Our Distant Ancestor

Several years ago, while on vacation in Israel, I went to Mount Carmel, the traditional location for the epic showdown between Elijah and the priests of Baal recorded in the Old Testament. Prior to the visit, I reread 1 Kings 19. The story ends with a detail I had not remembered. After the people recognize that Elijah’s God works the miracle and Baal does not, Elijah says to the people, “Take the prophets of Baal; let not one of them escape. And they took them: and Elijah brought them down to the brook Kishon, and slew them there” (1 Kings 19:40). At the Christian monastery at Mount Carmel, a statue of Elijah stands over the subdued body of one of the priests, wielding a knife in his right hand.

Elijah, the murderer?

I am not alone in finding aspects of the Old Testament disturbing. When I was knocking doors in Hokkaido, Japan as an evangelizing missionary, I met a man who told me he believed in the God of the New Testament, who was compassionate and loving, but not in the God of the Old Testament, who was vengeful and violent. It was the first time I encountered an explicit version of a nearly 2000-year-old idea: Marcionism. The scriptural canon of Marcion of Sinope included only a gospel similar to the gospel of Luke and some Pauline letters; the Hebrew scriptures were rejected. The early Christian church in Rome excommunicated Marcion and declared his teachings heresy in 144 A.D., but that has not stopped his ideas from reappearing in a variety of forms. I’ve heard fellow believers reject or deemphasize the Old Testament many times. Why do Marcion’s ideas keep resonating and reappearing—including once from the man I met in Hokkaido—thousands of years after his official excommunication?

Marcion’s ideas are appealing because it is not easy to read or justify episodes of the Old Testament that depict intolerance, violence, or other morally foreign ideas. However, ultimately, the Marcionite rejection of the Old Testament must itself be rejected. We can reflect on the reasons Old Testament episodes feel uncomfortable while still acknowledging the Old Testament as an important part of our heritage.

The legal rules outlined in the Torah reflect the culture and values of the ancient Israelites. Freedom of speech and religious liberty are foundational to modern democracies, but these rights are antithetical to the ancient biblical law of Moses that prescribed stoning for blasphemy and death for false prophecy (see Leviticus 24:16 and Deuteronomy 18:20, respectively).

Modern Christians looking to distance themselves from Old Testament values already have conveniently on hand the New Testament, where Jesus himself de-emphasizes the law of Moses. Jesus explains that what “was said by them of old time” is transcended by what He says. He draws a distinction between the “weightier matters of the law”—mercy, faith, and justice—and the legalistic details that preoccupied the religious leaders of His day (Matthew 23:23). The rejection of the old law is made more explicit after Jesus’ death. In the Acts of the Apostles, Peter dreams of a divine voice telling him to kill and eat animals considered unclean under the law of Moses. Helped by the miraculously-timed visit of the Gentile Cornelius, Peter understands the dream to mean that God shows no favoritism to the people of Israel and that he must stop observing parts of the law of Moses. Paul is the most antagonistic towards the law of Moses of all the New Testament authors, disparaging what was “written and engraven on stones” by God on Mount Sinai as the “ministry of death” (2 Corinthians 3:7).

A story in the gospel of Luke illustrates the clash between New and Old Testament values and how Jesus invites his disciples to adopt more tolerant attitudes toward differences in belief than some of the Old Testament protagonists had. Two apostles, James and John, ask Jesus whether they should burn down a city that did not receive them: “Lord, do you want us to command fire to come down from heaven and consume them, just as Elijah did?” Jesus not only declines the offer, but rebukes James and John. He tells them, “the Son of man is not come to destroy men’s lives, but to save them” (Luke 9:56). For years, my reaction to this story was to chuckle, astonished by the apostles’ thirst for vengeance. But I’ve since come to view their question more charitably. From their perspective, James and John were faithfully asking for a miracle analogous to what Elijah experienced when he combusted soldiers that came to arrest him (see 2 Kings 1). The disciples were likely just as shocked by Jesus’ response as modern readers are by their question.

Despite the ways in which Jesus and the New Testament offer correctives to the Old Testament, Christian readers cannot discard the Old Testament altogether. Its images, stories, metaphors, and prophecies are too entangled with later revelations. Martin Luther described the Old Testament as “the swaddling cloths and the manger in which Christ lies” because Christian theology, tradition, and scripture all grew out of the Hebrew scriptures. Because Jesus and the New Testament authors are constantly citing and invoking the Old Testament, Marcion’s rejection of the Old Testament suggests the rejection of all Christian scripture. The Gospel of John opens by borrowing language (“in the beginning”) and images (“light” / “darkness”) from the creation story in Genesis. In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus reads from the Isaiah scroll in a synagogue and then announces, “This day is this scripture fulfilled in your ears” to announce his mission (Luke 4:21).

Many of Jesus’ parables have deep Old Testament roots. For example, the story of the prodigal son has striking parallels in plot and language with the story of Jacob and Esau’s reconciliation in Genesis. Shared elements of the two stories include the following: 1) The initial cause of the familial rift is an inappropriate taking of inheritance; 2) the estrangement involves physical distance; 3) the estrangement lasts for several years; 4) the estranged family member contemplates reconciliation but is fearful of the other party’s potential response; 5) the two parties reunite, with running, kissing, and falling upon the neck specifically mentioned; and 6) gifts accompany the reconciliation. The parable of the vineyard in Matthew likewise echoes the setting and themes of Isaiah’s song of the vineyard (see Matthew 23:33–44 and Isaiah 5:1–10).

Furthermore, some of the statements we most strongly associate with Jesus are, in fact, direct quotations of the Old Testament: “fishers of men” comes from Jeremiah; “My God, My God, why hast thou forsaken me?” comes from the Psalms; and “Love the Lord with all your heart, might, mind, and strength” comes from Deuteronomy. Once you start looking for echoes of the Old Testament in the New Testament, you start to see them everywhere.

So we cannot separate the God of the Old Testament from the God of the New Testament, as Marcion suggested; the Old Testament is too embedded in Christianity’s heritage. For modern Christians, the Old Testament is like a distant ancestor who lived in a time so strange it’s sometimes impossible to understand his worldview. He said some things that make us cringe and some things that inspire us. But no matter how we feel about him, we wouldn’t be here without him.

Another reason to reject Marcionite interpretation (such as that the God of the Old Testament only cares about a select few while the God of the New Testament teaches care for all, especially the downtrodden) is that it relies on a caricature of both halves of the Bible. The New Testament has plenty of its own thorny episodes. While at times Jesus does nudge his disciples towards greater tolerance (as in the episode above with James and John), there are also times when he insinuates that non-Israelites are lesser. For example, Jesus originally dismisses a Canaanite woman pleading for a healing, telling her, “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.” After she again asks for help, Jesus says, “It is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs,” implying that the Israelites are children at his table while the Canaanites are dogs (Matthew 15: 24, 26). I wouldn’t consider that a model of tolerance.

The New Testament also contains passages that are difficult for modern readers to justify. The epistles teach that women should not speak in church and should be submissive to their husbands (1 Corinthians 14:34–35, Ephesians 5:24) and the rhetoric of the New Testament authors can sometimes approach antisemitism (see, for example, 1 Thessalonians 2:14–16).

Perhaps the merit of reading scripture is not just the opportunity to embrace ancient and eternal truth but also to prompt reflection and appreciation through exposure to different contexts and moral systems. The Book of Mormon invites its readers to reflect and “learn to be more wise than [ancient peoples] have been” (Mormon 9:31).

The Marcionite interpretation also suggests that the Old Testament is more simplistically harsh and uncaring than it really is. Starting in the Book of Genesis, we do read a story that focuses on a family line that appears to receive God’s preferential treatment. However, the Old Testament also prompts us to have sympathy for the downtrodden and those not chosen to be part of the covenantal line. The great moments of pathos in Genesis come from these unchosen characters. Hagar was Abraham’s slave-turned-second-wife who was evicted with her son due to tension between her and Abraham’s first wife and between their sons. Abandoned in the desert and running low on supplies, Hagar prays, “Let me not see the death of the child” (Genesis 21:16). At that point, the angel of God intervenes, shows her a nearby well, and provides a hopeful promise about her son’s future. A generation later, there is more sibling rivalry between Isaac and Rebekah’s twin sons, Jacob and Esau. Taking advantage of her husband’s blindness, Rebekah tricks Isaac into giving Jacob the birthright blessing instead of Esau as Isaac had intended. When the plot is complete and revealed, a despairing Esau cries, “Have you but one blessing, my father?” (Genesis 27:38). The authors of the Old Testament books prompt the readers to sympathize with the unchosen and know that they are not abandoned by God.

The God of the Old Testament can be loving and caring, even for the downtrodden and the unchosen. Even though the law of Moses frequently invokes the death penalty for actions that wouldn’t even be considered crimes today (as previously mentioned, false prophecy was punishable by death), it also contains the merciful commands to “love your neighbor” and to “love the foreigner as yourself” (see Leviticus 19:18, 19:34). As I was reading the Old Testament a few years ago, I was startled to learn that, according to the Book of Amos, the Exodus story of the children of Israel is not exceptional and that God leads other peoples just as he does the Israelites:

Are ye not as children of the Ethiopians unto me, O children of Israel? saith the Lord. Have not I brought up Israel out of the land of Egypt? and the Philistines from Caphtor, and the Syrians from Kir? (Amos 9:7).

So, the Philistines—Israel’s enemy, the tribe Goliath belonged to—were guided out of Caphtor by God and experienced their own Exodus! The Old Testament teaches that God cares for all, including the ancient Israelites’ military enemies.

There is a through line that connects the ideas of the Old Testament with those of the New Testament and even with modern values about each individual’s worth. In his book, Dominion, Tom Holland argues that the modern concept of “human rights” and the legal movement to ensure “equal justice to every individual, regardless of rank, or wealth, or lineage” grew out of the biblical command to “love your neighbor.” Of course, there are real differences between the values of the Old Testament and between the values of later scriptures (not to mention our own modern values), but they should be understood in the context that much is shared and inherited from the Old Testament.

Is there a satisfying way to reconcile this clash of values between the Old Testament and other books of scripture? One approach is to think of laws in the Old Testament as the first steps in a spiritual evolution culminating in a later, higher law. Society has made important moral progress in the past few thousand years. The Law of Moses was intolerant and severely restricted an individual’s liberty, but that was not unusual by ancient standards. Tom Holland remarks that the more he studied the ancient Greeks and Romans, the more “alien” he found their values:

The moral values of Leonidas, whose people had practised a peculiarly murderous form of eugenics . . . were nothing I recognised as my own; nor were those of Caesar, who was reported to have killed a million Gauls, and enslaved a million more. It was not just the extremes of callousness that unsettled me, but the complete lack of any sense that the poor or weak might have the slightest intrinsic value.

Those who step into the distant past encounter a world where human life and liberty were far less valued. Slavery and infanticide were widespread; the concept of “human rights” was still in embryo. It took plenty of trial and error for societies to learn these lessons and to eventually embrace individual rights and abolish slavery and infanticide. Perhaps the law of Moses was a necessary stepping stone in that progression.

However, this narrative on human progress can go against the grain of (sometimes naive) restorationist belief. Restorationist rhetoric emphasizes how the restored gospel remains unchanged from the gospel revealed to ancient prophets in all dispensations. The restorationist narrative of scriptural history focuses on cycles of apostasy and restoration but often overlooks crucial human progress that has been made since the birth of Christ. Sometimes the story of restoration mistakenly feels like a restoration ex nihilo in which the Church and the gospel were brought back in an unchanged and perfect state after a long pause, untouched by the context of the restorers. Reading the Old Testament offers a healthy antidote to such an interpretation: The moral foreignness of some scripture reminds us that our understanding of truth and goodness has changed dramatically since the era before Christ—and often for the better.

Is there a way to justify the Old Testament’s more disturbing, violent episodes? The Baptist theologian Roger E. Olson wrote a helpful overview of possible strategies in a blogpost titled “Every Known Theistic Approach to Old Testament ‘Texts of Terror.’” Growing up, I heard and read the “literal interpretation,” also sometimes called the “divine command” theory, which accepts divinely commanded Old Testament violence at face value. However, the divine command theory does not explain why God’s actions and attitudes seem to change between different books of scripture. The divine command theory does not explain why Jesus rebuked James and John for their suggesting that he burn a city that did not receive Him, whereas Elijah had a free reign to use God’s power to combust hostile soldiers and Joshua was commanded by God to destroy “all that breathed” in the promised land (2 Kings 1:12, Joshua 10:40). Divine command theory also raises difficult questions about the nature of God and goodness. If God can command actions that are not good, then God is not the good God that we all have imagined. If God’s commands to kill “all that breathe” in the Book of Joshua are, in fact, good, then what does “good” even mean? I prefer to think of the egregious violence carried out by God’s chosen people in the Old Testament as not divinely mandated but only expressed that way by biblical authors. Perhaps scriptural authors misled readers to rationalize violence or perhaps they had been misled themselves. I recognize that rejecting the apparent meaning of scripture in favor of one’s personal interpretation is a slippery slope; once you start, where do you stop? There is no easy solution to violence in the Old Testament, and I certainly don’t have the answers. Instead, I believe we are called to observe and reflect on the tension we see.

Some may find it awkward and difficult to admit that canonized scripture contains values at odds with what we ourselves hold. One strategy is to ignore this tension and deny any clash of values. For example, we can hold to a sanitized version of the Old Testament, completely consistent with the values of a modern gospel. This is the approach of many sermons, Sunday School manuals, and Children’s Bibles: Draw out the anecdotes and ideas that are spiritually enriching or easily applicable today and ignore the more difficult and shocking episodes.

A similar approach that also refuses to acknowledge any tension between modern beliefs and scripture is to pretend that we are completely comfortable with the values of the Old Testament. This is what the Puritans of seventeenth-century Massachusetts tried. They sought a pure, uncorrupted Christianity straight from the Bible and proclaimed that “no custom or prescription shall ever prevail amongst us . . . that can be proved to be morally sinful by the word of God.” They included citations to the law of Moses in their legal code, so we know they were not naive about what they were signing themselves up for. In the Massachusetts Body of Liberties of 1641, adultery, witchcraft, homosexual intercourse, stealing, and bearing false witness were all capital offenses.

However, other elements of their laws reflect a tradition of liberty developed enough that even the Puritans felt uncomfortable jettisoning it. The same body of laws also outlines a democratically-elected government, redress for victims of domestic abuse, and the right to a trial and to appeal—none of which are found in the Bible. Eventually, the Puritans fell short of their stated goal of complete fidelity to scripture and settled for banishing heretics and branding adulterers instead of killing them. For the Puritans, a simplistic embrace of the Old Testament led to such harsh treatment of criminals that even their watered-down punishments are remembered by society as cruel and intolerant.

We are better off frankly acknowledging the tensions we feel with the Old Testament. First, acknowledging our discomfort helps us understand our own culture and vantage point better. Second, this approach helps us appreciate the mixed moral traditions we inherit from many sources. We all expect that blasphemy against God, church, and king would not be punished with death; not true for those who live only under the law of Moses. Third, internalizing that we hold non-scriptural values helps us recognize that we have more in common than we may have thought with those who do not share our faith, including with those who do not belong to any religion. Thus, articulating and reflecting on how and why certain Old Testament episodes feel uncomfortable can ultimately be spiritually uplifting.

Growing up, I was self-conscious, sometimes painfully so, about how different I was from my peers who did not belong to the same religion as me. A few years ago, I went backpacking in Big Sur with some friends, most of whom were not religious. As we hiked on the green hills overlooking the Pacific Ocean, the conversation turned to our differing beliefs. My friends’ response to my religion was a mix of consternation and admiration. We still have real and significant differences in values and how we view the world. Most of them do not see the value in reading scripture or accept a higher moral authority. Still, we also share many values; we all value community and open dialogue, including with those with whom we disagree. We all desire to live a good and happy life, to help the poor, and to resist technological and social currents that drive people away from each other. Were it possible to quantify the distance between different individuals’ sets of values and morals, which distance would be greater: the distance between my agnostic friends and me, or the distance between modern Christians and the ancient Israelites, both of whom consider themselves members of God’s covenant?

That the past is a foreign country is both a cliché and an understatement. In the age of the internet, the culture shock we experience from travelling across continents is dwarfed by the culture shock we experience when we open up the Old Testament. The Old Testament’s depictions of what God commands and condones clash with common modern conceptions of God. This poses difficult questions for those who believe God is the same yesterday, today, and forever. But to separate a vengeful God of the Old Testament from a loving God of the New Testament ignores both Testaments and their instructive entanglements. The Old Testament is our distant ancestor; it offers the first soil in which Christian belief took root and then spread worldwide. While the Old Testament’s intolerance and violence is indeed disturbing, we must not look away. Frankly acknowledging the tension between modern values and Old Testament values can lead us to reassess the remarkably accepting society in which we live and reaffirm our own commitment to individual liberty and religious pluralism.

Peter Wilson lives in Orange County, California with his wife and two young children.

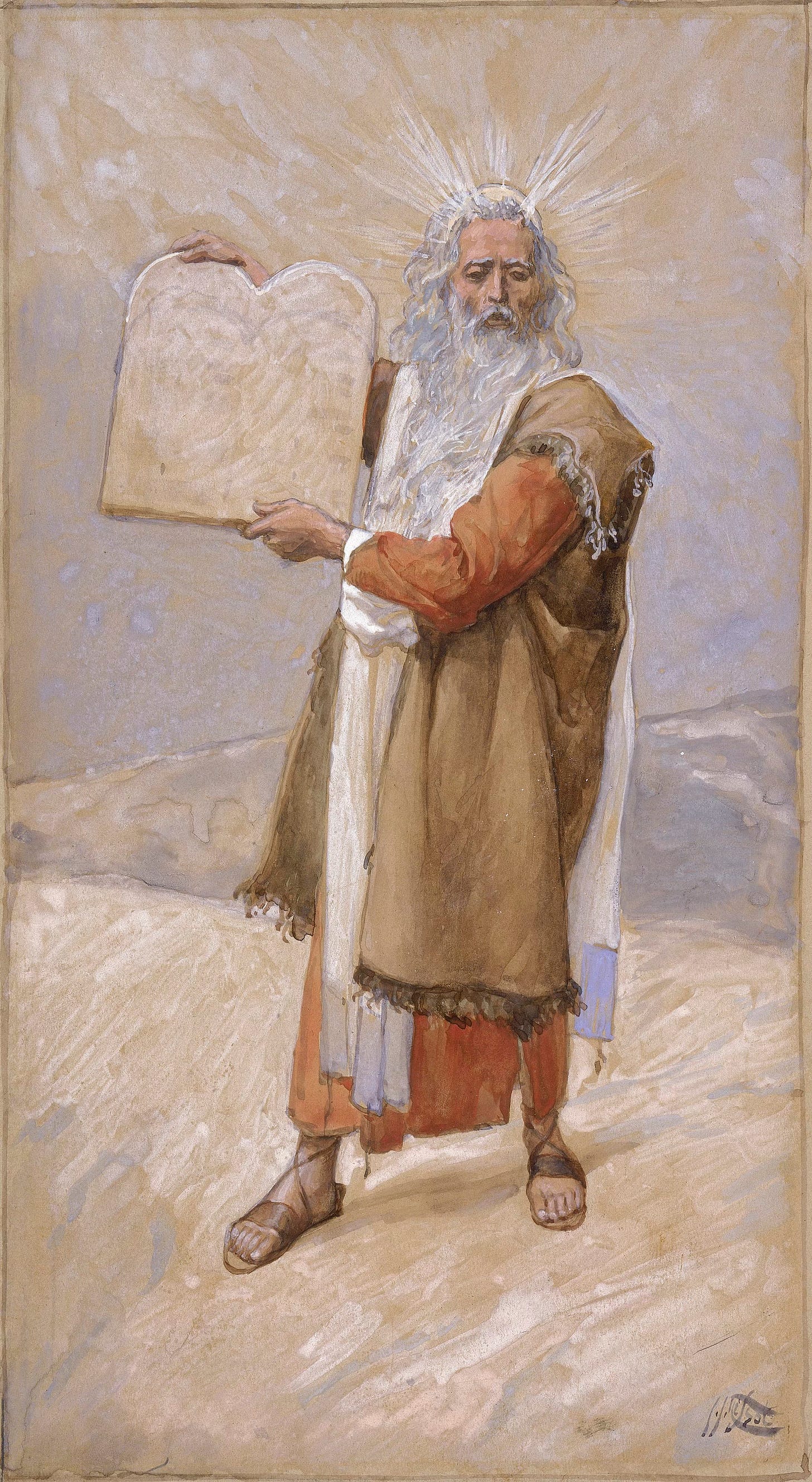

Art by James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836–1902).

I congratulate Peter Wilson on his thoughtful article. While I generally agree with him, I have the following observations:

1. With few exceptions, God kills, or at least permits the killing, of each of His children. Death is part of God's plan; we are not supposed to live forever. Usually we are taken one at a time, but sometimes God causes (or permits) entire populations to be taken at once. This happened, for example, at the time of the Flood when all of mankind had become corrupt, save only Noah and his family. The reason murder is a sin is not that death, in and of itself, is evil; it is that man arrogates to himself a perogative that belongs to God or to the state. I suspect that the primary reason modern Christians are bothered by Old Testament (and, to some extent, New Testament--see the story of Ananias and Sapphira in Acts 5) stories of God's vengeance is the involvement of God's people in the killing. For example, the story of the killing of the prophets of Baal in 1 Kings 18 would probably be less offensive to modern Christian sensibilities if God had simply sent down fire from heaven to consume the prophets, rather than commanding (or permitting) Elijah to do the job himself.

2. For humans to live together in a state of order, laws must exist, and enforcement mechanisms must be established, which must include, in extreme cases (such as war or the apprehension of dangerous criminals), the taking of human life. One of the hallmarks of the modern state is that it assumes a monopoly over the taking of human life. In cases where the state is weak, hopelessly corrupt, or non-existent, individuals may be left with no recourse but to enforce the laws themselves or to revolt. The Icelandic sagas provide a good example of a society where enforcement of the laws was left to individuals or clans. One approach to the story of Elijah and the prophets of Baal is to look at Elijah as a patriot revolting against the corrupt regime of Ahab and Jezebel.

3. Modern states can generally afford to maintain extensive prison systems, which make it possible to enforce laws primarily through the incarceration of criminals. Many ancient states couldn't afford that luxury, and so were forced to resort to other means--including the death penalty--to enforce their laws.

4. 2 Nephi 29:13 states that the Lord "shall also speak unto all nations of the earth and they shall write it." This suggests that every nation has some portion of the truth, which is reflected in its laws, customs, and beliefs. The Children of Israel during Old Testament times enjoyed significantly greater acess to the truth than did their neighbors, but the truth they enjoyed was less than the truth that was proclaimed by Jesus Christ during His earthly ministry. The restoration of the Gospel through the Prophet Joseph Smith brought additional light and knowledge to the Earth, and the ninth Article of Faith assures us that the Lord "will yet reveal many great and important things pertaining to the Kingdom of God." So all nations and religions at all times have some access to the truth, but that access (including our access as members of the "only true and living church" on earth) is limited and imperfect.

5. Political and moral views evolve over time. Just as my children are horrified by some of the political and moral views my grandparents held, my grandparents would be horrified by some of the political and moral views my children hold. Over the past 200 years or so, the general trend has been towards more tolerance and less moral responsibility. Who is right? All of us are wrong, of course, to one degree or another. If and when we get it right, and our social and political institutions conform to ultimate divine standards, we will be translated. In the meantime, it would behoove us all to look at the attitudes and behavior of our ancestors, including our spiritual ancestors whose record is reflected in the Old Testament, with humility and sympathy, and with the hope that our descendants will look at our attitudes and behavior with the same spirit.

Randy Muhlestein

South Pasadena, California