Wayfare is pleased to introduce a new column by Jon Ogden, Senior Editor at the magazine and a beautiful thinker. To subscribe to his column, first subscribe to Wayfare, then click here to manage your subscription and turn on notifications for One Step Enough.

In his book My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer, the poet Christian Wiman tells the story of his evolving faith. He grew up evangelical Christian and had a powerful spiritual experience at church as a twelve-year-old, only to later reject his tradition and become an “ambivalent atheist” in college.

Then, when he was nearly forty, he fell in love and got married. The experience renewed a sense of divine love in him. “I don’t think the human love preceded the divine love, exactly,” he writes. “But it was human love that reawakened divine love.” Out of this love, he and his spouse started praying together—“spontaneously,” Wiman writes, “though we’d been away from any sort of organized religion for years.” He felt what he called an “assent to a faith that had long been latent within me.”

Tragically, less than a year after he got married, he was diagnosed with a rare and incurable form of cancer. That’s when he was drawn to belong to a church community again. As he tells it, “My wife and I found ourselves—and that’s just what it felt like, that suggestion of passivity and chance—walking through the doors of the little church at the end of our block. I’d passed right by the church every day for three years on my way to the train and work downtown, but I couldn’t even have told you what denomination it was. I wasn’t tuned in to churches. Or to Christianity. I was, however, tuned in to something.”

It took time and genuine wrestling—often in the form of frank debates with the church’s preacher—for Wiman to settle into church life again, but he did. “I needed a form for the faith,” he says, “the inchoate faith that I was already feeling.”

A form for the faith.

Christian Wiman’s story of returning to a religious form isn’t an isolated event. As a report from the Wheatley Institute reveals, roughly 1 in 5 people who have stepped away from religion eventually return to it.

The report explores why these “reconversions” happen and finds that—just as in Christian Wiman’s story—the experience is often tied both to love (human and divine) and to life circumstances (e.g., a marriage, a diagnosis, or a new child). One study cited in the report says that those who returned were those who had experienced “love, respect, and patience” instead of judgment for having taken “a different path.” Another study found that “in almost every narrative, the reconversion process focuses on a new or rekindled relationship with God.” And another study revealed that this “reconnection with God came through intimate, individualized, and spiritual experiences.” This intimacy and individuality is key, since, according to that same study, “none of our participants mentioned specific resources produced by religious organizations as foundational to the resolution of their faith crisis.”

In short, these reconversions didn’t happen through calculated means—through apologetic efforts from a sanctioned church source. They didn’t happen because someone encountered a logical argument or an official church talk that brought them back. They happened because love worked its way.

What does this mean for those who long for someone to return to religion?

The answer is both simple and complicated.

In its simple form, the answer is the same for everyone, regardless of religious affiliation or disaffiliation: The answer is love. As the Carmelite nun Teresa of Ávila wrote, the spiritual path consists of two parts: loving God and loving each other. And how do we know we are on this path? “The most reliable sign that we are following both of these teachings,” writes Teresa, “is that we are loving each other.” That’s the path. No one’s above it.

But the path is complicated because the outcome of our love cannot be predetermined. Sometimes we love and the other person never returns to the fold. Sometimes we love and we are changed. And sometimes we love and the person returns to religion, but not in the way we may have envisioned.

“[Love] does not insist on its own way,” writes the apostle Paul.

Similarly, Joseph Smith says, “If I esteem mankind to be in error shall I bear them down? No! I will lift them up, and in his own way if I cannot persuade him my way is better! I will ask no man to believe as I do.”

This is wise advice both for those who stay in religion and for those who leave. In either case, love is eclipsed when there’s an inflexible demand to adhere only to our pre-scripted outcome—a demand that results in misery. As the Bhagavad Gita says, “Those who are motivated only by desire for the fruits of their action are miserable, for they are constantly anxious about the results of what they do.”

Love, by contrast, “casts out fear” and replaces it with trust. It holds faith that whatever the fruits of love will be, they will be better than what we demand must happen.

Of course, none of this means that we must erase ourselves, deny our individual desires, or accept cruelty from anyone. Love requires self-respect, which entails not only hearing what the other person wants but also stating what we want in a relationship. Without self-respect, it’s not love.

Nor does any of this mean that differences of beliefs don’t come with an immense price tag or an almost unbearable grief. Anyone whose family has been disrupted by differences of belief knows the potential aftermath—traditions upended, future plans unraveled, certain values up for grabs. In my Latter-day Saint tradition, this rupture can lead to deep worries about whether kids and grandkids will fall to substance abuse, whether a spouse will break marriage vows, whether traditions like prayer or going to church together are now off the table, and much more. A shift in belief can carry effects that disrupt daily life and ripple for decades.

In times of grief, it can help to realize just how universal this story is—and how many times it’s happened throughout history. None of us are alone in the pain that stems from disagreements about belief, whether we stay in or leave a religion.

To give just one example: One of my ancestors named Charles Layton was born in Bedfordshire, England in 1832 to Bathsheba Layton and an unknown father. When he was a teenager, Charles and two of his friends decided one night that they were going to disrupt a sermon by some Latter-day Saint missionaries, but were instead so moved by the missionaries’ sermon that they converted and got baptized. Two years later, at the age of eighteen, Charles left his family and took the seven-week voyage from England to New Orleans before making his way to join the Latter-day Saints in Utah.

Bathsheba never saw Charles again. “My dear son,” she wrote in an 1864 letter, “you do not say anything about coming home to see us. We should all like to see you very much.” She continued, “You say you wanted to know whether your sisters remember you.” (She doesn’t say whether they do, implying that no, they don’t.) “Now you wanted to know whether they would join the Mormons. They said they think they never shall.”

In the letter, I sense pain that stemmed from a disagreement about belief, perhaps compounded by the fact that Charles had already taken a second wife by that point. It makes me think of what life was like even earlier in my family history when the Romans forced my Celtic ancestors to convert to Christianity, which almost certainly disrupted familial ties as well.

In each case, my ancestors likely felt a sense of searing pain and an inevitable acceptance of the powerlessness we all feel because we cannot control the beliefs or actions of those who are close to us.

What can we do in light of this pain and powerlessness?

We can choose to stay soft, open, and humble to the possibility that we might have something to gain from people whose beliefs differ from our own. That’s love. It’s what Jesus pointed to in the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector, which he directed to those “who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt.” In the parable, a Pharisee thanks God that he is “not like other people” while the tax collector bows his head to God and pleads for mercy. The Pharisee is closed off and full of contempt. The tax collector is open and, presumably, full of love.

Love shifts us away from an insistence that we alone are righteous (and therefore always deserve to get our way) toward a realization that there are new paths that can only be discovered through our encounters with each other. In this sense, love integrates each of our gifts into a new way of being together.

On this note, I think again of Christian Wiman, whose return to religion wasn’t a flat retreading of his fundamentalist evangelical upbringing (likely to the disappointment of some of his friends and family). Neither did his return to religion stem from a complete buy-in of the propositional truth claims taught in the church that sat a block away from his house. Rather, Wiman integrated the hard-earned intellectual gifts from his years as an atheist alongside a surprising discovery that in order to grow in community, faith has to take some form.

And yet even here Wiman is open to many possibilities. While he sympathizes with the view that your native religion might have “such a bone-deep hold on you that, as with a native language, it’s your only hope for true religious fluency,” he doesn’t insist that this view is an incontrovertible truth—that it’s the one true form that faith can take. “I have friends whose patchwork religious lives have a hard-earned authenticity to them,” he writes. In other words, for Wiman, there’s always an underlying sense of trust, not so much in the specific outcome, but instead in the transformative discipline of love itself.

It’s terribly difficult to have faith in all of this—to stay soft and open and strong at an individual and cultural level. But it is the best hope for all people, including those of us in the broader Latter-day Saint context. As Joseph Smith said, “In reality and essence we do not differ so far in our religious views but that we could all drink into one principle of love.”

Do we have the faith to drink into this one principle of love? Can we develop the capacity to trust—whether we consider ourselves “in” or “out” of religion—that whatever emerges through love will be fruit worth tasting?

Jon Ogden is Co-Founder at UpliftKids.org, which helps families explore wisdom and timeless values together. He envisions a future that transcends the worst of the past and includes the best. Subscribe to his column by clicking here to manage notifications and select One Step Enough.

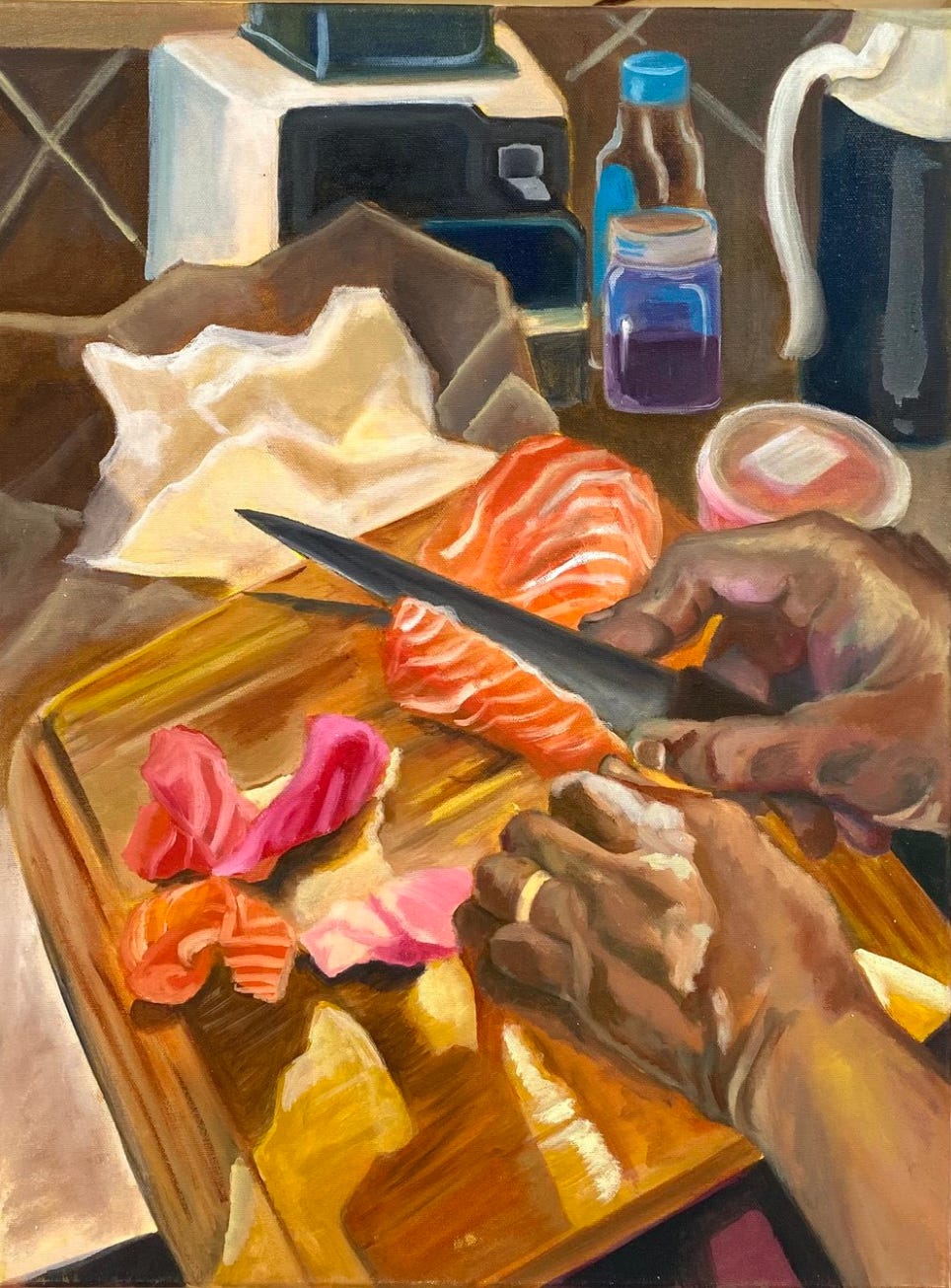

Art by Amanda Yim.

Fantastic work Jon. When Jesus tells his apostles “I am the way, the truth and the light …” I believe this is what he was referring to. God is love. Want to find your way to God? Love is the way and Jesus was embodiment of that idea.

I enjoyed this article very much Thank you. But I especially enjoyed your recent essay in Wayfare magazine summer 2025 that I just received entitled "An End to Enmity". As well as the artwork by Anna M. Wright. Oh, and that you quoted Russian author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.