Of Rivers and Maps

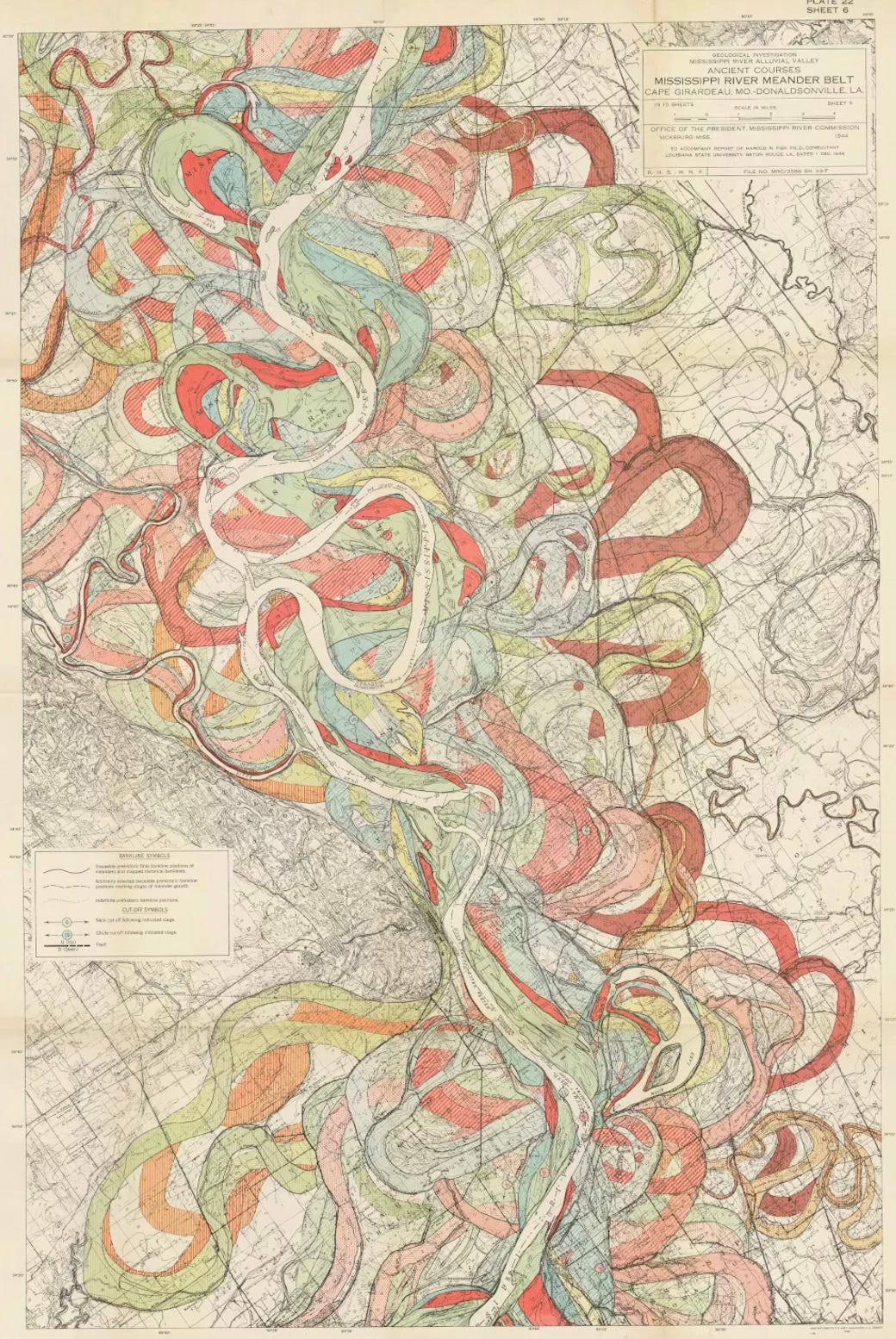

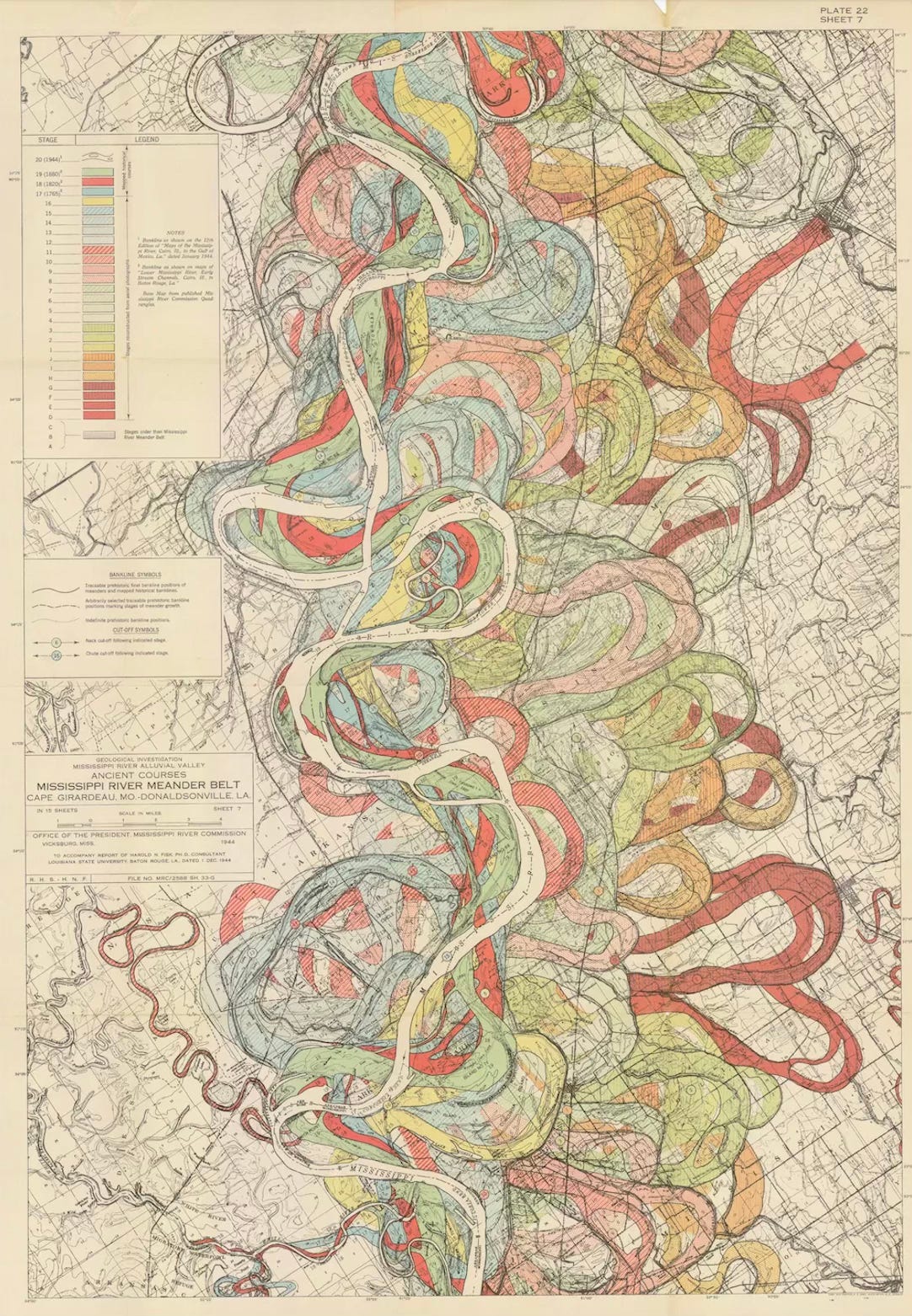

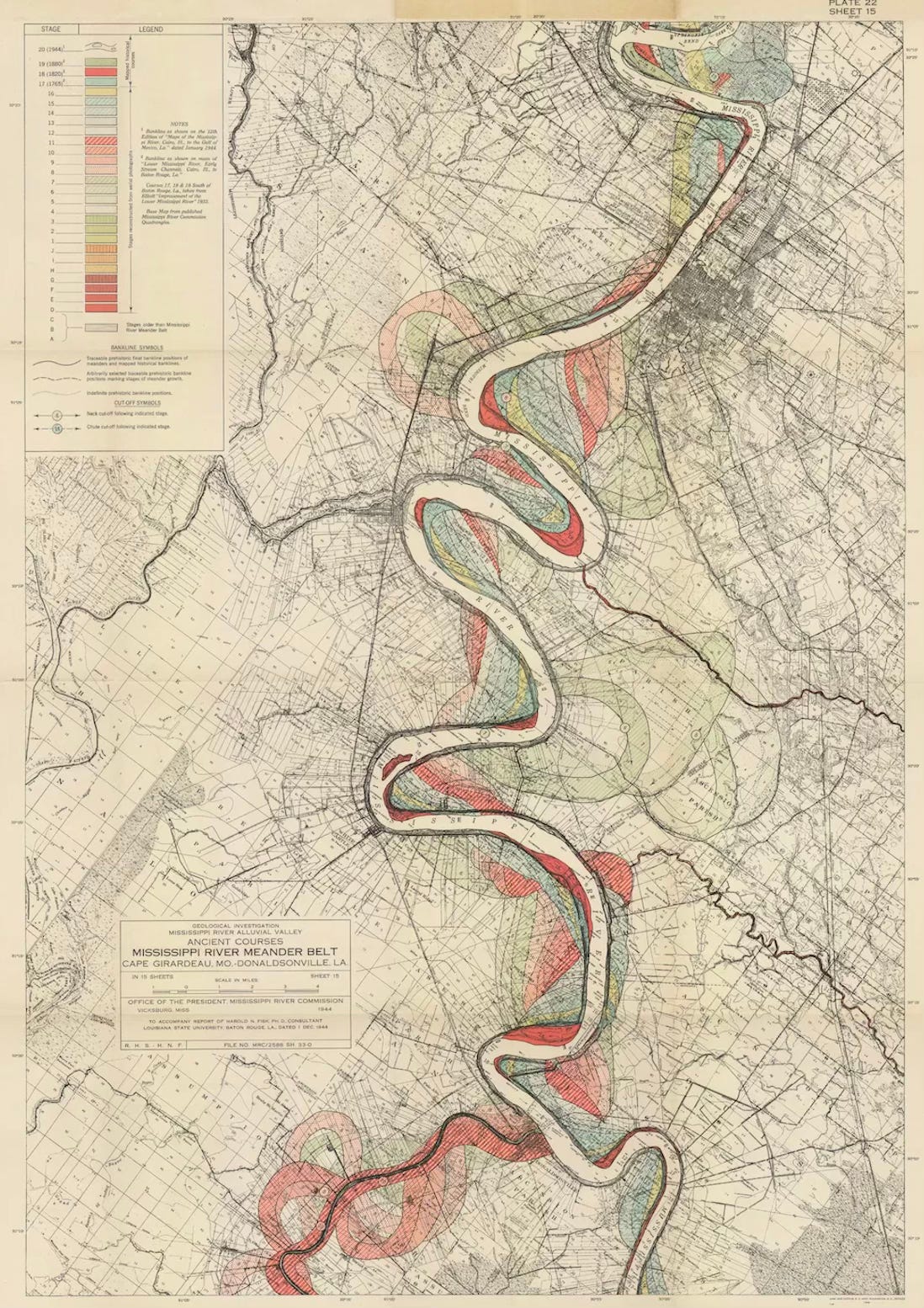

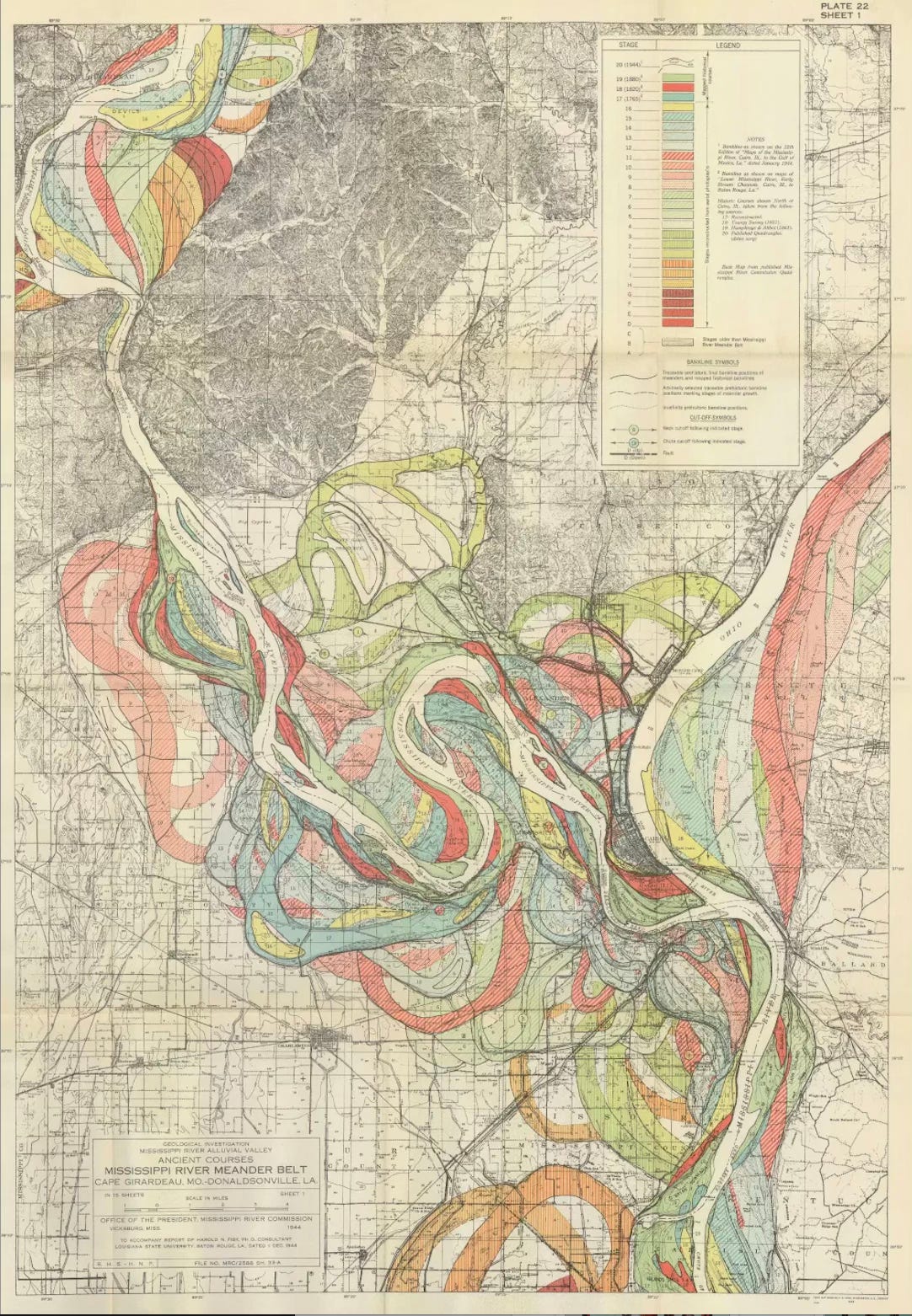

The first time I saw a copy of Wayfare Magazine, I was enthralled with the illustration on the front cover. The credit said it was a “detail from Harold Fisk’s 1944 ‘meander map’ of the Mississippi River’s shifting course over time.” Researching further, I learned that Fisk was a geologist and cartographer who worked for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. He wanted to illustrate the history of the Mississippi River’s course at a glance using different colors. For example, the course of the river at Fisk’s time is represented in beige. Around that course swirl the colors of earlier times: green for 1880, pink for 1820, light blue for 1765. If you look closely, you will see even earlier traces of where the river once flowed, dating back to prehistoric times. Something about the map stirred feelings in me, as if I were being beckoned on an inner journey to a place I had once known but lost.

Before viewing Fisk’s map, I figured the Mississippi must have flowed in basically the same pattern forever. The meander map opened my eyes to the truth of the river’s ever-changing story. The Mississippi is a huge river, stretching more than 2,300 miles through North America, at times spreading eleven miles wide. For millennia, it has provided sustenance and support for nature and humans. It is estimated that today up to twenty million people depend on the Mississippi for their drinking water.

What events could cause such wide variations in this mighty river? The Mississippi’s evolution over time involved natural forces, with the river responding and adapting to earthquakes, floods, erosion, and sediment deposits. European settlers altered the river by digging new courses to suit their needs. They cleared logjams and installed floodgate systems. They cut down the trees along the river to support the rapid development of that era. But one thing that never changes is that the Mississippi originates at a glacial lake in Minnesota and empties into the Gulf of Mexico.

I was raised by a farm boy turned metallurgical scientist and a mother who hailed from a rural community in Idaho. My life also began in Idaho and then flowed to New Mexico, where I spent my teenage years in Los Alamos, a town that provided rich intellectual experiences but left me with little exposure to economic, cultural, and racial diversity. When I headed off to college at Brigham Young University in the early 1980s, I carried with me a limited view of the world. The course of my life’s river was running much as I had expected and planned.

Next came a wedding, a temple sealing, the births of three wonderful children, and service and activity in the Church, which provided a smooth, steady flow to my life. But in midlife, I encountered rough water with the finalization of a painful divorce just weeks before our twenty-fifth wedding anniversary. This unplanned course change, followed by a second marriage, step-parenting, graduate education, and experiences as a mental health therapist, introduced nuance about people, the world, spirituality, and religion. Life had stretched the views formed during my earlier life. I found myself unsure of whether I belonged in my conservative congregation in the rural Utah town where I now live. I developed deep questions about life and faith. I began to feel spiritually lost.

Every individual’s earthly experience includes, at times, metaphorical earthquakes, floods, logjams, and trees cut down at their roots. Some life changes take us by surprise and set us on a course we never could have predicted, believed, or desired. Other times we make deliberate, carefully engineered changes. Life shapes and forms us over time, sometimes carving out deep, painful crevices that might later fill with compensating blessings. Turbulence might smooth into pools of empathy or open a path to forgiveness. I am learning to view my life and others’ lives differently. And in the process, I am finding my way back to faith.

In 2006, my father hired a fly fishing guide and invited me to go along to the Lamar Valley in Yellowstone National Park. There is always something special for me about standing in a mountain stream with the sun glinting off the water, colorful stones beneath my feet. I fished using a rod that my father had built and with flies that had been fashioned by his hands. I cherish the memory of being together, water rippling around our legs, the wind challenging our ability to cast where we aimed.

Together we have reminisced about that day many times. He insists that I caught the only fish, but I remember it was him. He is now in his late eighties. Poor balance prevents him from traversing the terrain required to reach the streams we love. My parents’ lives and mine have meandered toward and away from each other through the years, mostly due to shifts in my geographic location brought on by life events. Sometime soon, they will be even farther away from me. The courses of rivers and streams in Lamar Valley were altered significantly in the Yellowstone flood of 2022. Today it would be difficult to find the place we fished that day.

Just as aerial photography helped Fisk to see geographic evidence that aided him in piecing together the Mississippi River’s history, our Heavenly Parents, who love us, surely see the course of our lives clearly before them. They know that when a person leaves their heavenly home, there are limitless possibilities of where they might meander. That is the plan. After all, we are their work and their glory (Moses 1:39), but on our way to the immortality and eternal life that they desire for us, we are given dominion (Moses 2:28) and agency (Moses 4:3). We may take a course this way or that way. We may change our minds. We may get lost and then be found again. Our children may choose a different course than what we might choose for them, flowing away from us or away from the faith of their childhood. The hope is that they will flow back someday. But one thing that has never changed is that we originate from a premortal existence with our Heavenly Parents. And we will all make our way back home to the God who gave us life (Alma 40:11).

Now when I step into streams and rivers, reeling in and then releasing the lively, beautiful fish, I remember that Heavenly Parents often cast in life’s stream for me, catching me and pulling me close with tiny remembrances of them: a vivid sunset, a towering mountain peak, the smell of pine trees or sage, the love of my husband and family, the discovery of Fisk’s colorful map. Then I am set free to swim again in the stream of my life. These sweet encounters with Deity remind me of this quote from A River Runs Through It by Norman Maclean, where he describes his brother’s perfect casting style, watching the fly float toward the river like a bit of ash drifting in the air. “One of life’s quiet excitements is to stand somewhat apart from yourself and watch yourself softly becoming the author of something beautiful, even if it is only a floating ash.”

If we could somehow view a map of our lives and the lives of those we love, I believe it would reveal a tapestry more wonderful and captivating than Fisk’s map. I will continue to ask questions. I will open myself to meandering through the twists and turns of a faith reconstruction. I will allow my children and others I love to choose their own course. I will remember to trust that Heavenly Parents and my Savior are aware of the path that I take. I will continue to look for evidence that they are watching over us and want us to return to them.

At pivotal times in my life, others have meandered into my life to serve and to bless me. I am grateful for this. Looking back from where I am now, I see my own amazing map with twists and turns, widening and narrowing, rushing and slowing. It’s a beautiful combination of my own design and circumstances beyond my control. Maybe I am right where I’m meant to be at this time in my life’s course. Maybe we are all right where we are meant to be. The prophet Jacob in the Book of Mormon wrote, “Our lives passed away like as it were unto us a dream” (Jacob 7:26). To that, I add my belief that our lives also pass away as it were unto us a stream. And someday we will all flow Home.

Joan Rasmussen is a licensed clinical social worker who lives in Willard, Utah. On weekends, she is often in the mountains with her husband and her dog, then back home to keep up with sixteen lively grandchildren.

Meander Maps of the Mississippi River (1944) by Harold Fisk.

This is such a healing way to consider the course of our lives. I feel so comforted by this comparison to the macro-level working of the river and that new courses can always be fruitful or painful areas can filled in with love or perspective with time.

That image of where we originate from and where we inevitably flow is also helping me feel absolutely cared for by Heavenly Parents. There is nowhere that I could go accidentally or purposefully that would remove me from their guidance.