For years I had assumed that my relationship with libraries and antiquarian bookshops was quite separate from my human relationships—my loving ties with family, close friends, work colleagues, and neighbors. After all, the time I’d spent surrounded by books in my office required me to suspend all human conversations, and the time I’d spent in conversation with others necessarily took me away from my books. I cannot offer an exact date for when the penny dropped, and when I realized these worlds were actually not-so-very-distinct, but I am convinced that two significant, and yet quite different, friendships played an important role in this. Both friendships sprang up in the very same town in Somerset, England.

One friend was initially a friend of my parents who later took a deep interest in the progress of my studies and would comment enthusiastically on a Sunday School class I taught when I was a doctoral student at the University of Oxford. For the purposes of this essay, I shall call him Mr. Jones. The other was an antiquarian bookseller I befriended before I commenced undergraduate studies at the University of Bristol. His name, Mr. Nisbet, was no secret to his friends and customers. As very different as Mr. Nisbet was from Mr. Jones, both affected me in profound ways.

I was always struck by the generosity Mr. Jones displayed in his interactions with others in his community. He taught early-morning seminary at his local congregation and encouraged young people to lift their sights, expand their minds, and broaden their horizons. He worked at his town’s YMCA and developed positive ecumenical relations during a particular religious moment characterized by skepticism (in terms of how other Christian traditions viewed his personal faith). He was remarkably athletic in his day and taught many young athletes the importance of sportsmanship, personal discipline, and strong work ethic. And, after observing my own academic development and attending the Sunday School classes I taught for a brief period, he demonstrated a wonderful openness to new thought and ideas.

Each time he attended one of my lessons, Mr. Jones would find me afterwards and catch me by the arm to tell me with great emotion what had been opened to his mental view before imparting his unique perspective of the world to me. Before I left the levels and shires of England to embark on my current position at the Maxwell Institute at BYU, I visited with Mr. Jones. Now weakened by the ruthless effects of Parkinson’s disease, and having only enough energy for me to sit with him a while, he expressed his unparalleled excitement for the next part of my own life’s journey. To his faith-affirming openness and generosity, I responded with the human hug of friendship. And as we bore each other’s fears and excitement together, in the very same space, we parted ways—but not in spirit.

Mr. Nisbet lived through the same decades of the twentieth century into the twenty-first, only a couple of miles from Mr. Jones. I’m not certain they ever met. But at a similar time to my developing friendship with Mr. Jones, Mr. Nisbet allowed me to accompany him on part of his life’s journey as he read, bound, and sold books. He was a renowned and respected bookseller in Somerset—and our relationship worked rather well. He sold books, and I bought them. Beyond this, however, Mr. Nisbet was also a wonderful man who was integral to the life of his local community. Not only were the towering bibliographic walls in his eccentric bookshop to be treated as old friends but he, by his very nature, was also a good friend and neighbor to those who lived in relative proximity to him. I spent many afternoons chatting to him as he sorted books, smoked cigars and pipes, and assisted his customers. I remember him allowing one customer to pay for items in installments. I remember him providing book-sorting work to another man who had suffered a series of mental health challenges. I remember him assisting an elderly neighbor with the sale of her house, to ensure she wasn’t taken advantage of. Over the course of a few years, our friendship grew. When I moved away from Somerset, the news of his declining health—and later death—reached me. Although his bookshop has long since been lost to the death we call UK property development, and his body has gone the way of the earth, his voice of kindness still rings out in my ears.

Mr. Nisbet inspired my fondness for books, and Mr. Jones reinforced my pastoral sensibilities. For the longest time, I always thought these two things, “books” and “humanity,” were entirely disconnected. At least in my mind, people’s relationships with their personal book collections can sometimes be defined by bibliometrics. The act of endlessly counting and sorting reading materials, and considering progress made wading through massive repositories of knowledge in the hermitical library, can almost be considered as an exclusive mark of honor or intellectual achievement—one that sets one human apart from all others in their literary greatness. But even if we were to dwell on the extreme end of the bibliographic spectrum, would it be true to assert that the most bibliometric, even misanthropic, reader is alone in their reading? My instinct had been to say that they are—but my own experience of reading, and the encounters I have had both within and beyond the realms of the text, teaches me otherwise.

The perceived tension between book collecting and human interaction can be loosened by placing my friendships with Mr. Nisbet and Mr. Jones in conversation with a short reflection written by Umberto Eco. In this reflection, Umberto defends his own sizable private library. In addition to being an avid writer, Umberto Eco was a prolific reader. This, by his own admission, poured into his home life. Having guests enter his house and encounter the masses of books he had accumulated seemed to occur frequently. Inevitably, at some point, these visits would lead to the question: “What a lot of books! Have you read them all?” As Umberto indicates, there are many responses that can be offered in such a situation, and he is not short of a repertoire of retorts. Inspired by Roberto Leydi, Umberto first suggests throwing back the answer: “And more, dear sir, many more”; but goes on to settle on his favorite: “No, these are the ones I have to read by the end of the month. I keep the others in my office.” Of course, Umberto’s imaginative responses must be understood in the context of his dry wit and command of expression. Only in satire does one realize that he grapples with the reading of infinity! As Umberto himself remarks: “Confronted by a vast array of books, anyone will be seized by the anguish of learning, and will inevitably lapse into asking the question that expresses his torment and remorse.” In this, Umberto turns the sheer vastness of the library on anyone, including himself. A similar sentiment is expressed by Terryl Givens, who, during a childhood trip to a bookshop with his father, became excited at the prospect of new knowledge and began snatching at eclectic titles to purchase. However, it wasn’t long before Terryl became aware of the massive and looming reality of the shop’s collections, leading him to abandon his previous hopes and return the titles to the shelves. In his words, he recounts: “I remember vividly the next moment, when I returned all the books to the shelves and went to the car, despondent and defeated by the impossibility of it all.”

With Umberto’s comical and sobering episode in mind, and Terryl’s comparable experience, I feel compelled to ask myself the following question: why do we collect books at all? In formulating a response to this, it is important to realise that Umberto presents an outsider human to his readership, to whom book collecting is a foreign phenomenon. This creates a tension between Umberto’s bibliographical fortress and his inevitable interactions with humans from the outside world, and it suggests a chasm between “books” and “humanity.” Indeed, the very presence of an actual human figure intruding into the space of his library initially provokes anxiety in Umberto. He thinks through several responses designed to deflect his own perceived relationship with books, which he then goes on to lament. And perhaps his sobering confession of being “seized by the anguish of learning” leading to “torment and remorse” is exactly that—the inability to make any real progress in the library, even the private library. Perhaps it is, as Terryl suggests, “the impossibility of it all.” Or perhaps, for Umberto, it is something more than that. Perhaps Umberto is both emphasizing absurdity and profundity around the question of why we collect, pushing us instead to consider the very nature of the book itself and how this might ironically connect to human lives (rather than discourage human lives from entering in).

Returning briefly to Terryl’s experience at the bookshop, I find it intriguing that the same feeling of hopelessness he first experienced as a child still follows him to this day. At other times, however, his book collection leads him in the direction of humanity. Indeed, his own private library—composed of books he has personally sought out, negotiated, handled, and sorted—presents to him the impossibility we greet in Umberto. In Terryl’s own words: “At times the old hopelessness descends even now.” But in another breath, the impossibility of making any progress through infinite volumes provides a portal to another realm of thought—one where human actors live on as if unaffected by the permanence of the grave. As Terryl goes on to explain: “At other times, I run my hand along the bookcase and retrieve a volume acquired decades ago, never opened until this moment. And I marvel anew at how fresh and alive a voice sounds, that so patiently waited in quiet neglect over the passing years.” The sentiment contained here reminds me of an observation made by the Anglican theologian Elaine Graham—namely, that a phenomenon’s “primary distinguishing feature” is often its soberingly “human context.” After all, what could be more human than our collections of books that beautifully preserve the human voice?

So why do we collect books at all? Well, it’s obvious that we collect books to read. But maybe it’s less obvious that we collect books to connect ourselves more fully to the human world rather than to retreat from it. The infinite library reminds me that books are distinctly human, created by human hands and filled with the complexity of human life and thought. Any progress one makes in the library is, by its very nature, an act of collaboration in a community that is distinctly human. Just as it would be impossible to read all of Mr. Nisbet’s book collections, and downright absurd to expect that he or anyone had read all of the countless books in his antiquarian bookshop, so too would it be an impossible task to meet and sit with all the humans that make up the town in which his bookshop was once situated. The sheer impossibility of the task of knowing everyone in a town would never stop a human from continually encountering other humans and deepening relationships. So why should the impossible dimensions of the private library distract from the fact that reading books provides a way of connecting with human voices, both living and dead?

This realization prompted me to feel less anxious about the metrics of collecting and reading, or of memorizing and regurgitating. It helped me recognize the profundity of Umberto’s reflection—that reading all of our books is not only impossible, but contrary to the basic nature of the book. So now, I am more inclined to view the library as a portal to human interaction. Reading becomes a way of connecting to human voices far removed from the reader, whether through distance or death. As for writing, well, that becomes a way of giving voice to human lives that might otherwise be lost to the same inevitable destructive forces.

The lives of Mr. Nisbet and Mr. Jones may never have crossed directly. But I hope by this point, my own reader will understand why I am convinced that Mr. Nisbet’s relationship with his books was a distinctly human affair—pushing him further into the human world inhabited by Mr. Jones. I now recognize that the seemingly solitary hours Mr. Nisbet spent hidden away surrounded by biblio-piles not only enriched his ability to interact with the human world but was also the embodiment of it. The lives of both friends were spent continuously immersed in a sea of human voices, whether within or beyond the written word. From this, I suppose books were never quite what I once considered them to be. Ink pressed into the paper page, or scribbled across the manuscript folio, is not there to enable the reader to advance in their own literary brilliance or to excel beyond the intellectual capacity of others measured on the bibliometric scale. No. Rather, these marks we labor to decipher are mere symbols that connect us to a broader human community, enabling us to transcend the book itself and enabling the human lives therein to transcend the necessary evils of mortality.

I began by writing about the beautiful impact of two human friendships on my own life and the lives of their respective communities, before indicating the way death, sickness, and declining health tragically affected them. By virtue of writing these small, connected paragraphs—and making the connection between “books” and “humanity”—I live in the hope that the human impact of Mr. Nisbet and Mr. Jones is not merely locatable in the human spaces their radiant lives once occupied. Rather, through these few words I provide here, detailing something of their own human stories, my intent is that the written word fulfills its most noble purpose. In the face of death and sickness’s inevitability, the written word transcends the hospital and grave, and through it human life lives on.

Timothy Farrant is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Maxwell Institute, having previously worked in chaplaincy and higher education in the UK. He grew up in the southwest of England and studied at Bristol, York, and Oxford.

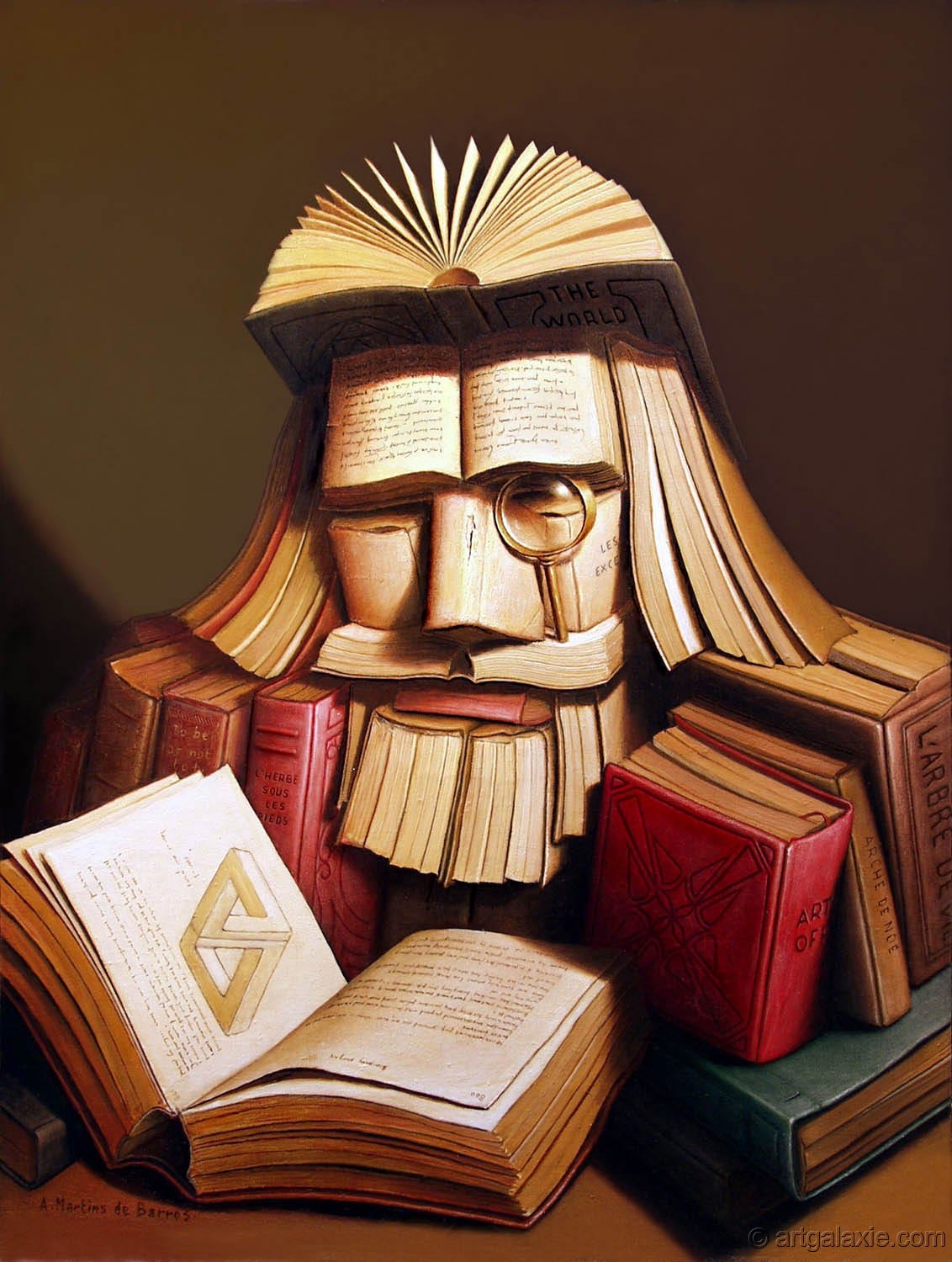

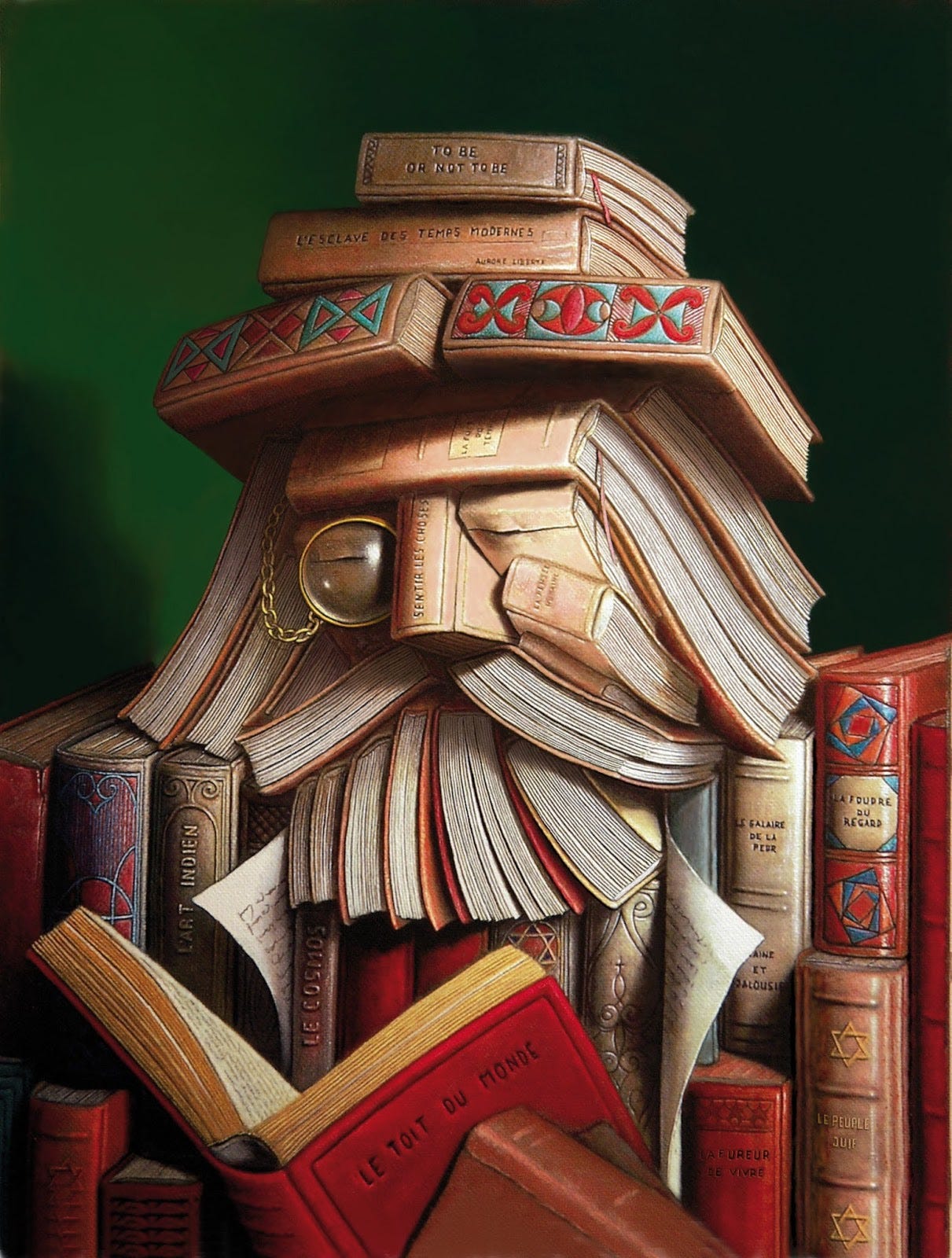

Art by Giuseppe Arcimboldo and Andre Martin De Barros.