Some live all their lives without discovering this truth; that the noblest and most terrible power we possess is the power we have, each of us, over the chance-met, the stranger, the passer-by outside your life and your kin. – Dorothy Dunnett1

Aimless for my first semester in college, I still lacked clarity even after two years of mission service. One day I happened upon a description of a major I had never heard of. I went straight to the related department and conversed with the chair. After several minutes, during which I felt a happiness akin to conversion, I rose to leave. As he ushered me out the door, he put his hand on my shoulder, and welcomed me onto a new path. The firm touch was like a seal on the implicit agreement. The conversation had been pivotal, but the human touch added something beautiful and made the encounter a personal rather than intellectual transition. I felt embraced by a mentor as well as persuaded by an appealing future.

Some years later, I was a young, relatively untested academic. Not at all comfortable delivering papers, I had managed to do so at a speaker series organized by Gene England. I dreaded the Q&A, but it was part of the package deal and I faced a sea of hands. The audience was not entirely receptive to my remarks, and one question—probably less hostile than I interpreted it to be—threw me completely. In the midst of that hell where a pause threatens to stretch into paralysis, I suddenly felt from behind me a gentle hand on my shoulder. “I believe,” England interposed, “that Terryl answers that question in his chapter . . .” Then he slipped back to his seat, leaving me to segue more comfortably into a full response. The touch had been more than collateral movement: it spoke of friendly support and rescue and even—in an academic conference—charity.

In another time and place, I was abroad with some family members. Negotiating traffic on autobahns and managing a fractious child had exhausted my reserves of patience and good will. Driven to exasperation by a final irritant, I gave up in the face of a burgeoning eruption. Microseconds into the verbal violence a hand patted my shoulder. I turned to see a younger son, smiling good naturedly and saying, “it’s going to be ok, Dad. Don’t worry about it.” The words would have rolled off as so much futile cliché, but something about the touch changed their effect. My son had physically broached the envelope of my anger, and in so doing, had made it no more durable than a soap bubble.

My father died after a painful but courageously uncomplaining battle with cancer. Most father-son relationships are complicated—and mine was too, marked by years of conflict and distance and anger. By the end, our relationship had evolved into genuine love and friendship. I had not been present at his actual passing, though I was there on occasions when we thought it was imminent. In the months following, he was now and again present in dreams—I suppose as I was coming to terms with one of the most profound losses that most of us are required to work through in life. The last time that happened, I did not see him—but I felt the loving pressure of a hand on my shoulder.

When I first encountered the words of Dorothy Dunnett about the “noblest and most terrible power” we possess, I knew from experience they were no understatement. Those four moments of a hand on my shoulder bore evidence to me of the ponderous effect that human touch can have out of all proportion to its physical weightiness. Numerous times in my life, that touch has been verbal, communicated in person, by a kind note, or a thoughtful communication. It has also been true for me, as it doubtless is for every living person, that the right word or encouragement or consolation would have made a significant difference in a day or other possible futures.

We know that out of “small things” can arise great consequences. Remembering how little those four gestures cost the agents behind them, and how enduring their effects in my life, causes me to marvel at the wonderful lack of economy in the eternal order of things. It betokens an invitation I hope to relish more frequently.

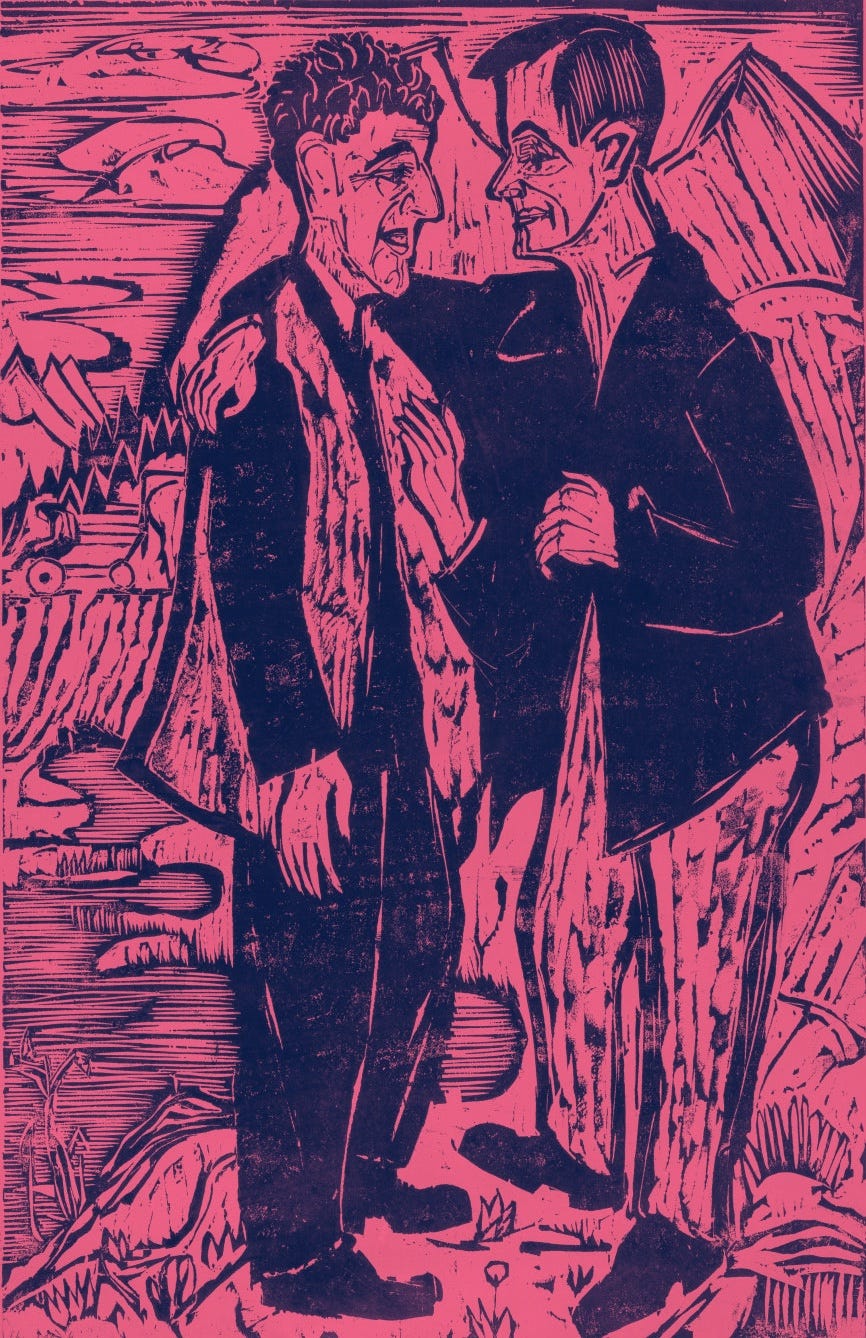

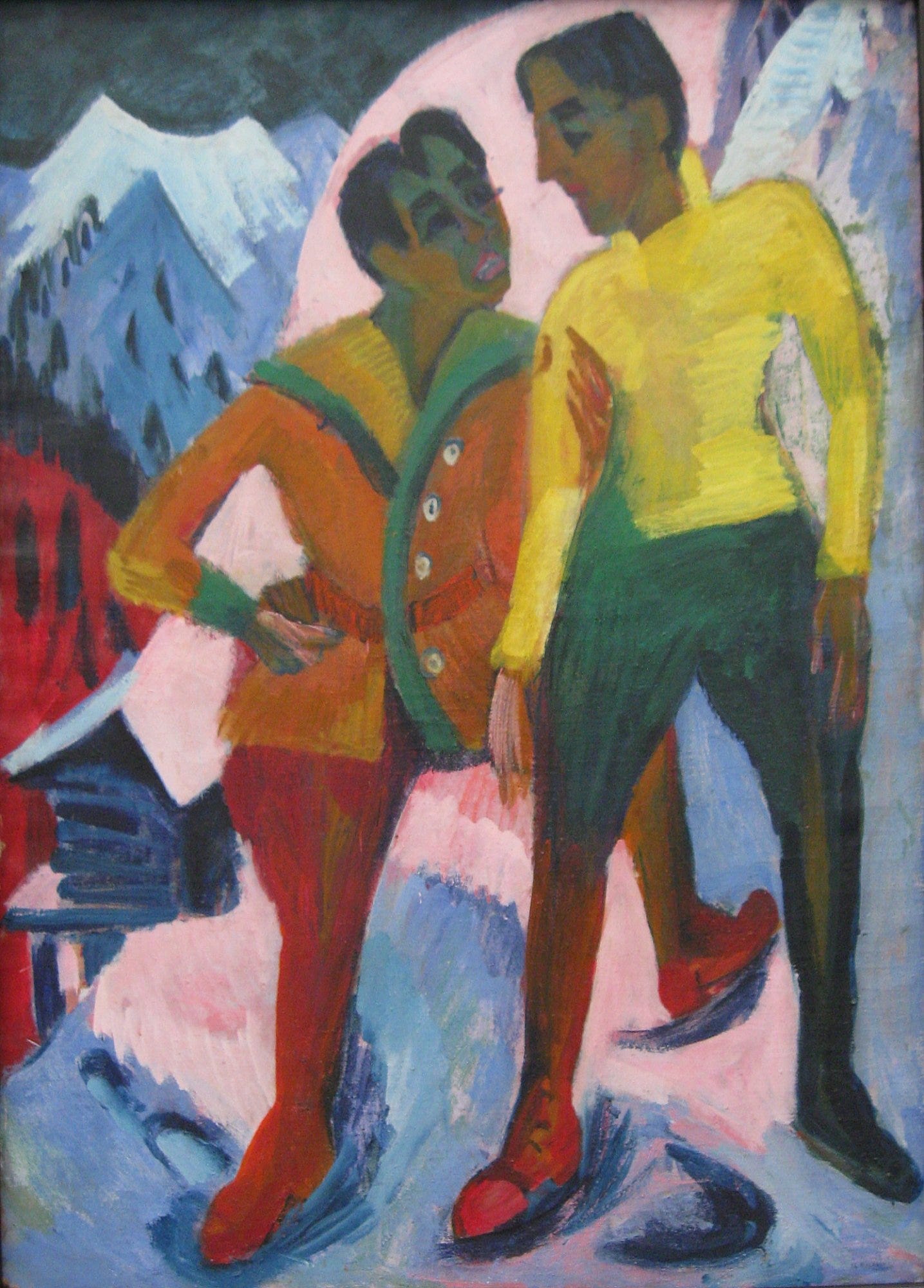

Artwork by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, first subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."

Dorothy Dunnett, Queen’s Play, The Lymond Chronicles (New York: Vintage Books, 1997).

I so appreciate your acknowledgment of the importance that a simple touch can so profoundly add to moments of support and connection.

Our Puritanical culture often encourages less physical affection and a withholding of that connection. A reminder of its importance is crucial to creating unity and communion. Thank you.

Such beautiful gestures of love. Thanks for sharing Terryl ❤️