Before Jesus sends out the seventy, he gives them a warning: they’ll be like sheep among wolves. They all nod gravely and brace themselves against dangers they vaguely imagine, but almost none of them really understand, because almost none of them have spent enough time alone out in the hills, as Jesus has, to see how wolves hunt.

So they imagine sharp teeth, but don’t think about wolves’ intelligence and patience. They imagine bristled hair and aggressive growls, but don’t realize that wolves hunt mostly by testing their prey for signs of fear and weakness, that wolves are most likely to bite animals only when they panic and run.

The seventy go out to preach. Where they’re successful, the twelve follow to heal. Since they’re met with few obvious signs of hostility, they forget all about wolves. But their enemies have not forgotten anything. Jesus’ critics have simply chosen to save the next confrontation for the right place and time.

*

Jesus and the apostles are exhausted when they arrive in one town late at night, but a crowd still gathers early the next morning, gaining size as quickly as the light grows with the rising sun. Matthew and Thomas are the first to wake, followed by Judas and Andrew, and the four of them herd the crowd out of the narrow street and into an open space where it’s easier to work. In the early morning cool, they bless the fevered. When James and John arrive, they move on to the lame. Next, they work to open ears clogged with infection, then, as more and more spectators begin to arrive, they command cataracts to fall away from the eyes of the blind.

Nothing about the morning has seemed unusual in the least by the time they get to the ragged father and his sleepy young son.

“Is one of you Jesus?” the ragged man asks Matthew.

“No,” says Matthew, “but he’s our Master. What can we do for you?”

“My son needs help,” says the man, and then he looks down like he’s nervous or embarrassed.

“Don’t worry,” says Matthew. “We’ll take care of him.”

So Matthew calls to Thomas and they look over the boy to find out what’s wrong. They find old scars, probably from being careless around a cooking fire, as boys often are. They find some dry, irritated patches on his skin, but no infection or fresh wounds. Other than being a bit sleepy, the boy seems alert. His vision and hearing seem fine, and his forehead feels normal.

“What exactly is the problem?” says Thomas. A few people watching seem disappointed and surprised, as if they’d believed that anyone working with Jesus should know everything without having to be told.

The father looks uncomfortable at the attention he’s getting from the crowd. “He’s not well,” he says curtly, and he looks hard at Matthew. “I thought you said you’d take care.”

Thomas is about to say something a little curt back, but Matthew speaks first: “We will. We may not be able to tell what’s wrong with him, but God can. And he’ll care for those who give him their trust.”

The man nods, and Matthew and Thomas move to bless the boy. But for the first time this morning, something feels wrong. When they put oil on his head, he starts to shy away. And when they try to touch him, he pulls away from them and stumbles back to his father.

“What’s wrong with him?” calls out someone from the crowd. “Are you healing the boy or hurting him?”

“He looked fine before they touched him,” says someone else and the boy claps his hands over his ears.

Matthew reaches toward the boy, but the father stops him. “It’s starting again,” he says, “it’s always like this when it starts.”

“What’s starting?” says Thomas. “Why won’t you tell us what’s wrong?”

Someone from the crowd snorts. “Isn’t it obvious?” he says, then he turns to the rest of the crowd and speaks as loudly as he can. “These frauds have put an evil spirit into him!”

Something about the speed with which the crowd focuses its attention on this new speaker reminds Matthew of nightmares he used to have, of his old terrifyingly plausible dreams of falling victim to mob violence. “We were only trying to help,” he says. “We are only trying to help.”

“Of course,” says the man in the crowd, half to the crowd and only half to Matthew. “I’m sure you’ve always been a very charitable person. Tell us: before you were with Jesus, what kind of work did you do?”

Matthew’s face flushes. He doesn’t say anything.

“Funny that you should mention that,” says another man. “I heard a rumor he used to be a tax collector.” People in the crowd glance at each other; apparently, that particular rumor hadn’t reached this town yet. “A generous one, though,” the man adds with mock sincerity, “they say all kinds of people were welcome in his house—especially after dark.”

Thomas steps forward. “Forget his past,” he says. “Let us help the boy.”

The first man raises his voice. “A bad tree can’t give good fruit,” he says to the crowd. “You all rushed here to get something sweet, but did you ask yourself first what sort of tree these men come from? Did you ask who they are or what they teach?”

A hush falls over the crowd. They look at the apostles with new eyes, and then down at themselves with an echo of Adam and Eve’s embarrassment.

Something about their sudden shame silences even Thomas, so it’s James who speaks up. “You’ve all seen us heal this morning. By this man’s own admission, if the fruit is good, doesn’t that mean the same for the tree? ”

The second man laughs. “You remind me of Pharaoh’s magicians!” he says. “So willing to use false miracles to fight against the authority of Moses and Aaron.”

“We honor the law and the priesthood as much as you do,” says James.

“Really?” says the first man. “Then perhaps you could explain a few of your Master’s teachings.”

And now James notices the trap, but it’s too late, because the scholars-in-disguise are already trying to tear them apart with a quick series of sharply pointed questions.

*

Matthew is still afraid his past will be an embarrassment and keeps quiet to avoid drawing attention to himself. Thomas still stings at how naive they made him sound and stays quiet. Andrew tries to remember what Jesus has said so he can respond as his Master would, but his tongue feels like it’s tied in knots too thick to let him get the answers out in words.

James and John have more of their mother’s warm temper than their father’s cool wisdom, so they forget that they’re fishermen who never quite managed to keep all the different prophets straight and fight for all they’re worth. But the two clever scholars draw them quickly into several self-contradictions, a few awkward admissions, and a misstatement about the law for which they could punished by a religious court.

As the scholars continue to tear apart the brothers’ credibility before a still-growing crowd, Judas slips off to wake Jesus and beg him to come help. That’s how he misses the talk about the end of the world.

“Do you think we’ll live to see a descendant of David back on the throne?” the first scholar says to James.

James wants to shout out that the answer is yes, wants to shake their shoulders as he tells them that this is exactly what they’re unwittingly opposing, but he isn’t a fool. He knows better than to waste his breath trying to piece together the puzzle of the kingdom of God with men like these anyway, and when there’s the possibility that they’ll turn him in to the king or the Romans and that his wasted breaths would also be some of his last, a direct answer is out of the question.

“I believe in the coming of the Messiah as much as anyone here,” James says.

“Of course you do, but when do you think he’ll come?” says the second scholar.

“I’m a fisherman,” says James. “If I want to know when it will rain, I don’t go around asking. I look at the sky. Is something wrong with your eyes that keeps you from doing your own looking?”

A few people in the crowd laugh at this, and James thinks maybe the tide will turn in his favor after all, but the scholars press on unfazed.

“What do you believe about the Prophet Moses foretold? The one whose words will be binding on the people. Will we live to see that Prophet?”

James sees an opportunity. He can’t tell them Jesus is the Messiah without exposing his Master to trouble with the Romans or the king, but he can tell those with ears to hear that the Messiah is close by talking about the Prophet. Since he’s not sure how much to say, though, he starts with a simple “yes.”

“Do you believe the Prophet has come already?” says the first scholar.

“Was John that Prophet?” says the second.

James hesitates. That makes sense—John must have been the Prophet. But is this another trap? If he says yes, will they report him to Herod?

Andrew speaks up before James can sort out the risks. “No, I was with John on the Jordan. He himself said he wasn’t.”

Now James is confused. His mother always told him the Prophet will come near the end of this world. And she taught him the Messiah will usher in a new one. So if Jesus is the Messiah, and John wasn’t the Prophet—

“Do you know who the Prophet is? Or how we’ll recognize him?” says the first scholar.

Now it’s John who speaks before James can make sense of what’s happening. “He’ll speak with authority,” he says, “not like you scholars do.”

The crowd laughs again, but James is less confident this time. He feels like he’s a little boy again and trying to prove his strength by swimming too far into the lake and nearly failing to make it back.

“That’s what drew me to Jesus,” says Thomas, as if he’s realizing something for the first time. “It was the way he spoke that made me want to follow him all night.”

The first scholar raises an eyebrow. “So you think your Master is the Prophet?” he says, “That’s strange, because I heard that he himself thinks he’s the Messiah.”

The whole crowd looks to the apostles and James gets a tight feeling in his chest. They’re cornered now, absolutely stuck. They can’t back down from what Thomas said. They can’t deny the scholar’s accusation about their Master’s claims, because they’ve heard how Jesus reads Isaiah and seen how he speaks of David. Saying nothing isn’t much of any option at this point because it will make the crowd assume, somewhat accurately, that Jesus’ closest followers are spectacularly confused. On the other hand, it’s hard to come up with a good answer when you know one wrong word could land you in prison and that another could wake the violence that can so easily erupt out of a crowd this size.

James startles when he hears Jesus’ voice behind him. “What is all this questioning about?” Jesus says.

For a moment, both scholars and apostles hesitate, each searching for words that will give their side the advantage. But before anyone comes up with anything, the ragged father speaks.

“I brought my son to you for healing,” he says. “But your men couldn’t help. I just want someone to save my boy.”

“We were asking when you think the signs of the End will come,” says the second scholar. But Jesus just mutters, “how long will I have to live with this shallow and faithless generation?” as he pushes past the scholars toward the boy.

The ragged man’s son is picking at his clothes and hardly seems to notice Jesus approaching. Then he looks up at Jesus and moans loudly as he collapses, unconscious, to the ground and begins flailing wildly, spit dribbling out of the corner of his mouth.

Jesus rolls the boy onto his side. “How long has this been happening?” he says to the father.

“Since he was very young,” says the man. “Sometimes the spirit tries to throw him in the fire or drown him.”

Matthew understands the man’s earlier silence now—he was ashamed to admit the nature of his son’s affliction.

“Please,” the man says to Jesus, “if there’s anything you can do, have compassion and help us!”

Jesus looks at him: “I can help if you can believe,” he says.

The father looks ashamed again but forces himself not to look away. “Lord,” he says, “I believe.” He looks down at his convulsing son. “Help my unbelief!”

The boy’s limbs are thrashing around and a few people in the crowd, still alarmed by the scholars’ suggestion that they’ve given their trust to a wicked man or a fraud, are about to pull Jesus away from the boy when Jesus commands the evil spirit to go out.

Peter has just arrived on the edge of the crowd when he hears the spirit’s angry cry: “You Son of God!” Some in the crowd wince at hearing the spirit blaspheme; others ask what the spirit just said, though of course no one will take the name of God in vain to repeat it to them.

But the murmured questions stop abruptly, and a cold hush falls over the crowd as people catch sight of the boy’s still body, robbed even of the motion of breath and his face as pale as death.

*

It’s one of the scholars who breaks the silence. “He’s dead!” the man shouts, and he glares at Jesus in unmasked accusation.

And if they’d known and loved the boy, if he’d been a prominent villager’s heir, Jesus might have been killed then, might have been stoned as a lowly murderer at the hands of the same people who’d come to him that very morning for help. But few are willing to seek sudden and violent justice on behalf of a poor stranger, and so the man’s son is left unavenged.

“Do you believe?” says Jesus to the father.

“Anything,” says the father back to him.

So Jesus takes the boy by the hand and lifts him up. Color returns to the boy’s face and his eyes are clear as he looks at his father and embraces him.

The people in the crowd don’t know whether they should be filled with terror or with joy. Their minds are stuck, unable to reconcile the moment when they thought Jesus had killed a boy with the moment when he seemed to raise him from the dead.

No one says anything. All of them—the sick and the seekers, the scholars and the apostles, the son and the father and Jesus himself—just turn away and walk home.

*

Back in the house, Thomas has a question for Jesus: “Why couldn’t we heal him?”

“You can only cast that kind out through prayer,” says Jesus.

No one dares to ask the next question: if prayer is required to cast out that kind of spirit, why did Jesus simply act? Why didn’t he have to pray?

*

In the unusual quiet of that afternoon, Peter, James, and John sit together behind the house.

“Who do you think he is?” says James.

“I don’t know,” says Peter. He thinks about what the evil spirit said, what they’ve been saying every time. He knows it’s blasphemous to believe what he is beginning to believe—for who in heaven can be compared with the Lord, who among the sons of the mighty can be likened to Him?—but he can’t see any other explanation.

“Do you remember the storm on the lake?” says John, and they don’t have to tell him they do. Then John sings, “O Lord God of hosts, who has strength like Yours? You are strong and Your faithfulness surrounds You. You rule over winds and the rage of the sea: when its waves rise like mountains, You can calm them.”

Peter shudders. There’s no going back now. There’s no going back.

*

That night, seven of the seventy come and tell Jesus about how they’ve cast out evil spirits in his name. The twelve don’t mention how their day has been.

Jesus reminds the seven about how the Lord led their ancestors through a vast and dangerous desert, filled with fiery snakes and scorpions. “Sons of Eve,” he says, “I give you power over them. Wherever you walk, nothing will harm you.”

That night, Jesus breaks bread with his hosts and his guests while Mary goes out to buy new wine. The seven tell about the villages and towns where they’ve been. The twelve finally gather the courage to share the story of their failure, and finally tell Jesus about the debate he interrupted. James asks what they should say to people who ask specific questions about the Messiah, the Prophet, and the coming Day of Judgment, but Jesus’ only response is that he’s grateful to his Father that the wisdom of the wise has perished, and the understanding of the prudent has been hidden.

That night, in another house, the scholars also sit down to dinner. Their host is a prominent supporter and advisor of Herod—someone they wouldn’t ordinarily count as a friend—but tonight they share his bread and the corners of their mouths become red with his old wine. They drink and they talk: about conditions in the country these days, about the king’s health. They talk and they drink, toasting the king’s current trip abroad, circling closer and closer now to the thing that has brought them together, until at last they arrive at the fundamental point.

“We can handle his followers,” they say, “but if this movement is going to be brought under control before there’s serious trouble, we need your people to stop Jesus.”

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

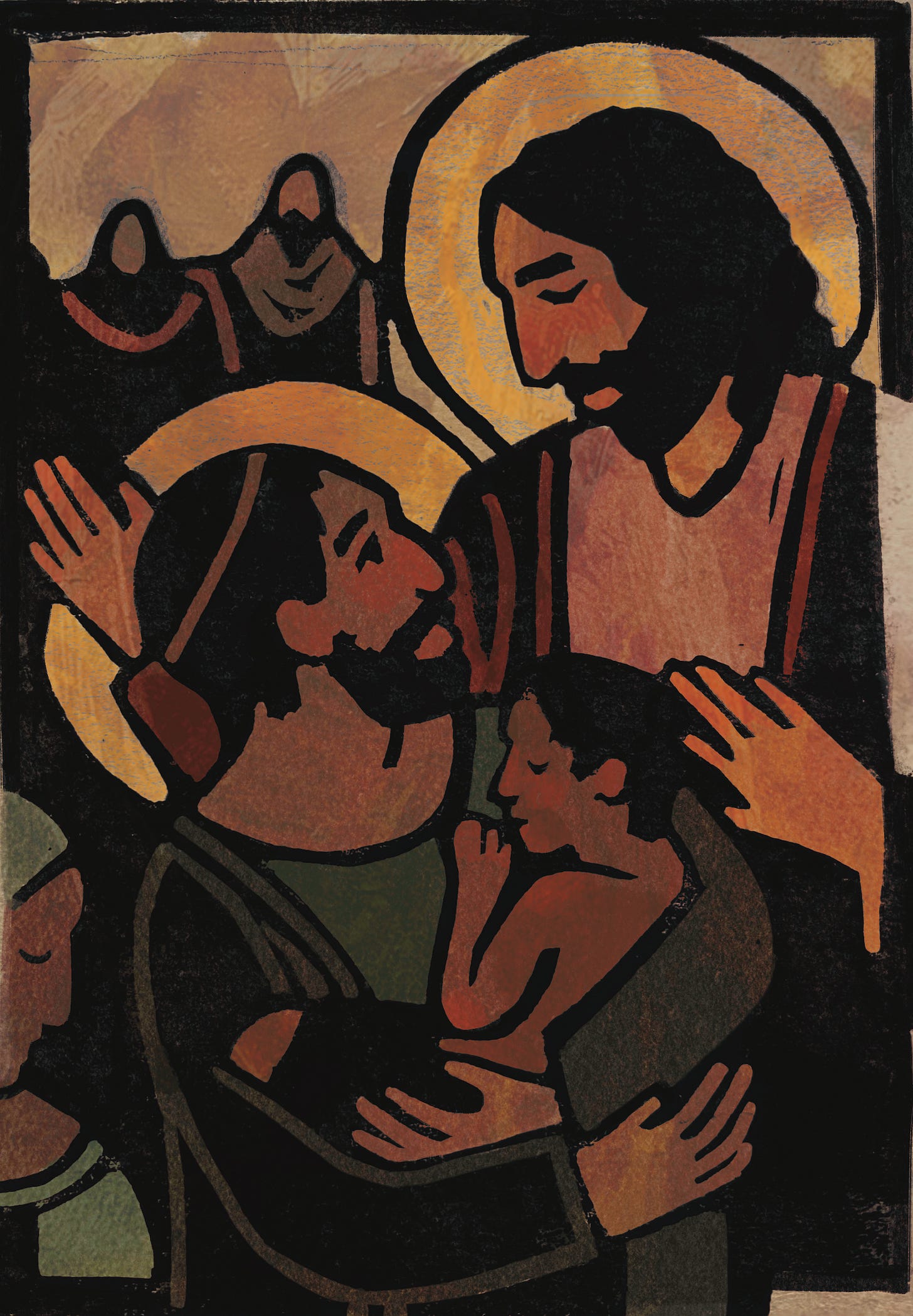

Original artwork by Sarah Hawkes.

To receive each new chapter of The Five Books of Jesus by email, first make sure to subscribe, then click here and select "The Five Books of Jesus."