After John goes to prison, his legend grows even larger. Everyone in Judea talks about him now: the workmen in the quarries who can’t help but think about his boldness every time they strike the unforgiving face of the rock, the visiting palace steward and his wife whose hushed tones at night and knowing glancing in daylight say he was right to question their king, the women in the brothels who feel both ashamed and encouraged by a prophet who believes that what has become acceptable for those with power matters less than what is right.

Though John has been shackled, the people hear his voice out of every link in their chains.

To the north, in Galilee, they’re also talking about him now. In the same towns where to mention John was a sure sign of religious excess a few months ago, his name leaps from lips to lips over shop counters, across public squares, around dinner tables. By being cast into prison, John has gained the same honor they give the prophet Jeremiah here: only John is alive, potent, and it’s impossible to know what God might do with his servant in the next instant. John has captured Galilee’s imagination, pulled it taut with long-suppressed desires for God’s hand to be so close again, for everything they’ve always proclaimed to believe to be true.

When Jesus returns to his home province, people want to see him because he has seen John. People want to touch him to feel some connection to their captive prophet. And when they hear he was baptized by John’s own hands, it’s hard for them to contain their excitement. Invitations come from this city and that for Jesus to preach in their congregations, and in his voice, it’s as if they can hear a little bit of John and it lights something deep inside of them on fire.

But the elders in Nazareth hesitate to invite him back home. Only a few people in town, of course, still remember the rumors about Jesus’ mother. Only a few ever whispered about how maybe Joseph had thought twice before marrying her. About how maybe there was some reason why so soon after the wedding he took her away and did not come back until they had a lot of happy kids who looked just like their father. And even the people who remember those old rumors didn’t exactly believe them, did they? Always treated Jesus as if there were no doubt whatsoever that he was Joseph’s own, never risked evil speaking by repeating unkind speculations.

But evil speaking is counted as a heavy sin for the way it nags and gnaws at the mind. Even after so many years, even without having spread any whispers or fully accepted them in the first place, the elders still feel uncomfortable when they hear or talk about Jesus. So they try not to talk about him, try to avoid the memory of old rumors that this new saint is Nazareth’s bastard son.

And it’s not until they’ve heard and heard from other towns how thrilling it is to hear from this native Nazarene, heard again and again how lucky their town is to count this man-who-John-baptized as one of its own, that the elders are able to push aside their hesitation and invite Mary’s son to address the congregation.

And so it is that on a somewhat-belated Sabbath, Jesus returns to Nazareth. He’s still thin, the elders notice, from his time in the desert, though they also notice that the new gauntness accentuates the penetrating gaze he’s had since he was young. When the time comes he rises to the scriptures and rests his hand on the passage, though he barely seems to look down at it as he calls out the words.

The Spirit of the Lord is on me, because he anointed me: to preach the gospel to the poor, to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, to recover the sight of the blind, to free from prison those bound in chains.

To tell you the year of the Lord has come.

Jesus breaks off mid-verse and rolls up the scroll, hands it back to the attendant, and goes to sit down. And even the old farmers who nod off through half the meeting have been elbowed awake now, because this is no ordinary passage, and no one wants to miss what he’ll say in commentary about the One who’s going to come, and about the days when everything is suddenly and drastically going to be changed.

The elders don’t even take their eyes off Jesus long enough to glance at each other. For a moment, the whole assembly seems to hold its breath waiting for words to emerge from that desert-thinned face, to see unveiled what’s going on behind those knowing eyes.

“This scripture is fulfilled before you today,” Jesus says.

And the words echo through the elders’ minds.

*

Here is something true: The imagination needs to be as strong as the heart, sometimes stronger, because while the heart sustains the body, the imagination sustains the soul. The baker imagines bread so that his hands can be moved to mix and knead dough, the young girl imagines a child and finds reason to prepare for marriage and motherhood, the carpenter imagines the rest his wares will bring before he spends his strength tearing into wood. The farmer imagines a hidden sea above the sky before he entrusts precious seeds to the drought-prone earth; he imagines a hidden sea beneath the soil before he risks his back to dig a well.

The watchman imagines the dawn to keep himself awake through the hour when the very last of his lamp’s oil is lapped up by the flame.

The elders of Nazareth are simple men, but they know how to imagine. Sacred words on tiny scrolls stand guard at their doors against the forces of evil. Every seventh day, a queen descends in her glory on their humble homes. Once a year, at least one of them goes up to Jerusalem with his body and down to Egypt with his soul to imagine living in his ancestors’ days, to remember how it feels to be ransomed.

When Jesus reads from the scriptures, the elders imagine John in his cell and their minds stretch back centuries to the days when prophets walked the land. And maybe the taut rope of their minds is enough to draw a portion of the power of those days back again. Maybe their raw belief can be the wick of a lamp that burns from bygone years.

But when Jesus speaks, when he asks them to stretch their minds back to the present and anchor their hopes on him, it’s as if they can feel something inside themselves break with a terrible snap.

It is agonizing to believe and believe until it seems your belief has reached the very end of the sky—and then be asked still for more so that your mind is forced all at once to turn back and wonder when it first began to believe too much, to hope too far.

*

The meeting is in an uproar. The elders should be working to keep the peace, but they don’t. Some are too outraged to want peace; others too heavy-hearted to stand and call for it.

And so no one restrains the people of Nazareth as they circle Jesus like the animals in the demon-haunted desert used to. “If you’re right,” the people say, “then let us see some miracles!” But Jesus doesn’t answer, just looks half-starved and weak as all the eyes in the room bore into him, looks so much smaller than he did when he read. “If you’re a great savior,” they say, “why haven’t you healed us?”

A man whose son was born blind spits in Jesus’ eye.

Another, whose herds have been plagued by a devil for years, reaches for Jesus to bind him with cords.

A few of the elders wonder again if they should step forward to stop the crowd until an old man rises and calls out to Jesus. “Think you’re special?” he says, clear and loud, “Then tell us, once and for all”—and though only a few catch the insinuation, an accusation concealed for years carries a special kind of poison—“Aren’t you Joseph’s son?”

So even the most moderate of the elders decide to leave Jesus to his fate. And it’s a woman who’s been sinned against and wronged from the time she was a little girl who walks out of the meeting house in search of the first stone.

When she returns, an argument breaks out. Some agree that Jesus the blasphemer should meet his death in a hail of rocks, while others say death should find him as he’s thrown headlong down the hill.

*

An important question: does justice live in books or in our hearts?

In either case, of course, it ends up in someone’s hands. In this case, in the hands of a village congregation whose hearts have just been pushed beyond what they can bear. But because these are thoughtful, God-fearing people, they pause a moment at the hilltop before taking action so that Jesus can speak from the Books in his defense.

“No prophet is accepted in his own country,” he tells them first, “and since no miracles happen without shared faith, I can’t help you.”

But when a physician fails, the people of Nazareth aren’t willing to assume the patient was to blame. They look for a steep spot to throw Jesus down.

“Why do you question God?” he says next. “Weren’t there plenty of widows in Israel when He sent Elijah to a foreigner in Zarephath? And what about Elisha: there were plenty of lepers in Israel, but God had him cleanse the Syrian, Naaman!”

But because anger is rarely interested in scriptural precedents, the villagers imagine the way his thin body will bounce off a distant outcropping of rock.

So Jesus stops trying to defend himself and simply walks away, walks away from the angry mob in a moment when, inexplicably, no one is watching him.

Years later someone who was there will remember the moment of confusion when they noticed Jesus was gone, will realize all at once with a sinking feeling that Jesus did work a miracle in Nazareth—that he made himself disappear.

*

After Nazareth, Jesus learns how to keep a secret. When he’s invited to read in other cities on the Sabbaths, he takes his passage from Hosea—I want mercy, not sacrifice—or from Joel—Put in your sickle, because the harvest is ripe—or from the Psalms—I will open my mouth in a parable, I will utter dark sayings of old—but avoids blatantly Messianic passages, especially from Isaiah. And when people ask in wonder what sort of person he is, he just shrugs.

It’s the secrets that make him famous in his own right. People can sense when they’re not being told something, and so now he’s not Jesus-who-was-baptized-by-John, but Jesus, mysterious saint. And it’s his name that begins to leap from lips to lips, carrying with it excited speculations, rumors, hushed tones of wonder and awe.

That’s when they begin to come to him. The wounded. The haunted. The ones who live off desperate hope alone. They don’t know exactly who he is and can’t explain to their own minds quite why they believe so fully that he can change them, but they come. Then they’ll follow him awhile, because when they see him talking with scholars or students about the scriptures, they don’t want to interrupt. And when they see him talking with respectable families, with elders or fathers or brothers or sons, they don’t dare approach him, don’t dare make their shame known. But sooner or later, the thin man finds a way to slip off for some time to think or pray in a quiet, solitary place. That’s when they build up their courage and walk up to him, when they open mouths which feel dry all at once to tell him why they have to see him, to tell him things aren’t all right, that they’re doing the best they can to go on but it’s hard, it’s very hard, and please. If he wants to, he can help them.

And whenever he looks at them, it’s like cool sweet water because the first miracle is that they feel for the first time in so long that they are understood. That he knows the shapes of the scars on their hearts, that they don’t have to excuse themselves for having come. Then he reaches out, and touches them: and their demons flee or their limbs gain sudden strength and their desperate hope transforms into wild, euphoric confidence. They want to shout and scream and dance all at once, but he pulls them aside and says: “Shhhh. Your faith has healed you—that’s all. There’s no need to mention me to anyone.”

But when they go back to their neighborhoods and people see the change and crowds gather round—of course they try to keep quiet, but when Jesus’ name is among the myriad hypotheses swirling around their ears, how can they help but say, “Yes! Yes! I don’t know who he is either, but it was him.”

*

Soon fame drives Jesus all the way to Capernaum on the lake’s shore, where people walk up to Jesus in the open, bringing their sick relatives or neighbors if they don’t need healing themselves. And he touches them and blesses them and talks with everyone as he heals, so that it’s not just the old man with fading vision but also the healthy granddaughter he leans on who comes away seeing the world anew. Very quickly, people notice, Jesus grows adept at maneuvering in a tangle of bodies. He avoids stepping on a person who’s been lain down behind him while he was attending to someone else; he’s expert at keeping his sharp elbows from crashing into bodies that crowd around his sides to watch what he does.

He seems equally adept at dodging questions. The scholars and students are eager to categorize him: is he simply a charismatic preacher, or a true tzaddik, a saint? Is he perhaps, another new prophet? Or an old prophet returned? But he never seems to answer their straight questions in straightforward ways, always seems to steer conversations sideways or upside-down instead, so that the students come out with new questions for their masters instead of answers.

One thing Jesus can’t seem to do, though, is find the quiet places in town like he used to. Between the persistence of those seeking relief from their diseases and those seeking relief for their curiosity, no alley is too remote, no roof too out-of-the-way and isolated for the thin man to slip away alone. Capernaum’s attention begins to weave itself around him like a basket until maybe the only way he sees to avoid being trapped under it is to get out of town: one evening, Jesus is still out on the streets teaching, healing, dodging, and then in the morning he’s gone.

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

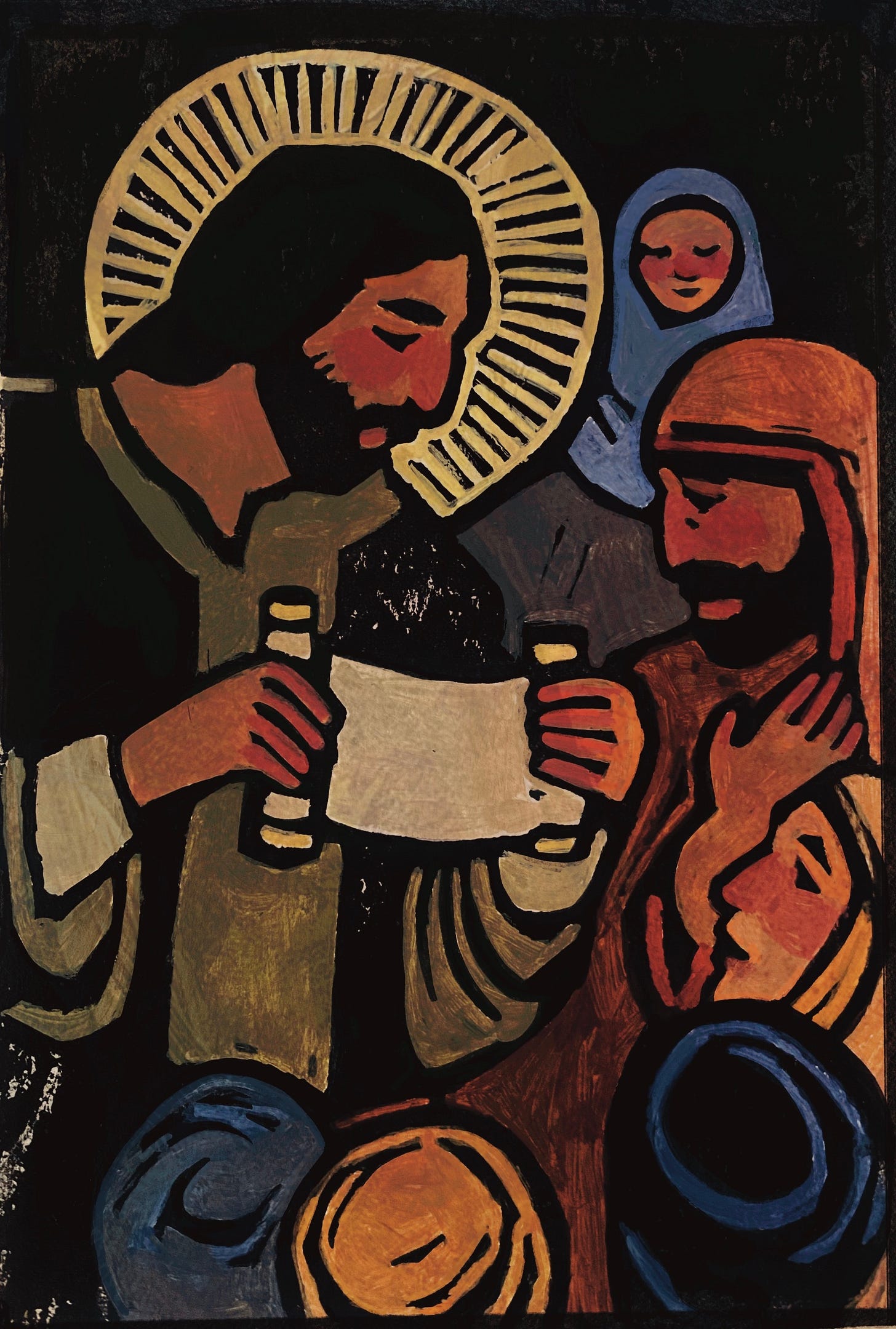

Original artwork by Sarah Hawkes.

To receive each new chapter of The Five Books of Jesus by email, first make sure to subscribe and then click here and select "The Five Books of Jesus."