As part of his ubiquitous Book of Mormon series, Arnold Friberg’s painting of the brother of Jared (Fig. 1) has defined the way generations of members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints visualize the scene in Ether 3. You may even have heard the anecdote about how Hollywood filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille was so taken with the image that he hired Friberg as artistic designer for The Ten Commandments film (resulting in clear similarities between the painting and DeMille’s scene of Moses at the burning bush). But many other artists have also depicted the brother of Jared, and sometimes in quite different ways. So why is this the portrayal that’s most familiar? What was the earliest depiction of the brother of Jared? Are there many images of him that preceded Friberg’s? What images have been created recently? How much have these images been used in Church media or other published sources? In what ways has Friberg’s painting influenced how other artists have approached the scene?

The Book of Mormon Art Catalog provides comprehensive answers to these kinds of questions for the first time. Grant funding from the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship and the Laura F. Willes Center for Book of Mormon Studies enables the catalog to be offered online, free for everyone. With more than 2,500 images, and new pieces added constantly, the database is the largest catalog of Book of Mormon visual art and is a resource for scholars, artists, teachers, and members of the Church. More than just a list of images, the catalog provides details about each piece, including information on the artist, the scripture reference, the style and technique, and its inclusion in exhibitions and published sources. This data allows users to create custom searches and discover lesser-known artworks as well as analyze broader trends in Latter-day Saint religious art.

Using the brother of Jared as a case study, this essay will briefly model some of the possible uses of the catalog. For instance, the catalog entry on Friberg’s painting lists its appearances in Church media, which includes Church magazines, the printed Gospel Art Book, the online Gospel Media Library, the Church History Museum Store Catalog, the 2020 Come, Follow Me manual, and the Church Facilities Artwork Catalog. The entry also notes that the painting is on view at the Conference Center in Salt Lake City. It’s little wonder, then, that this painting is so familiar to most Church members. But how does it compare to other illustrations of the scripture?

A quick search of the catalog using the “Topics” filter reveals that there are 95 known artworks of the brother of Jared, his shining stones, or his voyage across the sea. Only two depictions pre-date Friberg. The first was done by John Held Sr. and published in 1888 in The Story of the Book of Mormon (Fig. 2). The style of Held’s piece is decidedly nineteenth-century and not at all like Friberg’s. Drawing on traditional European religious art, Held depicts Christ with short dark hair and a beard, dressed in a white toga, floating above the ground, and marked with a halo. Tropical foliage and palm trees indicate the Near Eastern setting. The focus of the image is on the towering figure of Christ rather than the small, kneeling figure of the brother of Jared who is turned away from the viewer. Overall, Held’s image feels more static and more like a stage-play, whereas Friberg’s painting employs a dramatic viewing angle and greater movement. If Friberg was aware of the 1888 image, he certainly didn’t feel beholden to its precedent.

The other earlier image comes from a series of comics by John Philip Dalby based on the Book of Mormon that was published in the Deseret News from 1947 to about 1953. The earliest scenes in the series show the brother of Jared kneeling before a pile of glowing stones touched by the finger of the Lord (without showing the full body). Perhaps Friberg, who used a similar composition, was influenced by these drawings. Friberg’s painting would, in turn, affect many of the depictions that came after it.

Other than a series of 26 comic-book style illustrations by Robert Barrett in the 1985 edition of Book of Mormon Stories published by the Church, there are only five known images of the brother of Jared made in the second half of the twentieth century. The most reproduced of Barrett’s illustrations, Brother of Jared Sees the Finger of the Lord (Fig. 3), is clearly patterned on Friberg’s painting. The composition is identical: on the left, a man clad in a fur tunic, turban, sandals, and forearm bands raises his hand in surprise and, on the right, the finger of God (the full figure of deity being carefully concealed) touches the glowing stones. Both the Barrett illustration and the Friberg painting were originally intended specifically to help children learn the scriptures. But because of their widespread use in Church media across the board, they were also the only images of the brother of Jared familiar to most adults for many years.

In the first two decades of the twenty-first century, many artists created images of the brother of Jared, but it doesn’t appear that any were published in Church media until the 2020 Come, Follow Me manual, which included a 2001 painting by Marcus Vincent, a 2012 painting by Jonathan Arthur Clarke, and a painting by Gary Ernest Smith. The inclusion of these and other artworks in the Come, Follow Me manuals indicates that the Church has begun to use a greater variety of imagery in its publications. And while a few more works of art joined the Friberg painting and the Barrett Illustration patterned after it, artists around the world were engaging with these scriptures and coming up with their own visualizations.

One of these pieces is by Gary Evan Polacca, a great-grandson of the famous Hopi potter Nampeyo. In his carved and painted clay pot from 1994, he uses traditional Hopi design to depict the finger of God touching and illuminating the stones presented by the brother of Jared (Fig. 4). The face of God is patterned on the Hopi symbol for “Tawa,” the Sun God who formed the world and its people. The brother of Jared wears a prayer feather on his head. His clothing is decorated with the Hopi whirlwind symbol, perhaps in reference to the “furious wind” that God caused to blow the Jaredite barges across the sea (Ether 6:5). The brother of Jared has climbed up several steps, and more steps arise between him and God. This may be in reference to the mountain where he called on the Lord in Ether 3, but the steps are also similar to the Hopi kiva symbol, which indicates the place where men first emerged from darkness underground and came up into light. Indeed, moving by faith from darkness into divine illumination is a central motif of this scripture passage, and the kiva symbol visualizes it in a way not typically seen in artwork of this scene.

The combination of these Hopi symbols with the brother of Jared story personalizes it for a particular group of people. But it also opens up the potential for new insights into the scripture for viewers everywhere. The Church History Museum owns this pottery and gave special permission for the catalog to include it. This piece is not publicly documented anywhere else and is one of hundreds like it that are only accessible to the public in the Book of Mormon Art Catalog.

An even more recent artist who has wrestled with these scriptures is Stephanie Kay Northrup, an American who chose to depict the brother of Jared in a more abstract style than is typical (Fig. 5). Northrup conflates several elements in the story to create one striking image. In the background, a small carving on the board along with drilled holes represents the Tower of Babel and the resulting confused languages. The brother of Jared is represented as a simplified form, the orange brushstrokes giving a sense of his determined movement forward and away from the tower. Inside his chest, a carved tower-like shape shows that it is through his personal faith and efforts that he will strive for heaven. Below him, sixteen orange rings reference the sixteen white stones he brought before the Lord. Rather than trying to create a realistic-looking scene, Northrup puts these abstract shapes in dialogue with each other, allowing the viewer to reflect on the full story of the brother of Jared in new ways.

Many other artists have engaged with the record of the brother of Jared in their art as well. The following four responses, written by the Brigham Young University undergraduate research assistants for the Book of Mormon Art Catalog, highlight additional lesser-known artistic representations of the brother of Jared.

As the only central repository for all Book of Mormon art, the catalog aims to not only recover the full history of imagery but also encourage new and varied representations. Along with the Maxwell Institute and Laura F. Willes Center, the Book of Mormon Art Catalog is currently hosting a BYU student art contest for original Book of Mormon art in 2023. Cash prizes and a feature in the Book of Mormon Art Catalog will be awarded in three categories: 1) attention to underrepresented figures and scenes, 2) use of unique stylistic and technical approaches, and 3) inclusion of a variety of cultures. With more than 600 artists already in the database, the catalog is an excellent platform for artists to reach a broader audience and promote their work.

Apart from its potential scholarly and pedagogical uses, the catalog can help people feel closer to the Book of Mormon and to Christ. On our website and social media channels, we post a weekly Come, Follow Me message with artwork from the catalog. We are also sharing short videos with artists and scholars to help viewers better understand the art. This year, in our scripture study series, it is inspiring to see through art the parallels between the witness of the New Testament and the witness of the Book of Mormon. Next year, in 2024, our series will provide even more contextualization of diverse artworks that could be used in the Come, Follow Me Book of Mormon curriculum. While the catalog makes exciting new scholarly analysis of LDS art possible, it is above all a tool for teachers, parents, and individuals to engage with the Book of Mormon. Art can help us read a scene or consider a message in ways we otherwise might not have, leading us to greater understanding. As you explore the artwork in the Book of Mormon Art Catalog, you will find things that surprise, challenge, edify, and delight you, and hopefully will inspire your own creations and revelations. That is the power of art.

Jennifer Champoux is an art historian and the Director of the Book of Mormon Art Catalog.

Jennifer wants to thank Laura Paulsen Howe, Art Curator at the Church History Museum, for helping her locate and research Book of Mormon art in their collection, and to Carrie Snow, Manager of Collections Care at the Church History Museum, who arranged for photography and image files of items.

A Catholic Reads the Book of Mormon: Folk Carvings of Roman Śledź

by Candace Brown

Too small to be called a real village, Malinówka is more of a settlement on the side of the road, difficult to find on even the most detailed map of Poland. Yet, it’s the home of the internationally acclaimed folk artist, Roman Śledź. At 20, Śledź came across a newspaper article on Polish folk carving and decided to try his hand at it. Within ten years, the self-taught artist developed a unique style and was displaying his work at individual exhibitions in Poland and Germany. In 2004, he was invited to the International Folk Art Market in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

In the early 1990s, Śledź was introduced to Walter Whipple, an American living in Warsaw while serving as a mission president for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Whipple had recently begun to collect Polish folk carvings, admiring their simple style and the sincere faith behind them. He and Śledź quickly formed a productive working relationship. After several years, Śledź surprised Whipple by proposing to create a new series of sculptures based on the Book of Mormon.

Some time before, Whipple had given Śledź a copy of the Book of Mormon but had not known that his friend read the book, cover to cover. While remaining deeply committed to his lifelong Catholic faith, Śledź was moved by the scripture’s stories of faith and eagerly seized the opportunity to depict them. He proposed several works and began to carve. With no additional exposure to Latter-day Saint art or theology, Śledź’s unique artistic interpretations—and his friendship with Whipple—demonstrate the power of story, art, and faith to foster connection among believing peoples from different religious backgrounds.

One Book of Mormon story which captured Śledź’s attention was that of the Jaredites coming to the promised land. In this double-sided sculpture, Śledź envisions two turning points in the account: first, the spiritual leader of the Jaredites, the brother of Jared, kneels in prayer upon finishing the Lord’s command to build eight boats that will carry his people across the sea (Fig. 6). He asks the Lord how his people will have light while in the ships. The Lord’s open arms reflect His open response: “What will ye that I should do . . . ?” (Ether 2:23). It is interesting to note that while Latter-day Saint artists typically imagine smooth, almond-shaped vessels, Śledź works within his visual framework and imagines multi-leveled barges similar to traditional depictions of Noah’s ark.

On the opposite side of the carving, Śledź shows what happens next: the brother of Jared constructs sixteen clear stones and takes them to the top of Mount Shelem (Fig. 7). There, he prays that the Lord will touch the stones and put heavenly light into them. Śledź imagines the miraculous moment when the Lord reaches out a finger to fulfill the request. Though Śledź is prone to solid jewel tones, each of the sixteen stones is topped with a dab of silver glitter to capture their special divine power. The title of the work is Palec Boży, or God’s Finger. Like the sculpture’s other side, the Lord’s body is similarly drenched in white paint to evoke Christ’s unembodied premortal status, with the exception of a single finger, which Śledź knew from the text that the brother of Jared had been able to see because of his great faith (Fig. 8).

What sets Śledź’s carving apart is that he does not stop with the great faith of the brother of Jared. At the base of the sculpture, two Jaredite families can be seen emerging from the forest (Fig. 9 and 10).

Their delicately carved faces betray some trepidation as well as curiosity as they peer around the edge of the carving to see the barges waiting to carry them across the water. While none look up to see the Lord hovering over them, they seem confident in taking the next step forward. None look back. Instead, they shoulder their bags and guide their lambs forward. The three lambs are covered in the same white paint as God, perhaps a nod to Christian iconography, implying that the lamb that will accompany the Jaredites is the Lamb of God. Perhaps Śledź had felt this same company in his own life, recognized it in the Book of Mormon, and finally envisioned it here.

Candace Brown received her BA in art history and curatorial studies from Brigham Young University where she was a research assistant for the Book of Mormon Art Catalog.

“Therefore I Show Myself Unto You”: Faith and Revelation in Annie Poon’s Brother of Jared Art

by Aliza Keller

Annie Poon’s art brings a playful and earnest light to the stories of the Book of Mormon. Each of her pieces strongly testify of the truth of the Book of Mormon and allow people of all ages and backgrounds to understand and find comfort in the stories there. She has over fifty pieces available to view in the catalog! The two pieces I’ll discuss in this essay tell the story of the brother of Jared.

The first piece, God’s Hand and Face (Fig. 11), shows Jesus Christ appearing to the brother of Jared as He touches the stones that have been carefully and faithfully prepared. Handwritten across the top of the image, Poon quotes Ether 3:13: “Therefore I show myself unto you…”, to contextualize the story. We see that the brother of Jared has prepared himself spiritually. He has gone up into the highest mountain, as described in Ether 3:1, and presented the stones to the Lord. In this image, the full body of Jesus Christ has appeared to the brother of Jared. This is one of only six artworks (of the 54 total images depicting this moment in the catalog) that shows the full form of the Savior rather than just His finger or a burst of light. This is likely because artists depicting this story tend to follow the same visual themes as the iconic Arnold Friberg, who depicted only a blinding light, rather than the actual form of Jesus Christ. Poon’s piece is in alignment with Friberg’s through its similar composition, but also builds upon it through the radical use of the image of the body of Christ.

Poon’s composition is also unusual in that Jesus Christ is kneeling on the same level as the brother of Jared. This implies an intimate and loving connection, rather than the impersonal appearance of deity that is sometimes portrayed in religious art. Christ is looking directly at him as He touches each stone one by one. Another aspect that shows the spiritual preparation the brother of Jared has taken is that his shoes are removed. This was a practice followed by many ancient prophets, as a sign of respect to God when receiving revelation. For example, when the Lord appeared to Moses through a burning bush in Exodus 3:5, He told him to remove his shoes, “for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground.” Poon’s allusion to other powerful scriptural stories of prophets emphasizes the faith of the brother of Jared as well as the sacrality of this event. The brother of Jared’s willingness to show his respect and love for the Lord, in connection with his great faith, are richly rewarded by this appearance of Jesus Christ.

An additional print by Poon, titled The Brother of Jared Dies (Fig. 12), depicts the burial site of the brother of Jared, his body surrounded by the glowing stones. The way that Poon immerses herself in the story is unique and beautiful. We don’t know what happened to these stones after the Jaredites crossed the ocean, in the same way that we don’t know if the brother of Jared removed his shoes as he prayed to the Lord. By depicting these things in this way, Poon is thinking deeply and truly engaging with the scriptures. She is inviting viewers to ponder questions about the scriptures that they may not have considered before and to wrestle with the text of the Book of Mormon.

I often think of the faith of the brother of Jared and compare it to my own. I sometimes wonder if there is any way to truly know in the same way that he did. A recent BYU devotional by Jeffrey S. McClellan offers a hopeful response to this idea:

If faith were a simple, clear knowledge, it would not be so inspiring. . . . Imperfect faith is still faith. By very definition, faith is incomplete, so if you feel you lack clarity and a sure knowledge, that is okay. That is faith. Be patient with the imperfection of your faith. The incompleteness gives faith its power.

Most of us will never have experiences of Godly visitation in our own lives. That does not make our faith and daily efforts to come closer to the Lord less meaningful or powerful than those of the brother of Jared. No matter what trials we are facing in our lives, the act of turning to God is an act of extreme faith.

As we pray for miracles—and expect them—we will find our faith strengthened daily. As we prepare ourselves spiritually for intimate and personal communions with God, just as Poon depicts in these images of the brother of Jared, we will be richly blessed with the Spirit of the Lord and will come to know of His will for us and our lives.

Aliza Keller is a senior in art education at Brigham Young University where she is a research assistant for the Book of Mormon Art Catalog.

“Against These Things”: Crossing the Great Deep with Rebecca Jensen

by Emma Belnap

“And behold, I prepare you against these things; for behold ye cannot cross this great deep save I prepare you against the waves of the sea, and the winds which have gone forth, and the floods which shall come.” (Ether 2:25)

In Rebecca Sorge Jensen’s striking painting Against These Things (Fig. 13), the viewer is given a sense of how helpless the Jaredites were on their journey to the promised land. The woman in the barge is facing immense odds. “The waves of the sea and the winds which have gone forth, and the floods which shall come” (Ether 2:25) are here exemplified through the exaggerated size of the fish and the barge. She has no hope to make it across the ocean without the guidance of the Lord. This helplessness is further exemplified by the woman’s body language; she lays in the fetal position, almost as if she were a child in the womb. Her eyes are closed and she appears to be praying, begging the Lord to help them with this seemingly impossible voyage.

This image also stands out because it tells a part of the Jaredite story not discussed in the scriptural account. Moroni glosses over the difficulty of their journey in his abridgement of their records. The crossing of the sea only receives nine verses in Ether 6, all of which highlight the Jaredites’ gratitude for the blessings of the Lord, rather than the hardships they experienced. Sometimes I see this reticence to discuss hardships in our modern-day church culture too. We may gloss over our difficult experiences so as not to seem pessimistic or ungrateful. But while gratitude for our blessings is important, so is talking about the hardships that make us truly grateful for those mercies.

I’ve learned through my own experience the gratitude we can experience in times of adversity. I was a missionary in upstate New York when COVID hit in March 2020. I will never forget the morning my companions and I woke to a text from our mission president telling us that we were in quarantine for the next two weeks. I was suddenly confined to my apartment, only allowed outside for an hour and a half every day. Instead of knocking on doors and street contacting, I spent my days calling phone number after phone number. Our isolation gradually extended to a month, then two, then indefinitely. With few people picking up the phone and even fewer showing kindness when they did, I began to feel like I was no longer fulfilling my purpose as a missionary. I started to plead with the Lord to let me go home but, after weeks of asking, it became apparent that the divine intervention I was so desperate for was not coming.

I imagine this is how the Jaredites also felt on their journey. Traveling in airtight barges with little light inside, submerged for hours and days at a time, and being completely unable to help themselves would be unimaginably challenging. I am sure the Jaredites woke every morning with a prayer that this would be the day they would reach land, only to be disappointed when the sun set and their deliverance had once again not come. Yet, they did not abandon hope. They continued to trust in the Lord and turn to Him, even and especially when His plan was not their plan. This is a painting about faith: faith that the Lord would carry them across the turbulent water to land, faith that He had a plan for them, the faith that, as they relied on Him, He would take them where He needed them to go and turn them into who He needed them to be.

As I gaze at the painting, I feel this Jaredite young woman’s story has become my own. I, like her, was secluded in a small space, not knowing if or when my deliverance would come. I felt battered by the metaphorical waves, winds, and floods of my journey. Even in this moment of desperation, though, the artist makes it clear that the Lord has not forsaken this young woman. Two of the glowing stones He touched rest at her head and feet, reminding her that she is not alone and that His light is with her in her silent struggles. Although the time I spent serving from my apartment on my mission was one of the hardest things I have experienced, I can look back now and know that I too was not forsaken. The Lord’s light was with me, even when I didn’t recognize it there.

Emma Belnap is a senior at Brigham Young University where she is studying art history and curatorial studies. She is a research assistant for the Book of Mormon Art Catalog.

Piece by Piece: Susana Silva’s 344 Series

by Elizabeth Finlayson

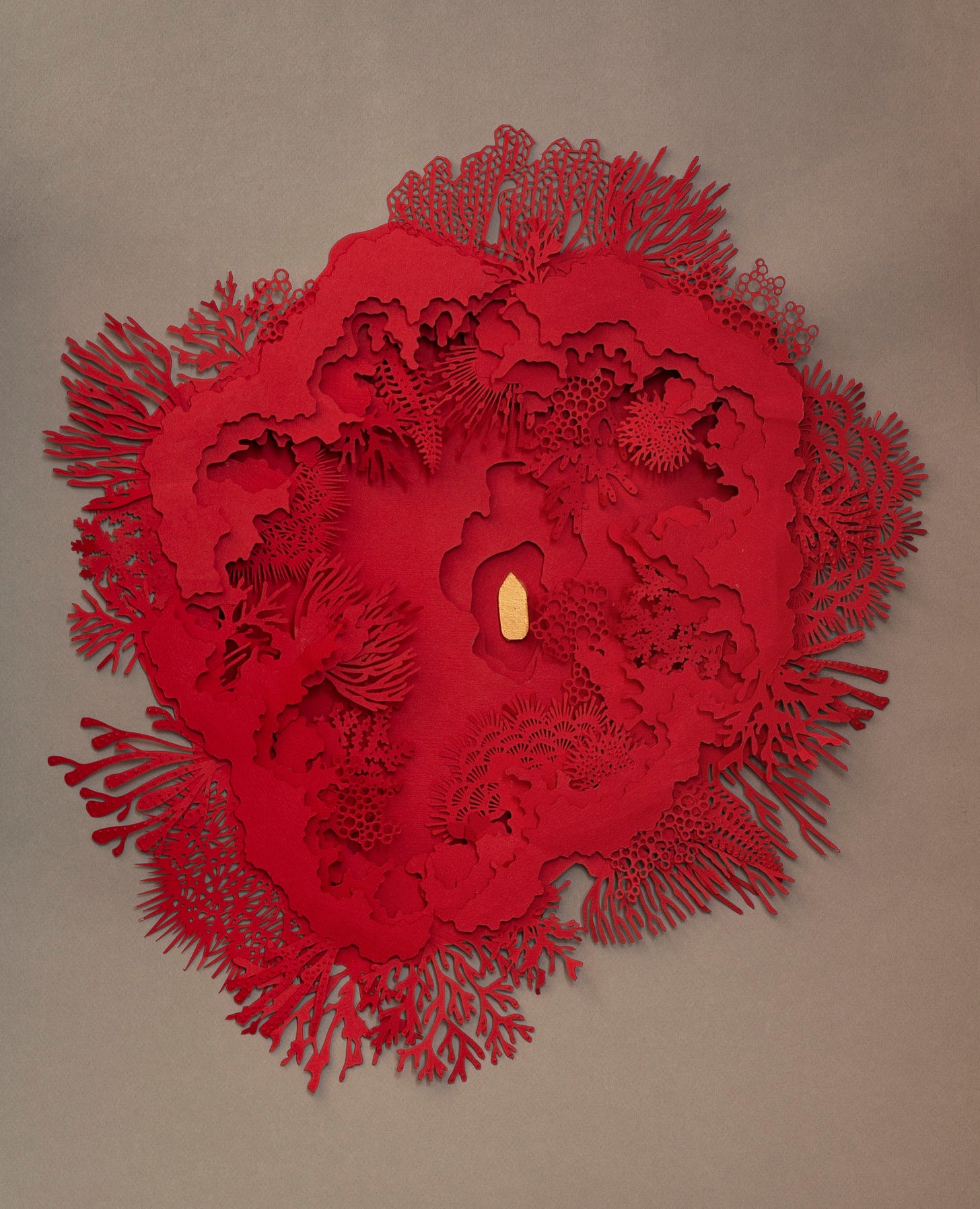

In an energetic scene of danger and risk, a series of tumultuous waves loom and crash over eight Jaredite barges in Susana Isabel Silva’s artwork 344 Días (344 Days) (Fig. 14). The vessels seem precariously small in comparison to the magnitude of the churning water, and yet they persist on their path towards the promised land. Radiating stones at the bottom of the composition highlight the faith required of each barge and symbolize hope in a dark and unknown period. Silva, an Argentinian papercut artist, relates her own experiences to those of the Jaredites, stating that, “I can also, like them, put my entire existence in the hand of God.”

344 Días is the first in a series of three artworks created by Silva called “344.” Each captures the life, vitality, and energy of large bodies of water, and emphasizes the miraculous journey that the Jaredites experienced. The second piece, In the Abyss (Fig. 15), is a bold visual of the Jaredite barges at their lowest, most isolated, and despairing moment of their voyage. Although small, the barge is not touched by the outstretched pieces of reef that threaten their safety. Rather, the boat resembles one of the shining stones touched by the Lord’s finger, radiating light, hope, and safety. Like the brother of Jared, we may also initially be frightened of the tasks that the Lord has asked us to accept, asking many questions about a seemingly impossible feat. In Ether 2 the brother of Jared asks many questions of the Lord and is given a solution for each one. The Lord said, “For behold, ye shall be as a whale in the midst of the sea; for the mountain waves shall dash upon you. Nevertheless, I will bring you up again out of the depths of the sea” (Ether 2:25-26). The final piece in Silva’s series, Emerging (Fig. 16), reveals the moment that the Lord’s promise to preserve them is fulfilled. The vessel has surfaced, the power of God is present, and the Jaredites’ belief has protected them.

As a research assistant for the Book of Mormon Art Catalog, I have spent countless hours searching through an ocean of information on museum websites, church magazines, artists’ galleries, and social media platforms looking for works to catalog and include on our website. Each of the research assistants has dedicated time to building a comprehensive collection of Book of Mormon artworks. The search was enlightening, fascinating, and continues to press forward. A wonderful aspect of having the website available to the public is that artists are now sending their artworks to us! Silva is one of these artists who reached out via our website and shared the inspiration behind her artworks. She desired “to put this powerful sequence of miraculous events on paper,” and explore the great expanse of the Jaredites’ faith in the Lord.

Patience, endurance, and innovation—three features that unite Silva’s paper cut artworks and the journey of the Jaredites. Silva’s process is meticulous and time consuming, as it requires her to delicately carve away small pieces of paper until the final product is eventually revealed. Beginning as only a blank sheet, each cut is an act of faith that something magnificent will come from the arduous technique. This attitude of approaching a task with an unknown future is what the Jaredites experienced as they crafted their barges. Constructed piece by piece, both the Jaredites’ vessels and Silva’s artworks are visual manifestations of trusting in the Lord’s guidance. Silva testified of her belief, saying, “I recognize my temporary struggles with my own monsters, those of my mind above all, that many times submerge me in anxiety or deep anguish. I can see in the distance the arm of the Lord, his tender mercy as I am strengthened and protected.”

Just as the Jaredites had to trust in the Lord and the light He offered them during their darkest days, we also must trust that He will raise us from the depths of our despair. I invite you to dive into the Book of Mormon Art Catalog and see what inspiration and hope can be offered to you through the visual testimonies of artists around the world.

Elizabeth Finlayson received her BA in art history and curatorial studies from Brigham Young University where she was a research assistant for the Book of Mormon Art Catalog.

This project is incredible! I was very touched by the artworks chosen by the students and their commentary.