Toward the end of the play Our Town, Emily, in tears after having been given a chance to relive some moments of a regular day in her life, turns to the Stage Manager and asks, “Does anyone ever realize life while they live—every, every minute?” The Stage Manager’s first answer is no, but then he reconsiders: “Saints and poets maybe . . . they do some.”

What do you think? Do poets actually live differently from other people? If so, how?

Poets are sometimes described as seers. I think that when people call poets seers, they are doing so because of some experience they’ve had with poetry as readers that makes them suspect that poets, in order to create the words that affect the readers so deeply, must be seeing (and maybe living) differently than other people do.

As for the line in Our Town, I’m not sure which comes first for Wilder. Is he asserting that engagement in the work of writing poetry leads to intense, attentive living, or that “poet” is a good title for someone who has managed to live this way? Technically, the definition of poet is simply “a person who writes poetry.” Of course, anyone can and probably should write poetry. But few would argue that Dr. Seuss’s poetry and Edgar A. Guest’s poetry and the “Footprints in the Sand” poem and Mary Oliver’s poetry and that of Wallace Stevens and Rae Armantrout all arise from the same kind of person, or from the same kind of attention.

I think that when Wilder postulates that poets—or any artists—might experience life more intently, he is referring only to those poets (and painters, and potters, and musicians) who have managed to create something that enables readers to feel their own experience more deeply. Perhaps also he is speaking from his own experience of creating art because he knows that in order for him to create art that moves others, he must engage in a certain kind of attentiveness.

What, then, is that attentiveness, and when in a writer’s process does it take place? Is it in the living, or in the work—or both?

There is a sort of cultural awe, sometimes, about this mysterious, god-struck poet-figure who sees more clearly and is more inspired than regular mortals (inspiration: being breathed into by God). That divine lightning strike is what calls the poet, and it is then her job to put her visions into words for the rest of us. Denise Levertov speaks of the poet as priest and the poem as a temple enabling communion for “those who need but can’t make their own poems.”1 A poet sees, and then fulfils her duty to relay. But I think that many poets would probably say that it is the work that produces the seeing in the poet as well as, later, in the reader. That is, the work that poets engage in because of a commitment to create requires—and therefore produces—greater attentiveness. So, yes, a poet may be “realizing life” more intensely, but this realization comes because of, and through, the work. For those who see this attentiveness as spiritual, the craft of poetry becomes a spiritual practice. In his book on poetry, The Art of Paying Attention, poet Donald Revell says that “attention is a piety and . . . the unaggressive articulation of attention in poems may be a form of prayer, an instance of worship, a forwarding of peace.”

The role of attentiveness plays a part in my own work in four ways:

I must be attentive to the world in order to find a subject for a poem and a way into the piece.

I must be attentive to the work in order to craft the poem.

I want my poem to demand attentiveness from my reader, and reward it.

I want my poem to make my reader more attentive to the subject of the poem specifically, and the world generally.

Each of these aspects of attentiveness can inform, mirror, or at least stand as a metaphor for spiritual practice.

1. I must be attentive to the world in order to find subjects and approaches for my work.

For one thing, because of my commitment to produce poetry, I have developed practices that have increased my ability to welcome and recognize triggering subjects (the subjects of future poems). For example, I make it a habit to write down ideas as soon as I get them, even if they come at 2:00 a.m. When you greet an idea with courtesy, welcoming it as an honored guest, more ideas come.

President Henry B. Eyring makes a similar claim about the spiritual practice of seeing the hand of God in our lives: If we write these things down, we will recognize more of them in our lives.

Another practice that increases my ability to recognize poetic subjects is a rigorous commitment to regular work that is independent of a feeling of inspiration. I give myself assignments: “I must produce a poem today,” and show up to work whether I feel inspired or not.

The assignment doesn’t make me more inspired throughout the day. In fact, I’ve found it a little unhealthy to maintain a constant purposeful watchfulness for subjects just because I know I’ll be writing a poem later. Like a monetized personal blogger knowing she must report on her day, the temptation is to watch myself living in a sort of self-consciousness that becomes a cheap substitute to the real attentiveness of full participation in the moment. Rather, I prefer my work to arise from attentive and unselfconscious living followed by later attentiveness in recollection at my desk. This is similar to Wordsworth’s concept of “emotion recollected in tranquility,” but I would assert that the recollection itself can bring up greater emotion than what I originally experienced because of my thoughtful attention to the situation in retrospect. Though the original situation may have brought up very little emotion, the act of committing to produce work creates the space for a lived moment to affect. My task at the desk, then, is to attend carefully to the subject. What is it really like? How does it look, or taste? What are metaphors for it, or what is it a metaphor for? What does it remind me of?

I believe this attending is a spiritual practice. By doing it, I am homing in on truth. I am maximizing experience. I am, because of my attentiveness to the experience in retrospect, having “life more abundantly” (John 10:10). Here, in retrospect, is where I feel most as if I am poetically “seeing.”

This aspect of creation deeply resembles my faith practice. My personal definition of faith is action because of a commitment—a decision, backed by action, to move forward, where the decision does not depend on anything from outside (such as whether I’m “feeling it” on a particular day or whether an angel has, or has not, visited me). When I write, I show faith by committing to an assignment even if I don’t feel inspired, moving my fingers on a keyboard hoping to catch the lightning if it comes. In my religious life, I have committed to faithful activity. Faith doesn’t require an emotion, nor does it depend on something I might receive from outside myself; it is simply a decision to move my feet. If and when God decides to appear to me—and He has, and He does—He finds me already in motion, attending.

2. I must be attentive to my work.

Once I’ve found my topic and my approach (which usually doesn’t happen until I’ve got lots of language already), I begin the work of forming language into a poem. Like pretty much anyone who works, I long for a sense of flow—a loss of self, a feeling of timelessness—but a lot of time, I am just trudging forward, doing the things I know how to do. This involves examining each line for possibilities, always pushing towards freshness, which could come in the form of a surprising image or metaphor, for example, or some play with sound.

I attend and attend, assessing, trying things out. I make lists of metaphors. I play with alternate phrasings for rhythm and sound. I collapse the lines into a paragraph and break them up again. In all of this work, I am striving to maximize the experience for the reader.

. . . which brings me to #3:

3. I want my poem to demand attentiveness from the reader.

People continue to debate the difference between poetry and prose, but one thing I think everyone can agree on is that when you simply want to communicate information to someone (what time the meeting will be held, for example, or why your brand of air conditioner is more cost-effective than another), you use prose. Poetry is for something else.

Poetry requires more interaction than prose. Through metaphor, symbolism, creative line breaks, musicality, etc., a poem invites the reader to participate in the experience. For example, consider this line from e. e. cummings:

“nobody not even the rain has such small hands”

When we encounter a line like this, our mind sparks. What? Rain doesn’t have hands. But I guess if it did, the hands would be very small. And yes, now that I think of it (sensory memory), rain can sometimes feel like very soft hands patting my skin tenderly . . .

Poems differ in the amount of participation they ask of a reader. Because I most enjoy poetry that is immediately accessible (that is, not highly demanding at first) but also rewarding when I attend more carefully through a second read, that’s the kind of poetry experience I strive to create. As I work at my craft, I attend to the way the words invite the reader’s attention, both on first entering the poem and then later with a re-read.

Perhaps we could say that the best poetry respects the reader’s free agency, because it has space in which the reader can enter the poem more deeply if she desires. Instead of pounding a message hard and directly as prose would, poetry values the reader’s active engagement so much that it risks misinterpretation rather than closing all gaps.

Similarly, I believe that God has deliberately allowed poetic gaps within the scriptures because he expects us to interact with the words. Jesus taught in parables, risking misinterpretation—perhaps even inviting multiple interpretations—saying that those with ears to hear would hear. Attending to and interacting with scriptural text is a spiritual practice.

4. Finally, I hope my poem will make the reader more attentive to the world.

I feel my poem is successful if a reader enjoys the experience it creates. But much better is if, after reading it, my reader turns to the world and sees it differently because of the experience. Maybe my poem about—say—living with a teenager could help a parent of a teenager see his or her own life differently. Moses cried out,“Would God that all the Lord’s people were prophets” (Numbers 11:29). My institute teacher used to say that a prophet’s role is to create more prophets. Perhaps a poet’s role is to create more poets. Ideally, a poet escorts the reader to the mountain from which, after the holy experience, the reader returns to his life carrying not just his new way of seeing the subject of the poem, but also a new way of seeing in general. Perhaps a really good poem delivers its reader his or her own Urim and Thummim. In this way, poetry can play a role in the reader’s spiritual practice by increasing his attentiveness to his own experience.

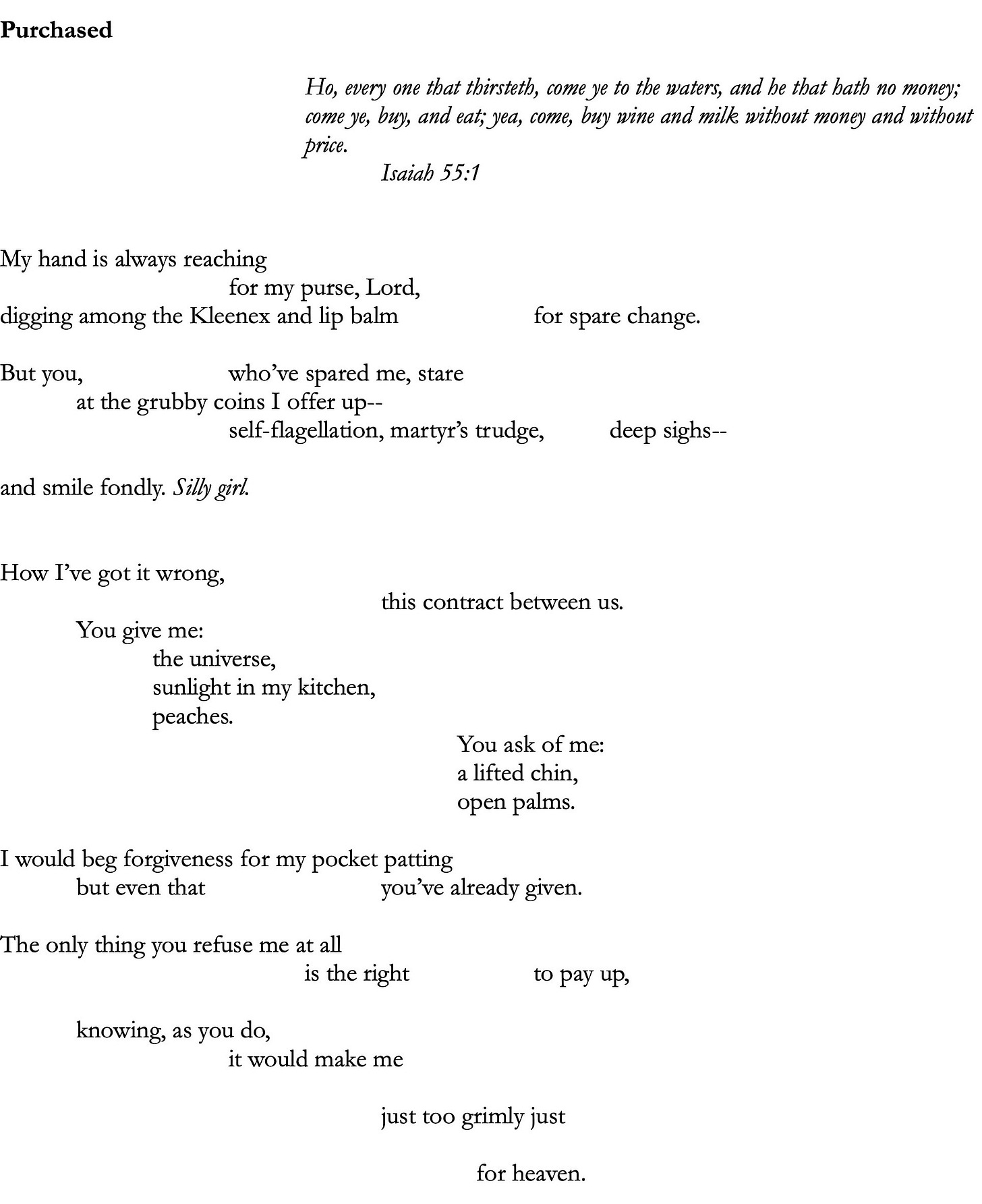

Let me conclude by using a specific poem to provide an example of the four ways attentiveness comes to play in the experience of poetry. Here is my poem, “Purchased.”

First, I found the subject of the poem by being attentive to my own experience. I had assigned myself to write a poem. I looked through notes I had taken on my phone of potential poetry topics as they had occurred to me over past days. One note had been written on a day I had spoken in irritation to my kids. Frustrated that I still hadn’t conquered this tendency after years of trying, I had suddenly realized that I might never permanently fix this weakness in myself. Did that mean, then, that I wasn’t on the right path to God? What, then, did the Atonement actually mean? Now, as I sat at my desk, fingers moving, worrying the subject and pushing on it, I attended to the topic of human weakness and God’s grace. I imagined what God would say to me about it, and began to find language that might make a poem. You see how this work resembles prayer in a way. The work of finding words was also a conversation with God.

I knew I had found an entrance into the poem and a mode that I wanted to use when I felt that what I had collected to say might be of interest to someone else, that it might spark a new way of looking at daily repentance for my reader. Then I generated a lot of language, trying out different voices (God’s to me, mine to God). Finally, I began attending to the actual shape of the language on the page. I drafted in my usual longish lines, then looked for places that made interesting line breaks. I read aloud, attending to what the reader might experience while reading the poem.

I decided to try some unique spacing on the page, something I rarely do because such forms can seem overly-manipulative to me as a reader. I decided to risk that, though, because I wanted to mimic the feeling of prayer—the halting progress, the pausing for response, the searching for greater self honesty—and I used uneven, disruptive spacing to create that feeling.

I examined each line. Was I using enough imagery? Could other images be better? I looked at the sounds in each line. Would more attention to musicality add to or detract from the particular tone I wanted (here, familiar but also tenderly holy)? I examined every word. I added an epigraph to give the reader more context so that she can more quickly access the subject and context.

I felt I was done when the words, line breaks, etc. functioned together, as well as I could tell, to create an experience for the reader that would enable her to re-see the process of accepting and relying on the Savior’s atonement.

Now that you’ve joined me in this poem-temple that I created, what do you think? Did it work? I hope that attending to my poem makes you attend a little more to what the Atonement means to you. I hope that in this way I am helping you more attentively “realize life,” as Wilder claims, becoming a little more of a seer yourself.

Darlene Young has published numerous essays as well as three poetry collections (most recently, Count Me In, Signature 2024). A recipient of the Smith-Pettit Foundation Award for Outstanding Contribution to Mormon Letters, she teaches writing at Brigham Young University. Her work has been noted in Best American Essays and nominated for Pushcart Prizes. She lives in South Jordan, Utah. Find more about her at darlene-young.com.

Art from Rain Series by Shelly Coleman.

Levertov, Denise, “Origins of a Poem,” in Claims for Poetry, ed. Donald Hall (U of MIchigan Press, 1982), 257.

Brilliant.

Wonderful. You are a maker of poets. Thank you, Darlene.