In the Book of Mormon, Latter-day gentiles are often condemned for “lyings,” one of the many scriptural terms that begs for more definition. I have come to suspect that these scriptural references to lyings are not necessarily referring to private dishonesty, like when a kid falsely claims to have completed their homework. Rather, I wonder if the problem of dishonesty being described in scripture is systemic in nature, created by political, ideological and other systems that reward partisan thinking.

The partisan mindset is destructive to well-intentioned faith, because it asks the wrong questions. Instead of asking what is true, and then seeking to do the difficult work of aligning one’s perceptions with reality, the partisan is only interested in a particular narrative of reality, one that advances his team’s objectives. He sees pursuit of truth as secondary to team loyalty. The partisan mind lives for the dopamine rush of seeing one’s team win, seeing the other team get “owned,” and comes to see all information as ammunition: ammunition that he can fire at the enemy, or that is headed his way from the enemy. The partisan cannot speak kindly of his opponents, because that might lead others to see the opponent’s humanity instead of their sins.

The partisan forms an identity out of his opposition to the other team: if the other team were to disappear, he would actually miss them because it is from them that he derives so much of his life force. Partisan thinking says that our identity and our righteousness are not gifts from God; they are constructs that derive their validity from another group being worthless (or at least worth less) and wrong.

As a faith community, our partisan thinking leads us to cut corners. Focused on team cohesion over real conversion, we can see covenants as “team jerseys,” and push loved ones to make commitments that don’t correspond at all to their actual level of conversion to the gospel. Jesus spoke of floods and winds that cause our spiritual unmooring, and even among the converted, floods of accusation and winds of ideology can be devastating to our peace in the gospel. When roots of conviction are shallow, we are prone to being swept away and, as Jesus further explained, the gates of hell stand ready to receive us. Hell, with all of its inner turmoil, is at once a state of mind in mortality and also an eternal destination for souls who have come to identify with its emotional baseline of chaos and conflict.

In restoration scripture we are told of the telestial world that “These are they who are thrust down to hell.” And further along we are given a stunning insight:

For these are they who are of Paul, and of Apollos, and of Cephas.

These are they who say they are some of one and some of another—some of Christ and some of John, and some of Moses, and some of Elias, and some of Esaias, and some of Isaiah, and some of Enoch;

In other words, hell is a collection of factions, a great bastion of partisan thinking. In the next verse we are given the stark telestial consequences of the partisan mindset: they cannot receive “…the gospel, neither the testimony of Jesus, neither the prophets, neither the everlasting covenant.” Why not? we might ask. I suggest that when we acquire a taste for factionalism and partisan conflict, over time we lose our appetite for the things that God offers us. We become unreachable by anyone – even God – who operates outside of our partisan framing.

As a means for undermining God’s influence in the world, the partisan mindset may be unparalleled because it provides a comforting false sense of the depth and strength of our roots. If I go to church because it’s what my team does, and I serve in the church because it’s what my team does, and I make covenants because it’s what my team does, my esprit de corps—my zeal for my team—can mask a lack of any real transformational personal experience of God. And I might not even stretch my soul for that vertical experience of the divine because I am satiated on a constant horizontal sugar high of team belonging.

The partisan mindset is sometimes developed in the context of our church activity, but often it is imported into the church from our politics. There are few things sadder than seeing Latter-day Saint politicians get lambasted by other Latter-day Saints for reaching across the partisan aisle, or for casting a lonely vote of conscience. And it is not surprising that many Latter-day Saint political partisans have taken the partisan accusing spirit to social media to lambaste church leaders over various stances, and without a hint of irony remind them what team they should be playing for.

Political partisanship can serve an important purpose, to be sure, as ideological partisans can temper each other’s excesses and hold each other accountable. But it too easily curdles into a mutual loathing and a disregard for basic honesty, mental and spiritual patterns that inevitably get applied in other areas of life.

There is no avoiding the reality that clarity can be divisive, but partisan thinking can only ever offer a false and lazy pretense of clarity. The antidote to partisan thinking is courage. It’s the courage to ask vulnerable questions when we face opposing views: Is there a truth this person is trying to speak to, but missing the mark in some way? Can I honor the hard truth that they are trying to address, and speak to it while providing a new angle, new insights that they might not be seeing?

Elder Neal A. Maxwell was very pointed in his descriptions of the church’s detractors. But even so, he counseled firmly against combative partisan responses:

…brothers and sisters, quiet goodness must persevere, even when, as prophesied, a few actually rage in their anger against that which is good. Likewise, the arrogance of critics must be met by the meekness and articulateness of believers.

Elder Maxwell’s counsel suggests that Christian discipleship is the position of confidence: confidence that a combination of meekness and articulateness will never fail to achieve God’s purposes, regardless of how people respond to those approaches.

In a recent seminar for mission presidents, President Dallin H. Oaks offered remarks to short-circuit our tendency to adopt a partisan mindset in our missionary service. The church newsroom summarized his remarks, with an important insight:

Latter-day Saints often refer to the Church as the only true church. Sometimes it might be done in a way that gives offense to people who belong to other churches or subscribe to other philosophies — ways that might imply arrogance, a “holier than thou” attitude, a monopoly on truth that excludes other faiths and philosophies, or suggestions that Latter-day Saints are better than others.

“We should try to avoid all of those ideas because none of them is true,” President Oaks said. “God has not taught us anything that should cause us to feel arrogant or superior to other people.”

President Oaks’ call for humility is the Christian position: self-checking, aware of limits, and committed to clear truths that lie outside of ourselves and our partisan teams. The opposite mindset – triumphalist partisan thinking – tends to mask insecurity and a lack of confidence: confidence that our doctrines are true, and that God can validate them to people who are sincere and seeking with real intent. President Oaks’ caution against arrogance and overclaiming are a call to rise to a discipleship that does not feel threatened by acknowledging the light and goodness in other belief systems.

The choice between partisan thinking or Christian discipleship is becoming ever more stark, and the spiritual well-being of Latter-day Saints increasingly depends upon our ability to choose what Isaiah referred to as “the waters of Shiloah that go softly,” or God’s gentle influence that, unlike partisan loyalty, never demands hatred for others or a selective view of reality.

Dan Ellsworth is a Latter-day Saint writer and host of YouTube channel Latter-day Presentations.

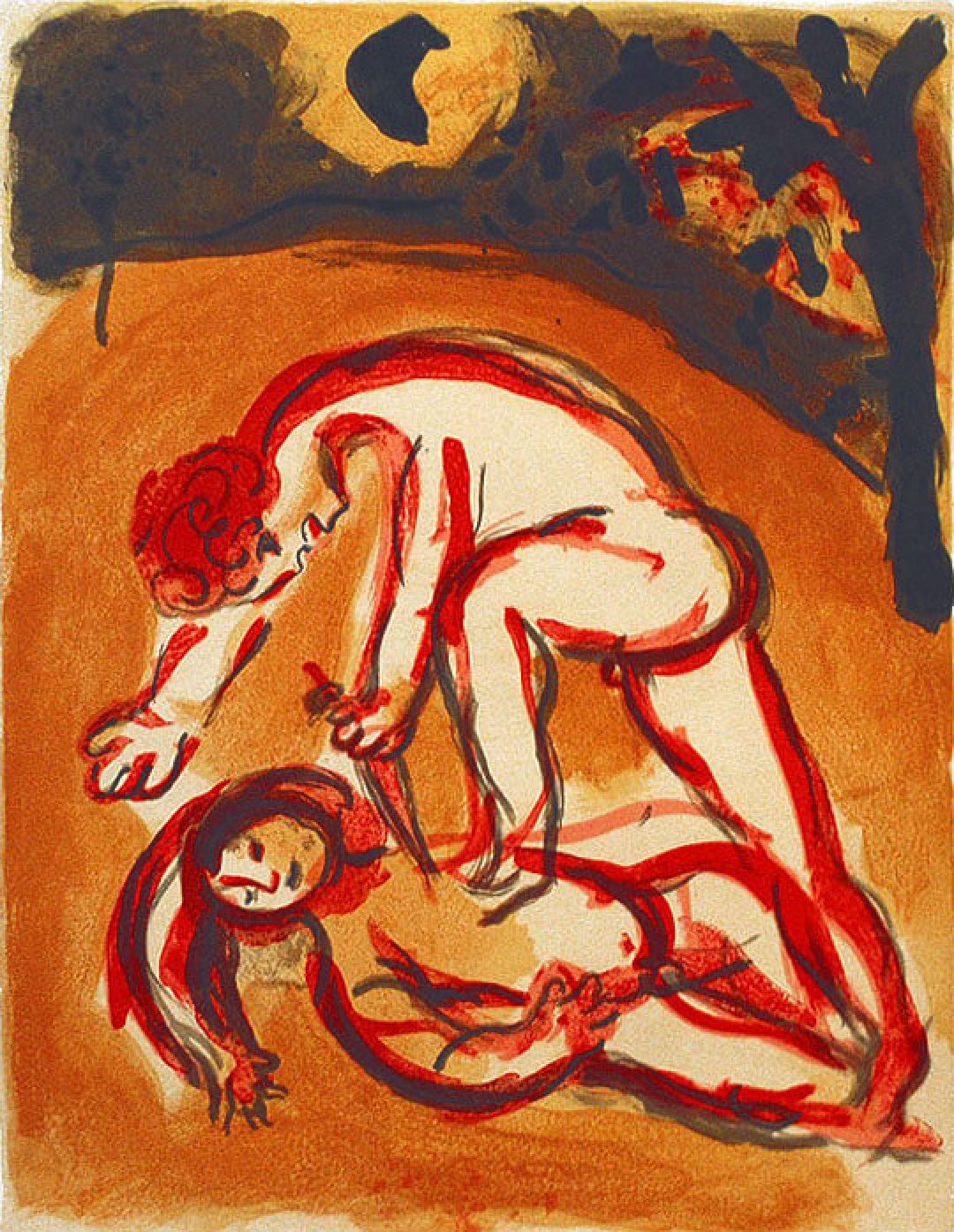

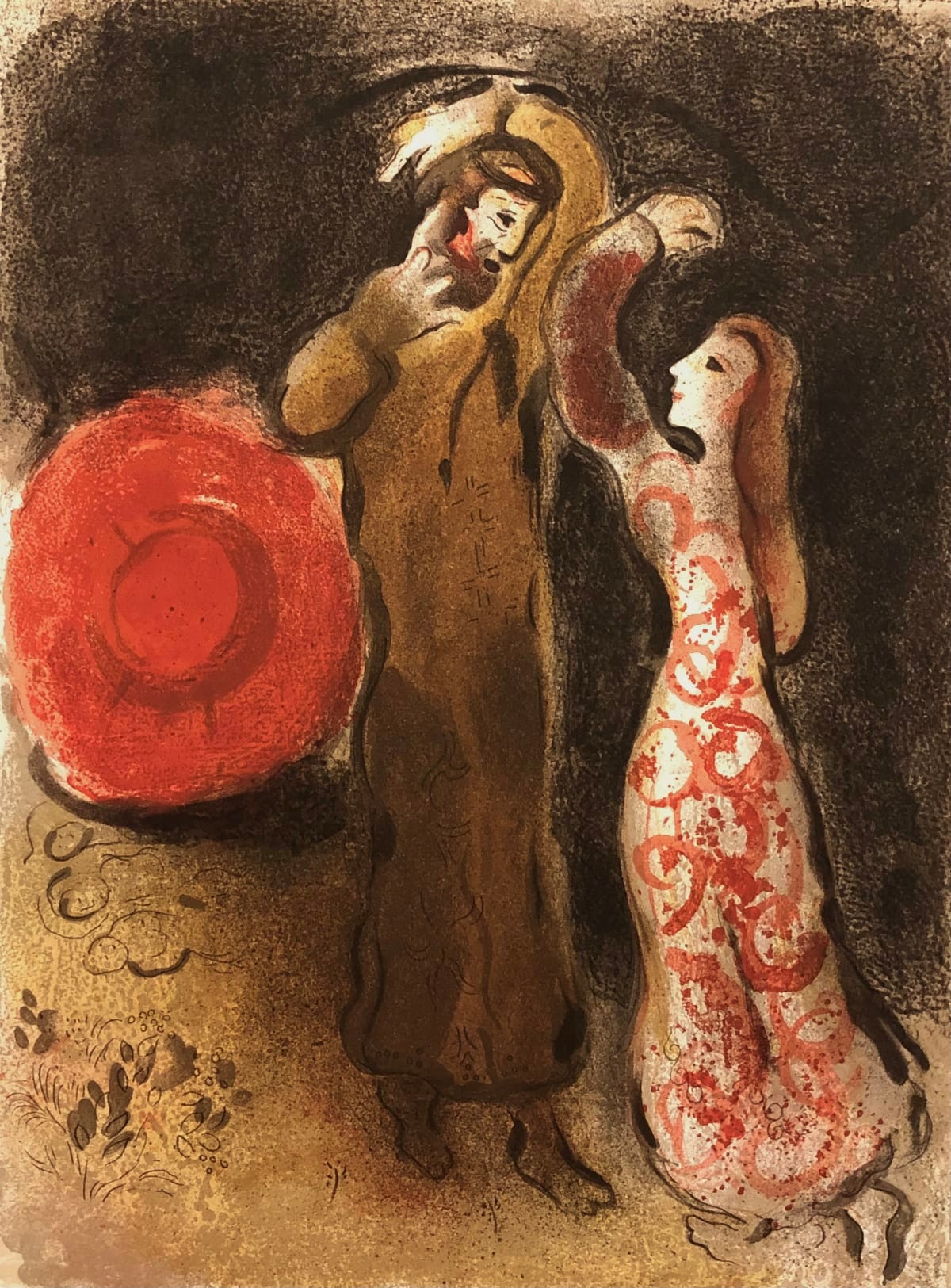

Artwork by Marc Chagall