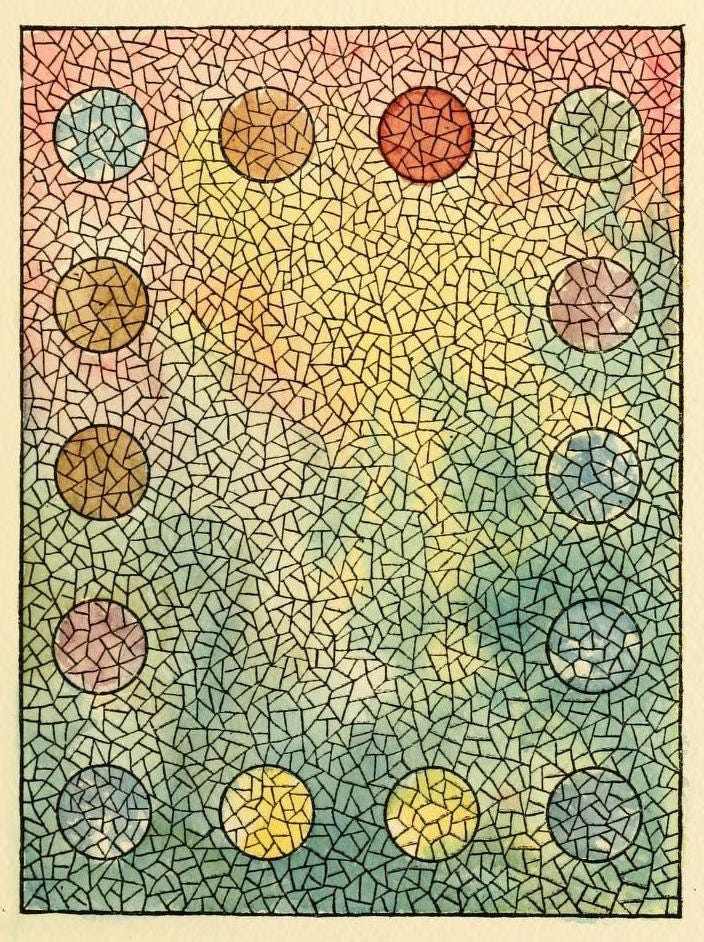

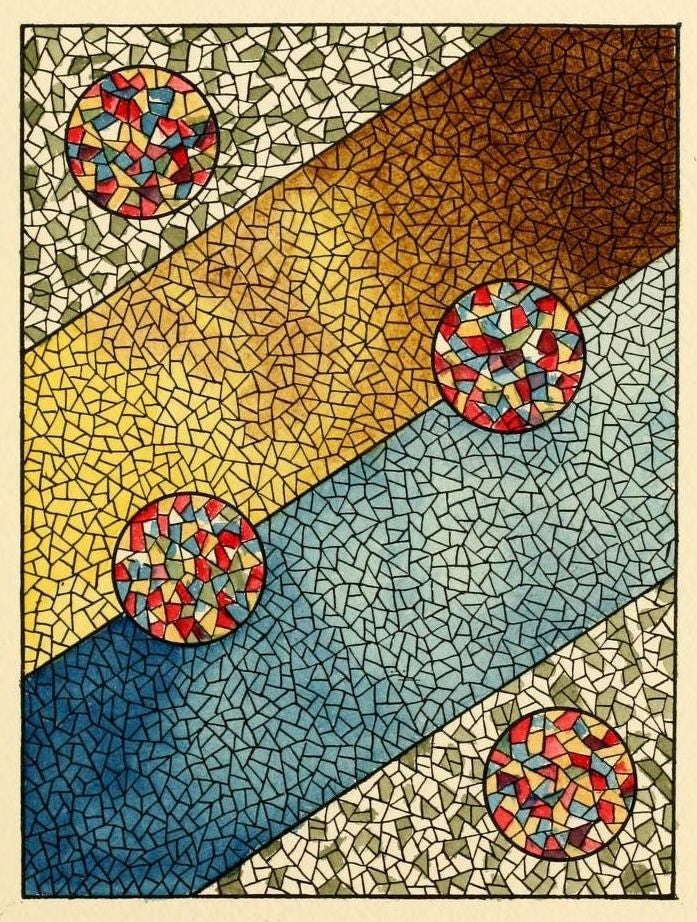

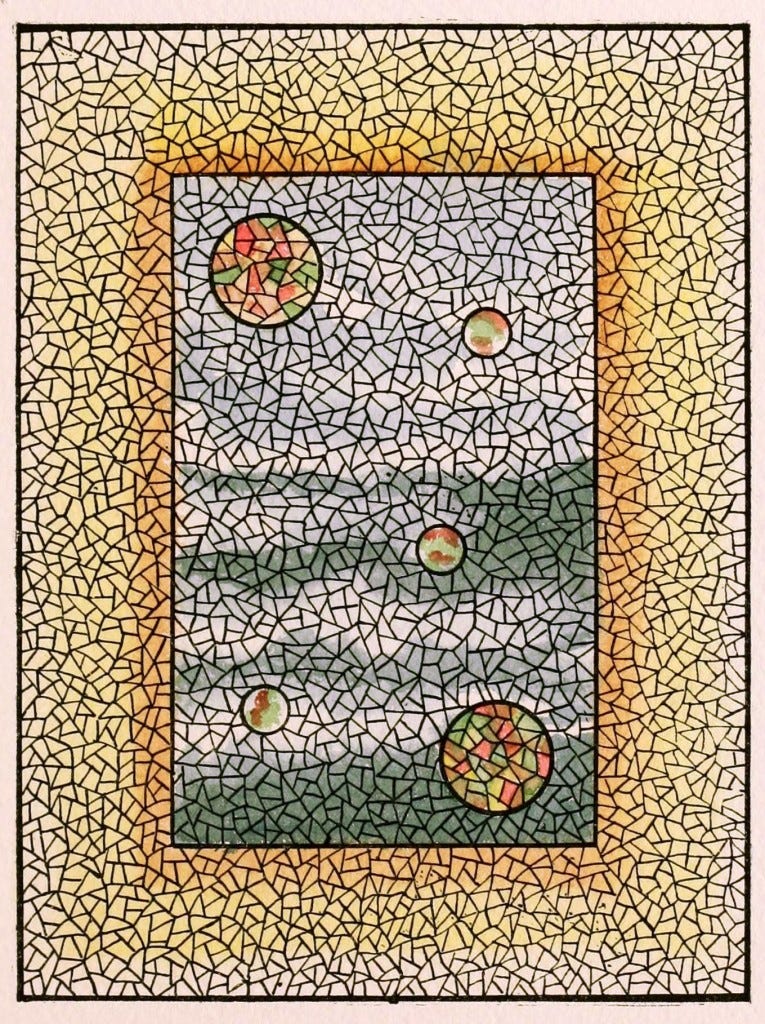

As I read Benjamin Park’s new biography of Mormonism, American Zion, the image of a kaleidoscope kept asserting itself. The miracle of a kaleidoscope is that it takes apparently unrelated fragments of color and shape and tosses them together such that resulting patterns can capture our attention or can even strike us as arresting or beautiful. Indeed, out of a kaleidoscope’s random individual elements, something like fractals emerge—patterned evolutions of color and shape wherein the whole is much larger than the sum of the parts. While Park’s focus is insistently secular, and his framing of the events seeks to outline naturalistic currents of cause and effect, for me, the picture that emerges from the overall narrative arc suggests a beautiful chaos behind which traces of divinity nonetheless emerge.

Theologically, this image seems apropos when considering the religious history outlined by Park. It will always remain astonishing that a church that originated with a mostly unlearned farm boy in upstate New York at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and which, when formally incorporated, had only a small roomful of members, grew to become not just one thriving world religion, but many. As faiths—like fractals—tend to do, that original church split, and split, and split again. First over whether Joseph was the sole owner of the gift of seership; later over who should lead the church after Joseph’s death; later still over whether the church should go West; and then over what should be done after the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints abandoned polygamy (some other branches kept the practice); and finally, in more recent years, over whether that same institutional church has abandoned the tenets of the religion established 200 years ago by acceding too much to the demands of modernity.

The churches flowing from that original First Vision and all that followed are their own fractal—and the image we see of the ramifications branching out over time form a breathtaking pattern, full of complexity, intrigue, nuance, devotion, and beauty.

Because I’m a lifelong member of the LDS church, the fractal that most struck me was not the varying branches of restored Christianity that grew out of that original theological trunk but, rather, the fractals that swirl within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. To my very amateur eye (I’m a doctor, not a historian), Dr. Park’s most compelling contribution to the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is the impressive way he incorporates the voices of so many different kinds of people throughout the narrative of the saints. Thus, the history of polygamy is not just the history of Brigham Young, but the history of the women who variously lived in (and sometimes divorced from) polygamous families—women such as Emmaline B. Wells, Eliza R. Snow, and Fanny Stenhouse. The history of the Church during the progressive era is not simply a progression of prophets, but also the story of the intrepid and ultimately tragic Amy Brown Lyman (a progressive General Relief Society President whose prominent husband had an affair that eventually led to her removal from public leadership). And the Church’s most recent decades are populated by Gordon Hinckley and Russell Nelson, yes, but also by a whole host of characters who are, variously, Native People, Black, Brown, LGBT, feminist, and on and on. Here we have the stories not just of well-known church leaders, but also of Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Darius Gray, Ruffin Bridgeforth, Michael Quinn, Eugene England, Juanita Brooks, Carol Lynn Pearson, Ina Murri, Lester Bush, Sonia Johnson, Maxine Hanks, Sharlene Wells, Armaund Mauss, Gladys Knight, David Archuleta, Matt Easton, and many more.

None of these stories is entirely new, of course. As with a kaleidoscope, what most catches my eye is the degree to which Park has drawn together so many disparate parts. His book often feels like repeatedly shaking the kaleidoscope—watching as the multicolored crystals fall into unforeseen, surprising, and often striking constellations. Sometimes those permutations become heart-wrenching, and other times they form patterns both beautiful and complex. It is a testament to the degree to which Dr. Park gets out of the way of the story that it left me breathless at times from both wonder and sorrow.

To that point, what perhaps most impresses me about the book is that Dr. Park largely lets his subjects’ stories tell themselves. It is a truism that no narrator and no historian is without bias, perspective, or prejudice, and that remains the case in this book. Still, anyone who follows Park on social media knows that he has strongly held beliefs about what the Church has gotten right and what it has gotten wrong. It would have been easy enough to let his own political, cultural, and religious biases dictate the shape and arc of the narrative, either implicitly in the way he selects stories, presents events, and frames narratives, or explicitly in the way he summarizes through lines and brings together the grand “and here is the moral of the story” of such a sweeping chronology. Park, however, mostly avoids this pitfall. The book is nothing like a screed or a jeremiad. Instead, Park most often gets out of the way of his historical subjects, allowing them and their stories to speak for themselves.

I commend his restraint.

Still, that same rhetorical caution leaves other questions partly unaddressed. The book’s thesis—which it succeeds in demonstrating—is that the LDS faith (as well as that of other branches of Joseph Smith’s restorationist tree) grew into a fully formed religion in an exceptionally complex, often contradictory, and thoroughly paradoxical relationship with the nation that gave it birth. For example, this very American church espoused polygamy just at the time the U.S. was pursuing women’s suffrage—and then angered both conservatives and liberals by having those very polygamists fight for suffrage, too. The Church lauded the U.S. for its insistence on religious freedom even as it also was effectively driven from the country precisely because that religious tolerance could not yet then exist without bounds. And the nascent church angered its near neighbors in part because it insisted on a nearly-universalist eschatology as well as a presidential ticket that sought the eventual abolition of slavery even as the church tried to get itself off the ground in contested frontier territories where the “slave question” was very heatedly contested. Indeed, it will long remain one of the founding paradoxes of Mormonism that it sought so avidly for the acceptance of the country that drove the church from its borders and then, as Park demonstrates, finally achieved cultural acceptance right at the time the nation itself was (again, perhaps) fracturing. In fact, that the church eventually developed exclusionary policies against those of African descent stands in sorrowful relief against the fact that church members, too, were initially not considered “white” enough to gain full acceptance in a country built around reifying whiteness. This complex dance between the country and the church is perhaps the book’s most prominent theme.

Furthermore, and to some degree as a result of that very process of seeking national acceptance, Park demonstrates that the church has evolved profoundly over the two centuries of its existence. Indeed, the closest Park ever comes to a grand pronouncement of What it All Means centers on the nature of this process of theological, cultural, and ecclesiastical evolution. He writes, “One of the reasons the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has proved to be so resilient and successful is its ability to provide a narrative of continuity while constantly adapting to new circumstances. Religions thrive when they transform with time but still convince followers they never change.” This passage comes very nearly on the book’s last page and is framed as providing some explanation for the church’s striking success and longevity.

And that is all fair as far as it goes. But I say “as far as it goes” for at least two reasons. The first is that while the church’s ability to constantly evolve does seem a necessary prerequisite to its continued survival and growth, it nonetheless strikes me as an insufficient explanation. I would argue that the church’s unceasing evolution highlights and deepens the nature of that organizing question of what drives the church’s success.

After all, this is a church that started as an itinerant band of mostly ragged refugee believers—driven from town to town on the American frontier until finally being driven from the country entirely. Even after settling in the Great Basin, the saints did not achieve substantial national or cultural acceptance for another fifty, sixty, or seventy years. Indeed, during the decades spanning the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, the church was led by literal outlaws who often could not show their faces at public worship for fear of being taken into custody by federal marshals.

In the context of that continued adaptation, the church has had to change its approach to and often specific beliefs about things as wide-ranging as the nature of family and the relationship of citizens to the government. And yet, in the midst of the constant evolution and endless adaptation, and even after 200 years—the church is still here. Not only that, but this striking fact remains: the church has suffered from the ravages of rising secularism and postmodernity, yet it still provides refuge and haven for millions of people the world over. Indeed, even the many offshoot branches and conscientious objectors whose stories are outlined in the book stand as a testament to the continued cultural currency and theological power of the faith. That is to say: there is no need to push back against an organization that no longer wields any cultural or theological power.

This brings us back to that central question: why? At various times over almost two centuries—be that the death of the church’s founding prophet, the ceaseless branching of schism groups at multiple junctures, the abandonment of polygamy, or the vexations of modernity—it would have been easy enough, even expected, perhaps, for the church to either shatter or simply lose steam. And yet, millions of congregants the world over continue to find meaning and succor in this particular branch of the tree Joseph planted, even though many of them also count themselves as skeptics, doubters, iconoclasts, marginalized, and, in some cases, even outcasts.

How could this be?

In some sense, this is not a question that Park could ever satisfactorily answer. For one thing, such an answer exists outside the bounds of history and many of the answers would likely be unavoidably devotional or theological in a way that falls outside the purview of historical inquiry. Still, the closest he comes is in the epilogue’s final paragraph, where he writes, “Mormonism is an attempt to find facts in a world of fictions, certainty in a realm of distrust, belonging in a sphere of disunion, permanence in an age of transience, and longing to slay the demon of emptiness and confusion as if the adversary were reachable and could be killed.”

That answer speaks to me as deeply as anything in the book. It suggests—if never stating outright—that the genius of the restoration movement as it came to the world through Joseph Smith and his successors derives at least in part from the beauty and power of its theology. Park asserts—if only in guarded fashion—that it is the faith’s attempts to highlight the outlines of “facts, certainty, belonging, and permanence” that allows believers to hope that they will one day, together, “slay the demon of emptiness.”

And I believe that is probably right.

That said, I also believe that Park’s book shows—even if it never explicitly articulates—an even deeper, more resonant, and more paradoxical notion. Traditionally, church members have been wont to understand “church history” as the story of a succession of prophets and other prominent church leaders. But what Park’s book demonstrates so effectively is that the beauty in both the pattern of the fractal and the stilled chaos of a moment looking into a kaleidoscope is this: every pixel of the fractal matters, every jewel in the kaleidoscope sparkles. The beauty comes not from any single point in the picture, but rather in the complete image composed when all the pieces array themselves in just the kind of pattern a kaleidoscope alone can make.

This story might be true, and might simply be legend: when Laurel Thatcher Ulrich was asked why, as a feminist and scholar, she has stuck with a church that some see as patriarchal and sometimes inhospitable to academics, her puckish answer was to say, simply, “This church does not just belong to others, including leaders. This is my church, too.” And that is the paradox that animates the beating heart of Park’s book: the history of the church does not belong only to church leaders. The history Park outlines contains a cast of characters almost too numerous and myriad to count: here we find Eliza R. Snow—a vocal proponent of women’s suffrage who nonetheless testified with undying fervor to the moral necessity of the patriarchal order; here we have Amy Lyman Brown, tilting with and sometimes against church leaders as she sought to make the Relief Society into an organ of progressive reform; here we have Franklin Harris trying to make BYU into a Ivy of the West; here we have Juanita Brooks who tried doggedly to tell the truthful story of some very challenging parts of church history at a time when doing so was enough to earn her the ire and scorn of many faithful members; here we have Michael Quinn trying his best to live a life of integrity as a gay man who believed deeply and earnestly in a church where heteronormativity was the cultural norm and would eventually become a theological tentpole; and here we have Kris Irvin trying to make sense of being a person whose preferred pronoun was “they” in a church community where gender essentialism was taking on an increasingly central place of theological prominence.

While these people and many more like them have complex, nuanced, shifting, and sometimes even tragic relationships with the institutional church (some of them ended their lives outside the church’s official confines), what binds them together and tethers them to Park’s story is that the church mattered to them a great deal. However they navigated the complexities of their relationship to the church, they kept trying to find their place in all of this because something about the church’s restorationist theology spoke to the deep places of their souls.

And in that sense, there is something, for me, that is both theologically substantive and culturally aspirational about Park’s book. The institutional church’s history is complex, and so much of how we understand it arises from our own personal prisms and the lenses we bring to the case. But in the final analysis, my hope as a regular member is that we can eventually become a place where all of the people listed above—and many more—will feel welcome and safe here. Indeed, in that vein, Park’s book brings each of us to a place where deep Christian contemplation may be needed. The temptation will be to group the book’s characters into heroes and villains, and those groupings will likely fall along our own notions of who is helping and who is not. If I am liberal or heterodox, then I will see those of my same ilk as the heroes; if I am conservative and orthodox, I may have a very different list. But the miracle of the book is that it invites us to see that all of these characters have played an irreplaceable role. We are implicitly invited to look beyond our own sympathies and to consider what those who are different from us have contributed to the unfolding of the church’s history. Thus, we must strive together toward a day where we will be able to fully recognize that each of these players—and millions more like them—occupy unique and needed positions in the fractal, in the kaleidoscope. And that for all the complexity that is the church, those beautiful images that represent what we are when we are at our best can never be complete without every person who wants to belong.

To receive each new Tyler Johnson column by email, first subscribe to Wayfare and then click here to manage your subscription and select "On the Road to Jericho."