McKay Coppins’ Romney: A Reckoning is a thoroughly Mormon book.1

On the one hand, this is obvious. The book was: primarily researched by a church member (Samuel Benson), written by a church member (Coppins), and has as its subject the faith’s most famous member, a man who has dutifully served as a missionary, bishop, and stake president.

It's hard to imagine a book that would be more Mormon on the surface.

But the Mormonness of the work goes far beyond that.

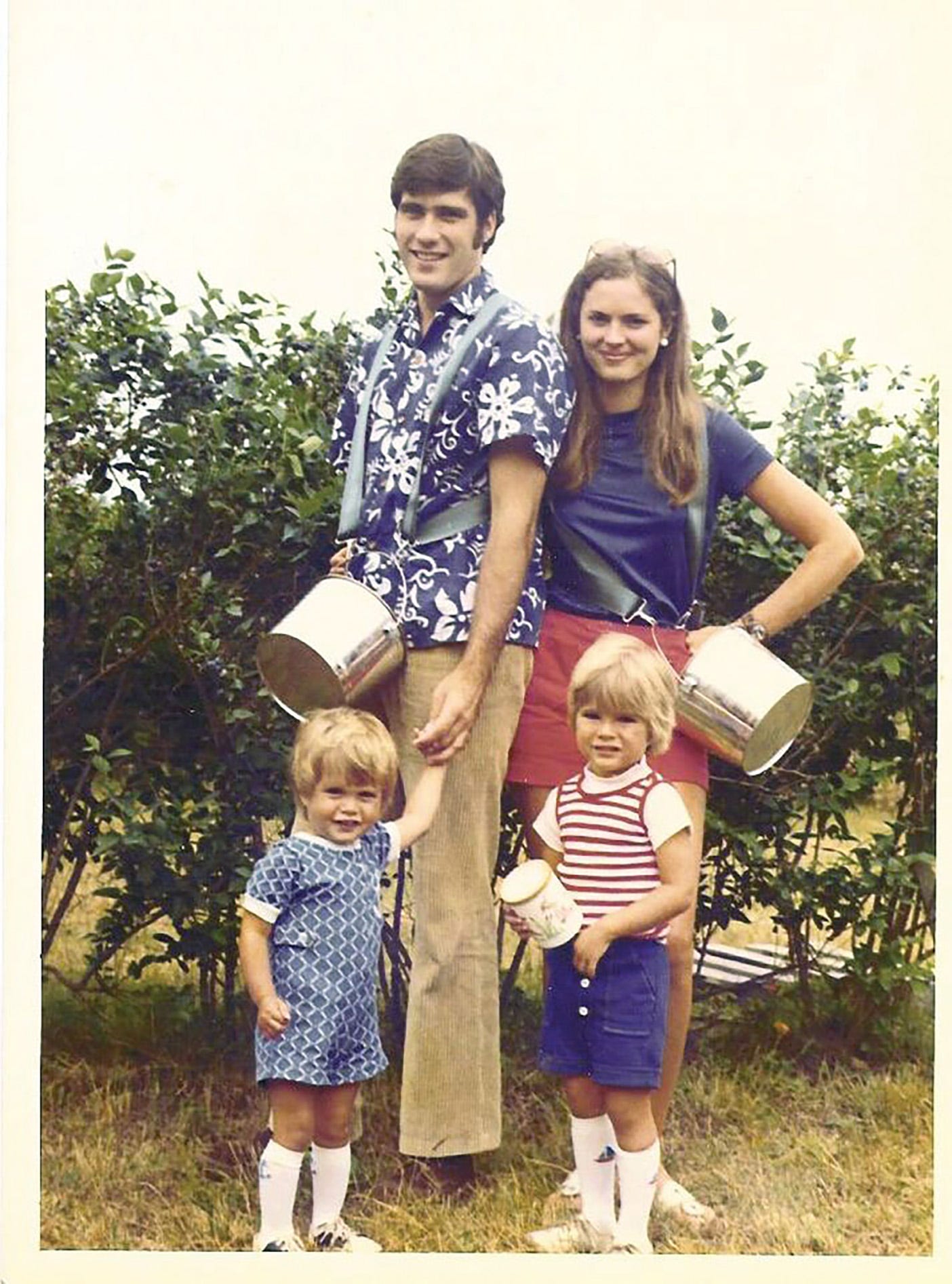

For example, family constitutes one of Mitt’s overriding concerns—almost an obsession. Church members talk often about the prophecy that the “hearts of the children would be turned to their fathers, and the hearts of the fathers would be turned to their children.” And for no one could this have been truer than for Mr. Romney, who cherishes his family’s esteem and who never stopped looking to his father’s legacy as his moral lodestar. Likewise, Romney’s political outlook reflects the mix of sunny—almost naïve—optimism and scruffy pragmatism that are two of his faith’s chief virtues. Similarly, both Romney’s moral blind spots (he seems untroubled by his immense personal wealth, for example) and his most noble virtues (his willingness to go it alone when convinced his cause is worthy) reflect moral concerns central to his faith. Finally, the book’s deeply personal details derive chiefly from Romney’s faithful journaling, another hallmark of his faith.

All to say: in its entirety, the book deeply reflects Mr. Romney’s religion in just about every facet.

At the same time: Mr. Romney cannot stand as a universal avatar representing all members of his faith. Most church members are not Ken-doll-esque multimillionaires who mount repeated campaigns for the world’s most important political office. Indeed, most of the church’s members (including all women and all people who are not married) never serve in the leadership positions that came to Mr. Romney so early. Likewise, the church’s members span the political spectrum and significant evidence from Jana Riess, Jacob Rugh, and others demonstrates that the membership is becoming more politically diverse, especially younger members (though whether this apparent change will endure into those young members’ later years remains an open question). Indeed, it is amusing and slightly surprising to learn toward the end of the book that not one of Mitt’s five sons now identifies as a Republican. Finally, Romney is a wealthy, well-educated, white, straight man who “checks all the boxes” and has therefore had a much easier road than anyone who identifies differently within the church.

So, let’s stipulate all of that, as well.

But still: aside from superficial similarities, I would like to posit here that the book strikes a deeply important chord for this reason: because Mr. Romney’s central struggle represents the existential decisions facing our church in 2023—a struggle I believe will largely serve to define the shape and course of the church as we enter the second quarter of the 21st century. As I listened to the book, this was the theme that weighed most heavily on my heart.

The book’s central moral arc—and what seems to be the defining struggle of Mr. Romney’s political life—is simply this: what is the role of accommodation in the moral life of a politician?

First, we must guard against our reflexive tendency to shout “accommodation is evil!” This is not true, for both moral and practical reasons. U.S. politics has, over the last quarter century, especially, become increasingly polarized. Many forces drive this polarization, but one of the most important is the increasingly accepted belief that, in the political arena, any compromise is bad. As both major political parties have retreated into increasingly-cocooned media spaces, it has become easier to demonize one’s political opponents. A wealth of data demonstrates this. This demonization makes compromise virtually impossible: if my opponent is mistaken but well-intentioned, then compromise and the necessary give-and-take are just part of doing political business; if my opponent is actually evil—if she or he doesn’t even want what’s best for the country—then any “give” on my part is not compromise, but capitulation.

Thus we end up forever like Dr. Seuss’s “Zax,” who, when they meet going opposite ways on the road, remain forever frozen facing each other because neither will move to one side.

This is all to say: compromise and accommodation are not just necessary, but morally good. We want our politicians to compromise. We want those who represent us to be willing to give in in the name of accommodation. We need those who work in government to strive to see the good on all sides of an issue, to look for common ground, and to be willing to give and take. For church members who believe I am mistaken, I would point you to President Dallin H. Oaks’ 2021 address at the University of Virginia. This speech came as a surprise to many listeners but, in fact, reflects Pres. Oaks’ approach to similar issues over many years. In the address, he makes a thorough, nuanced, and deeply theological argument supporting the need for accommodation in the public square. Restating his entire argument is not my intent, but he summarized his view succinctly when he said: “Good faith negotiation invites that seldom-appreciated virtue so necessary to democracy: tolerance, free of bigotry toward those whose opinions or practices differ from our own. Far from being a weakness, reconciling adverse positions through respectful negotiations is a virtue.”

Thus, for both practical and theological reasons, compromise and accommodation can be a genuine moral good.

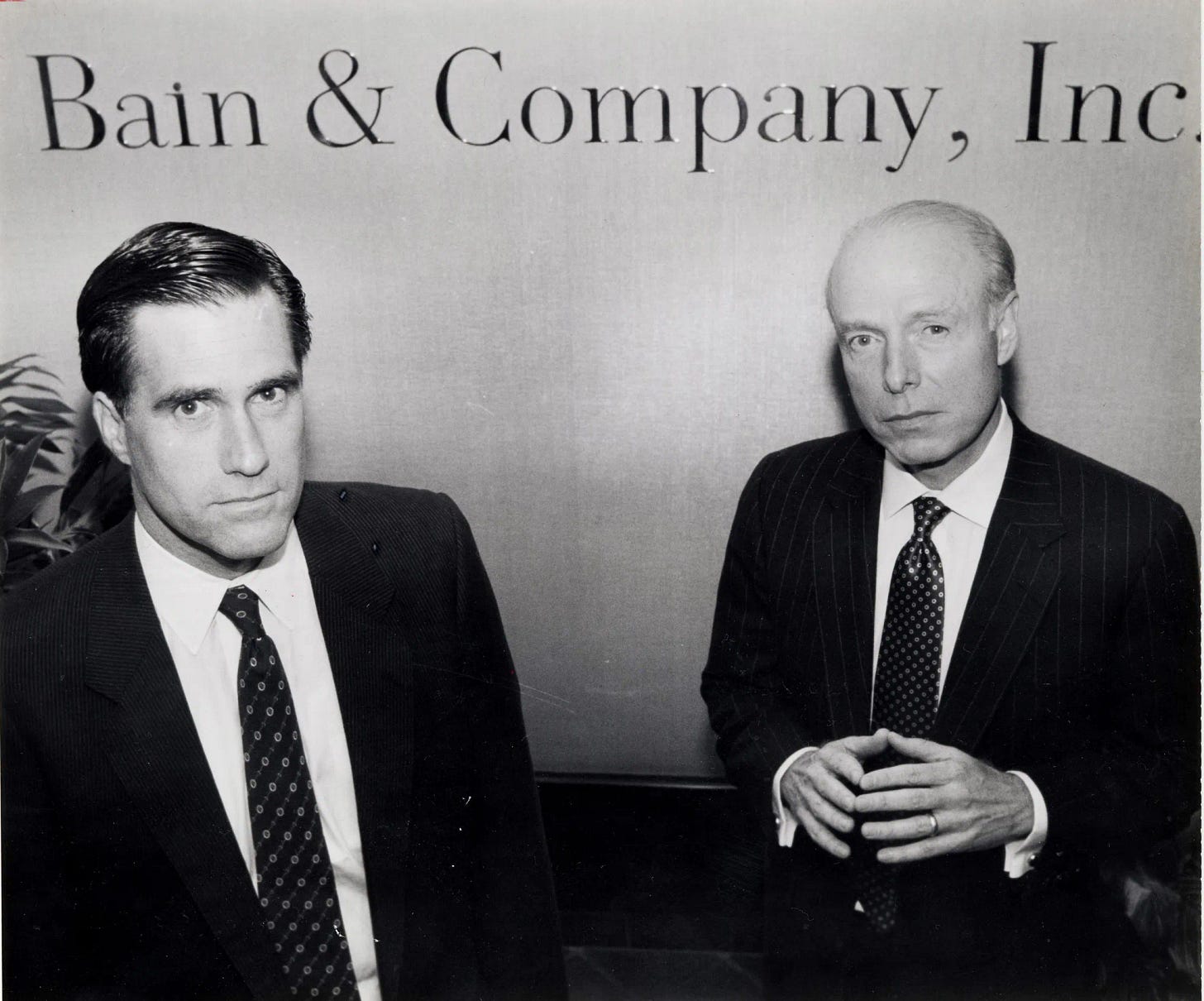

That said, however, there is no question but that this is also true: Romney: A Reckoning does not derive its moral heft because it demonstrates the astute ways in which Romney was willing to barter things away as part of the give-and-take of politics. Rather, sketched briefly, the story of Mitt Romney’s political career goes something like this: at a young age, Romney felt a sense of obligation to achieve something great in the world and felt called to go into politics. He spent the first 18 years of his political career (from running to take away Ted Kennedy’s senate seat in 1994 to running to take the presidency from Barack Obama in 2012) leaning heavily into accommodation. A critic would say he was a feather to wherever the political winds were blowing; a supporter might say he was ideologically flexible in the name of winning office to get important things done. Regardless, he was something of a political chameleon. When he ran in Massachusetts, he made himself a liberal Republican who once claimed to be more supportive of abortion rights than Mr. Kennedy, and when he ran for the presidency he made himself out to be “severely conservative,” including wince-inducing gaffes like trying to endear himself to the gun rights crowd by crowing about how he just loved to hunt “varmints.”

But then, the dawning of American authoritarianism in the form of Donald Trump shook awake the better angels of Romney’s nature. He was no longer a chameleon but, instead, became a gadfly and then pariah who staged a remarkable instance of what Mr. Coppins calls “political repentance.” He forthrightly spoke his mind, stood against the President’s amorality, lawlessness, and authoritarianism, and refused again and again to give in to those who attempted to change his mind. Romney’s late career independence results in a vote to confirm Justice Ketanji Brown to the Supreme Court and, most famously of course, in his willingness to vote twice to convict Mr. Trump of impeachable offenses—the only senator ever to have done so against a president of his own party. When he met his Richard Rich moment—and though he salivated after his own personal Wales—his integrity held and he stood up for truth and did what was right.

Thus, the arc of Mr. Romney’s moral journey bends toward integrity. It is his willingness, in the final analysis, to stand up for what he genuinely believes is right—in a political context where there was often no reward for doing so—that wins us to his cause.

So why does all this matter to us as regular church members, most of whom will never belong to a school board, let alone hold high political office? Because our faith stands in a position that reflects, in some important respects, Mr. Romney’s fraught position over his three decades in politics.

In 2017, Patrick Mason came to Stanford University and delivered an address entitled “Mormonism’s 3rd Century.” In it, he argued that our first century was a struggle to simply survive. Our 2nd century was a struggle to integrate (into American culture, mostly) and become accepted. And that it would be in our third century that we would be able to genuinely contribute to the world some of the peculiar theological, cultural, and practical gifts that have come to us through the restoration.

I applaud this formulation but want to emphasize an aspect of his framing that differs slightly from where he focused those years ago. From my vantage, the important precursor to asking what we can offer to the world is this: in the name of cultural accommodation, and in a quest for cultural or theological acceptance, have we already given too much away? In hopes of increased social or political power, or simply because we want other people to like us (an abiding and understandable concern for a people too long accustomed to being outcasts and a byword), have we tried too hard to conform to the expectations of, for example, evangelical Christianity or the far-right wing of the US Republican Party?2 And if so, what have we lost?

Now, it might be easy, when weighing these concerns, to turn our focus to our religion’s leaders. I have read essays, for example, pointing to J. Reuben’s Clark’s “The Chartered Course of the Church in Education” as the beginning of a turn toward doctrinal fundamentalism. Similarly, many will point toward the early words of apostle Ezra Taft Benson—who was unbashful about promulgating right-wing political stances as necessary constituents of gospel life—and point out that he directed many church members toward the conservative end of the political spectrum.

But I think a focus on these leaders is insufficient for multiple reasons. First, while their legacies no doubt loom large and the cultural shadows they cast are no doubt long, both of them (and most others like them) dwell firmly in our past. Second, because our current leaders (as with President Oaks above) have made it clear that we are not to press firmly or uniformly in any one political direction (President Oaks Easter 2022 General Conference address is even more explicit on this point). Third, because the institutional church today officially represents practices and beliefs that fall all across the political and cultural spectrum: we might easily cite views on marriage and family as proof that the institutional church remains rooted on the right, but a review of the church’s stance on the treatment of immigrants or on our stewardship for the environment make it clear that this is nowhere near uniformly true.

But the most important reason is simply this: the majority of what actually happens in the church, for good or ill, is done by regular old, everyday, non-leadership church members. Indeed, in this regard I’m reminded of the observation from Neal A. Maxwell who once said: “For what happens in cultural [change] both leaders and followers are really accountable. Historically, of course, it is easy to criticize [...] leaders, but we should not give followers a free pass. Otherwise, in their rationalization of their degeneration they may say they were just following orders, while the leader was just ordering followers.”

All of this is to say the following: when I consider together Patrick Mason’s formulation of where we have come as a people and the moral arc of Mr. Romney’s political career, I am led to ask: in what ways have we abandoned the birthright of the full splendor of restoration theology for the mess of popularity, “being like folks,” or trying to win and wield political power?

Our theology is clear, for example, that the Earth was made to be beautiful, and that we are its primary stewards—yet what do we do to honor these fulsome beliefs?

Our theology emphasizes that all humans are children of loving Heavenly Parents: are we yet known as the staunchest defenders of universal human rights? Are we the most likely to welcome immigrants? Are we the readiest, as Linda K. Burton once invited, to ask “what if their story were my story?”

Our theology offers deep and abiding ways to explore the meaning of human suffering, are we the first to ease the pain of those who suffer?

Our theology and history equip us uniquely to understand the plight of the ostracized, the forgotten, the marginalized, and the oppressed, but do we always stick up for those who are at the margins?

Our scriptures insistently decry materialism, but are we yet known for eschewing material concerns in furtherance of the common good?

Our theology preaches consistently that the glory of God is intelligence and admonishes us that that which we learn will rise with us, even in the resurrection, but do we yet act as if we truly understood the weight of these teachings?

Our theology imbues our view of the mortal condition with a sense that is at once exalted yet deeply tragic, but is this fully represented in the art we create and the music we make? Likewise, have we abandoned the most compelling and revolutionary aspects of our theology—as the Givenses have suggested—in pursuit of a theological approach and vocabulary that will ruffle fewer feathers?

Our theology steals our breath with its literal insistence on our staggering potential but do we yet rise to the full stature of behavior that such an idea would require?

The Book of Mormon could not be clearer in demonstrating that the “promised” status of the United States only finds meaning insofar as we abandon caste systems, abolish all types of -ites, alleviate poverty, and ward off pride in every form, but are we too easily enticed by the central idea of Christian nationalism that says that might makes right and that the US is great because it is powerful?

Our theology centers the importance of both community and family, and gives stunning theological support to both notions, but do we fully support both local and national political policies that would support these two vital entities, rather than making them more difficult, especially for people of few means?

This is not to say that any or all of these ideas offer easy answers about how to navigate the complex waters of mortal life. Nor do I mean to suggest that any or all of this suggests some facile political program with answers to the complex problems of society. Nevertheless, I do worry that we simply care too much about being part of the “in crowd.” In this way, to channel JB Haws, we too often seem like a teenager on the world stage, worried so much about being “popular” that we are forever unable to live up to the lofty potential inherent in what we believe.

Among the congregation to whom I am preaching here, I first include myself: I keep too much of what I earn. I become distracted by things that matter less. I care what others think about me. I want to be seen as being good and smart—and often worry I prize my appearance of being good above the actual content of my character.

All to say: I am far from perfect.

But in that sense, I will look to Mr. Romney as an example—not because he was perfect, but precisely because he was not. His early imperfections, especially, round him out as real and believable when he tells Mr. Coppins, in an anecdote recorded in the book’s epilogue, that he now routinely tells aspiring young people that they must be sure “not to sacrifice integrity on the altar of ambition.” I am not sure precisely what my ambitions are—to be seen as smart? To be well-liked? To be admired? To make a difference? To be regarded as kind? And I am even less sure how we would collectively articulate the ambitions we have as a church—to belong? To be taken seriously? To rise to the top? To expand? To have cultural power?

But I do know this: to the degree we sacrifice living up to the full power of our theological convictions in the name of achieving these lesser ends, we fall far short of our potential as a people, and the world is the poorer for it.

Tyler Johnson is a Wayfare contributing editor and an oncologist and Clinical Assistant Professor at Stanford University.

Normally, I defer to the literary convention requested by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as articulated by President Russel M. Nelson, to avoid this term as used here. In this case, however, I will not adhere to that conventions for multiple reasons. First, Mr. Coppins’ books uses the term ubiquitously, so it seems in keeping with the spirit of the work to use the term in a review proceeding from that book as a foundation. Second, I refer here not so much just to the religion of which Romney is a member, but, rather, to the entire set of cultural mores, historical forces, and, yes, religious tenets contained within that church and familiar to anyone who is a member of it. And, I confess, even after a number of year writing with the intent to avoid that term, I simply have not found another that quite conveys that entire set in of things in the same way. Finally, most of the history that is articulated in the book took place when the term Mormon was not only common, but viewed with a certain affection by most of the faith’s members (eg the “I’m a Mormon” campaign).

In theory, we could ask a whole host of such questions: are we too tempted to align ourselves with Catholic teachings or are we seduced too often by the far-left part of the political spectrum? But while such concerns might hold weight in this or that specific aspect of our culture, those would be very much the exceptions, not the rule.

This is very well done. Thank you for writing it. I agree that the Church and, more particularly, its members are at an inflection point. And while some Church leaders may be willing to compromise on some matters, the membership in the American west appears beyond compromise. They have thrown in with the hard-right edge of the Republican Party egged on to a significant degree by Church leaders in the push for Prop 8. I question whether even Church leaders can bring them back from the brink at this point. They are, as Mr. Romney has learned first-hand, well to the right of Mr. Romney, who they consider a traitor. As a generalization, they are more (Trump) Republican than Mormon. I hope I’m wrong. Thank you again for your thoughtful review.