Joining Wildernesses

Reflections on Joyful Discipleship

During the April 2024 general conference, Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf said, “We all know people who say… that they are happy enough without religion. I acknowledge and respect these feelings… We’re simply saying that God has something more to give. A higher and more profound joy” (emphasis added). Elder Uchtdorf adds his voice to that of other Latter-day Saints in proclaiming that being a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints brings a unique type of joy in their lives, distinct from the happiness experienced outside of Church contexts. From Eliza R. Snow, who taught, “None but saints can be happy under every circumstance,”1 to Elder Patrick Kearon’s October 2024 address, “Welcome to the Church of Joy.” President Russell M. Nelson has emphasized this teaching on numerous occasions, teaching that “Joy is a gift for the faithful. It is the gift that comes from intentionally trying to live a righteous life, as taught by Jesus Christ.”

Growing up, when I read scriptures and listened to talks like these, I would imagine my life as if it were a scale, with one side labeled “happy” and the other side labeled “sad.” It didn’t matter how many things were on the sad side; if “membership in the Church” was on the happy side, even if it were the only thing on the happy side, the scale would always tip toward happiness, and I would feel unburdened even in hardship. In this way, I felt that the Church was like a cocoon, functioning as a complete shield, offering no space for anything uncomfortable or sad to tip the scale of life toward sadness. That’s what I believed the “church of joy” would do for me.

However, that picturesque outcome hasn’t played out in my life. Despite my lifelong active involvement in church, I haven’t always felt that being a member of the Church or having a testimony of its teachings canceled out all of the sorrow in my life as I believed it would. And since that belief is widely held among Latter-day Saints, that same disillusionment must also be widely felt. Little wonder then that the repeated teaching that the Church is a “church of joy” rings hollow to some and insulting to many others. Thinking that the Church is supposed to make us happy has led to a lot of pain, confusion, and sadly contentious discourse between current and former Church members. I know and love many former Church members who would not describe their experience in the Church as joyful. In fact, most would say, as Elder Uchtdorf pointed out, that their life now is more joyful than it ever was within the Church. Some feel scammed because Church membership was insufficient to tip their scale toward happiness when the weight on the sad side increased to unbearable amounts. Still others feel that Church membership never really was on the happy side of their scale. In her book Sacred Struggle, Melissa Inouye references a few examples of such people. “[The Church] wasn’t a place of refuge for [my friend] Jeffrey . . . who was gay, who felt that he had to conceal his sexual orientation at church. It wasn’t a safe place for my friends who were black, whose Sunday school teachers told them that because of the amount of melanin they had in their skin, they were cursed, [and] whose fellow saints called them foul words at church activities. It wasn’t a place of refuge for children and women who had been sexually abused by men entrusted with positions of ecclesiastical authority and stewardship.” When God declares the Church to be “a refuge from the storm” (Doctrine and Covenants 115:6), it can be disheartening and perplexing to experience or witness deep suffering within it.

I feel great pain at the hurt others have experienced in church and have felt similar confusion and disappointment when the Church hasn’t tipped the scale how I’d hoped and believed it would. But what if God never intended for the Church to tip the scale toward happiness all the time? In fact, what if sorrow being “swallowed up in the joy of Christ” (Alma 31:38) doesn’t mean it disappears or cancels out but instead changes shape in our consciousness? Perhaps what is needed is an alternate interpretation of the term “joy of the gospel,” one that leaves room for sorrow and joy to be felt simultaneously and affirms scriptural and prophetic teachings while providing a healthier alternative to the cultural assumptions that have led to so much confusion, judgment, and lack of understanding between current and former Church members.

Joining with the Terrible

In the April 2024 general conference address I mentioned earlier, I find it interesting that Elder Uchtdorf seems to draw a semantic distinction between “beautiful, wholesome pleasures and delights” and “a higher and more profound joy.” If this distinction was intentional, then Elder Uchtdorf is adding his voice to a growing number who believe that joy as an emotion is something distinct and more profound than mere pleasure and delight. “A lot of people seem to feel that joy is only the most intense version of pleasure,” wrote the English novelist Zadie Smith, “arrived at by the same road—you simply have to go a little further down the track. That has not been my experience.” Therein lies a possible source of misunderstanding. As Zadie Smith highlights, most people use the words “joy” and “happiness” synonymously, despite there being a general sense of their distinctness. Former and current members of the Church may be feeling lied to when their participation in the Church is not bringing them happiness, when in fact the goal of church participation is actually joy, which according to Zadie Smith, “has very little pleasure in it.”

If we accept that joy is different from pleasure, then what is joy, and how is it different? Writer and professor Ross Gay offers one intriguing idea. He posits that joy is born by way of “an entering and a joining with the terrible.” He elaborates on this idea by recounting an occasion when a student of his described her ideal classroom environment in the following way: “What if we joined our wildernesses together?” Gay muses on this, saying, “Every person I get to know . . . lives with some profound personal sorrow. Brother addicted. Mother murdered. Dad died in surgery. Rejected by their family. Cancer came back. Evicted. Fetus not okay. Everyone, regardless, always, of everything.” He continues, “Is this, sorrow . . . the great wilderness? Is sorrow the true wild? And if it is—and if we join them—your wild to mine—what’s that? . . . What if that is joy?” I can’t help but love this idea: What if joy is what results when we join our wilderness to others’ wilderness, or rather, our sorrow to others’ sorrow? Does this not sound like Lehi’s teaching that we can have “no joy, [if we know] no misery” (2 Nephi 2:23), or Elder Uchtdorf’s teaching that “joy and sorrow are inseparable companions”? What if the substance of joy is not pleasure and delight but a community’s combined sorrows?

If that’s the case, then doesn’t this type of joy sound more like the life Jesus lived? President Nelson taught that “Jesus Christ is joy!” Yet Isaiah called him, “a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief” (Isaiah 53:3). What if the fact that Christ “hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows” (Isaiah 53:4) is the very reason that he epitomizes joy? Perhaps, then, to say that the gospel brings joy doesn’t mean, as I once believed, that it acts as a cocoon, nor does it mean that the gospel will always tip our scales toward happiness over sorrow. Maybe a joyful life isn’t a life unfazed by hardship but a life of embracing hardship, or, as Elder Uchtdorf teaches, a life “of yoke-bearing and burden-lifting.”

Joy and The Work of Connecting

If joy is characterized not by pleasure but by a willingness to take on sorrow, then why should we want it? What is there to gain from conjoining sorrows with others? If discipleship is concerned with joy but joy isn’t as easily obtained as I once thought, then why should I stay? I think the answer lies in what joy brings into our lives that mere happiness or pleasure cannot. Indian psychologist Girishwar Misra is well-known for his framework positing that emotions exist between individuals, not within individuals. I think this conceptualization beautifully illustrates how joy feels different than happiness. Joy is so rich because it is a shared experience, not an internal sensation. American psychologist Brené Brown reveals a similar sentiment in her book Atlas of the Heart, in which she conceptualizes joy as “an intense feeling of deep spiritual connection.” When we allow others into our wilderness, letting them become familiar with our sorrow and in turn becoming familiar with theirs, we find a connectedness capable of truly diminishing loneliness. If one is seeking happiness in life, then one might find success from seeking out personal and individual fulfillment and sensations. However, a joyful life is one characterized by the seeking out of relationships and connectedness, not individual pleasure.

That is why the joining of wildernesses, though hard work, results in deep joy. When we get to truly know a person in all of their flaws, becoming acquainted with and connecting to their life’s sorrows, the connection and spiritual siblinghood that we feel with that person is incredible! It’s richer and more awe-inspiring than any kind of pleasure. While pleasurable experiences change our state of being in the moment, joyful experiences transform us. When we connect with others’ sorrows on a deep spiritual level, our view of the world is changed. Having entered into the wilderness of another person, our wildernesses take on a different shape. One could say that our wildernesses become “swallowed up in . . . joy” (Alma 31:38) when they are combined. The call to be a joyful disciple is a call to prioritize connection over personal satisfaction because connection is truly what makes life worth living.

This feeling of transformative joy is something that I have experienced many times through my Church experience. I felt it when I visited and administered the sacrament to elderly members of my ward as a priest. I felt it while attending church during the COVID-19 pandemic, looking at those in my YSA congregation not wearing face masks and taking a break from judging them to instead imagine what kinds of fears and struggles they may be bringing to church to be healed by Jesus. I felt it as a ministering brother giving a blessing to a ward member struggling with addiction. I’ve felt it as I’ve prayed for others, read scriptures, learned about thorny episodes in Church history, and listened to the stories and struggles of marginalized members and former members. Each of these experiences transformed me in profound ways. These moments, alongside moments of deep frustration and pain associated with my church worship, have truly made my discipleship worthwhile.

Conclusion

In his book Letters to a Young Mormon, Adam Miller powerfully writes, “Mormonism is a way of living rather than dodging life.” Humans naturally do a lot of things to dodge life. We choose, for various reasons, to ignore life and engage in numbing activities rather than live fully. Alcohol, drugs, pornography, yelling at people on social media, and streaming hours of television are primarily ways of escaping the pain of life. For many, I think religious beliefs fill that same function. Belief in an afterlife, the power of prayer, and the existence of divinely led prophets can be mentally configured as divine means that allow them to bypass life’s discomfort. The idea that the Church is a “church of joy” may very well serve that purpose for some people.

I truly believe that membership within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is at its best and most joyful when it encourages us to live life instead of dodge it. Ultimately, I think God is trying to show us that trying to find peace by striving to eliminate sorrow results in its own kind of spiritual exhaustion. God doesn’t want us to burn ourselves out by tirelessly trying to escape our wilderness, believing that effort to be the essence of a gospel life. Instead, He wants us to feel the deeper, more profound joy of exploring our wilderness and that of others. He sent his Son “that [we] might have life, and that [we] might have it more abundantly” (John 10:10). Having abundant life means having it all, sorrow and wilderness included. But even as God points us away from the increasingly popular yet ultimately hollow promise of dodging life and escaping the wilderness, he shows us that life is lived abundantly when it is lived in joy. And joy is achieved when we lose ourselves in the work of joining wildernesses.

Latter-day Saints do not have a monopoly on joy, but I believe membership in the Church affords us unique opportunities to step into the wildernesses of people we would otherwise ignore, exchanging the ideas we may have formed about them for the reality we connect to when we look into their faces and embrace our common woundedness. I don’t know that living the gospel has made me happier. In fact, in a lot of ways, it hasn’t. But I am certain that it has filled my life with greater connectedness with a greater variety of people. I feel it has given me “a higher and more profound joy.”

Travis Hicks is a doctoral student studying developmental psychology in Louisville, KY. He is a lifelong member of the church with a deep curiosity about the frameworks we apply to our faith.

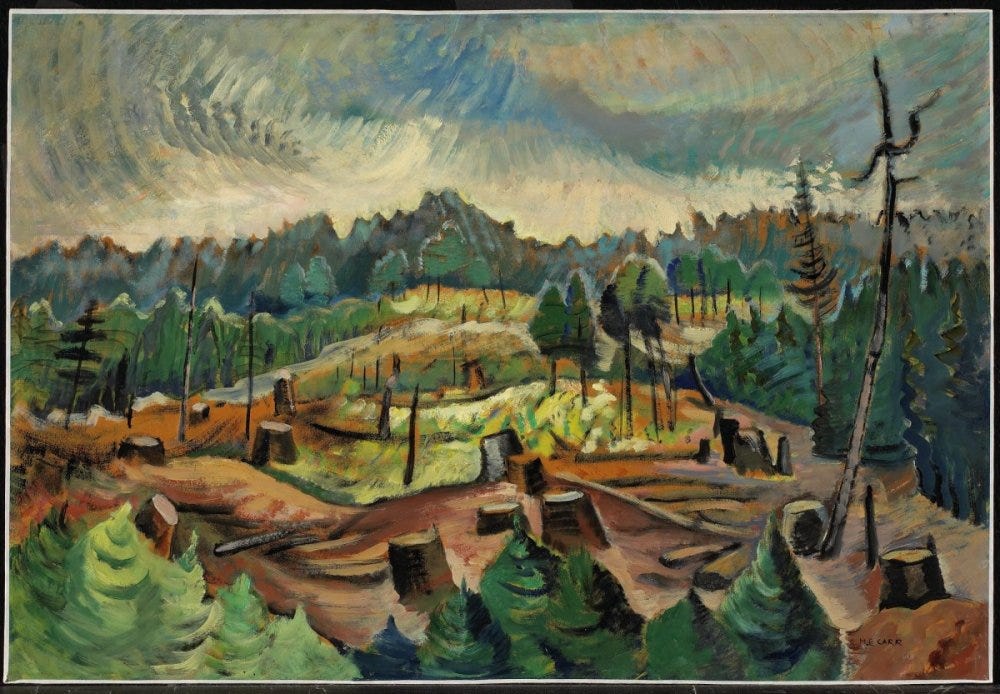

Art by Emily Carr (1871-1945).

Edward W. Tullidge, The Women of Mormondom (1877), 145–46.

Really good. Thank you for tackling these ideas head-on.