Ordinary Evil, Extraordinary Responsibility

Reflections from Auschwitz

“We are the hollow men / We are the stuffed men / Leaning together / Headpiece filled with straw. Alas!”

—T.S. Elliot

A year ago at Hebrew College, a rabbi addressed a group of BYU students and, with surprising and vulnerable candor, recounted how members of my own community, the Latter-day Saints, performed posthumous proxy baptisms for Holocaust victims in the 1990s and through the 2000s despite a 1995 agreement meant to end the practice. “This was an atrocious offense to me and my people,” he said somberly, noting that some of the Holocaust victims included members of his own family. It was an attempt to rewrite the religious identity of individuals who had died at the hands of regimes that sought to erase that very identity and therefore, a terrible violation of their memory.

I was among the students, simultaneously sorry and grateful, when he looked at us with that pain in his eyes and plainly told us that we had put it there. For lack of thought, members of my community hurt an entire people. I’ve come to realize that almost everyone, including myself, likes to believe they are open-minded and logical. But perhaps the greatest barrier to genuine thought is precisely that assumption, whereby we confuse the feeling of being thoughtful with the practice of thought. We quote, discuss, and perhaps critique but less often wade through the mire of our own premises and how they quietly sustain the world’s injustices.

Such was the case with my community. It was precisely this offense that led me to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum for a three-month internship, not to assuage a sense of misplaced guilt but to understand what it meant to take up responsibility for a history that wasn’t “mine,” yet one that called on me to do something. I wished to make amends. In doing so, I came to find that to truly think is to see and assume responsibility for the invisible meanings of the ideas and structures that we inherit and yet are often concealed by our comforts.

It took me a full month of living in Auschwitz to turn off the lights in my apartment without extensive mental preparation. The shadows appeared to me more malicious than usual, each sound more sinister. I never believed in the haunting of ghosts until I came to the museum, a moment at which I was promptly convinced of its inevitability. Being housed in the former SS officers’ apartments as an intern at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum provided a frightening welcome to my new work and life.

Yet in the light of day, the camp appeared almost the opposite of what I expected. Groups of visitors walked with tour guides, headphones on, their movements reminiscent of countless other European tourist destinations. Strangers greeted me warmly with dzień dobry! The sun felt nice on my skin, the grass appeared lush, and birds chirped their usual charming songs. It was disorienting, particularly because with enough eventless nights and pleasant days, I became accustomed to living at the museum. I was in a place whose history stands as a contender for the worst on earth, yet something about it felt suspiciously, disturbingly ordinary. It was slowly dawning on me that the real horror of Auschwitz was not only the enormity of suffering but the ordinariness of those who caused it and the ease with which any of us could, under certain conditions, participate in harm without fully realizing it.

On my first day, my supervisor met me by the guardhouse to give me an extended tour. She gestured to a wall just fifty meters away, explaining that behind it lay the house of Rudolf Höss, Auschwitz’s former commandant. “No one shows you that,” she said, “because people are interested in where people died, not the homes of the killers.” I observed visitors gather and linger at Höss’s gallows without a glance toward his home. The scenes of horror seemed to obscure the banality of the perpetrators’ lives.

The fact of evil that emerges from ordinary life is of deep concern. Tolstoy captured it in a single paradoxical line, “A life most simple and most ordinary and therefore most terrible.”1 He writes of a person whose life was spent preserving comfort and conventional morality for the sake of convention, unconscious of the hidden consequences this had on the people around him. In this sense, a life in which one’s social or authoritative superiors are the determinants for one’s thoughts or behaviors can in fact be both simple and terrible.

Nearly a century after Tolstoy, political theorist Hannah Arendt saw this, too, as she observed the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a high-ranking Nazi official who oversaw the logistics of mass deportations of Jews. Despite the enormity of his crimes, Eichmann presented himself during his trial in Jerusalem as an unremarkable bureaucrat, claiming he was simply “following orders” and fulfilling his duties within the Nazi regime. Arendt wrote, “The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, but terrifyingly normal.”2 Evil, she concluded, arises from the failure to think. It stems from people who do not wrestle with the implications of their beliefs and behaviors and simply follow the easiest, most comfortable path.

The postwar denazification tribunals reveal the “banality of evil,” as Arendt coined it, in statistical form. Of more than four million cases, ninety-five percent of Nazis were categorized, via a detailed questionnaire the Allies used to establish complicity, as “followers” or “persons exonerated,” revealing that a great many of them were not necessarily motivated by a deep hatred of Jews but by practicality. The tribunals were an enormous task, with four million denazification proceedings carried out between 1946 and 1949, quickly overwhelming the available resources. It is therefore important to note that critics of the process called it a “follower factory” that whitewashed subjects’ responsibility. Moreover, anti-semitism was and is very real and very dangerous, and acknowledging the ordinary motivations of many Nazis does not diminish that fact. In any case, the results of the tribunals stand to reveal a deeper truth. We can be confident that there are many whose motivations for Nazi participation are easily recognizable: to provide for their families, to thrive, and to feel comfortable.

Comfort, I realized at Auschwitz, is its own kind of sin—and we are all guilty of it. We procure “rational” frameworks that give us permission to enjoy the pleasures of our own individual worlds even when people around us are left wanting. In a figurative sense, there are walls everywhere. It could be the pretty shopping bag that contains my newly purchased clothes that may very well have been made by exploited workers, the shiny plastic neatly wrapped-around animal products whose source likely suffered. There are also walls, more literally, like those separating me from incarcerated or detained individuals, or the one separating Israel from Gaza. These walls, thoughtlessly and banally constructed or accepted, breed a sense of desensitization and dehumanization. These are the walls we build for ourselves, and, in the words of James Baldwin, “There are too many things we do not wish to know about ourselves.”3 Not the least of which is the reality that, in a world with such economic and social disparity, comfort, and privilege, “mere participation” in society means that in some way I am living off the labor of other people.

In the world of the Third Reich, where genocide had been bureaucratically organized and socially embedded within the Nazi state, many Nazis understood themselves as merely participating in society. Their actions were perhaps the best option for their families, sanctioned and rewarded as they were by the state. For a German physician in the 1940s, the quickest path to professional acclaim may have been through medical experiments at Auschwitz. Our twenty-first-century world should strike us as morally familiar. We ask, “How could they have let this happen?” The answer is simple: People benefit from serving that which is most profitable. The government rewards those who carry out its tasks, endlessly favoring loyalty over integrity. Corporations that put profit before environmental care contribute to pollution and resource depletion at the expense of the vulnerable. War sustains livelihoods within the military-industrial complex. And our politicians, so well-paid and comfortable, may find it easier to ignore their complicity. Even initiatives meant to address suffering are more frequently led by elites, estranged from the vulnerable that they claim to serve. Such realities should awaken us to the fact that comfort dulls our vision and encourages thoughtlessness. Are my comforts shielding me from seeing the world’s evil? Wealth or comfort, after all, in the words of Kevin Spinale, a Jesuit priest and professor, “ensures that the wealthy can live apart from ugliness: the ugliness of pollution, congestion, squalor or violence, as well as untreated physical and mental illness . . . that the vast majority of human beings daily endure.” It is little wonder that Jesus condemns wealth. Perhaps we always ought to be suspicious of our comforts, of our wealth. Comfort is not just a protection from evil; it is often its bedmate.

Eventually, I realized that the ordinariness I came to observe at the museum was significant. The absence of supernatural fear (the ghosts I’d imagined) was replaced by a more chilling realization: The problem with Nazis arose precisely from the fact that they were not supernatural. They were not monsters, demons, or aberrations of nature, but human beings exhibiting extensions of behaviors we all possess. To label them as anything else creates a dangerous distance between their actions and our own capacity for harm. When we call evil “inhuman,” we comfort ourselves with the illusion that we are incapable of it. But cruelty, conformity, moral apathy, the desire for money—these are not alien forces; they thrive in bureaucracies, in obedience, in the instinct to belong. If we insist on imagining evil as something separate from humanity, we risk overlooking the very ways it emerges in human life. We are not assured moral immunity by the Church institution, modernity and historical distance, democracy, having “correct” political views, or even so-called progress. So, by calling Nazi perpetrators monsters, we fail to ask the harder question: Under what conditions might we do the same? In what ways do those conditions already exist? Am I already participating? This recognition is one worthy of our fear, and more importantly, our vigilance: The potential for evil exists within the ordinary and the familiar.

Contemporary philosopher Richard Kearney suggests that many of the monsters and specters we fear in the world are figures we help bring into being when we demonize one another. He mentions a psychoanalyst who once advised a patient: “Before you wake up out of that dream in horror, try to look into the face of the monster pursuing you. Maybe you’ll be surprised to find that the monster is not entirely unlike yourself.”4 For Kearney, this goes beyond therapeutic counsel. We should look at those we call our enemies and recognize that they resemble us more than we would like to believe.5

With this in mind, when I opened my eyes in the morning to a view of my wall at Auschwitz, placed my feet on the floor, and opened my curtains to gaze out the window, I was keenly aware I was taking up the space of a Nazi, stepping where he stepped, breathing the same air he once breathed. As unsettling as it was, I could not reduce him to a mere specter of evil wholly apart from myself. Kearney’s words urged me to resist that comfortable distance. The thought lingered as the morning light spilled across the room, indifferent to who once stood where I now stood, from which position I couldn’t help but consider my capacity for cruelty. It was in this consideration that Tolstoy’s plea came to mind —“God, teach me how to exist, how to live, so that my life should not be so loathsome to me.”6 The plea of one Russian author was answered by the words of another. Dostoyevsky writes:

For know, dear ones, that every one of us is undoubtedly responsible for all men—and everything on earth, not merely through the general sinfulness of creation, but each one personally for all mankind and every individual man . . . Only in this conviction, our heart grows soft with infinite, universal, inexhaustible love. Then every one of you will have the power to win over the whole world by love and to wash away the sins of the world with your tears.7

Each morning, I stepped outside, walked past the gas chambers not one hundred feet from my doorstep, and passed beneath the infamous sign stating “Arbeit macht frei,” meaning “Work sets you free.” I entered a barrack-turned-office, a space once meant for destruction now repurposed as the archives of the former camp. Assigned to the Bureau for Former Prisoners, I spent the hours of my morning and afternoon examining documents, attempting to record information and restore identity to those whom the world had tried to erase. Erzsébet, Sarolta, Edith—names I thought of as I walked to the archives. They became my morning prayer, a litany repeated in step with my daily walk, which eventually became ritual. With each step, I became more convinced of the mantle non-uniquely placed on my shoulders, given by the mere fact of my being human. Only in this conviction, indeed.

This kind of responsibility, this love, begins with the way we think. Arendt describes thinking as a political and moral act, one involving the “habit of examining whatever happens to come to pass or to attract attention, of reflecting upon it and asking what it means, what it indicates, where it leads”8 Humanity seldom enjoys a surplus of reflection; the “simple and ordinary” life can be characterized by certainty and the relief in dogma that demands nothing but agreement. The kingdom of God, however, won’t be built on stock phrases, standardized codes of expression, and all the words we inherit without investigation. It is in fact built first by recognizing the invisible meanings of things.

I suggest that if thought is to fulfill its ethical potential, it should extend beyond the preservation of individual integrity toward the transformation of the social and political arrangements that sustain dehumanization. To think, then, is not simply to withdraw from the world but to re-enter it differently and perceive those things which station us firmly in our own worlds. Thought, in this sense, inspires insurgence as a mode of consciousness that resists the force of inherited or imposed certainty and reopens the world to plurality and encounter.

When thought meets reality with honesty, it reveals that our freedom is bound to the radical claim that others have upon us. I’ve noticed a tendency in myself or in our Latter-day Saint community to pray for opportunities to do good, or perhaps to acquire the “eyes to see” those around us in need. It’s a beautiful and sincere request, but one that often remains confined to the boundaries of our neighborhoods, wards, or routines; essentially, the worlds we already inhabit. In a world that remains segregated by class and economic status, Christian love demands more than attentiveness within reach; it might mean entering into the lives of those whose suffering is not adjacent to ours, or whose suffering disrupts our theological paradigm. To love as Christ loved is to cross boundaries, to descend from the safety of the ninety and nine and go where the one is lost, hurting, and possibly hard to love. So yes, we should pray for eyes to see, but also for feet willing to go, and for love that costs us something.

I don’t know if the kingdom of God will come—the day when the wolf lies with the lamb, poverty (perhaps the final structural injustice to be abolished) is no more, and evil is eradicated. I hope fervently that it will. But I find the question of whether it will come is less useful than how it might. Do I know it’s certain? No. A far more pressing question is: What am I doing to bring it about? Not enough, that’s for sure. But I do know this—the kingdom of God will only be possible when we have the thoughtfulness to confront the evil within ourselves. It will only be built by those willing to think deeply and refuse the comforting illusion that the work has already been done. Only when, in the spirit of the Confiteor, we confess before God and before one another, “I have sinned . . . in what I have done and in what I have failed to do, through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault.” And only when that confession is followed by a renewed, unwavering sense of responsibility, can we build the kingdom of God.

On my last day at Auschwitz, my colleagues at the museum gave me a small pin that says, “do something!” It references the 1942 breakout of four prisoners, one of the most dramatic escapes recorded from Auschwitz. Disguised in stolen SS uniforms and driving a captured German command vehicle, the men bluffed their way through the front gates. In his memoir, Piechowski recalls the moment at the final checkpoint:

I felt a strong knock to the back of my neck and behind my right ear the hissing voice of a monk sitting behind me: - Kazek, do something! - I came around. I opened the car door and let out a stream of military abuse towards the guard. It wasn’t enough. I jumped out of the car, vigorously placing my hand on the holster. He leapt towards the handle. Open the gate. That’s all we were waiting for. They salute us. We are leaving . . .

My colleagues gave me the pin as a token reminder that while the desperate call of Kazak’s friend, “Do something!” was directed at Kazak, we should consider it as a call to us as well, to assume a disposition of responsibility. If evil is banal, then remembrance or outrage are not enough. We are called to live extraordinarily through radical moral attention, from which costly and deliberate responsibility emerges. The pin held a message that is something of a mantra they live by, and a challenge, now, for me too.

Janai Wright is an incoming student at Harvard Divinity School. She is engaged in interfaith work within the Utah community and has research interests in phenomenology and comparative theology.

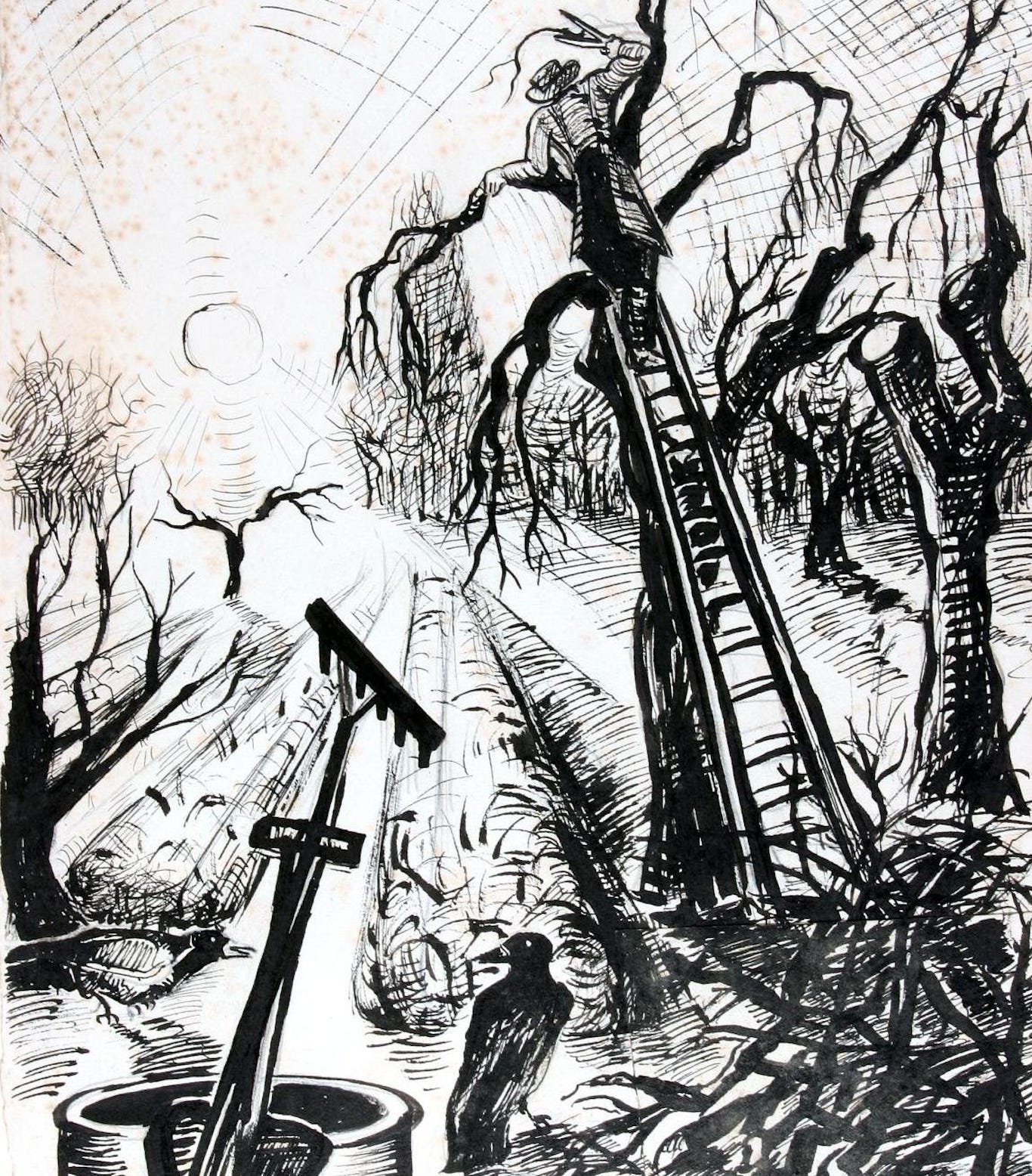

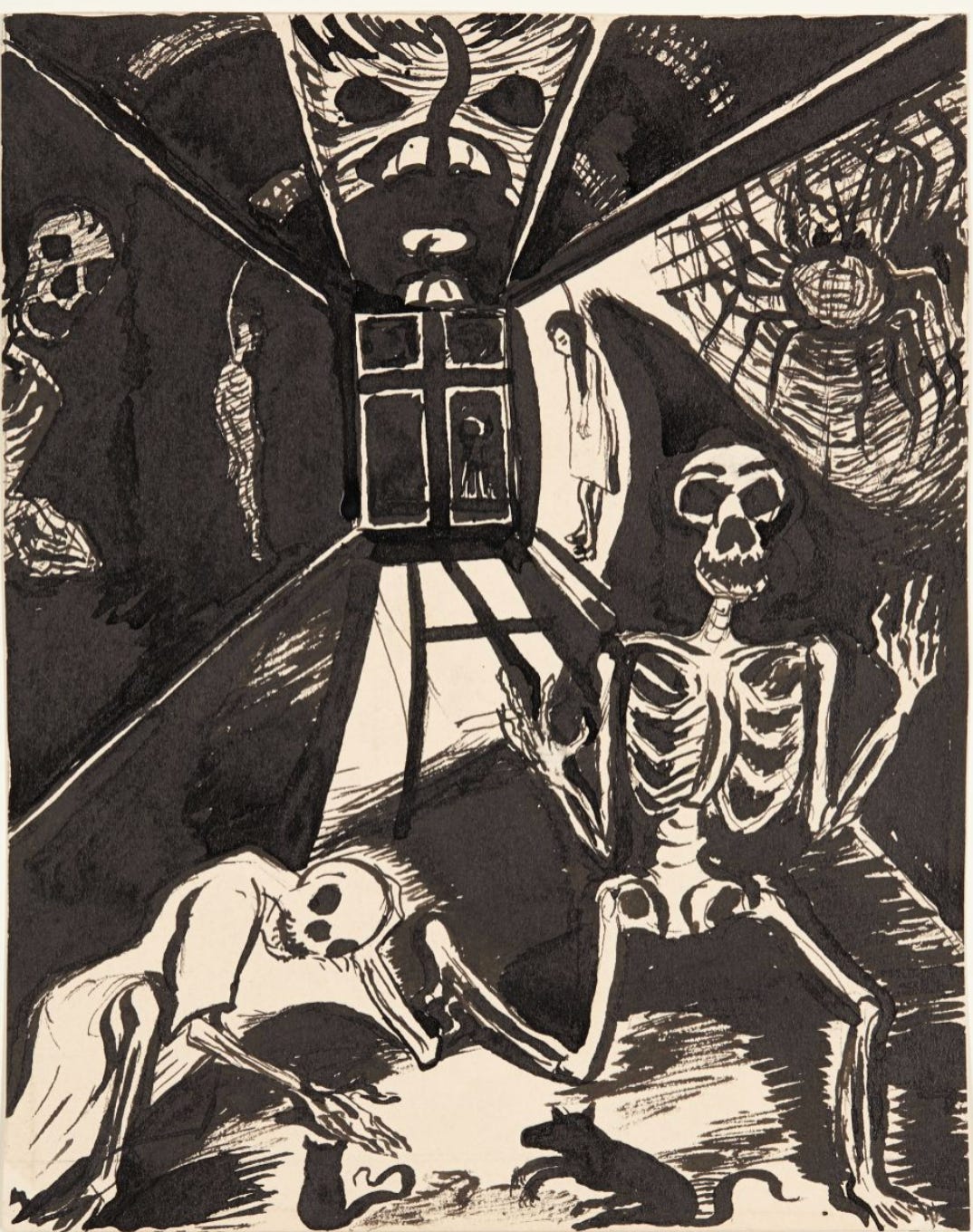

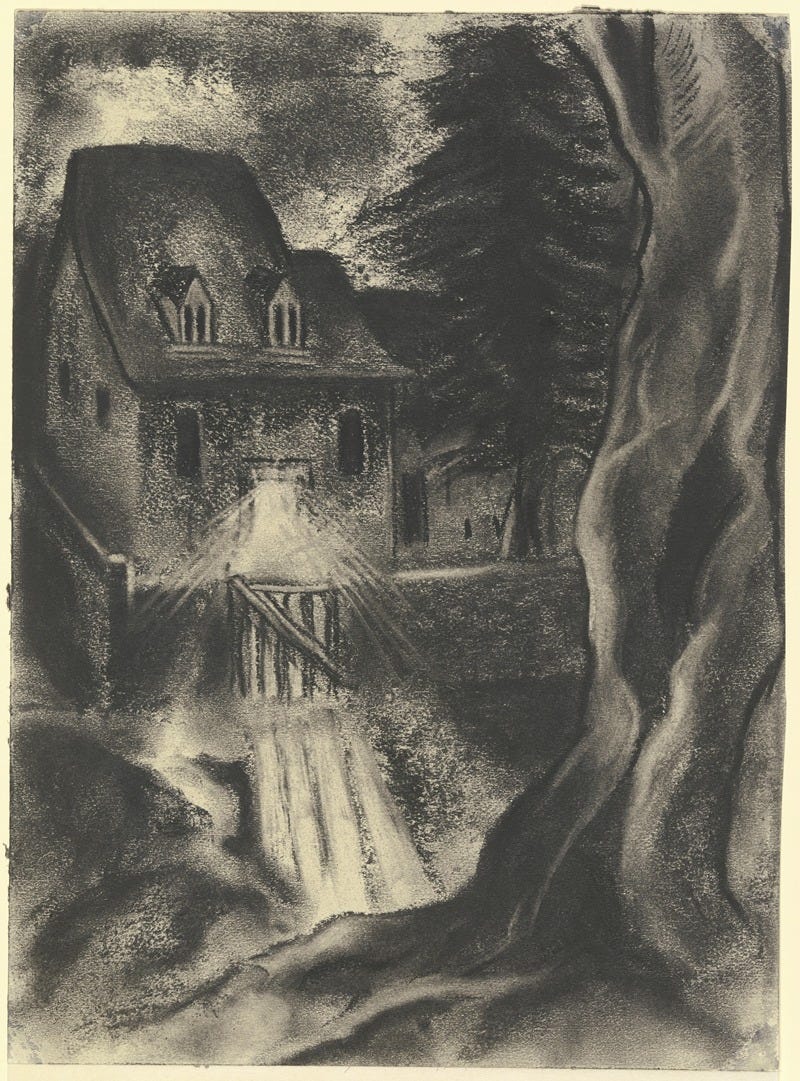

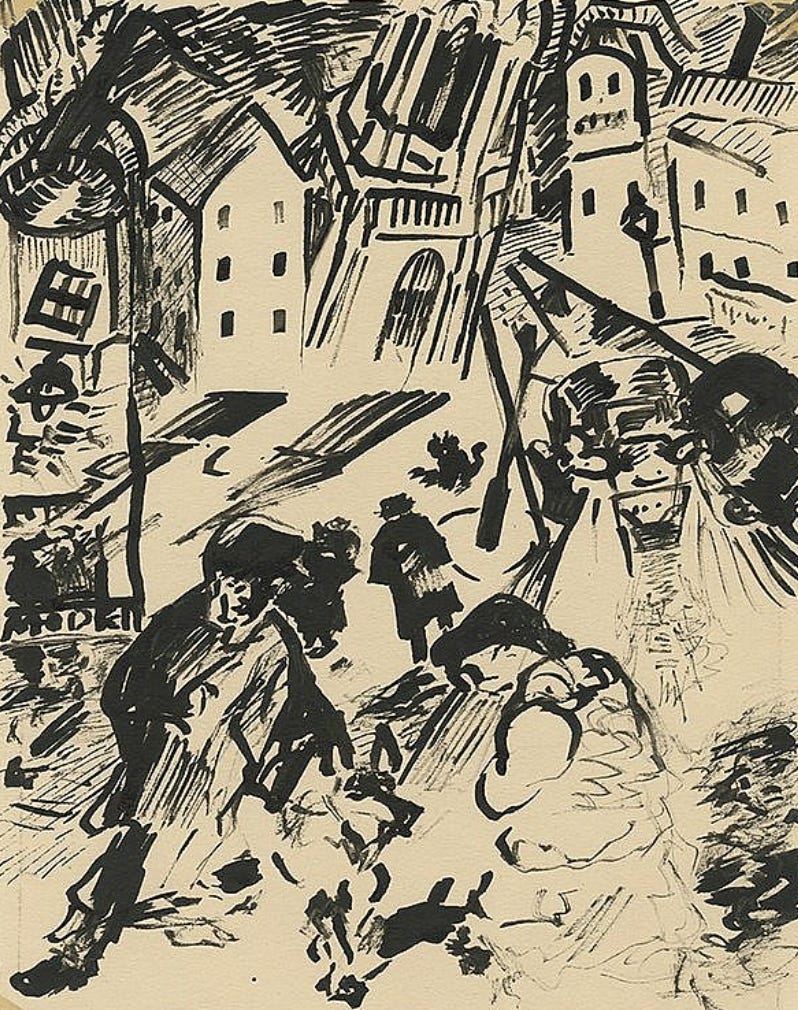

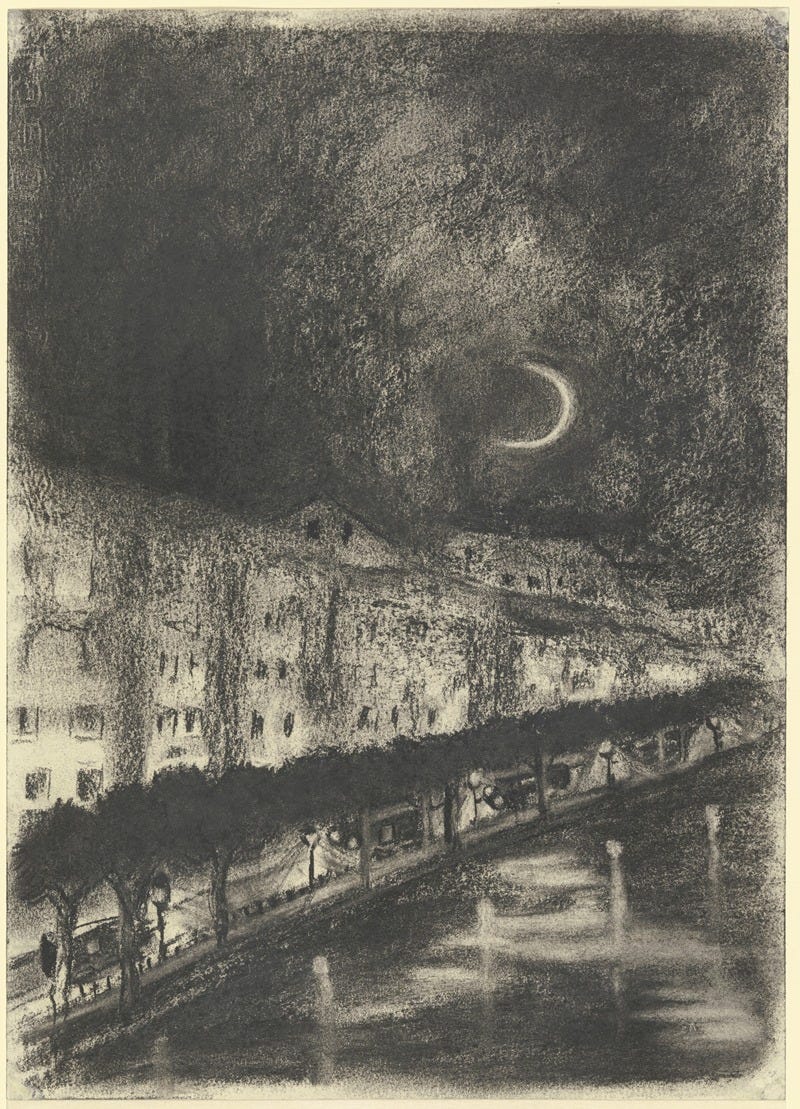

Art by Rosy Lilienfeld (1896, Frankfurt-1942, Auschwitz).

Leo Tolstoy, The Death of Ivan Ilych, trans. Lynn Solotaroff (Bantam Classics, 1981), 43.

Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (Penguin Books, 2006), 276.

James Baldwin, “A Talk to Teachers,” in The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948–1985 (St. Martin’s/Marek, 1985), 328.

Kearney, Richard, as cited in Tomáš Halík, I Want You to Be: On the God of Love, trans. Gerald Turner (University of Notre Dame Press, 2016), 47.

Halík, Tomáš. I Want You to Be: On the God of Love. Translated by Gerald Turner. (University of Notre Dame Press, 2016), 122. This is closely paraphrased from Halik’s words about Richard Kearney.

Moore, Charles E., ed. Leo Tolstoy: Spiritual Writings. (Orbis Books, 2006), 44.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Frederick Whishaw (The Modern Library, 1993), 249.

Hannah Arendt, The Life of the Mind, p. 191.