Holy Gestures

Two Stories and a Poem

On Unicorns

On a Sunday like any other, I am scrambling after church to corral the littlest before she escapes from her class to run down the hall and through the chapel, which is usually occupied by penitents from the other ward. This of course means there is no post-meeting chit-chat, the kind my own mother would engage in for what seemed hours after church, prolonging our hunger and our scheduled date with the long hours of Sabbath boredom, during which, in true extrovert fashion, she would make one long phone call after another, the way a chain smoker lights his next cigarette from the butt of the last. My children, however, ended up with a mother who is all task, who wants only to finish the business of going and coming, of feeding, to seek the quiet hour in which they are temporarily occupied, and she can turn to her thoughts.

So when we’ve finally clattered and belted into the van and I’ve shifted to reverse, my ten-year-old daughter blurts out,

“Mommy, I found a unicorn in the Bible! It’s in the scriptures! So I think they’re actually real!”

I look back to see her bright eyes, her smile, her whole countenance shining with joy at this thought: white glitter-bodied horse, muscled with brilliance, its mane a rainbow, a whole spectrum of light shining from each shaft, the single swirling cone a bright pillar reaching up to the heavens with an angelic chorus harmonizing Yes, Virginia, there is a unicorn!

Moments later, when she breaks down in tears, I realize—No, the right choice at that moment was not to point her to the footnote of Isaiah 34:7, which reads, “RE’EM, a wild ox,” sending a ripple of disappointment through her, as if her body has missed one step descending a staircase. She buckles in a little grief, bursting out an angry, “How do I know what to believe?!” She weeps at the trick words have played on her, at the loss of temporary hope—that the muscled density of animals could be corseted in a horse’s lines like calligraphy, glowing with its own light—but also at me. That in my need to teach, to correct, to point out truth and error—perhaps a tendency to live up to the smartest version of myself, rather than the kindest—I have taken the shine from her, put a kibosh on her naïveté, shut down the possibility of some future showdown of shame in which she discovers before her peers that she has been misled. I have ripped off the bandaid and found skin attached. Did I think to praise the real intent she brought to scripture? Did I consider the joy of the moment her heart leapt within her to see the word in print, the word of God, the proof, the incredulity—ten years old, and I’m just now discovering this? The excitement that carried her through the end of her class, that she kept like a pearl to show her mother and say, Look what I found!

I put the car back in park. The other two kids meanwhile have begun squabbling over Primary candy rights. So naturally I have to settle that dispute by digging through the random paraphernalia in my purse: Batman mask, sunscreen, garage door opener (so that’s why the door keeps opening at random times!), fifty receipts, tampon wiggled free of its wrapper in the melee (I am lacking only an umbrella and coat rack!)—aha! One tender mercy, a Dove chocolate relic of a past Relief Society meeting—Here son, all is now right with the world.

Turning back to my daughter, I pass her a tissue, summon all my sympathies, and suggest (like I should have in the first place!) that when we get home, we’ll look at the reference together and look up some things to answer her questions. This seems to appease her enough that I can get us home.

Later, when we Google “unicorns in the Bible,” one of the first links is an LDS Living article, only five years old, detailing unicorn references in the KJV, and what the alternate translations indicate. (I’m imagining a similar fraught scenario that might have prompted this author to write the article.) We read:

that God “hears the strength of a RE’EM” (Numbers 23:22)

that he hears us “from the horns of RE’EM”— (Psalm 22:21)

that he “breaketh the cedars of Lebanon” and “maketh them to skip like a calf [. . .] like a young RE’EM”— (Psalm 29:5-6)

that he “exalts” our voices “like the horn of a RE’EM” and “anoints “ us— (Psalm 92:9-10)

What seems to pacify my daughter the most is the way the author kindly leaves room for speculation about the possible existence of some extinct creature that might have more closely resembled what my daughter envisioned (something from the Gospel of Lisa Frank). That a lack of evidence is not evidence of lack. That there is room for belief even in the face of what we circumscribe as fact, and once again, she has opened up to possibility, to her desires, to the idea that she can believe in the qualities of something, rather than requiring her idea of it to exist. That despite the thousands of years and shortcomings of language, some creature existed so mythic and powerful it captured the imagination of those psalmists, to compare to the power of Almighty God—something that had the strength of myth, something wild and unharnessed, something uncircumscribable; that its horns were a wild vehicle of prayer and desperation, a relic of what is unknowable about God, what is just out of reach, yet somehow reaches to us; that God’s voice both breaks the cedars in us and grants us the joy of wild things, a joy we cannot yet comprehend; that he can raise even our voices to that of myth, in a way which sanctifies us—Daughter, who could refuse to exult over this?!

But by now, her expression of curiosity and angst has waned to mere tolerance. Her eyes wander, distracted. That one magic moment when my child has opened herself to knowledge has closed like a snack cabinet. She’s ready to go. She’s ready to eat. She’s ready to go find other ways to entertain herself, which she hopefully won’t describe in years to come as “hours of Sabbath boredom.” And I am the one changed. Captive to my thoughts. Pondering the weak links in the chain of this poor and marvelous medium of language.

What the Wind Says

There are days we live as if death were nowhere in the background.—Li Young Lee

Sunday afternoon, the last day of April, my kids are watching scripture videos. Outside, the wind is tussling in the trees, the sun slanting to create a pool of shade, a clovered glade in our sloping backyard, and I decide: Kids, dinner tonight is a picnic.

We carry blankets down to the lawn and spread our snacks and sandwiches, listen to the ocean roar of the roiling branches towering over our yard, a great nunnery of trees hymning over us. The children share their strawberries with the bunnies, who fight over the tops, then pause to lick the juice from their paws, tracing halos over their heads.

We take a walk, and discover in the thick brambles of white flowers, not yet blackberries, growing over the fence, that honeysuckle has taken root and twined its way through the white bower, likely sprouted there from the vine I once dragged two blocks home, leaving my son, age three, to cry in the street, refusing to ride his tricycle, angry he was asked to do a hard thing.

The kids chase each other through the wide grassy yard, which just a year ago was a forest of dog fennel and brambles. They explored the back slope of forest just outside the fence, traipsing up to the road to skirt their way around the thick patch of thorns growing adjacent to the house.

They jump on the trampoline, their hair alive with electrons. Lydia, perceiving injury, gives herself over completely to the grief of being wronged by the world, throws her head back with a howl and lets loose all the demons competing within her for the last crumb of attention.

Her brother, meanwhile, smirks at the power he has to cause this apocalypse.

My eleven-year-old shows me her flips on the still rings, her dress collecting at her thighs, and I wonder how many more times she will feel this free before retreating into the cave of teenage angst.

My husband kisses the back of my neck.

What is the right word for the way the wind brings to the surface the inner turmoil of every silent thing, their incessant squirming, the way a child, age five, cannot hold still, must clap her hands and sing while I’m trying to brush her tiny gems of teeth?

Years ago, I came across the idea that the description of “the spirit of God” that “moved over” the waters in Genesis was an incomplete translation of the Hebrew. Ruach Elohim m’rechephet translates to “the spirit/breath/wind of God hovers.” But more than this: the “-phet” ending of the verb indicates that the subject—God—is female. Or as some interpret this—the part of God that is female. It is Her breath, Her wind that hovers. It is Her spirit that stirs in us, through us, carries with it our dissatisfaction, our need to escape, to wake us to what is alive in the blades of grass. That we too, created, are still full of life, making our Sabbath, again, delightful.

We discover the evidence of some giant rodent who has dug up an earthwork under our slide, the perfect shelter for his burrow, the hole a sign of what can any minute be lost to us—this present tense, this glorying in our bodies, in the natural world we ignore for the fraught internal one.

My daughter tells me they climbed the deer stand, felt the swaying of the wind and knew to descend, unsure of the tree’s ability to hold them, or how far it could bend without breaking.

Unspotted

What does it mean to keep something holy? Like I tell my five-year-old, don’t get that syrup in your hair? Might as well say don’t eat. Don’t play. Don’t live today, or you’ll get dirty. And aren’t all our hands grubby? What can you keep without killing it? When we found a snail on the drive, frozen and brought it in to warm, it thawed and swelled, each cell yawned and stretched slow as grass, its dank muscle like a tongue caught between desires—to lick, or articulate? If only one is holy, what are we here for? What is sacred without the body, what is devotion without it utterly offered up to what it was meant for? My daughter returns to me five times or more, for a kiss follows her kisses each time with a lick. To her, no animal body is unhuman, no gesture unholy if it is alive—how could I ever dare unlive her?

Elizabeth Garcia is a Georgia native and mother of three. Her debut collection, Resurrected Body, received Cider Press Review’s 2023 Editor’s Prize.

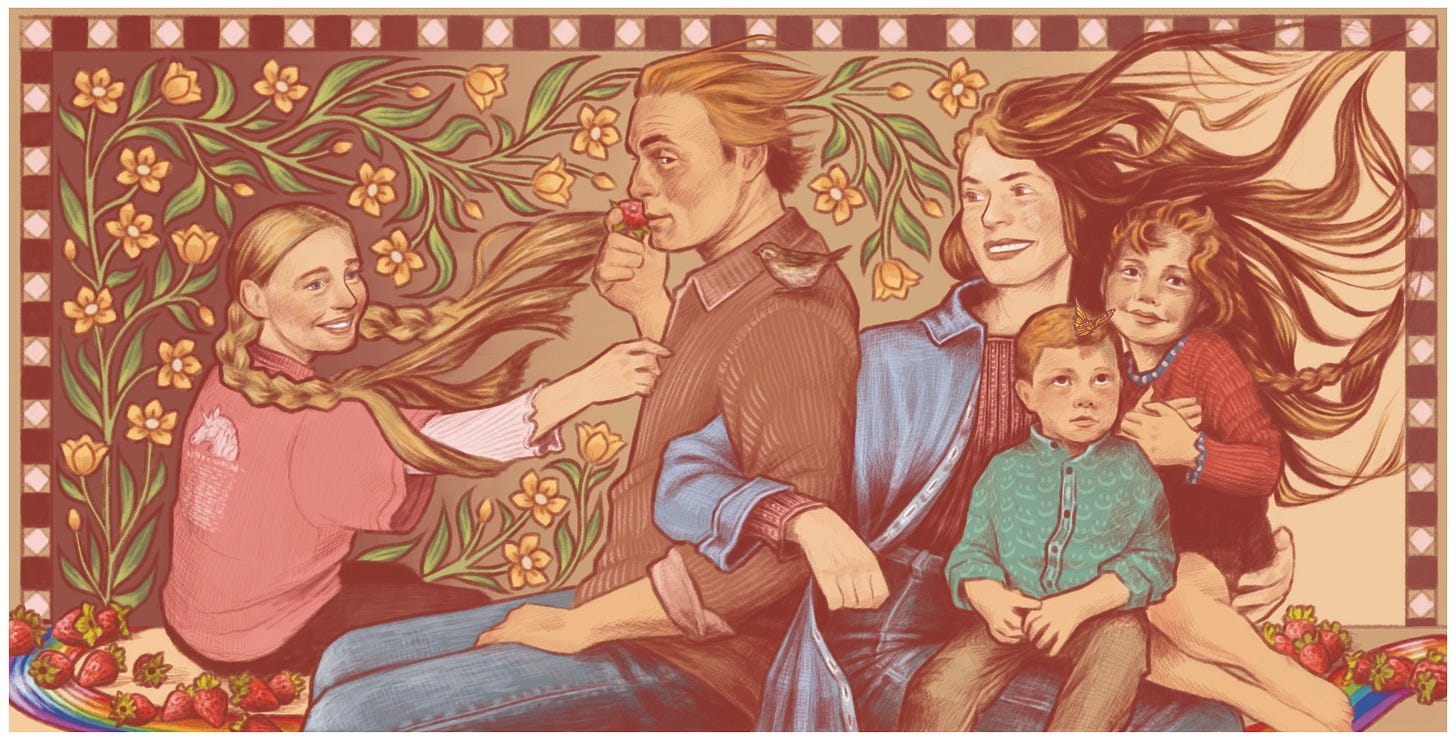

Art by Jessica Sarah Beach, @jessicabeach143, jessicasarahbeachart.com.

SAVE THE DATE

WAYFARE FESTIVAL 2025: WORLDS WITHOUT END

Join us in Park City on July 12, 2025 for a day of invigorating ideas and fresh friendships in a gorgeous setting. Gather with friends, artists, writers, and fellow wayfarers. It will be a feast for the soul. RSVP to come soon.

WAYFARE BOOK CLUB

KEEP READING

Seeing With Our Whole Bodies

Adapted from Seeing by Mason Kamana Allred, part of the Maxwell Institute’s Themes in the Doctrine and Covenants series. Find the original essay here.

Settling

You don’t notice it until the paint dries: the ceiling isn’t a crisp line. It’s hard to tell if the green stretches too high or the white reaches too low, but it’s off. It could be charming. It could be the imperfection that makes this all feel homey. More likely, it will be forgotten and slip into the background noise like the 1 p.m. train whistle.