Gerard Manley Hopkins was a Jesuit priest and perhaps the greatest of the Victorian poets. He suffered terribly from recurrent bouts of religious doubt and profound depression. In one of his “sonnets of desolation" we read a startling metaphor for spiritual struggle:

Not, I'll not, carrion comfort, Despair, not feast on thee; Not untwist—slack they may be—these last strands of man In me ór, most weary, cry I can no more. I can; Can something, hope, wish day come, not choose not to be.

It took a harrowing image—carrion serving as comfort food—to shock Hopkins out of his diet of disappointment.

In 1913, the Irishman Sir Hugh Lane proposed establishing a permanent modern art gallery in Dublin. He had secured pledges of funding to house and enlarge his own collection featuring such contemporary greats as Corot, Manet, Monet, Degas, and Renoir. The location was to be a middle-class Irish neighborhood—who could object to such an aspiration? Well, lots of people, actually. The country was on the brink of civil war; a citizen labor army of 20,000 had just armed themselves against violent police crackdowns; Dublin slums were pervasive and death rates high; the trauma of the Great Hunger was still a vivid memory among the aged; and the Great War loomed ahead, only months away. Dispensing even private funds—let alone public monies—for fine art in desperate times struck some as a tone-deaf indulgence. To others (like William Butler Yeats), affirming the enduring and the beautiful amidst hunger and squalor was an act of defiance against human fragility and contingency. (Aren’t the poor always with us?) In spite of Yeats’ impassioned support, Lane’s proposal failed to obtain public approval, and Yeats wrote a poem of bitter consolation to his ally in the effort, Lady Gregory. Hopkins’ wrestle was spiritual and cosmic; Yeats’ was political and moral. But in both cases, grievance threatened to canker their soul, and both rebuffed the temptation.

Yeats’ magnificent poem, “To a friend whose work has come to nothing,” ends with a call that challenges the human spirit to one of the hardest tasks it can ever face:

. . . Bred to a harder thing Than Triumph, turn away And like a laughing string Whereon mad fingers play Amid a place of stone, Be secret and exult, Because of all things known That is most difficult.

According to Paul Ricoeur, love means “unconditioned solidarity with and affirmation of the other.”1 For Dietrich von Hildebrand, love is “the affirmation of the being” of the other.2 For Martin Luther King, “love affirms the other unconditionally.” We could add endlessly to the list. In love we affirm the other—that is, we recognize the claims of the other person, that she is an end and not an object, she is the “Thou” in the I-Thou relationship3, the “I”-view of the other into which one must enter imaginatively and feelingly.4

The quiet heroism of Yeats’ poem is in its recognition that in so many of life’s transactions, we will not be affirmed. What then? Unrequited romantic love is the great fabric upon which poets embroider their tragedies. The desiccated desert of a loveless childhood, Romanian orphanages taught us,5 creates real-life shrunken souls that our most effusive compensations can seldom repair. Life in a close community wreaks its own wounds of neglect and disregard and slight. Our cultural moment has sensitized us to a plurality of individuals who feel insufficiently affirmed in their diverse identities. All the marginalized were the focus of Christ’s ministry and should be of ours.

There is, however, another deficit of affirmation that Yeats is addressing in his poem. Less morally urgent perhaps, less dramatic, but a hurt that spares no one and can nonetheless corrode the soul like a spiritual rust. It is the experience of disappointment—of seeing our projects or our plans, or our vision of a larger good, frustrated.

Human nature being what it is, in the absence of affirmation we just seek another kind of affirmation. Assurance that we are right in feeling aggrieved. Solidarity in our disappointment, frustration, sense of being wronged. We cultivate our own microbubbles of discontent.

“Be secret,” urges Yeats. “Be secret.” There is a time to make our protests long and loud. But there are also times to bear one’s grievance in private. When Job declared, “my heart shall not reproach me as long as I live” (27:6), he was making a pledge about a life in the absence of affirmation.

“And exult,” added Yeats. Exulting is usually a counterpart of success. Yeats makes it a companion of failure, of disappointment. How so? He gives us no drawn-out ballad about the heroism of tragic failure, or the pride of having done the right thing in a world gone wrong. Yet this capacity for which no name exists—the capacity to “be secret and exult”—seems necessary in the disciple’s spiritual repertoire.

Sometimes true discipleship is the courage to say hard things, to speak truth to power, and to put one’s reputation and life on the line. Sometimes, as we are implored in scripture ancient and modern, discipleship is the discipline to “stand still,”(Ps. 46:10), to “be still” (D&C 123:17). That may be a call to cease frenetic motion of mind and body and listen. And sometimes, it is a simple call to silence.

Hopkins silenced the interior demons of despair. As a Jesuit, he understood that nourishing despair is a failure of belief in Christ, not in ourselves. Silence in those circumstances is the allowing of space for Christ to enter into our interior dialogue, bringing hope.

Yeats silenced the inclination to spread disappointment like a canker. The “most difficult” thing is to know when to be quietly glad that some failures cause us grief—while we wait for renewed opportunities.

Terryl Givens is Senior Research Fellow at the Maxwell Institute and author and coauthor of many books, including Wrestling the Angel, The God Who Weeps, and All Things New.

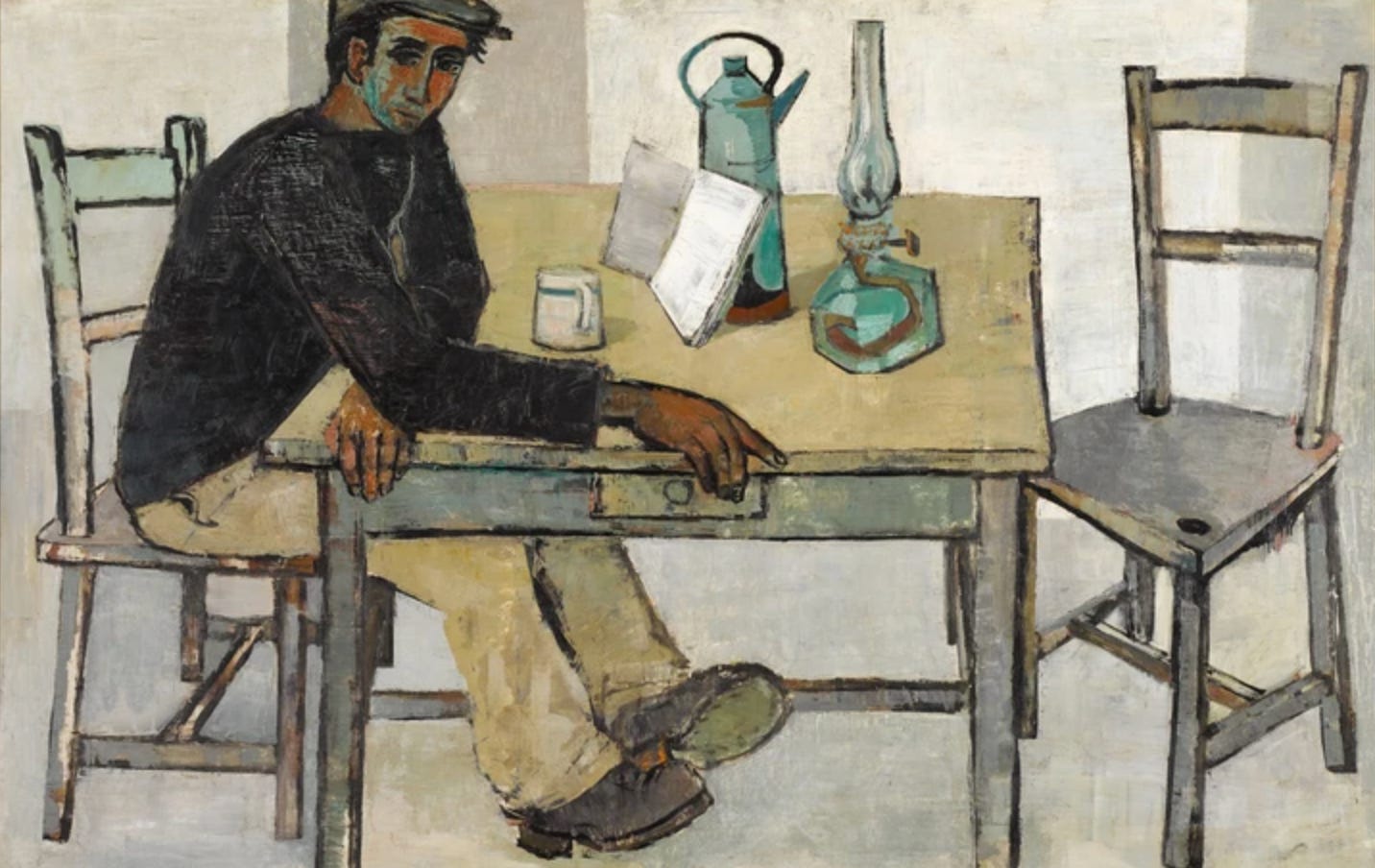

Art by Gerard Dillon.

Audio produced by BYUradio.

Cardinal Walter Kasper, Mercy: The Essence of the Gospel and the Key to Christian Life (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2014).

Dietrich von Hildebrand, The Art of Living (New York: Hildebrand Project, 2017), 37.

Martin Buber, I and Thou, trans. Ronald Gregor Smith (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1958).

José Ortega y Gasset, Man and People, trans. Willard R. Trask (New York: W. W. Norton, 1957).

For those too young to remember, in 1990, the outside world discovered Romania’s network of “child gulags,” in which an estimated 170,000 abandoned infants, children, and teens were being raised. The damage done by systematic neglect was in most cases irremediable. See this article.

Beautiful

Thank you