Rotate the Crops: A Metaphor for the Art of Living

Part One

Faith is about living truths that bear good fruit, and truth grows better in community experiment than brittle propositions. This essay outlines the crop rotation analogy: what it offers, its limitations, and why we should usually prefer it to the shelf and the bundle analogies for truth claims. The cultivation and harvest of fruitful truth takes seed in the agricultural metaphor of crop rotation.

I spent a couple youthful summers walking up and down the rows in mile-long cornfields outside of my hometown in Iowa. This coming of age ritual for many Iowan teenagers goes by the name detasseling. Climb into the back of pickup trucks in a local parking lot at twilight. Trundle out to the cornfields by early morning. Remove by gloved hand the pollen tassel from the corn—plant by plant, row after row—for fields and days on end. The sun grows hot, even in the early morning. By mid morning the sweat swims into the cuts left by sharp husk edges. As I glance up on those fields, my thoughts bend toward the eternities: I remember now how hard it was to tell the difference between such thoughts and making it to the end of the field.

Somewhere on those endless cloudless fields was planted a seed, a germ of an idea. Be practical, do what works. Since then I have seen many dear friends in my career and church communities, despite priding themselves as relatively practical people, thinking about timeless questions of faith and truth with a certain fragility. Some ways of thinking have consequences for the art of living, or at least so I contend here: the resulting essay stretches as long as a row of corn in the endless Iowan plains, split into three parts for convenience. The abstract style is—not without a touch of irony—an experimental antidote to what I perceive to be a particular poverty in public discussion about truth and faith. Too often do we discuss truth and faith in personal terms, absolute terms, or not at all. None of these will do. How about an essay whose length and style aims to slow the reading process instead? It is meant to take a long time. This essay uses an abstract plain style—a philosophical evasion of philosophy, to borrow from Cornel West—to advance an extended agricultural analogy that makes this point: a life of love, learning, and truth cultivation grounds itself in collective experience, evidence, and inference. In seeking better ways to think, talk, and live faith and truths publicly, this essay explores an analogy at once radical, practical, and limited: it calls on its reader to live faithfully in raising truth that works better together.

Fellow reader, join me on a long walk down one row of corn together. In it, I follow an Old Testament farming analogy.

Rotate the crops.

Leviticus 25 teaches the Hebrew concept of shmita (שמיטה, literally “release”)—the idea that we should rotate our crops across fields every seven years. A sabbatical year lets the fields lie fallow. Jubilee years wash away debt every seven times seven years, a practice almost absent in contemporary corporate capitalism. Then, in the eighth year, we rotate the crops, plant new permutations of our desired crops, and start anew. Old crops, new soil, as it were. Exodus 23:10–11 continues the theme: “Plant and harvest your crops for six years, but let the land rest and lie fallow during the seventh year. Then let the poor among you harvest any volunteer crop that may come up. Leave the rest for the animals [wildlife] to eat.”

Let's first take this literally: periodically moving each type of plant from field to field enriches the soil and the harvest, since farmers (especially industrial monocropping farmers) who do not rotate crops burn out the soil after repeated plantings of the same crop. The reasoning here has to do with the biome chemistry of the soil: by rotating crops, plants balance one another out, maintaining the soil as a medium of growth. For example, corn takes nitrogen out of the soil, and beans deposit nitrogen back. Little about the thorns and thistles of modern-day industrial farming is old-fashioned: agriculture ties in curiously to modern technology and media. Rural and urban areas are not opposites.

The agricultural and biochemical advantages of rotating the crops are clear enough, but, echoing Patrick Mason's language elsewhere, what might these instructions for planting teach us about living a life of faith and truth? How could shmita work as a metaphor for the art of living? Rotating the crops of my faith teaches me to seek short- to mid-term prudent resource management, invites charitable giving, and inspires a psychology of short-term gathering, then letting go of profit. Don’t work the land; tend it. Crop rotation dovetails with the equilibrium-restoring practices of doing work six days a week, rotating through a multi-year curriculum, giving a portion of one's increase to charity, and foregoing meals periodically to donate the proceeds to benefit people in need.

What else could crop rotation teach about the art of living, knowing, and doing?

Crop Rotation as an Analogy for Truth Cultivation.

The rough analogy follows: faithful living is like farming and gardening insofar as truth claims are like plants; truth is like the fruit of those plants.

Faithful living : sustainable agriculture :: truth claims : living plants :: truth : fruit.

(I mean “fruit” in the broadest sense, including all organic produce, especially vegetables.) The analogy broadens out a bit next: developing healthy, nourishing crops in life requires the rhythms of cultivation, care, rotation, storage, and giving away, and the same holds true for our beliefs. To live as a crop rotator means to develop an inquiring patience, an experimental attitude, a community orientation, a talent for learning when to let go and listen, and a firm belief in the critical goodness of truth cultivation. As Soren Kierkegaard, that dour Dane extraordinaire, pointed out in the only other public-facing essay on crop rotation I know, to rotate one’s crops means to see things anew, not merely to dodge boredom but as a higher faithfulness to an artfully creative life. The fourth-century Neoplatonist Antoninus writes, “You can begin a new life. Only see things afresh as you used to see them. In this consists the new life."

In this analogy, crop-like beliefs do not appear as mossy stones or static true-or-false propositions: beliefs appear as living plants whose roots dig in, either flowering into fruit (and vegetables) or withering on the vine or in the sand. They grow, molt, and bear produce—or not so much. We can observe whether or not our truth claims grow.

Some modern truth language comes from a misplaced tradition of what we might call “glancing up.” Farseeing visionaries and wayfinders have for centuries looked skyward to the heavens and returned with beautiful mysteries of the beyond. There is nothing wrong (and indeed a lot that is right) with looking up in awe at truth unless doing so makes truth feel fragile, distanced, or unworkable. With that in mind, I argue that crop rotation offers a better analogy than scanning the horizons in search of truth and then, once we have it, storing truth on the shelf and by the bundle. In the shelf analogy, people have cognitive shelves onto which they set unanswered or upsetting truth claims. The bundle analogy ties together truth claims into a series of often logically interdependent if-then statements: if A is true, then B is true; if B is true, then C is true, etc. Both of these analogies teeter atop steep cognitive cliffs. Cliffs make familiar vistas for mountain-rich faith traditions to skygaze and glance up, but note the risk too: one overturned rock can also cause an avalanche of causation, for good and for ill.

Faith is necessarily hard, but the bundle and shelf analogies for truth claim storage make faith needlessly harder. Life does not consist primarily of a logic game; it defines itself in community experiments and environments in cycles of growth and release—in sharing death and birth, reasoning and learning, experience and wisdom, suffering and grace. The shelf and bundle analogies may have occasional uses, but they also normalize static states of knowledge, cover appropriate uncertainty with false confidence, encourage fragile truth management, and approve of cognitive negligence. Neither analogy slows all-or-nothing, black-and-white thinking. Bundles snap and shelves break. In my search to cultivate truth, these analogies feel strained and bizarre, even alien. I simply don’t recognize them. To paraphrase Laurel Thatcher Ulrich here, be careful what you put on your shelf. Maybe avoid having one at all.

Regardless, we know the goodness and truth of a belief by its products, not its priors. Alma and Jacob make this clear in famous passages. So does William James, an exquisite crop rotator by another name: he invites our “looking away from first things, principles, categories, supposed necessities”... and “looking toward last things, fruits, consequences, facts.” Crop rotators cannot attend to every plant all the time, but we can observe them regularly and cyclically, weighing their growth and produce. For the ancients as well as for many today, the art of living faithful to truths resembles more of an anthropological orthopraxy than an epistemological orthodoxy. Living truth outweighs claiming truth every time; claiming truths may become a means for living truth, but the claim itself doesn’t mean the truth will never wither. To tweak the famous Francis of Assissi quote: live, don’t preach, the truth at all times. Use words if necessary.

Crop rotation comes with other advantages: limited resources cultivate managerial resourcefulness among farmers. No single variable makes or breaks a harvest, just as life cycles take place in complex environments. The crop rotator knows that rich harvests depend on their best efforts. Our labor, care, work, and cultivation all count, as do a host of factors beyond any individual or institutional agency. The annual harvest follows the climate, the weather, and the soil conditions of our faith and other communities. In rotating our crops, we let go of the myth of the solitary agent and let reality in. Explaining the world with a single variable is obvious folly, and even though we often benefit from controlling one variable at a time in our reasoning and experiments, clinging to only one variable to explain everything, or even any one thing, leads to probable drivel. My agency is insufficient to grow truth. I can plant a truth claim but I alone cannot force growth.

So what can we do to cultivate truth across many actions? Could we improve on these?

Don’t understand? Ask.

Cannot understand? Try.

Cannot try? Rest.

Periodically let go and give away your excess.

It is a mistake to isolate truth into a single subject position. Responsible action emerges from neither the agent nor the structure, neither the individual nor the social history alone. As Anthony Giddens suggests, perhaps action happens in the middle of agency and structure, and the environment emerges from the dash in every subject-object distinction. A scientist without peers resembles a prophet without followers; we need one another. Action is the crux of our collective cosmos. As the reformer and leader of women’s suffrage Jane Addams wrote, “action indeed is the sole medium of expression for ethics... civilization is a method of living, an attitude of equal respect for all.”

Crop rotation also suggests we organize our learning and lived practices away from steep cognitive cliffs and around ordered (if still rolling) fields. In surveying the fields of truth claims we possess, perhaps we might plant household management beliefs one year in this field, culinary arts in that field, historical learning in the next field over, scriptural learning in that field, philosophy and speculative arts in still another field, music techniques in another, etc. Different rules and uses govern different fields. Without first organizing our beliefs into fields, we cannot coherently rotate or give away their excess: crop rotators cultivate fields of learning and action greater than the truth in one’s head. Crop rotation rewards traditions and people who keep notes, records, and files.

Ordered fields of beliefs come with several advantages across time and space: temporally, they prompt prudent planning, management, and adaptation in the medium term, staying alert to the next quarter (business cycles inherit the farmer’s seasonal language), and rolling with the daily punches of weather, the caprice of rain and sun. (The German word for “bet,“ die Wette, resembles the word for “weather,“ das Wetter. What farmer refuses to make smart bets?) As Katie Lewis suggests, a field of belief may lose its crop without affecting the surrounding fields, yet the time I spend learning how to grow a new crop in that field may help me grow the other fields. For example, learning biblical criticism or literary analysis may allow some inherited crops to wither even as it also opens (often richer) possibilities in history, philosophy, and other inherited traditions of interpretation.

Spatially, fields may coexist peacefully side by side; rolling fields, unlike cognitive cliffs, do not stack against or collapse into another. Thus there is no contradiction if, say, fields of religion grow vegetables differently than fields of philosophy. For example, as my coreligionists may recognize, Nietzsche, the son of a pastor, concluded the same thing in secular Europe that the resurrected Jesus told the young man Joseph in a grove—that his church cannot be found here. That the atheist philosopher sometimes appears as a restoration philosopher should cause neither panic nor rash eurekas: philosophy and religion grow in separate fields. They are expected to have different purposes and only sometimes compatible claims. Worrying about either general crossfield contradictions (e.g., philosophy is antithetical to religion) and curious crossfield confirmation (e.g., a philosopher confirms a religious claim) misses the point of the harvest: we do not garden or farm to pit neighboring fields against or to align them with one another. No stale showdown, we organize our plots and fields to cultivate rich yields, abundant and diverse produce. We organize our knowledge so we have rich harvests of useful knowledge and ever-growing truth claims. Habits of patient evaluation, discernment, context, and judgment maintain and manage their many fruitful cross pollinations, irrigation ditches, and fences between fields. Our fondness for comparing apples and oranges does not make their tastes any less distinct or sweet. Let differences do their good work.

Worrisome claims should face calm evaluation—not panic, not obsession, not neglect. Encounter a troubling claim? Breathe, stand with dignity, step aside, and observe. Where am I encountering it? What effect does the claim have? How can I use my or others’ experiences to frame this truth claim in a better light? Is this claim worth my time right now, or should I tend to another field? Truths need never take root nor fail at once: each field can sustain many truth claims, and, as the experimental method in scripture and science both attest, the truth of each claim arrives by tasting its fruit at the end of the growing season.

So let’s welcome and organize different fields around different fruits. Of course contradictory fruits routinely spring from the same soil. Literature and physics, religion and philosophy, business and political economy. These fields sprout ample contradictory claims—thank goodness! If both claims offer useful fruits in their own separate fields of creation without harming others, they suffice. In other words, encountering a logical contradiction between belief claims need not compel either reactionary dismissal or immediate conviction. Contradictions, since they are also claims, should be evaluated under the same terms as their composite belief claims. Contradictions can point to other new fruit, not only backward to entangled causes and roots: what are the uses of this contradiction? Whom and how can it serve and harm? Who benefits and who loses when contradictions are studied, litigated against, or welcomed? We diminish the value of contradictory claims when we work backwards to prior causes, and not toward possible fruits: be wary of generalizing the mere existence of a contradiction or tension into invalidating the entire field that grew the offending claim. Instead, the value of a contradiction in claims holds that of any other claim: what good can a contradiction do? It makes up a fruit with uses, some better than others. And (for now) that’s just it. It’s the separate usefulness of claims that matters, not mere logical consistency between them. There’s no panic in meeting contradictions: let’s greet them, consider whom they serve, and connect them in ways that serve many more.

The reconciliation of contradictory fruit will not be clarified by searching for a single truth to explain all reality. That solemn fact gives all the more, not less, reason to continue searching for restoration and reconciliation: for reconciliation will not come through unearthing some primordial ur-cause but through pointing forward to more diverse growth, action, and consequence. The industrial crop rotator who surveys a verdant world and then expects it to grow one single truth, again and again, generation after generation, cannot succeed—for even if they do, they (and their biome) will grow awfully tired of, say, corn. Our species is naturally omnivorous, although we should stress plant analogies and the wisdom of eating meat sparingly; we thrive on a variety of healthy, fresh organic produce for our bodies and minds; and rich are the lives spent preparing community feasts using the full farmers’ market of different crops, contrasting tastes, and colorful cornucopias. Industrialized monocropping hurts as both a truth metaphor and an agricultural reality.

But, we might ask of the analogy, doesn’t a thoroughgoing crop rotation risk placing too much focus, even a possessiveness, on the results, fruits, or harvest of ideas? For example, couldn’t a critic to the crop rotation analogy simply point out that, say, almost every comic book villain becomes convinced that the future harvest of their intentions justifies lies, cheating, or even murder in the name of some perceived “greater good,” that they become, well, a comic book villain? “I’ll save the world,” cries every tragic figure since the beginning, “just you wait!”

Against such crude consequentialism, the crop rotation outlined in the Torah offers an elegant solution: regularly donate whatever it is we horde. We must serve the needs of others by regularly and periodically giving away our excess—the extra crops, our increase in wealth and truth, and the surplus consequences one has gathered. Even relatable villains and tragic figures struggle to do this too, so let’s recognize that each of us is engaged in our openly mortal struggle to give away our excess. Do not demand others take our excess (for we cannot yet know its value to them) but give it freely away we must. Crop rotation votes against hoarding silos of harvest wealth by inviting the periodic release of individual excess. In our world where about one percent of the population holds about half of the world’s wealth, this is the urgent law of shmita.

Crop rotation thus reorients our attention to consequence and collective benefit while also cautioning and legislating against living for possessive individualism and perpetual accumulation. It models methods of perpetual learning and growth while criticizing those who cannot yield its fruits to others. Beware of scholars (and their for-profit publication industries) who spend their lives building castles of knowledge for the sake of knowledge (or profit). Beware the wealthy who spend their lives building castles of wealth for the sake of wealth. All accumulators should regularly give away our excess without thought of reward, impact, or glory. Dickens’s Scrooge still casts a tragic shadow for how late in life he learned to give. Paraphrasing Michael Warner, every conversation today refreshes and gives away yesterday’s lines; so does every store of capital, owned by a few, accumulate the value made by many others. A debt jubilee twice a century (every seven times seven years) drives home the point: accumulation is not for the living. May every person have enough for their needs, no one have enough for all their wants, and our life on a living planet be sustainable.

When deciding how to give away surplus truth and matter, don’t make our own greatest good the law: the attitude that because I know how to get, I know how to give—or any other claim to my own greatest good—may be among the very excessive beliefs our society most needs to give away. I see no reason that a people skilled in material acquisition would be good at using that excess for others—and several reasons why it may be the opposite. Should not every mortal being anticipate rotating through and regularly giving away all excess and surpluses over the arc of life? It seems to me that we must let go of (let die on the vine) the beliefs and talents that do not do good work while also giving away for others to use the surplus of the beliefs that do work. Again, give we must but force our gifts upon no one—for we cannot know its value to them yet. I cannot tell how best to use the excess I can give away because its value does not depend on how I measure it. Its value depends on how others would use it. Societies must determine that question democratically and with expertise, so as we participate in the necessary scrum and costs of democracy, may each listen actively, give freely, let all who seek our excess take freely from it. Let the changing needs of the many guide our giving. Let no single good, no matter how pressing the present demand nor how altruistic or lofty its future (remember the comic book villain), possess or capture all the good our surplus stores can do. A mutual fund does this internally by diversifying and balancing goods across time and economic value; that mechanism works only until the fund consolidates into an idol of our desire. Accumulators must regularly give away so that goods never become the highest good.

Could part of giving away our excess also be giving away our specific desires for how and whom our excess will serve? Should we not ask inspiring questions, empower disinterested third-party means of distribution, listen to and entrust the needy? By engaging, serving, listening, and humbly acknowledging that we cannot know all future needs, crop rotation mounts a subtle criticism against the relentless long-term utilitarianism, whose most recent brand calls itself “effective altruism.” Crop rotation stands firmly against the monocropping of the future. It inspires and requires charity and giving without endorsing all forms of philanthropy.

Comfort and sorrow lie in how the seasons of life vary over the years. Crop rotation encourages us to anticipate and sit through seasonal variations in our personal lives, including the long cold winters of silence, the spring of fresh possibility and planting, the summers of growth and tiring sun, and the falls of harvest, feasts, and coming darkness.

Our fields of truth will sometimes appear barren (even evergreen trees appear like torched matchsticks after fires) and then at other times, anticipating the coming blaze, brim with overgrowth and kindling. It does some good to anticipate seasonal cycles: the variations of faithful living let us sit in the autumnal burn and the barren winter of our psyches with the hope that, with care and time, patterns of renewal and new growth will abide.

Every psyche I know rotates through its own nights and winters. The nightly fire clearing of our minds and memory that we call dreaming permits meaning and regrowth to follow in the daytime. The wintertime depressions of the mind and heart are real and hard; with time, sustenance, support, and rest, they sometimes pass. So do the celebrations of summer solstices and holidays at harvests. The crop rotator rests aware that, when the bitter winds die down, the sun will rise and the spring showers will fall: cultivators may pick up their tools, assess which beliefs to plant, learn the rhythms of our community’s lives, and anticipate what the next season will bring without fear or foolishness.

With seasonally fluctuating minds and bodies, we should not be too surprised that truth should appear no simple all-in or all-out proposition but a vibrant and robust maturation, or growth, made visible to the communities that develop it. As it grows or dies, truth claims need not collapse like shelves or break like bundles in sudden catastrophic failures.

Crop rotators, unlike shelvers and bundlers, have time and experiment on their side: they can slowly unbundle claims and plant them in their respective fields organized by, say, literature, history, art, music, and the sciences. Each row may in turn be given time, study, and seasons to grow, enriched by seasonal cross pollination with other fields that also bear fruit over time.

Rotators tend the fruit likely to grow from a claim, learn from experience and others, and welcome heartfelt criticism to better ends. Like a prudent gardener, they plant claims where they are most likely to grow, observe them and experimentally assess their growth and decay, nurturing those they seek to enjoy, and, upon observing variation, neither rashly rip out its roots nor spread its seeds. Plan, sow, observe, adjust.

The crop rotators did not create and do not own the harvest: humility, awe, and reaffirming commitment follow the acknowledgement that truth takes time and community. This essay, obviously, takes its time, but that does not mean it speaks the truth directly, of course. Rather we can set aside its content, and the careful reader will see it practicing a greater truth at work: reading interrupts reaction. The effects of sustained reading, the habits of patient work, and the slow approach of wisdom give the same gift: when we move carefully, we have a better shot at sorting the tares from the wheat, the tassels from the corn.

In other words, we recognize truth by its periodic results, not its roots or antecedents. It should surprise no one that some truth claims in my fields will shrivel while others will sprout. No one, not even the industrialized farmer, imagines that every plant will survive to the harvest or be given away in the sabbatical year. Doubt the cafeteria life—taking what we want among the prepared bits and ignoring the rest. Attend and find your place in the process. Perhaps each of us can attend to the crops that enter the cafeteria, confident that, as our communities work the gardens, fields, and kitchens that feed the flocks, pruning wilted plants speeds cultivation and growth too. It clears the ground for new experimentation next year. Every field of crop rotation I know both inherits unwanted baggage from other traditions and at the same time benefits by deliberately inheriting truth wherever it grows.

Crop rotation does not stay the course year after year; it invites regular experimentation in the short and middle term: without rotating one’s crops and periodically resting from and reevaluating the orderly care of truths in one’s life, the needy have no fields for gleaning, the rotator enjoys no sabbatical year, accumulation knows no limit in the jubilee, and the community has no surplus gleaned and gathered ready to give away after the harvest.

So far we’ve established that truth grows slowly. But what about action today? For, after all, if we can agree that all-or-nothing thinking falls short, then some “all or nothing” talk may still do appropriate work under specific conditions. In other words, not all “all or nothing” thinking should be discarded: this appears a necessary conclusion of doubting all all-or-nothing thinking! Namely, we can find seasons and situations in life when chains of overclear if-then syllogisms do help build easy onramps and offramps for guests onto the highways of any tradition of learning. For example, as a teacher entering a new classroom, I lay out a syllabus and introduce new learners to a field of belief claims in just a few words: of course teachers move quickly on day one, surveying the arcs in a syllabus paragraph or providing a quick overview of subjects and their interdependencies.

So much for the first day: on a good first day of class, each of us leaves like we once were—blind but now we see. But with time and patience, bundled truth and cognitive shelves may be safely set aside, unwound, planted, and cultivated alongside more robust vocabularies and semesterly seasons of deep learning. We study many subtopics enriching without impugning the whole. In each of our personal journeys of life, learning, and faith, the road to Damascus leads to, where else, Damascus: a space of complex, robust, bustling collective action. On day one, Saul enters and leaves as Paul, only to spend the remainder of his lifetime critically rereading, as each of us do today, his learning and epistles. There’s no fear here: truth, however else it may grow, rarely proves fragile, brittle, and unsustainable.

For crop rotators do not possess truth; truth possesses all of us—it feeds us, shapes us, it gives us purpose and fuel. Truth does not belong to me; rather we belong to it. For this reason, while celebrating personal witnesses, I rarely am moved by (or condemn) “my truth” and “the one and only truth” claims because both assert of and from the self. In so far as these statements help me and others serve and cultivate greater living truths with others, so be it. But after day one in class, I find truths that depend on whether I declare them true far less moving than those truths that so move me that I cannot help but declare them through me. I welcome a life arc that would transform me from a subject that seeks to act upon the world over time into a dynamic object for truth to act upon. Could there be a higher calling? May we gather, read, talk, and learn six years long not to influence others but to seek out the best of other influences; on the seventh, may we write not to persuade but to freely give away what moves us.

Truth exceeds the self; it requires no self-help solutions; it holds because of something general about itself—its worth in every particular application. Truth is that which works better and better, accumulating collective consensus and value not among the self, not among just one gender or one group, but among all, as the short-term ever unspools.

What else could it mean to be true to reality except for truth to be that which works in increasingly many conditions over time? What condition of truth could ever supersede a sustainable, variable, emergent pattern of good? Nothing could be so certain, if also (trickily) unknowable until after the fact. That we cannot know the truth until after the fact sounds defeatist and tragic, and, in a sense, it is but that sense is narrow. More broadly, the tragedy lies with us, not truth. Our efforts may fail—individuals and societies stumble, suffering may go unrequited and unheard, the wind and blight rage, civilizations rise and fall in geological blinks of an eye—and still faithfulness to truth will endure, with or without us, because truth works.

PART TWO

Benjamin Peters is a Wayfare Associate Editor. He is also a media scholar, author, and editor interested in Soviet century causes and consequences of the Information Age.

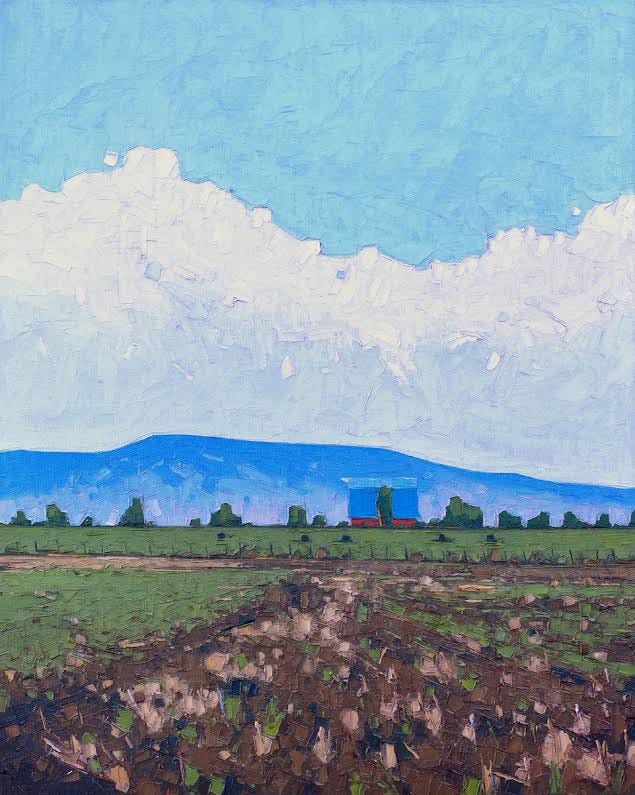

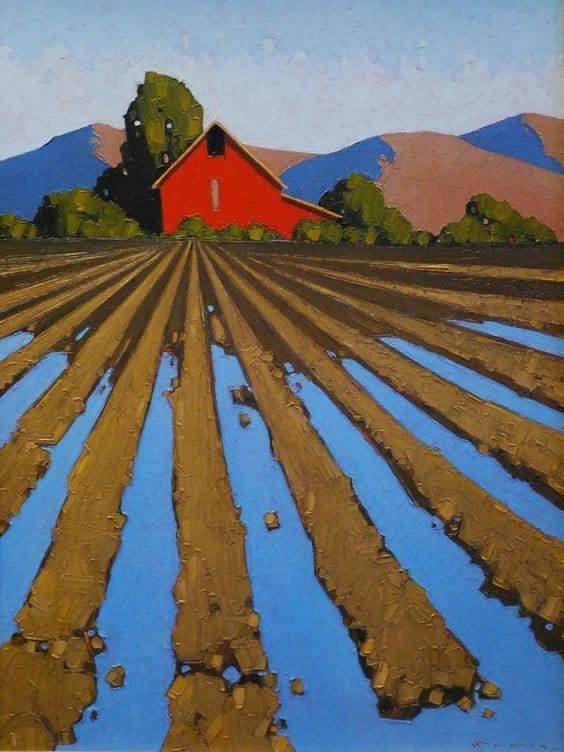

Artwork by Jeffrey R Pugh.