The Fleshiest Moments

What can Christ’s appearance to the Nephites teach us about our relationship to God?

William James writes at the conclusion of his Varieties of Religious Experience, “By being religious we establish ourselves in possession of ultimate reality at the only points at which reality is given us to guard.” For James’s philosophy of religion, the individual is the irreducible subject of consideration. Compared to texts, dogmas, creeds, institutions, and other “general messages to mankind,” the idiosyncrasies of our individual experience prove for James far more compelling. “Generalized objects,” James continues—things that exist beyond the individual––are “without solidity of life.” For this reason, James is also critical of abstract philosophical idealism in favor of naturalistic pragmatism. In his 1908 Hibbert Lectures, James explains further what animates his scholarship: “I am finite once for all, and all the categories of my sympathy are knit up with the finite world as such, and with things that have a history.”

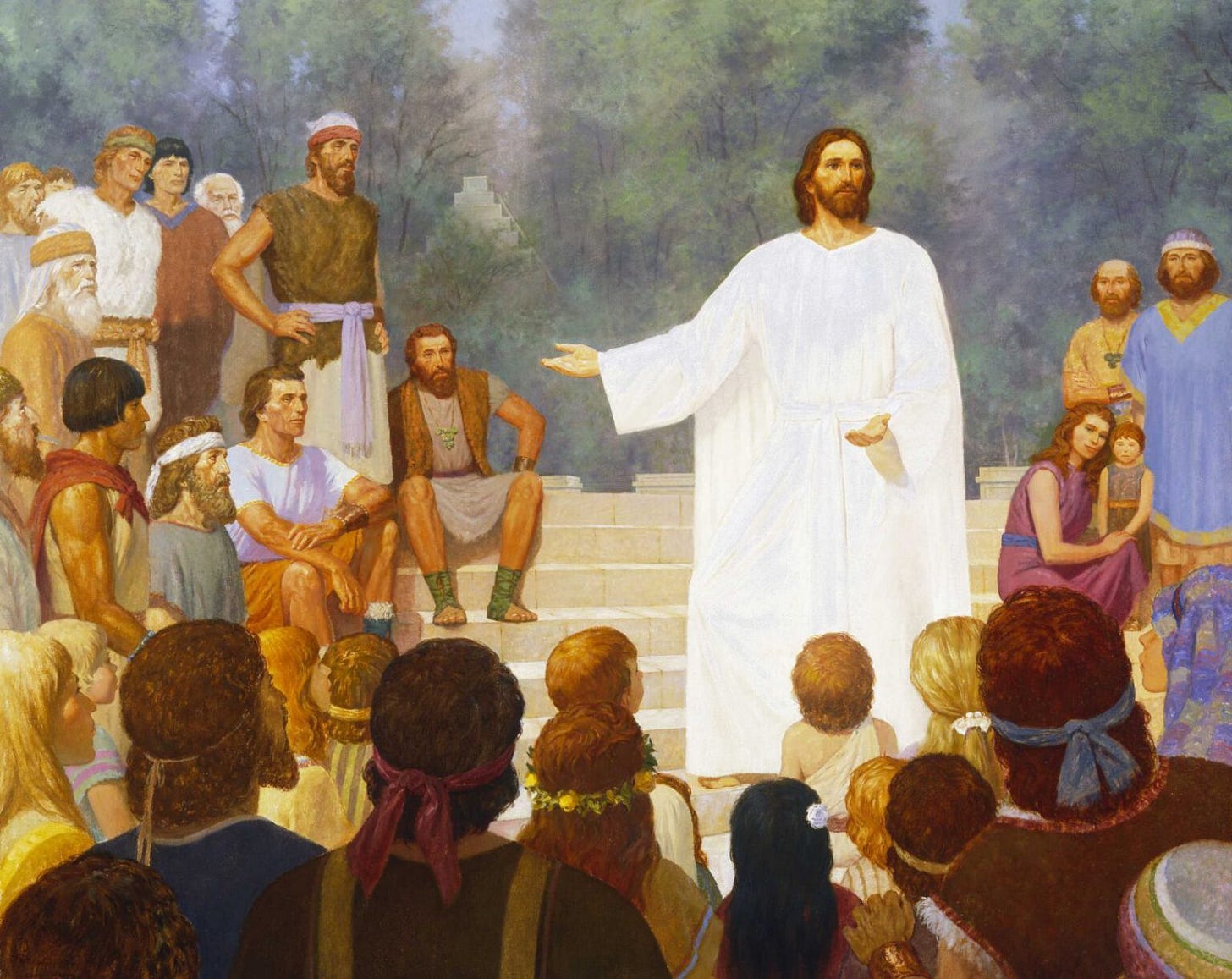

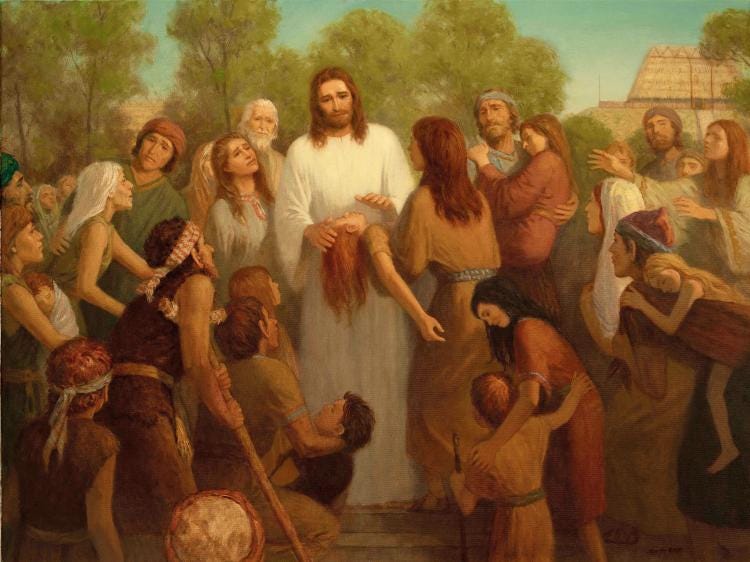

James’s confession of love for the ‘finite world as such’ resonates deeply with my reading of Christ’s visit to the Nephites in the Book of Mormon. I believe that God created the world out of love for us and a desire foremost to enter into relationship with us. Tracing back to the Cappadocian fathers and resonant with my faith as a Latter-day Saint, this explanation for why God created the world seems to suggest that the only way God could fully consummate his desire was incarnation. Emerging out of a faint, hard-to-decipher voice “as if it came out of heaven,” and materializing as an embodied, resurrected being who “stood in the midst of them” and then dwelling among us in the flesh are all essential to fully realize God’s love. It is in God’s divine economy of becoming “finite once for all,” to borrow James’s words, and “knit up…with things that have a history” that God’s self is fully realized and we can fully reconciled to God.

In 3 Nephi 11, the risen Christ invites the multitude to “arise and come forth” unto him and thrust their hands into his side, and feel the prints of the nails in his hands and his feet, so that they might know who he really is. The believing people whom the risen Christ visits anticipate in advance and thus witness prophecy fulfilled in his coming. It is for this reason that touching the imprints of Christ’s crucifixion one by one is followed with the promise that the people may know whom Christ claims to be, that, as Jesus says in the Gospel of John, “before Abraham was, I AM” (John 8:58).

In the Book of Mormon’s language, Christ’s preexistence is suggested in his promise that his audience “may know that [he is] the God of Israel, and the God of the whole earth, and [has] been slain for the sins of the world.” Upon Christ’s invitation, each individual is invited to come forth and encounter the divine hand-in-hand, flesh-to-flesh, and they “did see with their eyes and did feel with their hands, and did know of a surety and did bear record, that it was he, of whom it was written by the prophets, that should come.” This feeling and seeing is what I’ve decided to call the fleshiest moment.

Why is it important to me that Christ doesn’t merely appear but rather comes in the flesh to these people, that this scene be understood literally rather than symbolically, that they touch Jesus and did see with their eyes and feel with their hands? It has less to do with the event’s historical factuality, but its facticity: that Christ came to these people in a particular historical moment, who were themselves attached to a particular set of contingencies traced in the Book of Mormon’s narrative that these people had little control over, including an horrific account of catastrophic violence that befalls the Nephites in the chapters preceding Christ’s coming.

My contention is that Christ also comes to us today through our own fleshy experience in the world as such, in things which have a history. We encounter the divine in our poieses (plural) of the flesh. That each of our fleshiest moments—the things that render us utterly irreducible at times to our historical facticity and its material contexts—are precisely where God meets us in the here and now. It is within the fleshy and historical that God desires to enter into a relationship with us. Religion is one of these fleshy and historical poieses. As a Latter-day Saint, my faith’s highly controversial history of gold plates and angels and seer stones is one obvious dimension of the messiness of the flesh, but I’d like to speak to two bodily dimensions of my faith practice that help me find communion with God and through which I believe I see and touch Jesus.

Latter-day Saint Sunday worship services center around partaking of the flesh and blood of Christ through an ordinance (our technical term for formalistic ritual) we call ‘the Sacrament.’ By sanctifying bread torn into individual pieces and water served in individual cups, I believe I have the opportunity to come unto Christ each Sunday for a ‘fleshy moment’ of communion and atonement (at-one-ment), to thrust my hands into his wounds and experience an intimate encounter with the divine.

Another highly fleshly, if controversial, dimension of Mormon liturgical life is the practice of wearing what we call temple garments . In addition to our low-church Sunday worship meetings, we also practice temple rites, in which we make covenants with God and with each other that help us to enact holiness in our lives. By wearing temple garments I am encircled in the arms of God’s love at all times by virtue of my covenants.

The practice of wearing temple garments enacts on earth quite literally what is promised to the believer in the Book of Revelation: “He that overcometh, the same shall be clothed in white raiment” (Rev. 3:5). Paul also speaks to this promise in his second letter to the Corinthians: “For we know that if our earthly house of this tabernacle were dissolved, we have a building of God, a house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens. For in this do we groan, earnestly desiring to be clothed upon with our house which is from heaven: If it so be that being clothed we shall not be found naked” (2 Cor 5:1-3).

Wearing temple garments is a fleshly poiesis of these divine promises from Paul and John the Revelator, a token that audaciously suggests God will not forge a new creation in me in the distant future, but is at work here and now both in my body and in spite of my body and its weaknesses and shortcomings. This is why wearing temple garments is another way I come to see and touch Christ and why this more esoteric practice has deep spiritual resonance with me. In my encounters with Christ, as he draws me to higher and holier ground through the formation of sacred community with others, I find new resonance within the reality that’s mine to guard, to allude to the James quote I began with, with all its idiosyncrasies and historical contingencies.

This talk was originally delivered at Harvard Divinity School on September 25, 2024 as part of a Noon Service organized by HDS Mormonisms.

Kyle Belanger is a student at Harvard Divinity School and a recent BYU graduate in Classics and History from Anaheim, CA, with interests in history, politics, theology, and interfaith work.

Art by Gary Kapp.