Several months ago I attended a workshop about multiculturalism in which the speaker encouraged everyone to share stories. Open-hearted dialogue, she said, could help us understand one another and create connection instead of division.

However, the first person to share a story produced an entirely different result. Describing a disagreement she’d had with a professor, a woman near the front table claimed, “Israeli children are taught love, peace and acceptance, but Palestinian children are taught to hate.” It had been less than a month since war had erupted in Israel and Gaza, and a chill swept the room.

The woman’s words echoed in my mind for reasons besides the bewildering discomfort they produced in the room: I realized that I had heard nearly identical words before. In scripture. As the workshop leader awkwardly segued to another topic, I pulled out my smartphone and opened my Gospel Library app to search for those words: Taught. Children. Hate.

What I found that morning, and over the next several days, led me to think about a new way to apply Book of Mormon stories to our modern lives by examining the stories within the story — the narratives that Nephites and Lamanites told about each other, and how those stories shaped their world.

As the multiculturalism workshop continued, I went to Mosiah 10, where the Nephite leader Zeniff describes the Lamanites as “a wild, and ferocious, and a blood-thirsty people”1 who pass down stories about Nephi stealing the brass plates. “And thus they have taught their children that they should hate [the Nephites], and that they should murder them, and that they should rob and plunder them, and do all they could to destroy them.”2

For most of my life, reading the Book of Mormon dozens of times, I took this description at face value: the Lamanites hated Nephites. Obviously. But that morning I saw something deeper. This chapter of the Book of Mormon story is not a journalistic or historical description of the Lamanite education system. It’s part of a speech that a Nephite leader gives while preparing his troops to fight an approaching Lamanite army. He is trying to make it easier to fight back. And it works.

“Having told all these things unto my people concerning the Lamanites, I did stimulate them to go to battle with their might,” Zeniff reports. “We did drive them again out of our land; and we slew them with a great slaughter.”3

Was Zeniff lying about Lamanite beliefs? Not entirely. After all, a Lamanite army was marching toward his city at the time. Later in the Book of Mormon, the father of King Lamoni calls Nephite missionaries “sons of a liar [who] robbed our fathers,” and accuses them of planning to deceive his people, “that they again may rob us of our property.”4 It seems the Lamanites really did tell themselves the stories that Zeniff describes.

But the Nephites told stories too. Nephi’s record reads like an origin story of two nations, complete with details of the many times that Laman and Lemuel had wronged him. Not even one generation after the Nephites split from the Lamanites, Jacob chastises his brethren for hating the Lamanites “because of their filthiness and the cursing which hath come upon their skins.”5 The books of Enos and Jarom describe the Lamanites in various states of bloodthirstiness and depravity.6

As I began to examine these narratives side by side—the Lamanites calling the Nephites robbers, and the Nephites describing the Lamanites as bloodthirsty savages who teach their children to hate—I couldn’t help but think more deeply about the consequences of such stories. They ultimately fueled centuries of conflict that cost countless lives.

Both the Lamanites and the Nephites engaged in what social psychologist Jonathan Haidt calls “common enemy identity politics.” Haidt argues that, “Identifying a common enemy is an effective way to enlarge and motivate your tribe,” but he also links these narratives to polarization and poor mental health. He contrasts this with using “common humanity identity politics,” practiced by leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., to unite people.

The stories we tell, whether they emphasize a common enemy or common humanity, shape us. In the case of the Nephites, the stories take a toll. When Ammon and his fellow missionaries decide to preach to the Lamanites, hoping to cure the hatred between the groups, some Nephites mock them. They essentially ask, “Do you think you can actually convince those stiffnecked, bloodthirsty, sinful Lamanites to believe as we do?”7

And here’s the kicker: “And moreover they did say: Let us take up arms against them, that we destroy them and their iniquity out of the land.”8 After generations of rehearsing stories about Lamanite hatred, many Nephites are ready to commit genocide.

We know the rest of the story though. Thousands of these “bloodthirsty” Lamanites bury their weapons of war and many gave their lives to uphold a vow of peace.9 The Nephite stories had been incomplete for generations.

I’m impressed how Christ’s ministry changes the stories that Nephites and Lamanites tell about each other. In fact, he erases the distinction between them. In 3 Nephi, we go nearly twenty chapters with no mention of the word “Nephite,” and with only positive references to the word “Lamanite.”10 The Savior saw Lehi’s descendents as a unified body, rather than defining them by their differences. As soon as Christ was among them, “there was not any manner of -ites.”11

During that workshop about multiculturalism, the comment about children being taught to hate sent me on a journey of understanding the stories Nephites and Lamanites told about each other. I see echoes in many of the stories that divide our world today. Both Israelis and Palestinians have accused their opponents of teaching children to hate, sharing online videos from classrooms to support their point. In the United States, political partisans believe their opponents are more immoral and closed-minded, less intelligent and less honest. There is no shortage of stories to divide us.

In his recent general conference address, “Peacemakers Needed,” President Russell M. Nelson recalled one of the best known stories of the Book of Mormon, declaring, “Now is the time to bury your weapons of war.” Seeing how Nephites and Lamanites used stories to stoke war makes me think that stories may be among the most potent weapons that we need to lay down—even bury deep beneath the soil of repentance and brotherly love.

After Israeli troops exited Gaza recently, a New York Times headline reminded us that the “war is not over.” That statement is all too true. I don’t have an easy answer to ongoing wars or political conflicts. But the Book of Mormon shows where the answer begins. Enduring peace begins not with winning a war or an election. Neither does peace start when we separate ourselves from those with whom we disagree. Peace begins when we see beyond the stories we tell about ourselves and others and see each other as children of God.

Bryan Gentry writes nonfiction on topics including personal development, psychology, open-minded discourse, and faith, as well as fiction and poetry. A graduate of Southern Virginia University, he lives in Columbia, S.C., with his wife and children.

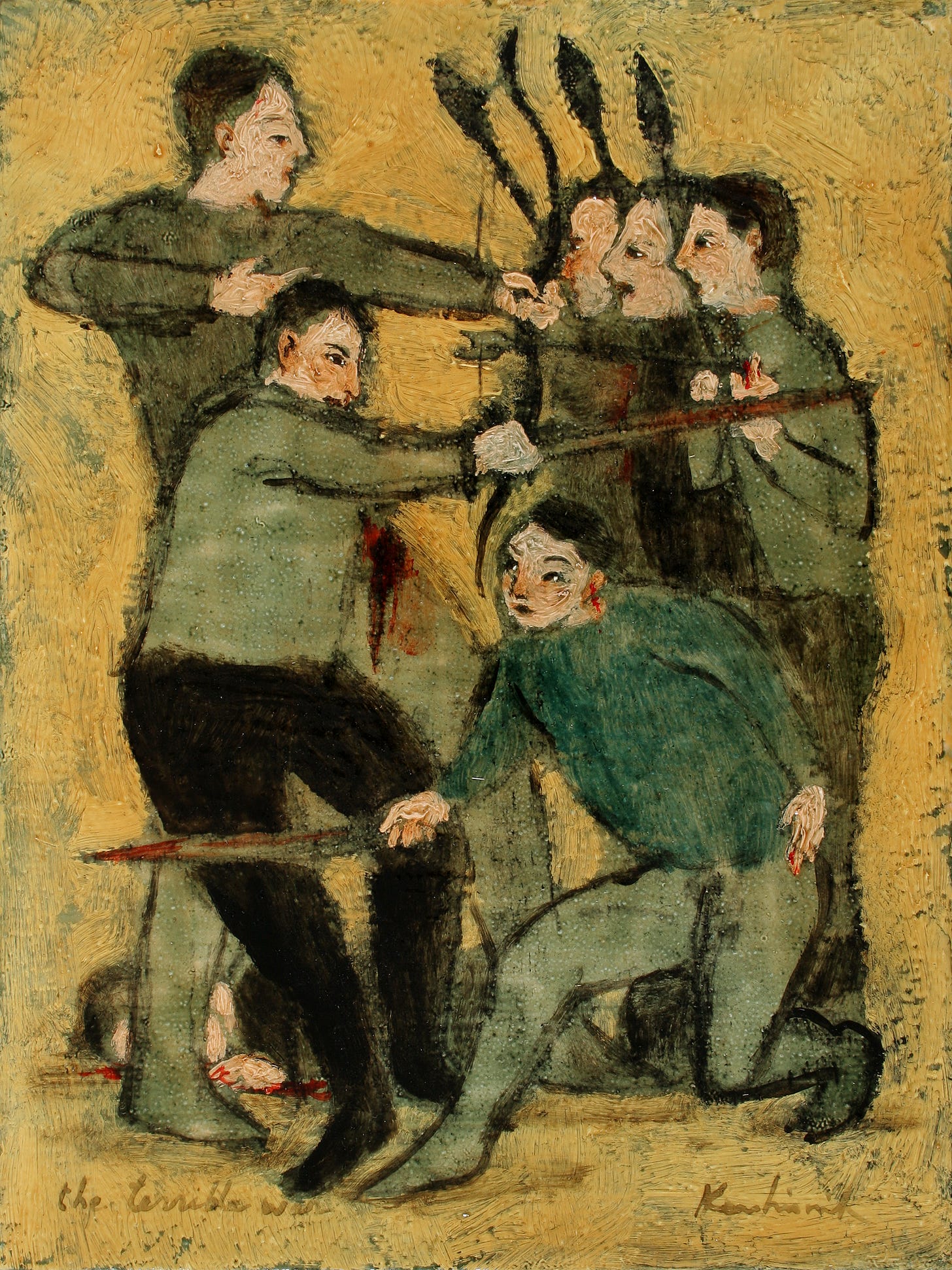

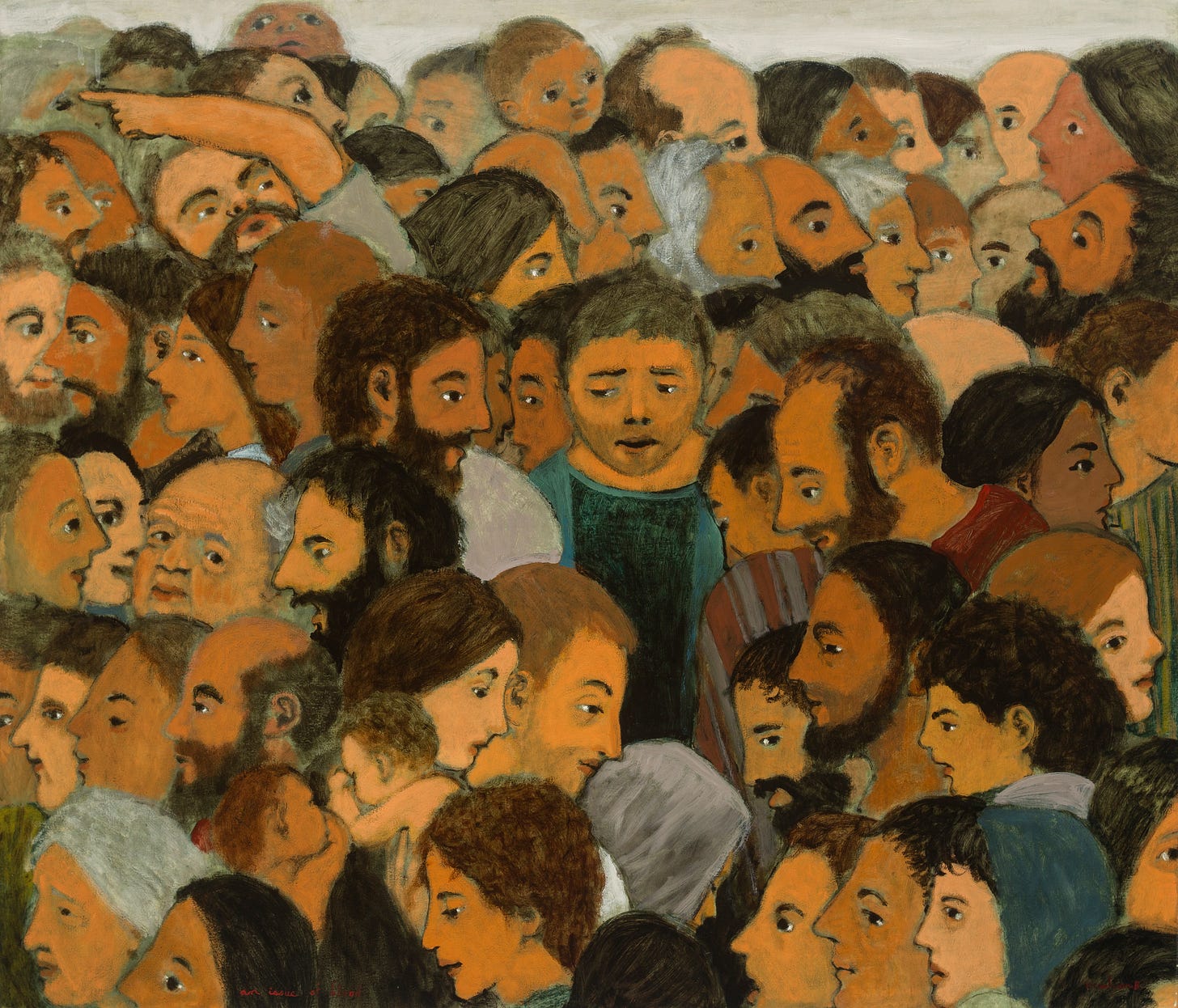

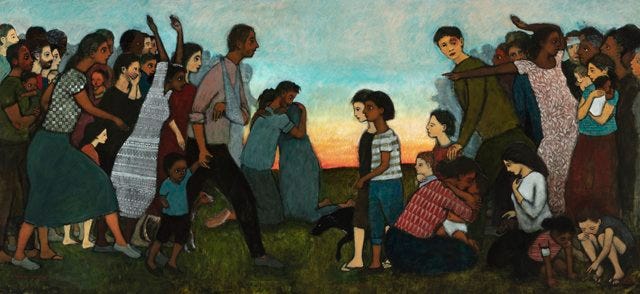

Art by Brian Kershisnik.

Zeniff and “The Ruler”

Closing his eyes and wincing slightly in an expression of earnest yearning, my Sociology professor confessed: “I want to feel what a Buddhist feels when she is prostrating herself in front of the Buddha. She has something I don’t, and I want that connection. I want to be her in that moment.”

Issue 4 Call for Submissions

We are starting work on Wayfare Issue 4 and invite you to send us your pitches and ideas for essays. You can learn more about what we're looking for in our pitch guide. Get in touch at wayfare@faithmatters.org. And if you're an artist or poet, we'd love to hear from you too!

Mosiah 10:12

Mosiah 10:17

Mosiah 10: 19-20

Alma 10:13

Jacob 3:5

Enos 1:20, Jarom 1:16

Alma 26:24

Alma 26:25

Alma 24:19

3 Nephi 9:20, 10:18, 23:9

4 Nephi 1:17

I am pondering on this theme, too. In the margins of 2 Nephi 5 I have copied out these words from President Uchtdorf’s 2013 “What is Truth” speech.

“In the Book of Mormon, both the Nephites as well as the Lamanites created their own “truths” about each other. The Nephites’ “truth” about the Lamanites was that they “were a wild, and ferocious, and a blood-thirsty people,” never able to accept the gospel. The Lamanites’ “truth” about the Nephites was that Nephi had stolen his brother’s birthright and that Nephi’s descendants were liars who continued to rob the Lamanites of what was rightfully theirs. These “truths” fed their hatred for one another until it finally consumed them all.”

My margins are wide and I wrote small 😅. I think this profound lesson is right there plain in the text, but my common and casual approach to reading kept me from slowing down enough to sit with the implications (particularly of Nephite self-righteousness). I now feel it urgently and can’t stop seeing this theme everywhere in the text and my life.

Enjoyed this. I am in Jerusalem working this week for the Foundation for Religious Diplomacy. You would like what we are doing. Our new website is going live in a couple of weeks. Thanks