The AntiChrist Is Hiding Inside Your Smart Fridge

A Review of Paul Kingsnorth's "Against the Machine"

In his 2025 book, Against the Machine, Paul Kingsnorth’s enemy is no less than the Antichrist. But Kingsnorth, to use the words of another Paul, “wrestle[s] not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, and against spiritual wickedness in high places.” For Kingsnorth, the Antichrist is not a political leader or even a person, but instead the Machine, a system that includes progress, modernity, and the accelerating growth of technology. The Machine’s body is the network of roads and internet cables and electrical wires crisscrossing the globe, but it is ultimately a system, one that began with the enclosure of the commons and that has increasingly enclosed more and more aspects of human life. It feeds on culture, human independence, and communities, leaving behind a homogenized, flattened, bland, spiritually-dead society. These are bold proclamations, and Kingsnorth’s diagnoses deserve serious deliberation.

The book unfolds over four parts. The first part outlines a perhaps rose-colored view of a pre-Machine pastoral past where people enjoyed, in the words of Rector of Cookham, Berkshire, “comfortable . . . partial independence”—an independence that has now been replaced with “the precarious condition of mere hirelings” (46). The general thrust of this section is that, while we may have been peasants, the powers that be largely left us alone to do as we would, to survive from the sweat of our brow, to have community with man and communion with God.

The second part of the book looks at how the Machine has unraveled that community and communion: the enclosure of the commons, imperialism wreaking havoc on the wider world, and the rise of technology. In modernity, in contrast to our ancestors, we are now dependent on a consumerist and capitalist system that, if it were to collapse, would leave us with little to nothing. We would not have the skills, neighbors, or faith to support ourselves. Kingsnorth explains:

A city’s inhabitants are dependents: they have neither the space, the skills, the time nor the inclination to fend for themselves. A city dweller exists to serve the city. If she is lucky, the city will also serve her. If she is unlucky, she will end up juggling three jobs and trying to scrabble together enough pennies to feed her children. The city provides opportunities for wealth that the village never could, but it treats its poor and marginalised with a contempt that the village would regard with incomprehension. (84)

Kingsnorth turns to Lewis Mumford for further support: “In city culture . . ., ‘every aspect of life must be brought under control: controlled weather, controlled movement, controlled association, controlled production, controlled prices, controlled fantasy, controlled ideas,’” with its ultimate end “‘to accelerate the process of mechanical control itself’” (86).

At the root of this desire for control is an effort to separate ourselves from nature, community, and God; to somehow wrest control from every other force in the universe and invest it only in the individual. We see this control in the sterilization of human spaces, the presumption that the complexity of human consciousness is collapsible to mere computing power, the hubris that we can manage every aspect of human existence through big data and monitoring and nudge psychology, and the desire of our elites to bring about the singularity, the uploading of our consciousness into a computational cloud. Kingsnorth sums up this view: “[I]f a machine is the metaphor you use to represent other living beings, then a machine is what you will make of the world” (69). These two forms of control—the investment of all meaning and ostensible control in the individual on the one hand and big data and government on the other—might seem at odds at first, but the former is a false truth sold by the latter as a way of atomizing us and thus enabling the Machine to control everything. Like a fish stranding itself upon the beaches of modernity’s hyperindividualism, to separate ourselves from nature and community and God—the very waters in which we swim—is death.

The third part of Kingsnorth’s text examines the outcomes of the Machine: the consumption and homogenization of culture, the uprooting of people from places, and the destruction of history and common story. We see this homogenization as we drive across the country, where more and more towns look like Strip Mall USA, lacking individuality or unique feel. We hear this homogenization as regional diction and dialects fall away. The apex of America’s Machine culture (though Kingsnorth writes primarily of the United Kingdom) seems to be Buc-ee’s and McDonalds and your favorite YouTuber, which is to say, culture has become where and what we consume, not where and how we commune. Kingsnorth turns for support here to psychiatrist, philosopher, and neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist: “‘[W]e no longer live in the presence of the world, but rather in a representation of it.’ There is no territory in this new world, only map” (267). We are no longer rooted in any common past, people, place, or prayer (that is, faith). Instead we are atomized individuals, cast adrift.

At the end of part three, Kingsnorth unveils the Machine, first as Progress—which calls to mind Edward Abbey’s observation that “growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell”—then as the rise of technology, before finally pulling back the curtain to reveal the Antichrist. That is to say, the Machine is not just a cultural or political or philosophical ill—it is a spiritual malevolence. And battling a spiritual monster requires a spiritual core.

Kingsnorth turns to ways we can combat the Machine in the fourth part: reactionary radicalism in the spirit of the Luddites and escaping the reach of the state through askesis (self-control or self-discipline, sharing a root with the word ‘asceticism’). Kingsnorth clarifies the Luddites’ position on technology: they were not opposed to it, but, quoting Craig Calhoun, campaigned “for the right of craft control over trade, the right to a decent livelihood, for local autonomy, and for the application of improved technology to the common good. Machinery was at issue because it specifically interfered with these values” (280-81). Technology should support the moral economy instead of destroy it. This view echoes that of Ivan Illich’s Tools for Conviviality, which generally asserts that technologies and tools should be adopted to the extent they further human capability, not replace it. The former empowers human thriving while the latter diminishes human independence. Choosing which technology we adopt is, in essence, another form of the self-control Kingsnorth calls for. Indeed, while he sometimes comes close to calling for revolution—for escaping the state and starting new civilizations—he ultimately comes home to being rooted in one place, to choosing technological boundaries one won’t cross, to living close to nature, and to seeking God.

Kingsnorth is at his best when diagnosing problems and breaking down traditional battle lines. The battle isn’t between right and left or us and them. Instead, the left and the right both ultimately serve the Machine, and the real battle is between us and the system that is the Machine. Kingsnorth also astutely argues for balance between two extremes. He asserts that we should cultivate, not disavow, national culture and heritage, but cautions that these can also tip into rabid nationalism and xenophobia. Extremism also serves only the Machine. And he’s correct that there is something sickly and wrong with our consumerist, extractionist society, something that goes beyond each generation’s main character belief that theirs is the greatest crisis. That wrongness goes beyond political division and the twisting of religion to the aims of power and the overreach of government (things that have always been with us in some respect). Today, those aspects coincide with screen addiction, artificial intelligence (not to mention its accompanying insatiable energy use), the push towards transhumanism, the increasing destruction of the planet, the loss of community, and a general detachment from nature and the world and God. These societal and environmental ills call to mind EO Wilson’s observation that, “[w]e have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions and godlike technology. And it is terrifically dangerous, and it is now approaching a point of crisis overall.” While Wilson advocated for furthering our pursuit of science and technology, the real problem almost certainly lies with our Paleolithic emotions, something that transhumanism and artificial intelligence will not solve. Indeed, screen addiction and artificial intelligence will likely only hasten us spiraling down the drain (or at best reduce us to animals living in a world of machines). Kingsnorth is right to sound the alarm.

But the book also has serious weaknesses. Primary among those weaknesses is the depth of his inquiry. He covers hundreds of years of history and social movements and flies over the whole of modernity and in doing so can only cover the surface levels. But some aspects deserve far more scrutiny. For example, he mentions the love of money. And while that root of all evil undergirds the consumerism and capitalism he criticizes, he doesn’t unpack and examine that aspect of modernity. Many, myself included, see the love of money as one of the keys to understanding our current predicament: it doesn’t just undergird consumerism and capitalism but also explains, at least in part, the quantification and reduction of the world, the transformation of humans and plants and animals into numbers valued only for their economic and measurable output. Indeed, the atomization of individuals is also the atomization of all things: if something cannot be measured, it cannot be controlled; if something is ineffable, it cannot be captured. This already begins to respond more fully to that desire for mechanistic control discussed above, and it’s worth delving into more fully. To his credit, Kingsnorth invokes an array of writers and thinkers who have considered these issues more fully, many of whom have also explored more deeply ways to begin reorienting ourselves: Wendell Berry, Marshall McLuhan, Simone Weil, Jaques Ellul, Christopher Lasch, Augusto Del Noce, Iain McGilchrist, Rupert Sheldrake, Lewis Mumford, and others. At very least, shining further light on these writers is a worthy and generous service and we would do well to read and respond to more of them.

Another weakness is that Kingsnorth’s argument collapses to some degree under its own weight. By naming technology, progress, and our current societal systems as the Antichrist, he creates a zero-sum game. If these things truly are the Antichrist, then we should be fighting them tooth and nail. We should go further than the Luddites. We should drive stakes through our cellphones and pile our computers and books in a bonfire; we should rid ourselves of science and learning and hold in higher esteem societies that have done similarly. But I don’t believe that violent revolution marks the way through. And Kingsnorth more or less admits the same as he ultimately asks us only to consider limits we should place on our own technology use and exhorts us to look to nature, community, and God, each of us finding our own way. I agree, but that’s far less provocative than calling an amorphous metaphor the Antichrist. As noted above, others have dived far deeper into how we should proceed. As just one example, Ivan Illich’s Tools for Conviviality directly addresses how we should select the technology we use in our lives and communities. He suggests asking two questions: (1) Does this tool further my independence or diminish my skills (and thus create dependence), and (2) Does this tool bring me into greater community with my fellow man and God? That inquiry—which ultimately dives far deeper than just a two-question outline—already goes further than Kingsnorth.

Kingsnorth is perhaps tired. And that’s fair. He’s been waging war against the Machine for decades now, as well-documented in his other books and on his Substack. Perhaps that’s why Against the Machine often reads as a series of essays stitched together with a thick piece of yarn. The threadwork can be loose and the patches repetitive, and he occasionally resorts to caricatures and grand, sweeping statements about his targets. Those aspects of his writing can undermine the seriousness of his topic, but he’s very serious and he hits home with too many points to dismiss what is ultimately important work. He just struggles to stick the landing. In many ways, both explicit and implicit, he leaves the work to us.

Where, then, are we to go? Where is the synthesis? One aspect that Kingsnorth overlooks in his survey of Western history and the rise of the Machine is Christianity’s role in developing technology. Indeed, according to David Noble in The Religion of Technology, technology and science have always been a project of Christianity, with the child (technology) attempting to kill the father (religion) only in the last few decades. Noble’s book traces Christianity’s technological and scientific endeavors from the close of the first millennium after Christ, when Johannes Scotus Erigena posited that the artes mechanicae (or technology) had a role in the redemption of man, that they were in fact “man’s links with the Divine, their cultivation a means to salvation.” Erigena’s assertion broke the seal on a zeitgeist that had previously viewed technology as only pertaining to the world of fallen man.

Depending on how you read “their cultivation a means to salvation,” Erigena’s view could contain the seeds of the Machine—the potential to build a modern tower of Babel, replacing God’s salvation with our own cybernetic arm of flesh and metal—or it could provide a synthesis that somehow derailed somewhere along the way and needs redirection to get back on track. Restoration theology may provide the map.

Section 131 of the Doctrine and Covenants asserts that the immanent and the transcendent have always occupied the same plane. “All spirit is matter, but is more fine or pure.” Combined with the King Follett discourse and LDS views of theosis, LDS believers are perhaps one of the religious groups most likely to accept Arthur C. Clarke’s Third Law: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic [or the power of God].” Theosis is a process (enabled by God as a gift to God’s children) and heaven and earth exist in the same realm. While God does not appear to call us to bring about theosis ourselves via technology, God does call us to build Zion, a precursor or step closer to heaven, where there are no poor among us, where we dwell in righteousness, and where we are of one heart and one mind.

The call then is to refine and purify. Not only ourselves, but our world, our systems, our technology, such that it helps us in our quest for Zion, which means using technology in a way so as to eliminate poverty, dwell in righteousness, and be of one heart and one mind. We can employ frameworks, like Illich’s inquiry, to discern between the ways we might use a technology virtuously or viciously; we can circumscribe all truth—both the immanent and the transcendent—into a great whole; we can refine all things in an eternal round (that is, in an eternal process). This is a call to build instead of retreat, to lean into what is happening and take an active role instead of leaning away from and passively watching the world pass by. It is a call to tend to the world in a process of repentance and change. Processes also require refining, and all of this requires work.

The revelation of truth may also be a process. As Iain McGilchrist says in his magnum opus, The Matter With Things, “I think it possible that some of the disagreements in the debate about truth start with these broad differences in whether we see ‘truth-as-correctness,’ a thing that can be determined, and into which nothing of us enters; or ‘truth-as-unconcealing,’ a process of something revealing itself to us only through our experience” (386). Truth as process, restoration as process, progress as process, technology as process, human experience as process, Atonement as infinite and everlasting process.

LDS theology responds to Kingsnorth in one other important place. While Kingsnorth insists that we need to tell new stories, he consistently looks to the past, to the Garden of Eden as a pre-Fall paradise (indeed, he starts the book there). But Eden was always a garden, and gardens always require tending, pruning, work. Furthermore, as LDS theology posits, to leave the garden was to progress as God wanted us to progress, to learn by our own experience to distinguish between good and evil. So yes, let us heed Kingsnorth’s warning about the evils that have emerged. Let us also heed his call to commune more with each other, with nature, with God. But let us also not disengage from the process and from true progress. Instead, let us ask, is this technology Babel and the arm of cybernetic flesh, or will it help us to build Zion? And then let us go and build Zion. Let us tend and prune and water the garden before us instead of longing to return to the one we left long ago.

Consider this book review in the context of Duncan Reyburn’s review of the same volume.

Ryan Fairchild is an entertainment and technology lawyer, father of three, and husband to the supremely talented Angelyn Otteson Fairchild.

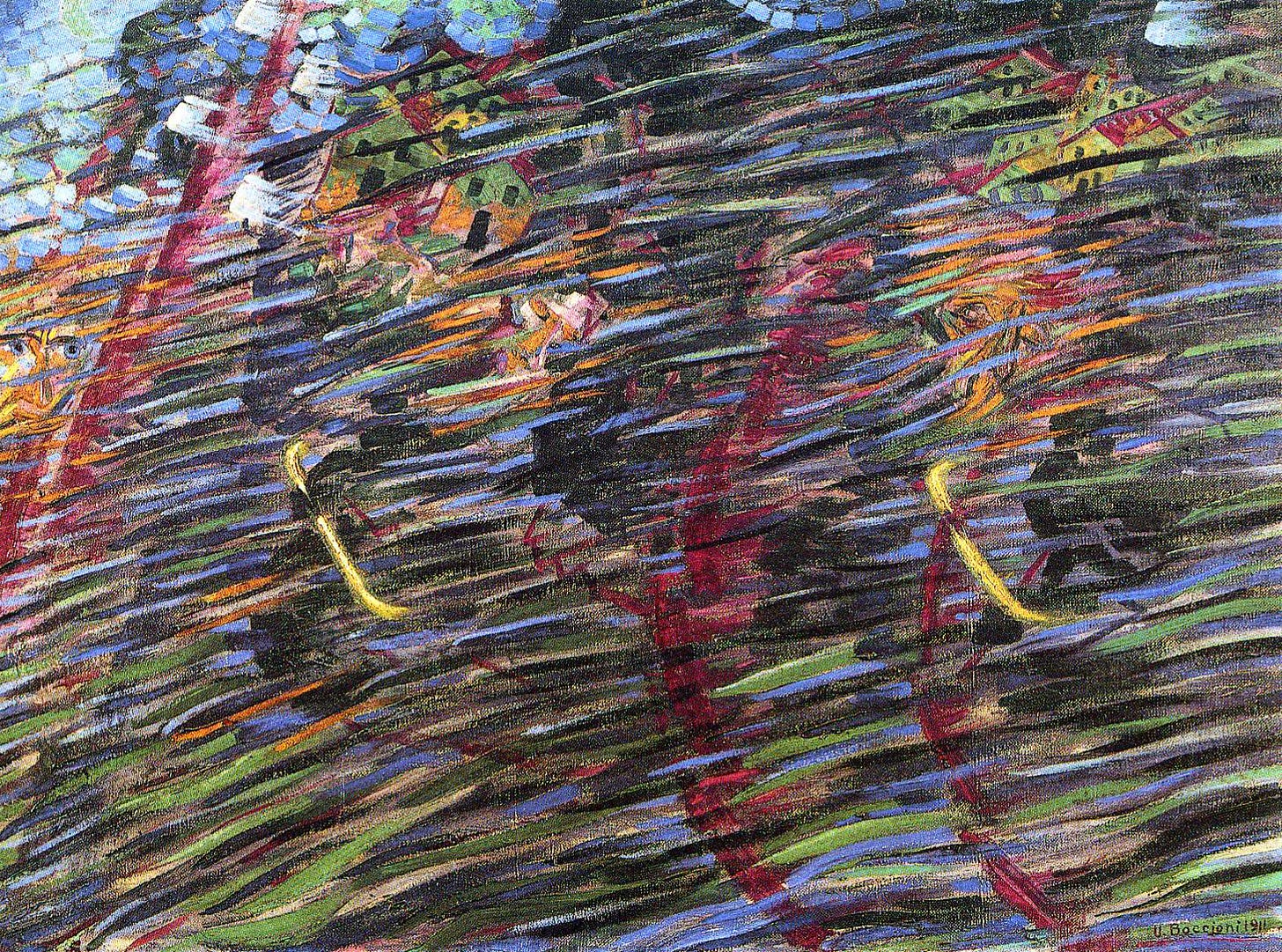

Art by Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916).

Please enjoy another review of Against the Machine published by Wayfare author Duncan Reyburn.

Choosing God or the Machine

Most of us are entirely unprepared for what has already happened. This may sound more paradoxical than it is. Understanding, after all, always arrives late to the party. All of us were born into a world already on the go, and it often takes us a while to catch up. Still, if there were ever a moment to self-locate and make some changes, this is it. We ha…

Interesting perspective, Ryan, thank you.