A Zen parable tells of a professor who travels to Japan to learn about Zen. As soon as he arrives at the nearest monastery, however, he sits in front of the Zen master and waxes on and on about all he’d already learned of Zen through books.

After hearing this professor pontificate at length, the Zen master sets a full cup of tea in front of him. Then he begins to pour tea into it. He keeps pouring, as tea flows across the table and splashes onto the floor.

“Stop pouring!” the professor says. “You’re spilling tea everywhere.”

With that, the Zen master stops. He looks in the professor’s eyes and says, “Like this cup of tea, you are already full. How can I show you what Zen is unless you first empty your cup?”

It’s a story with a universal message, which is that when we’re too certain that we already know everything, we cannot learn. We cannot grow.

A similar message is embedded in my own Latter-day Saint heritage. The Book of Mormon warns against “the vainness, and the frailties, and the foolishness of men,” saying that “when they are learned they think they are wise, and hearken not unto the counsel of God, for they set it aside, supposing they know of themselves” (2 Ne. 9:28). In a similar vein, other voices in the book declare, “I do not know the meaning of all things” (1 Ne. 11:17) and “I do not know all things” (Words of Mormon 1:7) and “as to this thing I do not know” (Alma 7:8).

It could even be said that the entire Latter-day Saint tradition grew from a place of not knowing. As a teenager, Joseph Smith was so confused about religious questions that he later wrote, “How to act I did not know, and unless I could get more wisdom than I then had, I would never know” (JS–H 1:12). From that not-knowing, the story goes, he was open to receive wisdom.

And yet, in my experience, a phrase like “I do not know” often seems out of place in the tradition today, like it no longer has value in Latter-day Saint life. This is perhaps most clear when members gather once a month for fast and testimony meeting to name what they do know—“I know this Church is true,” “I know we’re led by a prophet of God,” “I know Christ lives,” and so on.

These “I know” statements produce wonderful fruits—including a strong sense of unity, belonging, purpose, and identity.

They do all of these things, that is, until they don’t.

As I’ve written about elsewhere, around fifteen years ago I experienced a faith crisis brought on by discovering that the version of Latter-day Saint and biblical history my culture had handed to me as a child didn’t match with what was conveyed in many scholarly sources on the topics.

This discovery wasn’t a matter of acquiring benign but fascinating tidbits about my tradition. Rather, I experienced a dramatic shift with real-world effects on my sense of belonging in my Latter-day Saint community. I suddenly felt like a foreigner in my homeland, especially during testimony meetings. If all I had to offer was “I do not know,” how could I belong in an organization that seemed so saturated in knowing?

It was a terribly isolating stretch of time. I kept up my Mormon habits out of a love for the tradition—the way it tied me to my ancestry, the weekly conversations about timeless values, the hymns I’d sung since childhood, etc.—but my actions soon felt zombie-like, disconnected from head and heart. Occasionally, I spoke up about my doubts at church in an effort to be heard and to even “correct” other members. But that never felt right. So I mostly stayed silent.

To see if I could rekindle a sense of camaraderie and belonging, I started attending post-Mormon gatherings. I met many wonderful people there, as I had in the LDS Church, but the recurring topics of conversation—focused, as they were, against something rather than for something—never really lit anything in me. I didn’t feel like I could fully come alive in those spaces, as much as I appreciated being seen in my unorthodox views.

Then, more than a decade ago, I stumbled into a six-week mindfulness course facilitated by Thomas McConkie at the Lower Lights School of Wisdom. Here was an in-person community that brought together a range of participants—those who were active in Mormonism, those who had left the tradition, and those who had never been part of it. Belief wasn’t at the forefront, wasn’t a point of contention one way or the other. Rather, Lower Lights was a place to attune to something deeper together, to explore a way of living centered less in claims and propositions and more in a sense of divine trust. Week after week, I noticed something lighting in me. I felt a spark of life, enough to return for the next Lower Lights event, and the next and the next.

I’ve felt this same spark of life—this experience with the divine—several times since finding Lower Lights, including at the launch party for the first physical issue of this magazine, Wayfare. I had been following the rise of Wayfare closely, but I’d hesitated to get involved because I had (and admittedly still have) such complicated feelings about my Latter-day Saint heritage. And yet I felt something undeniably alive at that launch party, which was full of earnest, cheerful, and thoughtful people. It was more than “good party vibes.” I felt a resonance deep in my core, a sense of direction in the dark, an alignment with God, a desire to contribute and build.

I hesitate to limit any of these and other similar experiences I’ve had in the last decade by confining them to a single label, but if I had to, I might say that they all had a hint of the mystical. These experiences softened my heart and opened my mind toward all people and communities that are trying—however clumsily, as we all are—to draw nearer to truth. As meditation teacher Shinzen Young writes, “Once you begin to have mystical experiences, you can feel right at home in anybody’s church.” Given this, these experiences at Lower Lights and Wayfare have led me into fuller participation in my local congregation, where I currently teach the men once a month in elders quorum. I no longer harbor my prior inclinations of trying to “correct” other Latter-day Saints like I once did. I’m just trying to keep the space alive, staying soft and open to the possibility of being surprised by a God I do not fully understand.

Above all, I’ve slowly been able to attune to a sense of deep trust in life itself, intuiting that even while I don’t have the same convictions about certain claims and propositions that I once did, I can trust that which sparks a sense of life in me. I don’t know what that ultimately means, or where it will take me. And I certainly wouldn’t presume to say that I’ve found the true communities for all people everywhere. I just have a felt sense that these communities have offered me belonging and aliveness in connection to my heritage.

In the words of the hymn “Lead Kindly Light:”

I do not ask to see the distant scene; one step enough for me.

To return to the Zen story I started with, I’m beginning to see that growth happens when we “drink in” our current understanding of life’s mysteries and then hold our empty cup out, open for more. It’s less a matter of belief and more a matter of trust—of faith. We must trust that even though it’s unsettling to hold out an empty cup that cannot be filled on our own timetable, this is how we grow.

Faith willingly drinks in and holds out the empty cup.

Jon Ogden is the cofounder of Uplift Kids, which helps families explore wisdom and timeless values together. To subscribe to his column, first subscribe to Wayfare, then click here to manage your subscription and turn on notifications for “One Step Enough.”

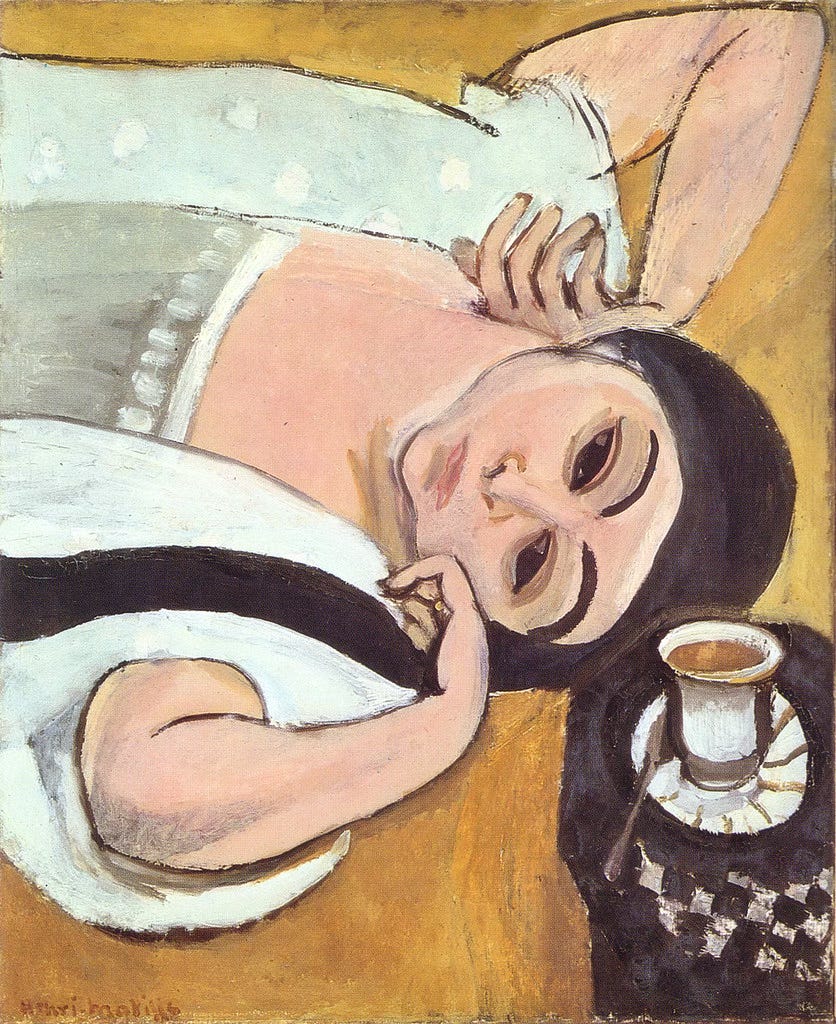

Art by Henri Matisse (1869–1954).

This speaks to me so much. Your statement "the recurring topics of conversation—focused, as they were, against something rather than for something—never really lit anything in me." finally put into simple words for me the driving force in my heart. Thank you!!

I resonate with this. Sip, chug, pour some out—but always leave room

for what’s not yet known. Thanks for writing and sharing, Jon!!