Revelations of Divine Love

Approaching Infinity with Julian of Norwich

I didn’t have a strong reason for visiting Norwich, England, last October. The medieval city is often overshadowed on tourists’ itineraries by charming places like Oxford and Brighton. But I wanted a short getaway before beginning a master’s program at the University of Cambridge, and Norwich was nearby and seemed interesting enough.

The first place I visited was the church of St. Julian, a modest pebble in comparison to the mountainous Norwich Cathedral. Unlike the other churches dotting the city center that boasted towering spires, intimidating stone, and intricate ceiling carvings, the church of St. Julian was unassuming. In a word, it was quaint: cobblestone walls beneath neat rows of shingles, sloping predictably in an inverted “V,” and small windows of unstained glass.

Inside, I found a small chapel with a capacity for maybe fifty people, plain white walls, and an altar draped in forest-green velvet. On a table near the entrance was a stack of paper, hand-cut into strips not unlike the quotes I’m sometimes asked to read aloud in Relief Society. I took one, reading the following:

In this vision he showed me a little thing, the size of a hazelnut, and it was round as a ball. I looked at it with the eye of my understanding and thought, “What may this be?” And it was generally answered thus: “It is all that is made.” I marveled how it might last, for it seemed it might suddenly have sunk into nothing because of its littleness. And I was answered in my understanding: “It lasts and ever shall, because God loves it.”

The words were attributed to Julian of Norwich, a fourteenth-century mystic and anchoress at the church of St. Julian. Her real name is unknown, so she is typically referred to by the church’s name. As an anchoress, she lived a portion of her life (at least twenty-two years, according to scattered surviving sources) “anchored” to the church in prayerful solitude. She lived in a small cell attached to the nave, from which she never emerged—although a tiny window about the size of a mail slot allowed her to watch mass and receive the eucharist. A servant would have brought her food each day. Perhaps in her cell there was a window to the outside world where she received visitors.

The church I was standing in was not the same church in which Julian lived over six hundred years ago. Her cell was destroyed sometime in the sixteenth century, and the remainder of the church gradually met the same fate. Through the centuries, walls and windows crumbled, collapsed, and were reconstructed; a bell was fashioned on the church’s tower; and different elements of the building were repaired in isolated restoration projects. During World War II, the church was bombed and destroyed, necessitating a complete rebuild. Nevertheless, I felt a deep sense of the sacred in that humble patchwork church.

Visions in the Wilderness

This wasn’t the first time I had encountered Julian of Norwich. Two years previously, I had read her work in a medieval literature course at BYU. Her Revelations of Divine Love is a record of sixteen powerful visions that she had when she was about thirty years old. The visions occurred one after the other on a night when she was awfully ill. Once she recovered, Julian recorded her visions, which she called “shewings,” in what is now called the “short text.” Undoubtedly, her occupation as an anchoress compelled her to meditate and expound upon her visions—two decades later, she produced the “long text,” a more meticulous version of what she had composed previously, with extensive theological commentary. The short and long texts together became the Revelations of Divine Love.

My first impression of Julian of Norwich was somewhere between awe and incredulity. I found that her visions shared common elements with other familiar theophanies: like Nephi, she saw the Virgin Mary and the crucified Jesus; like Moses and Joseph Smith, she struggled against the devil; and like Alma the Younger, she was transformed by God's immense mercy. Her Revelations are flooded with unapologetic declarations of a God who endlessly loves us. And Julian, like other prophets in and out of the scriptures, felt an urgency to share the things she saw (and it’s a good thing she did—hers is the earliest surviving work in English written by a woman!).

Julian’s words were a cascade of truth that profoundly resonated with me. But as pleasantly startled as I was by her Revelations, my mind seemed to slide into questions about their legitimacy. I knew these questions didn’t stem from how her words settled in my heart—I was inspired and enlightened by her visions—but rather how they seemed to stir things up in my mind. Julian lived during what Latter-day Saints call the Great Apostasy. Then how could she have seen Jesus and spoken with God? Better yet, how could she have so eloquently described a vision of three heavens, a doctrine I believed was unique to my faith? I even felt some discomfort about her gender. Nowhere in any of my religious studies had I learned of a woman who had prophetic visions to this extent. Would it be a greater blasphemy to call her a prophetess or to deny the palpable prophetic quality of her writings? I wanted to believe Julian, and I also wanted to believe in an apostasy. I just didn’t know how. So, unsure how to proceed, I placed this cognitive dissonance on a high shelf in the corner of my mind, among other Questions I Will Ask God One Day, and forgot about it.

An answer snuck up on me about eighteen months later while reading Fiona and Terryl Givens’s book All Things New: Rethinking Sin, Salvation, and Everything in Between. After highlighting several prophetic figures who lived after Jesus and before Joseph Smith (including Julian of Norwich), they suggest that we soften our definition of apostasy “from total eclipse to wilderness refuge”. Perhaps it’s better to think of the apostasy as a period of time in which the Church was “in the wilderness” and the Restoration as the process by which the Church is gathered and brought out of exile. In this line of thinking, the Restoration didn’t reinstate something that had been wiped off the face of the earth; rather, it brought the Church out of the wilderness, picking up pieces, filling in gaps, and recontextualizing gospel truths.

This reframing allowed me to reconcile Julian’s Revelations of Divine Love with the Great Apostasy in a productive way, strengthening my belief in both. When I returned to Julian a second time in Norwich, I felt a surprising connection to her. A reverence. Whatever had kept me from fully appreciating her work before had since evaporated. This time, her Revelations struck me with greater force, urging my spirit in new directions.

At the Foot of the Cross

I ducked under the Romanesque door to enter Julian’s reconstructed cell. It was as plain as the church, with a simple altar beneath a wooden carving of Jesus on the cross. On one wall, the closest to the nave, was a shrine dedicated to Julian where visitors could light candles in tribute to her. Above the shrine was a stained-glass window depicting Julian kneeling beneath a crucified Jesus. At the time, I understood the image to be a metaphor capturing Julian’s devotion. Only after I purchased a copy of her Revelations on my way out of the church—with the intention to read them more thoughtfully than I had in my busy BYU years—did the nearly literal meaning of the stained-glass image become clear to me.

In her Revelations, Julian witnesses Jesus’s crucifixion and death as if she were present on that devastating Friday two thousand years ago. The excruciating detail in which she relates the Passion is perhaps the most evocative element of her work, including her striking descriptions of Jesus’s broken body—“the sweet skin and the tender flesh, with the hair and the blood, was all raised and loosened from the bone, and where the thorn tore open the flesh in many places, it looked like a cloth that was sagging, as if it would soon have fallen off”—and his bleeding head—“The great drops of blood poured down in globules from under the garland, seemingly from the veins; and in their coming out they were brown-red, for the blood was very thick; and in their spreading out they were bright red.”

In my Latter-day Saint upbringing I had never encountered such uncomfortably realistic descriptions of the crucifixion. I wanted to skip over them in embarrassment and focus more on abstract theological discussions. But Julian saw a purpose, even a necessity, in observing these “horrifying and dreadful, yet sweet and lovely” images from the foot of the cross: all who seek redemption must understand the Savior’s suffering and death wholly and intimately. Like other devotional texts of the late medieval period, rife with graphic depictions of the crucifixion, Julian’s Revelations invites people to experience the infinitude of the Passion.

In the Book of Mormon, Amulek teaches that “there can be nothing which is short of an infinite atonement which will suffice for the sins of the world” (Alma 34:12). Associating the Atonement with infinity can help us better understand the scope of Jesus’s redemption and salvation. Infinity cannot be encompassed within a mortal form, neither can it be beheld with mortal eyes. Yet, Jesus suffered the Passion in his mortal body: “how sore you know not, how exquisite you know not, yea, how hard to bear you know not” (Doctrine and Covenants 19:15).

But there must be some way that we can represent this suffering, however clumsily or inefficiently—some way to evoke infinity in a manner that moves us. Otherwise, we are left with a minimized notion of infinity, rendered two-dimensional in our sheer inability to understand it. In describing the indescribable—the infinite sacrifice of the finite, human Jesus—Julian’s morbid narrative gives a taste of what infinity entails. This illuminates an essential truth: Jesus is the bridge between the finite and infinite, between mortality and immortality, and between corruption and incorruption (see 1 Corinthians 15:53–55). Julian writes that we must journey onto an infinite plane in order to fathom how much Jesus loves us:

I saw in truth that as often as he could die, so often he would . . . truly the number of times was more than I could grasp or imagine, and even my mind could not comprehend it at any level. . . . But to die out of love for me so often that the extent surpasses man’s reason, that is the highest gift that our Lord God could make to man’s soul.

It is in the infinity of the Atonement of Jesus Christ, and the utter incomprehension of his sacrifice, that we comprehend his love for us. At the foot of the cross, all children of God can “eternally marvel at this high, surpassing, inestimable love that almighty God has for us.” His infinite suffering and infinite love are not mutually exclusive: To behold his suffering is to behold his love.

Julian wasn’t there that day at Calvary, rubbing shoulders with the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and other disciples of Jesus. But she didn’t need to be there. An infinite Atonement means that none of us need to be there to experience divine love. At the same time, an infinite Atonement means that all of us need to go there, spiritually, at some point—not to gain divine approval but to discover a forgiveness that has always been there. Julian’s Revelations prompted me to imagine, for the first time, what it truly would have been like to be there. To “view his death” (Jacob 1:8) in its most gruesome and realistic form. To place myself among the few who stayed near and watched his life drain out of him that night. It may be impossible to comprehend the infinitude of the Passion, but Julian took me closer to infinity than anyone else.

“I Shall Do Nothing but Sin”

I quietly left Julian’s cell, wandering back to the table near the entrance of the church. I took a copy of Revelations of Divine Love available for purchase and found a seat in the nave, thumbing through the pages. For twenty minutes, I opened to random sections, reading a few pages before flipping someplace else while other visitors milled about the tiny church, taking pictures by the altar and sauntering into Julian’s cell.

In Julian’s twelfth revelation, she says, “I often wondered why by the great foreseeing wisdom of God the beginning of sin was not prevented: for then, I thought, all should have been well.” Bear in mind that Julian has just witnessed in vision Jesus’s crucifixion and death, an experience so visceral that she deemed it the worst pain she’s ever felt. Thus, this question about the necessity of sin isn’t just about sin as a barrier between humanity and God; it’s also about sin as the currency with which Jesus’s suffering is measured. In other words, why couldn’t we have just not sinned so Jesus didn’t need to atone for all of us?

God’s answer to Julian speaks volumes in its simplicity: “It is necessary that there should be sin; but all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.” In this response, God’s saying, “Don’t worry too much about sin or the state of your soul. In the end, everything will be okay. I’m going to take care of you. You will be with me.” This “all shall be well” refrain shows up consistently throughout Julian’s Revelations.

One of the most beloved Book of Mormon scriptures is 2 Nephi 2:25: “Adam fell that men might be; and men are, that they might have joy.” It’s a catchy, feel-good passage teaching that Eve and Adam’s fall didn’t destroy God’s purposes. The fall is why we’re all here, and we’re supposed to enjoy being here! However, too often this verse is quoted in isolation, yielding only a partial understanding of Lehi’s point. If we continue into verse 26, we obtain a more complete picture: “And the Messiah cometh in the fulness of time, that he may redeem the children of men from the fall.” The fall of Adam and Eve is essential for the plan of salvation, but it is not our salvation. Jesus is our salvation. Without Jesus, Adam and Eve’s sin is irredeemable. Without Jesus, there is no joy.

Like Lehi, Julian discusses the Fall and the Atonement in tandem: “God’s Son fell with Adam, into the depths of the Virgin’s womb . . . to excuse Adam from blame in heaven and on earth.” That reconciliation in heaven and earth is the testament of God’s love for us: we can be free from blame not just on the day of judgment but also today. Sin makes space for redemption and carves out a capacity for joy—and we can feel that here and now. Eve and Adam understood this, noting that were it not for their transgression, they would never have known the joy of redemption—a joy which can be felt in this life and in eternity (Moses 5:10–11). While the fall of Eve and Adam bears eternal consequences, its effects are only temporary because of Jesus Christ: spiritual and physical death can both be overcome through him.

Julian understands her fallen state, but she is not deterred or ashamed. She says, “I shall do nothing but sin, yet my sin shall not prevent his goodness from working.” This passage is powerful and beautiful, but it generates significant questions. How does someone qualify for God’s blessing? Is it not true that God “cannot look upon sin with the least degree of allowance” (Doctrine and Covenants 1:31)? What does it take to be saved? At first, I thought this was some kind of divine paradox. But then I saw that it was only a misunderstanding of God’s true nature. Is God’s desire to save humanity sparked only by the kindling of piety? Did Saul’s sin prevent God’s goodness from working? What is God’s goodness, if not to save us from despair, fear, pain, and sin?

Julian shifts the focus from blame and shame to hope and faith in Jesus Christ. She acknowledges that living a sinless life is impossible but stresses that God doesn’t demand sinlessness. This isn’t to say we are meant to remain in a state of sin, but rather to emphasize that God doesn’t want us to become too preoccupied with our failures. Sin is a temporary fixture in our mortal existence, but Jesus has made a permanent dwelling in us, an eternal connection and redemption with our souls. Because of him, God’s goodness is not just within reach; it’s within us. Like the Israelites in the wilderness, we only need to turn our heads, to look and live. This suggests a reframing of reconciliation: Sin doesn’t separate us from our Heavenly Parents; it only prevents us from seeing them.

But sin is still sin. It causes pain, it fills us with remorse, it complicates relationships. However, the suffering that stems from sin is not to punish us. Rather, it’s to carry us to Calvary. And once we are there (and we all deserve to be there), by the immediacy and infinity of the Atonement, our pain is displaced by comfort and our sins erased. Thus, our sin-induced suffering is only temporary, a brilliant juxtaposition against Jesus’s infinite grace. Paul expresses this paradox beautifully, saying, “where sin increased, grace overflowed all the more” (Romans 5:20).

Sometimes, I forget that sin is what’s temporary and redemption is what’s endless. I mistakenly imagine that Jesus extends forgiveness in carefully measured portions that only last until I sin again. But when I realize that “I shall do nothing but sin” and at the same time I understand the impermanence of this sinful state, then I can “sing the song of redeeming love” (Alma 5:26)—because his love is greater than my sin ever was, or ever will be.

Closer to Infinity

Although I spent a total of maybe forty minutes at the church of St. Julian, I have thought about her almost every day since then. I went home with a copy of her Revelations of Divine Love, which I’ve studied carefully over the last six months. I have also held onto that flimsy paper with the quote about the hazelnut.

If Julian’s Revelations had one message, it would be that of God’s love. Indeed, that’s what she’s trying to say with the hazelnut metaphor: we are so small that we can fit into the palm of God’s hand, but God still loves us, and that love endows our existence with significance. Julian’s Revelations were a call for me to simplify my faith at a time when I desperately needed to do so. In that simplification, I experienced a flood of relief simultaneous with a surge of enthusiasm—both inspired by God’s love for me.

Julian’s visions offered me a new perception of God. The deity she described didn’t coincide with the deity of my understanding: a God who demands justice, a Savior who pays my debt, a Spirit that departs when I do wrong. Julian’s Godhead was different. She spoke of a God who wants to save me, a Savior who inspires me to worship God, a Spirit that never leaves, because God’s love is endless. At one point in my life, I would have shaken my head at Julian’s approachable, merciful Trinity—if her characterizations were true, then salvation became too easy and sin too accessible. But at this particular point in my life, after years of faith deconstruction and religious instability, Julian’s Godhead was a welcome thunderstorm in my parched spiritual landscape.

Annabelle Clawson is an academic editor, feminist historian, and freelance writer, and a graduate from the University of Cambridge and Brigham Young University.

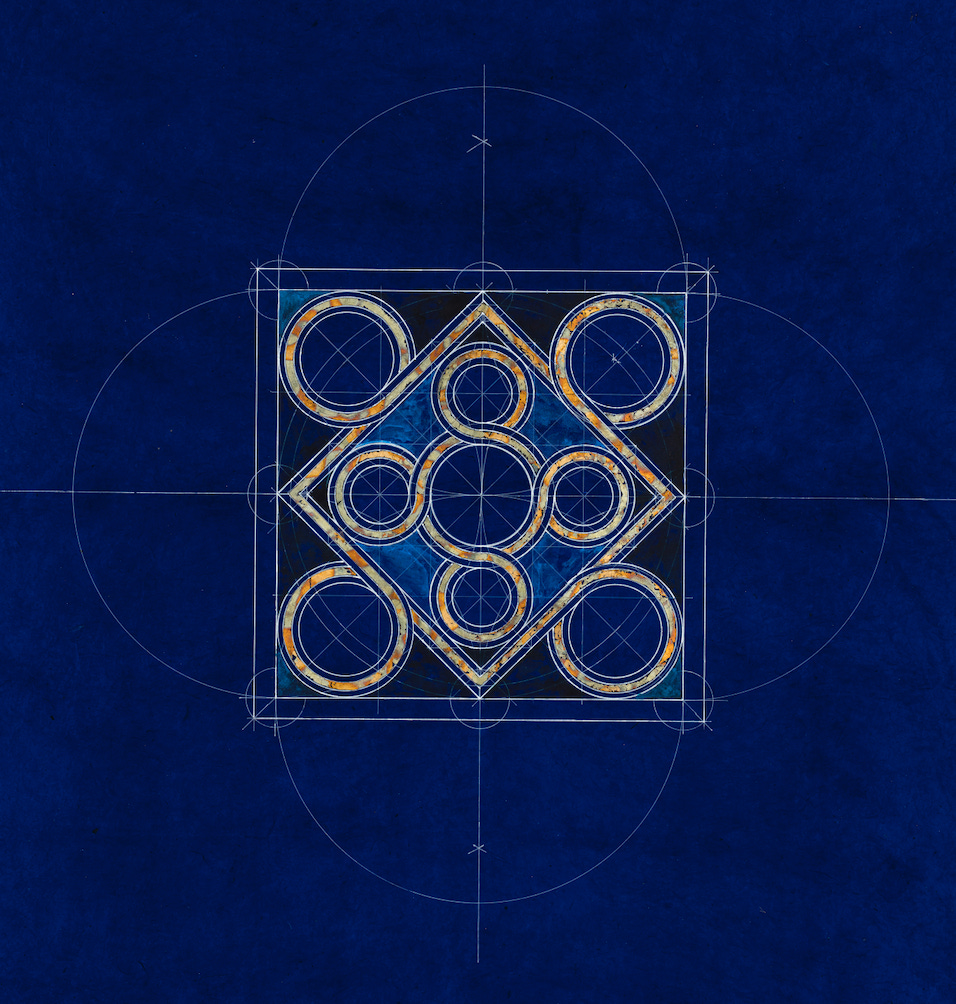

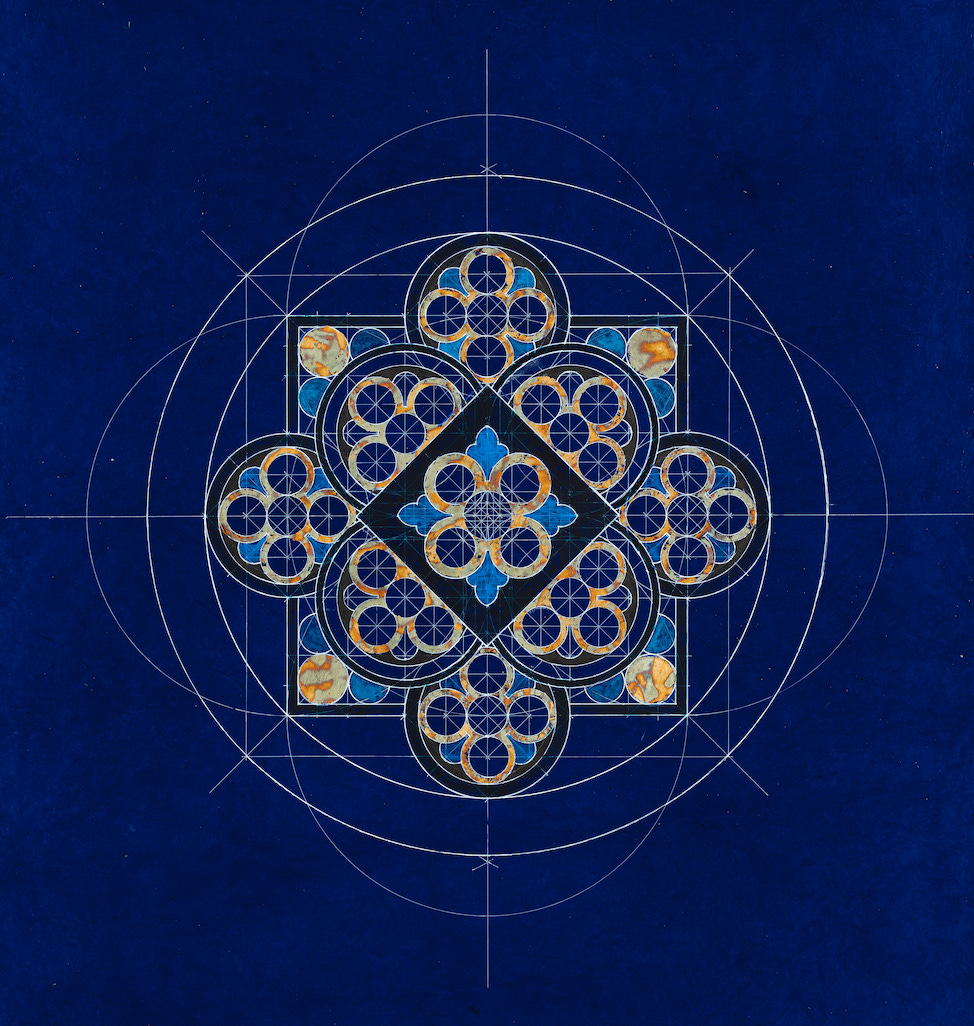

Art by Lisa DeLong.

You are channeling Julian through your words. I feel redeemed by these truths. Thank you❤️🩹