At the base of my relationship with God are my will and His: obedience and blessing, transgression and punishment, repentance and forgiveness, rebellion and condemnation. Every Christian commandment from choosing to reverence God to loving my neighbor to controlling my thoughts assumes that I am morally responsible for my actions. This free will is so basic to Christianity that Christ’s redemption of my sinful self is meaningless without it. Blessing me for good I cannot help doing or condemning me for sins I deterministically commit would be like blessing a flower for blooming or punishing a wildfire for burning. The flower can be watered and the fire doused, but the flower merits no blessing nor the fire cursing—they are not deliberately good or evil. Without moral agency, my virtue and my sin both vanish, and with them go the reason for Christ’s atonement.

This question of whether I am (and you are) morally accountable is so crucial that people have debated it for basically forever. Aristotle, Saint Paul, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Thomas Hobbes, Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill, and a host of others have argued the question, and it is still unanswered; hence, these thoughts.

Traditional Definitions

To appreciate the radical answer The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints gives, I first review a typical traditional argument for free will. Then I compare it with relevant Latter-day Saint doctrines. To do that, I think through each word in the sentence, “I can choose freely.”

Traditional “I”

In discussions of free will, “I” is each of us, individual human selves who choose freely—or not.

Traditional arguments against free will define me as consisting entirely of material matter from the world around me. Arguments in favor of free will traditionally define me as essentially immaterial: while I may be clothed in a material body, the essential “me” is fundamentally immaterial mind, spirit, soul, etc.

For me, these definitions are at the heart of the question. If I am essentially material, then I am part of the material world. Since (as far as I know) the material world operates on unbreakable laws of cause and effect, defining me as part and parcel of that world all but destroys arguments in favor of free will: like every other material object, I and my choices am simply effects of causes and causes of those causes back and back to God. Moral agency disappears into predestination.1

On the other hand, another problem arises if I am essentially spiritual. Asserting that I am essentially immaterial severs the link between me and the material world so that material causation swirls around me but does not determine my choices. Unfortunately, I then must wonder how my immaterial spirit can feel drawn to choose between right and wrong in some real-world situation. Isn’t that feeling the very essence of being affected by the material world?

Traditional “Can”

“Can” implies three prerequisites for free will. First, I must be aware of options. Second, I must be able to enact those options. Third, I must perceive some options as morally better than others.

Traditional “Choose”

“Choose” means to select and perform one option from a group. I have not chosen until I have committed to a given alternative strongly enough to give my powers to its accomplishment—until I will it so. Choosing, then, rests on my real intent, or actually attempting in good faith to implement an alternative.

Traditional “Freely”

Traditionally, for me to choose freely means I choose independent of influences external to myself; so says Aristotle anyway. However, I see a serious problem with this: if my choices are independent of external influence, they are unrelated—and thus irrelevant—to those externalities. Admitting relevance requires me to admit influence.

To illustrate, imagine I am walking a forking footpath through a pleasant garden. At each fork, I choose which way to go. Are my choices influenced by the slant of the sun, the colors or aroma of the flowers, the shade of the trees, the buzz of bees, the gravel under my feet? That is, do I consider these externalities when I choose? If so, Aristotle says my choices are not free; he says I am reacting deterministically to the traits of the garden. Aristotle (and every free will2 advocate I know of) says that to be free, my choices in the garden must be independent of the garden. Really? Do I have free will only if my choices are unrelated to the objects of my choices? What is the point of my choices then?

Traditional Free Will Floundering

I find such traditional free will arguments disastrously unconvincing; I just don’t see how I can make moral choices independent of external reality. On the other hand, I also find traditional arguments against free will disastrously convincing; my surroundings do influence my choices. Either way, my moral agency disappears: either the universe or God or my pineal gland or my parents or whatever makes my choices, or my choices are meaningless.

Radical Latter-day Saint Reconception

Thankfully, I have the doctrine of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to make sense of my moral agency and my need for the Savior. What then is the Latter-day Saint understanding of “I can choose freely”?

Latter-day Saint “I”

In Latter-day Saint thought, I am the self who chooses (freely or not), a dual being of spirit and body created by God: “the spirit and the body are the soul of man” (D&C 88:15). This appears to be a traditional immaterial definition of the self, but it is not.

Material

“There is no such thing as immaterial matter” in the Latter-day Saint universe (D&C 131:7). “All spirit is matter, but it is more fine or pure, and can only be discerned by purer eyes; we cannot see it; but when our bodies are purified we shall see that it is all matter” (D&C 131:8). Thus, the immaterial-material split does not exist in Latter-day Saint doctrine. For me, spirit is material the same as body, only finer and purer.

Essentially Uncreated

Latter-day Saint doctrine does define me as a combined spirit and body created by God, but it also defines my God-created spirit as the habitation of an “intelligence” (Abraham 3:21–22) of “light and truth” (D&C 93:36), which was “not created or made, neither indeed can be” (D&C 93:29). This doctrine is unmistakably written, “Man was also in the beginning with God” (D&C 93:29). Though God is infinitely more powerful than me, He is no older; I am coeternal with God—“added upon” by Him but not created in my essence by Him (see also Abraham 3:18–19, 26).

Innately Good and Evil

As a Latter-day Saint, I understand that my primal intelligence, my essential self, has innate potential for both good and evil (D&C 93:30–31). Note: as a Latter-day Saint, I do not believe God is the creator of evil.

To sum me up, then, as a Latter-day Saint I am a self-existent, uncreated agent of entirely material composition who is continuously influenced toward good and evil by my entirely material environment.

Latter-day Saint “Can”

Latter-day Saint doctrine agrees with traditional definitions of “can”: awareness of options, ability to perform them, and conscience. However, it makes explicit something that in traditional circles is left tacit: I cannot independently generate options. Rather, I must be attracted or repelled by competing alternatives that already exist in my environment: “It must needs be, that there is an opposition in all things. . . . Wherefore, man could not act for himself save it should be that he was enticed by the one or the other” (2 Ne. 2:11, 16). And the opposing enticements presented to me are created by God (2 Ne. 2:17). Thus, for me, “can” is explicitly bound up in responding to external influences.

Latter-day Saint “Choose”

I see Latter-day Saint thought as consistent with the traditional view that “choose” means committing to enact an option (either physically or mentally). I see this in such expressions as these:

Men should be anxiously engaged in a good cause, and do many things of their own free will (D&C 58:27–28).

Except he shall do it with real intent it profiteth him nothing (Moro. 7:6).

If their works were good in this life, and the desires of their hearts were good . . . they should also, at the last day, be restored unto that which is good” (Alma 41:3).

If we have hardened our hearts . . . we shall be condemned. For our words will condemn us, yea . . . our thoughts will also condemn us (Alma 12:13–14).

Thus, choice is not choice for me until I enact it.

Latter-day Saint “Freely”

Integrating the Latter-day Saint definitions of “I,” “can,” and “choose” with a host of other scriptures from the standard works such as 2 Nephi 2:11,14–16; Abraham 3:24–25; and Moses 7:32–33, I developed this definition of choosing freely:

The God-given ability to express my self-existent, non-derivative will in my moral choices.

This is a radically different definition of moral agency than traditional definitions. The material/immaterial schism is entirely absent, as is the contradiction between independence and relevance.

This definition seemed so radical to me that I was astonished to find that the great medieval scholastic Saint Thomas Aquinas defined God’s freedom in similar terms. God, he asserted, is free not because He can act independent of external influences but rather because He can act in complete accord with His own nature. Aquinas explained that God cannot sin, not because He is not free to sin but rather because sin is not in His nature. Since His nature is self-existent and non-derivative (i.e., not caused by anything else), acting in accord with His nature is the very quintessence of freedom. Aquinas does not speak for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but I find his explanation of Divine agency entirely consistent with Church doctrine (see Alma 29:8; Deut. 32:4; Prov. 30:5; Matt. 5:48 and see also 3 Ne. 12:48; 2 Tim. 2:13; James 1:13; 1 Ne. 7:12; Mosiah 4:9; Eth. 3:4; D&C 61:1; D&C 121:4; Abr. 3:17, and others).

Free Will Foundering Again?

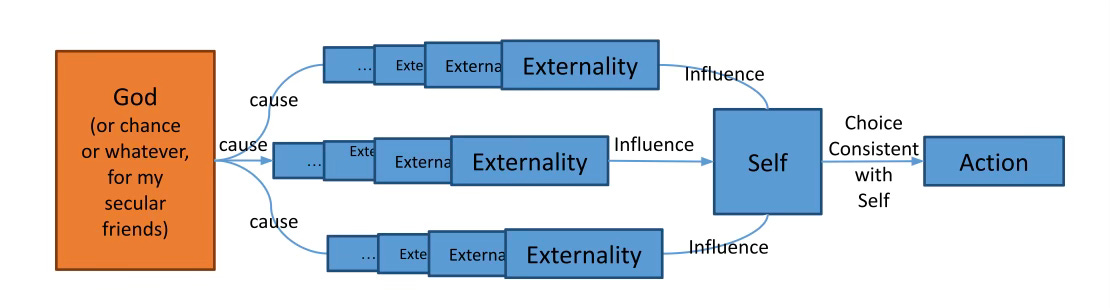

But wait. Does not the Latter-day Saint conception of free will really just admit that moral agency (as in all other choices) is nonexistent? Have I not subsumed myself in the material world, thus entangling me entirely in material cause and effect? Does not Latter-day Saint doctrine really say that human choices are completely deterministic as per the following diagram?

Self-Determinism

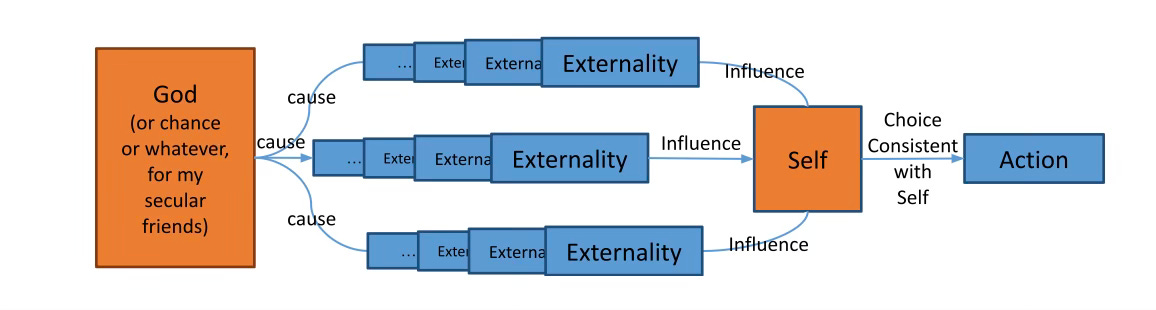

Surprisingly, the answer to this question is yes. Latter-day Saint doctrine does place me in the material world and thus squarely in the cause-effect chain along with everything else in the material world—with one crucial difference.

As a Latter-day Saint, I understand my essential self, my intelligence, to be uncreated, eternal, and self-existent. Here is the same diagram as above with a slight change to show this:

In this second diagram, my self is colored the same as God. Just as God is free by virtue of His ability to enact His self-existent, non-derivative will, so also I am morally free by virtue of that same ability; I make moral choices consistent with my self-existent, non-derivative will. To be sure, that ability is a gift of God: being infinitely more powerful than me (per Abr. 3:19, 21), He could run me like a robot—but He loves me (see John 3:16–17; 1 John 4:7–8, etc.), and so He lets me express my essential self. He has ordered the world to that end. And I do have an essential self to express. Thus, while my choices are influenced by externalities in the material world, those externalities interact with my uncaused, primordial (material) intelligence. My choices are determined, but the seat of that determinism is my self. What could be more free than such “self-determinism”? It is very nearly the same freedom that God enjoys.

From Freedom of Choice to Freedom of Will

I have found that the doctrine of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints shows me to enjoy the same general type of moral agency as God: the ability to enact my self-existent will. However, Church doctrine draws an all-important distinction between God’s agency and mine.

Mortal Agency Must be Primed

Mortal “man [cannot] act for himself save it should be that he [is] enticed . . . to choose liberty and eternal life, through the great Mediator of all men, or to choose captivity and death, according to the captivity and power of the devil” (2 Ne. 2:16, 27). As a mortal, I must be presented with choices in order to exercise my agency. I am not able of myself to create the alternatives among which I choose. God provides the alternatives, and only then can I decide which is most enticing.

Divine Agency is Independent

God’s agency is different from that: “There is nothing that the Lord thy God shall take in his heart to do but what he will do it” (Abr. 3:17). That is, God has the power to create whatever He chooses. God does not need externally provided alternatives; indeed, He does not use alternatives at all. He knows His will, and He enacts it. Being omnipotent and omniscient, He does not weigh alternatives as we mortals do. We seek externally provided opposition/alternatives; God comprehends everything everywhere all at once (see D&C 38:1–2).

Freedom of Choice Evolves into Freedom of Will

As a child of God, I have the potential to become like Him (Rom. 8:16-17; 2 Pet. 1:4; D&C 132:20). I believe this means my agency can become like God’s. Here is how I conceive that happening. I start out not knowing my own mind, so God, knowing my potential to become like Him, develops my self-awareness of my own will as I grow.

In premortality, God gave me two alternatives: agency through Jehovah or slavery through Satan (Abr. 3:27–28). I (and everyone born into mortality) chose agency, and because of this, I am said to have “[kept my] first estate” (Abr. 3:26). As an infant newly born into my mortal “second estate” (Abr. 3:26), I am presented with the relatively small (but still enormous) task of learning to use my body. As a toddler, I begin choosing in the larger context of imitating my parents and interacting with siblings, toys, and other items in my home. Then my context enlarges again with neighbors, church, school, etc. Then God gives my choices a huge boost with adulthood, jobs, marriage, and children. Then come old age, death, and the spirit world—each with its characteristic set of choices to help me identify my desires and develop more awareness of my will.

And so it goes. God asks me, “What do you want?” He then asks, “What do you really want?” And He continues to ask, “What do you still want?” The Book of Mormon puts it this way: “God granteth . . . that good and evil . . . come before all men . . . and . . . to [every man] it is given according to his desires” (Alma 29:4–5). This even continues in the world of spirits after our mortal death: “The gospel [is] preached also to them that are dead, that they might be judged according to men in the flesh but live according to God in the spirit” (1 Pet. 4:6).

In my conception of growth toward divine agency, the proving and improving of my own desires (see Abr. 3:25) comes to fruition in the Resurrection, when God fits me with a tailor-made, immortal body exactly customized to do my will as developed and revealed to me in mortality and the spirit world: “I, the Lord, will judge all men according to their works, according to the desire of their hearts” (D&C 137:9) and “ye shall receive your bodies, and your glory shall be that glory by which your bodies are quickened . . . to enjoy that which [ye] are willing to receive” (D&C 88:28, 32).

Conclusion

So here it is: I think Latter-day Saint theology rejects old, fruitless arguments about free will by showing that they are founded on a misdefinition of the self. In the Latter-day Saint world, I am essentially uncreated and eternal, endowed by a loving God with joy-producing or joy-limiting power “to act for [myself]” (2 Ne. 2:26), to express my self-existent, non-derivative will in my moral choices. I am thus a tiny, God-beloved uncaused first cause in the image of the Great Uncaused First Cause (to use Aquinas’ term). As a Latter-day Saint, I situate my self-as-moral-agent within the cause-effect chain of the material world—indeed, my theology admits no other kind of world—and hence see myself as entirely relevant to and involved in the consequences of actions, which is to say, I effect and am affected by the (entirely material) world. God allows me to enact my self-existent will within the protective bounds of Christ’s Atonement (see Isa. 61:3), and so I am morally culpable for the good and bad I choose. As the Book of Mormon prophet Lehi concluded, I am

free to choose liberty and eternal life through the great Mediator of all men, or to choose captivity and death according to the captivity and power of the devil; for he seeketh that all men might be miserable like unto himself. [Therefore] look to the great Mediator, and hearken unto his great commandments, and be faithful unto his words, and choose eternal life according to the will of his Holy Spirit (2 Nephi 2:27-29).

This is how I see God loving me moment to moment. Do you see God’s love this way too? I hope so.

Thomas Hilton has served since 2003 as chairman of the Management Information Systems Department in the College of Business at the University of Wisconsin—Eau Claire. He received his B.A. degree in English composition and literature and his Ph.D. in instructional science and technology with an emphasis in computer information system development, both from Brigham Young University.

Art by Ivan Shishkin (1832–1898).

I think protestant reformer John Calvin and his spiritual descendants are at odds with the whole rationale for Christianity. Calvin asserted that all-powerful God created the human race as totally depraved beings (his words, not mine) who are incapable of choosing good; why He chooses to save a few of us is a mystery. Being created out of literally nothing but God’s mind and will, we horrible humans are simply among perfectly-good God’s effects, and so blame for our nature and behavior are His, not ours. Salvation and damnation become inevitable consequences of God’s inscrutable choice, and God sending His Son to die for the sins of humankind becomes an arbitrary filicide.

Some say that God made us free not evil, but I do not think this helps at all: even cutting the marionettes’ strings, the Puppeteer remains their creator, the crafter of their every ability and their whole environment. Others blame human depravity on Adam and Eve’s disastrous fall to the serpent’s temptation in Eden, but all-knowing God created all that as well.

I’m referring here to “libertarian” free will. This contrasts with “compatibilist” free will, the idea promoted for centuries and still widely accepted today that we can call predetermined choices free because that is how they feel.