Journeys of the Spirit

A History of Christian Pilgrimage

“Faith is not the clinging to a shrine but an endless pilgrimage of the heart.” —Abraham Joshua Heschel

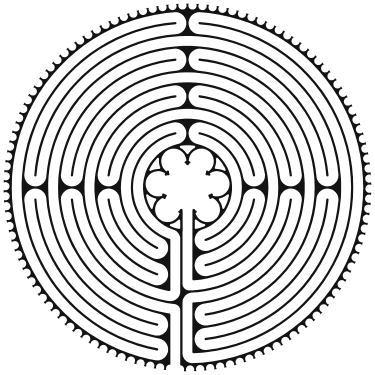

My hopes for the future began in the center of a labyrinth. It was December 2010, and I had flown to Paris to meet my girlfriend Mariya, who was finishing a semester abroad at the Sorbonne. I suggested we take a day trip to Chartres Cathedral to see the stained-glass windows. The train ride from Paris to Chartres is about one hour, and every five minutes or so I would reach into my coat pocket to confirm that the small box containing an engagement ring was still there. Once we arrived, I took Mariya up the pulpit stairs so she could see the secret pattern on the stone floors of the church—an elaborate circular maze in the center of the nave. I suggested we walk it together. It took longer than expected, because we were continually stepping over the cathedral chairs that covered it. With each step my heart pounded louder until we finally stood at the center and I went down on one knee.

Pilgrims have walked the Chartres labyrinth for more than eight hundred years. It was built around 1215 to fulfill a need. The Crusades made the journey to Jerusalem too dangerous at that time. To meet the pent-up demand for pilgrimage, seven European cathedrals, mainly in France, were designated as the “holy land.” People would journey through the seven cathedrals and end at the Chartres cathedral. The Chartres labyrinth became the final stage of the journey, serving as a symbolic entry into the celestial city of the New Jerusalem. The most devout pilgrims even completed the labyrinth on their knees as an act of penitence.

But pilgrimage hadn’t always been so popular among Christians. The word pilgrimage comes via the French pèlerinage, from the Latin terms peregrinus, “foreign,” and per ager, “going through the fields.” It is a journey away from the comforts of home in search of transformation. For ancient Greeks and Romans, pilgrimage was an integral part of religious and cultural life. Their journeys were generally made to oracles—most famously at Delphi—in hopes of gaining insight about their future. Health, too, was a motivation. Travelers visited sanctuaries associated with deities such as Asklepius, the god of medicine, who could be petitioned for a cure. In these cases, specific locations were believed to be sites of divine power.

For Jews, the city of Jerusalem was a center of pilgrimage, a place where God could be encountered in a special way at special times. Pilgrimage to Jerusalem on the three feasts of Passover, Sukkot, and Shavuot became a requirement for all male Israelites. During periods of exile, pilgrimage to Jerusalem took on additional emotional and spiritual significance.

But Christians believed that God’s spirit was not limited geographically and could be found anywhere. How could an omnipresent God be more accessible in one place than another? As Jesus taught, “where two or three are gathered together in My name, there am I in the midst of them.” Gregory of Nyssa pointed out that Jesus never commanded his followers to go on pilgrimage and stated firmly that “Change of place does not effect any drawing nearer unto God.” Jerome declared: “Nothing is lacking to your faith although you have not seen Jerusalem.”

In any case, there was hardly anything to see at Jerusalem. The occupying Romans destroyed the Temple in 70 AD and the whole city was razed following a Jewish revolt in 135 AD. It was renamed Aelia Capitolina and a temple to Venus was built on the Temple Mount. Jerusalem, the city of God, seemed to have been obliterated.

But even had the holy sites of Jerusalem not lain buried under rubble, critics warned that “place pilgrimage” involved unnecessary expense and dangers, the abandoning of daily responsibilities, and might even (away from watchful eyes) expose participants to temptation. Instead, Church Fathers emphasized that Christian life itself was a “spirit pilgrimage” from the illusory nature of the material world to the real world of the presence of God. In Hebrews 11, Paul exhorted his readers to follow the example of Abraham, who “by faith set out, not knowing where he was going [and]…sojourned in the land of promise, as in a strange country…and looked forward to the city…whose architect and builder is God.” Cyprian, bishop of Carthage, wrote, “We should reflect constantly that we have renounced the world and as strangers and foreigners we sojourn here for a time.” Nobody followed this counsel more devotedly than the desert monastics, who sought confinement within the walls of a cave, cell, or cloister, so that their spirits might journey more freely towards an “interior Jerusalem.”

The day of my proposal wasn’t my first visit to Chartres. As a freshman at BYU I had been so desperate to leave Provo that I signed up for the winter semester Paris study abroad. The program was led by the historian of Europe Craig Harline, and the cohort was comprised of twenty-four girls…and me. Favorable odds to be sure, but I was too busy being a moody existentialist to take proper advantage.

I loved everything about France: the conviviality of cafés, the endless treasures in the museums, the pleasures of being a flâneur. But it was our group visit to Chartres where I encountered feelings that were beyond articulation. We were led around the church by a British guide who had come in her twenties and decided to stay until she had uncovered of all of its secrets (which forty years on, she assured us she still hadn’t). As we entered, I was immediately astonished. Religious spaces in my life to that point had been brightly lit, spotlessly clean, modern, and visually spare. Chartres Cathedral was the inverse—dark, melancholy, grimy, ornamented, ancient. And yet I found myself overcome by the deep holiness of this place, by the faith witnessed by every stone carving, every illuminated window pane. In need of solitude, I left the group to wander in silence, drawn inward to a place of contemplation beyond words. I returned just as our guide revealed the labyrinth on the floor.

Despite what I felt in Chartres, or perhaps because of it, after several months of life in Paris, and with my mission departure date approaching that summer, I had begun to question fundamental assumptions about my religious identity and future. How was it possible that in all the world, I happened to be born into the one true church? What if every religion is myth? Racked with such severe doubts, but anxious to do right, I committed to reading the entire Book of Mormon in the final month of the semester. Each night in my small attic room in the Parisian suburb of Le Vesinet, I made my way through the pages, increasingly enthralled by the sublime tragedy of a doomed people. When I came to Moroni 10:3, I felt as though the book had been written just for me, now, Zach in France in 2002. I knelt, addressed God in a trembling voice, and was immediately bathed in waves of divine presence.

Despite the many theological and pastoral objections to “place pilgrimage,” the urge to walk the paths Jesus had walked proved irrepressible. In the fourth century, the Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity. Used to the pilgrimage-friendly ways of Roman religion, he dispatched his mother Helena to Jerusalem with a blank check from the imperial treasury and a mandate to create a Christian sacred geography. She arrived in about 326 CE and wasted little time setting things in order. According to tradition, Helena went to the Temple Mount and ordered the temple dedicated to Venus torn down and the site excavated. Soon, three crosses were discovered. To confirm the true sanctity of the discovery, Helena asked Bishop Macarius of Jerusalem to bring a woman near death to the site. When the woman touched the first and second crosses, her condition did not change, but when she touched the third and final cross she suddenly recovered. The True Cross had been found and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built on the location.

If you build it, they will come. The pilgrims came, full of enthusiastic devotion. St. Jerome described the intense emotion of one pilgrim, a wealthy widow from Rome named Paula: “She fell down and worshiped before the Cross as if she could see the Lord hanging on it ... Her tears and lamentations are known to all Jerusalem.” In addition to Jerusalem, Rome, and later, the grave of St. James (Santiago de Compostela) in Galicia, Spain, became the primary destinations for medieval pilgrims.

The witness I had gained in Paris of the Book of Mormon had been strong enough to justify serving a mission, but once I returned, familiar, nagging questions resurfaced, like little weeds coming up through cracks in a sidewalk. Why is there no evidence of ancient Hebrew people in the Americas? Why does the Book of Abraham appear to be a complete mistranslation of the Egyptian papyri? I scoured the internet each night for answers. With some dextrous interpretive flexibility gained from caring BYU mentors, I found ways of limping forward. But when I read about Joseph Smith, Fanny Alger, and the sordid practices of early polygamy, I felt my entire world crumbling in real time. I fell onto the floor of my house, overcome by cosmic vertigo, feeling as though I were falling through space with no hope for a landing.

Although devotion may have been the most common motivation for pilgrims, others emerged in time. Some sought physical or spiritual healing; others sought to purge public or private sins. Starting in the thirteenth century, a judicial sentence for convicted criminals often came in the form of a forced pilgrimage. Between 1350 and 1360, the port city of Ghent in northwest Belgium sentenced 1,367 convicted criminals to go on pilgrimages to 133 different sites. If the criminal had committed murder, it was common to hang the murder weapon around the convict’s neck for the duration of the pilgrimage. Those convicted of heresy often had to wear two yellow crosses on their front and back. The criminals were expected to collect signatures at all the shrines visited as proof that they had been there. Sometimes, as Chaucer writes, the punishment for these criminals was even more humiliating: “When a man has sinned openly, of which sin the fame is openly spoken in the country... common penance is that priests enjoin men in certain cases, to go, peradventure, naked in pilgrimages or barefoot.”

Humiliation and blisters weren’t the only dangers of pilgrimage. In the ancient and medieval worlds, policing outside of large cities was paltry and the risk of attack by bandits or wild animals was high. The ubiquity of the pilgrim’s walking staff was in part because it was a handy weapon. Disease, starvation, and dehydration were also genuine threats. The risk of death was so real that before pilgrims left home, it became a requirement that they pay all debts, make a will, and apologize to everyone they might have offended in the past. Pilgrims would often journey in groups, keeping one another safe from harm.

Losing faith has a particular quality of pain. Not sharp, not acute, but rather a dull thrum of despair, a gray soot covering the light of life. Alone, disoriented and depressed, I focused on finishing my degree and reconstructing my life’s narrative now that the script I had inherited had suddenly become blank. I graduated in April 2009 and won a yearlong fellowship to a Washington D.C. think tank. On a muggy August, I rode the comically long escalator out of the Dupont Circle metro station, suitcases in tow, and stepped into my new, wide-open life.

Perhaps out of muscle memory or to avoid upsetting my parents, I continued to attend church most Sundays. And at first, novelty and career ambition kept the deeper questions of my soul submerged. But by January, the fragile peace treaty I’d signed with my psyche came undone when I unexpectedly fell deeply in love with a friend, Mariya. She was the daughter of a prominent Ukrainian LDS pioneer and leader, Alexander Manzhos, and fully intended to walk in the faith of her father. Torn between integrity and love, I could no longer defer a decision about my doubts. Either way, I would have to confess to her what I believed.

By the thirteenth century, overland pilgrimage routes to the Holy Land became too dangerous even for groups. Fortunately for the city’s coffers, Venetian merchants, who controlled the Mediterranean Sea lanes and enjoyed friendly relations with Middle Eastern authorities, offered all-inclusive return-trip tours to the Holy Land. These pilgrimage package tours included food, accommodations, guided tours around the sacred sites, and sometimes even sightseeing stops in Egypt. Aggressive advertising and inflated promises complete the resemblance of these early pilgrim tours to the modern tourism industry.

Understandably, this professionalization of pilgrimage caused anxiety among the more spiritually minded. A fifteenth-century pilgrim named Santo Brasca lamented about his contemporaries merely doing it for the ’gram: “Let no man go to the Holy Land just to see the world. Or simply to boast ‘I have been there’ and ‘I have seen that’ and so win the admiration of his friends.”

What Santo Brasca couldn’t have known is that the heyday of pilgrimage was already drawing to a close. With its links to the cult of the saints, the veneration of images, the earning of merit, and the granting of indulgences, pilgrimage quickly became a prime target for the Protestant Reformers. Martin Luther quipped that “Enough pieces of the true cross exist in the monasteries of Europe to build an entire ship and enough thorns exist from Christ's crown to fill an entire forest.” In 1520, he declared, “All pilgrimages should be stopped. There is no good in them: no commandment enjoins them, no obedience attaches to them. Rather do these pilgrimages give countless occasions to commit sin and to despise God's commandments.” He suggested that emphasis on special “holy places” devalued other locations, such as the local parish church, where believers should also expect to encounter God, “who is the same God everywhere.”

Catholic leaders too began looking less favorably on pilgrimage. The Dutch Catholic reformer Erasmus mocked pilgrims who leave “for the sake of religion, [but] return home full of superstition” and loaded down with useless souvenirs and badges.

On a cool, March evening in 2010, I walked with Mariya across the National Mall and up the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. We found a quiet spot in the back of the monument, looking out across the Potomac. With terror that I was about to cause the destruction of our relationship, I confessed my two dark secrets. Doubt. Depression. Her answer was a miracle of grace. Our love will overcome all.

Mariya’s faith in me, in our future together, opened up for me a different interpretation of faith. In time, I began to understand faith less as a set of defined statements I could intellectually assent to, and more as a trusting relationship with the divine, an openness to transformation by spirit and love. I found myself returning more frequently to my memory of Chartres Cathedral. Eventually, I gained a word to describe my experience there: mystery. The beautiful and infinite mystery of Christ’s condescension.

Over the centuries, as the flow of pilgrims slowed, large chunks of the original Camino de Santiago route disappeared, reclaimed by forest growth and mountain slides. Journeys to Jerusalem and Rome also declined. Christian pilgrimage appeared to be dying.

But perhaps unexpectedly, in our time, pilgrimage has undergone a resurrection. In the early 1970s, only ten pilgrims were registered for the Camino. By 1985, the number had climbed to 700. From there it jumped to 5,000 in 1990, and to a staggering 350,000 in 2019.

Of course, this rapid resurgence has brought with it new challenges. There is a growing tension between traditionalist pilgrims, for whom the journey is spiritually inspired and who walk the entire distance, and those sometimes derisively referred to as “pseudo-pilgrims.” The latter often walk only the last one hundred kilometers (to qualify for the coveted certificate showing proof of having completed the Camino), usually without packs or walking sticks. Others go full tourist, who avoid the modest pilgrim accommodation in albergues (hostels), stay instead in hotels, and even arrange to have their luggage transported between hotels.

I find the conflict between pilgrims and tourists on the Camino fascinating because it causes me to examine my own soul. In my circuitous journey of faith, have I been a pilgrim or a tourist? How can I know? Perhaps the difference is that one of them takes on real risk. Journeys of the spirit may not involve threats from bandits or disease, but they certainly present a danger to our current selves: our self-image, our settled habits. The focus of pilgrimage is often on the destination but perhaps equally important is what we leave behind. As the theologian Wesley Granberg-Michaelson writes, “Religious faith is an embodied journey, not a protected cocoon of beliefs.” To become a pilgrim of the soul is to walk each day toward a horizon of transformation. It is to follow the marked—and sometimes unmarked—path away from what is merely comfortable or merely good enough, and towards a radically new kind of being. As I search myself, I know following that path is a constant challenge.

The good news of the gospel is that we don’t walk that path alone. Jesus declared that he is “the way, the truth, and the life.” The hope of every Christian pilgrim is to walk the way of Christ, and, as on the road to Emmaus, find ourselves, unexpectedly, side-by-side with the Lord. But to recognize him, we must develop hearts sensitive enough to burn in his presence and eyes perceptive enough to see his face in that of a stranger. The fruit of this spiritual cultivation is that we wayfarers in the wilderness might press upon the Savior to abide with us, breaking blessed bread at his table of everlasting life.

On that snowy December day in Chartres, in a place that had spiritually sustained me for so long, Mariya and I pledged to walk together always in faith and love. Standing side by side in the center of the labyrinth, we looked up at the great West Rose Window. It depicts scenes from the Last Judgment, with Jesus as righteous judge in the center surrounded by saints awaiting resurrection. At that moment, a ray of sunshine pierced the cloudy French sky, shimmered across the glass, and bathed us in color.

Zachary Davis is the Executive Director of Faith Matters and the Editor of Wayfare.

Chartres Cathedral Window Lithographies by Etienne Houvet.

Moving, informative, sacred, and "mysteriously" hopeful!

Thank you for this beautiful post! I loved how you wove your personal story of pilgrimage into the larger concept and history of pilgrimage. It made accessible and alluring.