Chapter One

The underworld, as seen in our diagram, is the region of the roots. We begin our journey descending into this place where life begins, into the underground where roots break free from seed and become the most permanent and stabilizing part of the tree. Roots withstand severe climatic conditions, storing sometimes millennia of experience. Incredibly, we are discovering that root tips function like brains, passing electric currents and storing important information.

Root systems take in water and nourishment in order to grow the tree, but they do nothing alone. Recent scientific research has opened our minds to the intricate workings of forest ecologies and the ways in which trees respond, communicate, and care for each other. Whole networks of organisms speak to each other, sending chemical signals below the ground. Roots call to fungi, to the root systems of surrounding trees, exchanging nourishment, information, and energy.

Just as intact root tips register changes—such as toxic substances, stones, and changes in soil—when roots are pruned, the “brain-like structures are cut off along with the sensitive tips.” This causes disorientation for the roots and interferes with the tree’s ability to sense direction underground. Its roots begin to grow only very shallowly, which keeps the tree from accessing needed water and nutrients.

We are discovering how the elder trees of the forest, the mother trees (the biggest, oldest trees with the most fungal connections, not necessarily females), are the keepers of wisdom. “When Mother Trees—the majestic hubs at the center of forest communication, protection, and sentience—die, they pass their wisdom to their kin, generation after generation, sharing the knowledge of what helps and what harms, who is friend or foe, and how to adapt and survive in an ever-changing landscape.” The older trees in the forest discern which neighboring saplings are their own kin. Mother trees connect with their young, conspecifics, and many surrounding species through their root systems, passing sugars and other nutrients.

In the gnarl of beetles and rot, in the communion of roots and fungi, we find powerful life forces, creatures who remind us of the ways in which death is woven into life in endless cycles. The work of the roots speaks to the hidden mysteries that unfold in the dark. They remind us that the dark is alive.

The underground plane symbolizes a place of spiritual growth and regeneration, of knowledge creation. Here, in this womb space, the unseen and obscured portions of both tree and soul reside. As we know from Alma 32 in the Book of Mormon, we must plant good seeds in good soil to expect our soultree to thrive and expand into eternal life. Here we are asked to evaluate the soil and how it has affected our roots. What beliefs, traditions of our fathers (from our literal ancestry and our cultural inheritance), and experiences may be keeping us from our full potential? What needs to be uprooted?

I like to think of the realm of the roots as the holding space for introspection and reevaluation of our true identities. A comprehension of this repository of hard-won wisdom and sustenance is necessary for our growth. As such, it demands everything from us, our full presence of mind, body, spirit, and heart. The darkness we encounter here asks us in quiet and measured ways to sit with it, to allow its slow workings to speak to the hidden, ineffable parts of us.

Many of us are afraid of the dark, but even more of us are afraid of being afraid. Mother God teaches us how to let our eyes adjust to the dim, and that the discomfort inherent in this common experience of the unknown encourages us to tend to our fears. So often, the darkness (the unknown, the unfamiliar, the unpleasant, the painful) is “the very next place where God is preparing to build [our] trust.” While fear exposes the limits of our present capacity, it also can be the perfect tool to reveal our potential capacity. During their own descent into the depths of Liberty Jail, Joseph Smith and his companions reflected on the necessity of soul-transforming experience, including a deep exploration of the shadows, as a prerequisite to leading another soul to the same path of radical growth: “Thy mind . . . if thou would lead a soul unto salvation, must stretch as high as the utmost Heavens, and search into and contemplate the lowest considerations of the darkest abyss, and expand upon the broad considerations of eternal expanse. Thou must commune with God.” We do this work not only for our own growth but also to prepare us to help others move toward transformation. Perhaps most poignantly, I have found that the feminine realm of the roots teaches us to face what we don’t understand, not with fear, hatred, or resentment but with acceptance, with the open heart of presence. It asks for a commitment to reinvention as we stare into the face of what is unresolved inside us.

This place of initiation can be extremely uncomfortable because of its uncertainties, unexpected pains, and the ways in which it will challenge some deeply held beliefs. The divinely feminine aspect of each of us calls for our perception of and devoted attention to the finer feelings, energies, and expressions of spirit woven throughout the living world, beckoning our souls to transgress beyond the edge of what we know so we may grow and create good fruit. It requires us to develop sovereignty—greater self-governing power and authority—before it allows us to progress on our spiritual journeys. We find the Mother waiting for us in this place of descent so that we may discover ourselves, and in doing so, begin to discover Her.

My life has taught me that deep feeling blooms deep knowing. And deep feeling requires deep listening. During my early teen years, I spent many hours sitting beneath my bedroom window watching the sky. The ceiling of my upstairs room sloped to a bench seat below a large skylight. As I sat, I could see out to the north face of Mount Olympus. I was particularly drawn to sit and watch on stormy days, during sunsets, at dusk, or under the slanting light of spring and autumn—times when the sky spoke of change. I was most aware of my own internal state at these times and felt my soul’s need to create. Some days I would read or write poetry as I watched. Others, I would listen to hours of music. I knew on some level that I needed that time to reconcile and weave together the reality of my life—its pain and disappointments as well as its joy—with the larger visions I had for myself and the world. My room became a sanctuary because I found myself there. The self that was revealed was a self deeply loved by God and deeply known. This direct connection to the divine oriented me during the most excruciating times of my life.

We believe that Jesus’s descent below all things, into pain and suffering, allowed Him to ascend above all things on His path to becoming our Savior. Like Jesus, we are called to descend into the shadows of our own souls, to face our internal wounds and unfinished parts so that we may also transform and expand toward greater light on our journeys of becoming. On the threshold of our journey, I would ask you to consider the context of the two great descents of Jesus on Earth—His earthly battlegrounds, if you will. The places that held Jesus through His atoning were the garden and the cross, an olive grove and a felled tree. Could it be that the Mother Tree was His support in His greatest need? What could this teach us about our own descents?

The Descent

The Creation Mother is always also the Death Mother and vice versa. Because of this dual nature, or double-tasking, the great work before us is to learn to understand what around and about us and what within us must live, and what must die.—Clarissa Pinkola Estés

As I turn inward, Mother asks me to question what matters. What if the cultural identifiers of merit by which I have perceived my worth were taken away, stripped from me as they were from Job? What of me remains? I attempt to see what is real, to follow the path of my heavenly parents and brother to do the work of reckoning and let die in me the things I think I ought to uproot in others. I try to tune into the emotional and intuitive landscapes of my soul and the more nuanced ways of relating to the world.

A profound inward listening allows for what is to be. Many times this looks like turning inward to face, admit to, and acknowledge pain. Tuning into our own pain (which so often includes the sorrow we feel watching those we love suffer), we allow it to fully express itself so that our hearts can experience it completely. In this state of vulnerability, our suffering is sanctified. Connections are made. Our chemical makeup alters, imprinted with expansive emotional landscapes. As poet Rainer Maria Rilke so beautifully described, in facing our shadow sides, we experience our “grief cries” as the mercy that defines our God and that allows us to be found in the abyss:

It’s possible I am pushing through solid rock in flintlike layers, as the ore lies, alone; I am such a long way in I see no way through, and no space: everything is close to my face, and everything close to my face is stone. I don’t have much knowledge yet in grief so this massive darkness makes me small. You be the master: make yourself fierce, break in: then your great transforming will happen to me, and my great grief cry will happen to you.

Christ’s suffering in the Garden of Gethsemane created a deep and resounding connection to divinity as well as to us. Our suffering can also connect us to each other and to our heavenly parents. Mother God holds us, as She did Her son Jesus, in the extremity of pain.

In the greatest paradox of mortal life, it is human nature to fear the most divine part of ourselves: our ability to heal, and in so doing, to metaphorically gain new life through new eyes. To grow in seership. Many times we wish instead, perhaps subconsciously, to turn to our own ignorance (Prov. 26:11), to suppress that which represents growth because it is the unknown. Because it will ask hard things of us and cause pain. Many times, this lack of demonstrated faith—this unwillingness to progress on our path of discipleship through healing—speaks to our perhaps unacknowledged resentment of the fundamental purpose of life, which is to change. We hold firm to our mindsets and to our known paradigms under the illusion of control. Little do we recognize, at first, that what we are ultimately saying is that at-one-ment is not something we really desire, that we prefer our comfortable gods, made in our own image. Our Mother, here in the dark, asks us to let go, to awaken and rouse our faculties. To feel all there is to feel.

I have felt the presence of the Mother in some of my most difficult descents. In the first trimester of my second pregnancy, I miscarried. A close friend came to offer comfort, and I found myself unable to speak about what had happened. I had no words. After she left, all I wanted was to be flat on my back on the earth. I laid down under the crab apple tree in my front yard. I felt my breathing slow and my body relax. I attended only to the presence of the tree: its undulating branches, red fruit, and peeling bark. As I held the moment in my soft gaze, the energy of its living form filled my knowing, and somehow I was found by the tree. I felt it aware of my presence, and in that mutual acknowledgment, a communion of some significant way. I was embraced in the tree’s knowing that everything was, and that was enough.

I saw my Mother in the tree, Her power to connect living souls above in the heavens to the mortal realm below, and in the tree’s composite of life and death. The upper canopy of this old crab apple comprised a gnarl of brittle black branches, a clear sign that the tree was dying. Yet its skirting branches were producing perhaps a double offering of fruit in what seemed to be an effort to make up for what the dead branches could no longer offer. This tree was giving everything to rebirth while surrendering to a slow decline. It embodied the endless cycle of life-death-life I had come to associate with the Mother and the same divine creative powers in me. The manifestation of God before me in the form of that tree was showing me how to be in the pain to find pain’s cure.

I felt raw about my struggles with my earthly mother as I grieved. While she did her best and cared for me in many ways, basic needs were left unmet during my childhood. As an adult, I carried the melancholy of emotional distance; I the realized I felt largely unmothered. Though I didn’t have the words to articulate my feelings at first, I soon understood that I carried a mother wound, one that enhanced my longing for a wise woman, a sage who could point me down the path of the feminine way and hold space for all I was and all I carried on the journey.

My experiences and study led me to see that we have a Mother wound in our theology. This theological phenomenon is a collective wound that has affected our ability to perceive the need for the Mother as individuals. The spiritual death we experience in mortality, the fall into this telestial state, includes not only a separation from God the Father but also a separation from God the Mother. Just as unexamined pain—be it feelings of unworthiness, abandonment, or anger—can keep us from a clear perspective on what is happening inside and outside of us, our unacknowledged wound caused by separation from our spiritual Mother likewise obscures our vision of ourselves and the divine. The ramifications of what it means to be separated from our Mother are yet to be fully uncovered and understood.

None of us comes close to a complete understanding of who our heavenly parents are in this life, yet having an obscured or limited view of who we are doesn’t mean that They aren’t available to us. On the contrary. I have found that it is in the recognition of the distance and the desire to close the gap that we are tenderly cared for. The goal is to remove as much of the distortions and noise around our true essence and beauty, and thus Theirs, as we can. Simply put, I believe that what Joseph Smith said—those who do not comprehend the character of God do not comprehend themselves—applies to both the Mother and the Father. And so I wonder, How is it possible to know ourselves wholly if we do not know the Mother?

Stepping into the dark unknown creates space in our hearts for greater comprehension of the eternal interplay between light and shadow. Our very presence here in the realm of the roots conveys our willingness to dive down deep, to progress on individualized yet profoundly interconnected paths toward the divine. As Jesus did, we face our shadows and the forces that would divide us to find greater light. We experience pain as a part of the path to becoming and move through it in order to shed old ways that no longer serve us. We begin to sense that the degree to which we feel and acknowledge our soul’s discord is the degree to which we can fully embody the joy of progression. Fear and faith. Light and dark. Feminine and masculine. These are not ultimately opposing forces but ones that we embody in dynamic interplay, working together for our good and wholeness. Wholeness, then, is not about becoming perfect. It is meeting and accepting our true selves. And because we are ever-changing beings, actively working toward harmonizing these aspects of ourselves is what it means to be truly awake and alive.

While so much of what we find in our personal descents into the teeming underworld is individualized—unique experiences, histories, and struggles—as we journey through this abyss, we find the Mother leading us down deeper to the source of our shared internal pain. If we look carefully, with time we begin to see that our collective wounding begins as a point of basic confusion about our natures as divine children of heavenly parents. Generations of false traditions have spread confusion around the true nature of the divine femininity and the divine masculinity They embody.

Since the beginning, the fruit of this wound has been and continues to be unrighteous dominion, systematized in the world as patriarchy. Patriarchy—a social system and hierarchical structure in which men hold primary power and predominate in political leadership, moral authority, social privilege, and control of property—has shaped our views of women and men for millennia. It is the fabric and face of every hierarchical social, political, and economic structure, and our greatest root of discord. Placing oneself above another was the first sin story (Gen. 4:1–16). In the world of government and commerce, we come up against the reality that “we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places” (Eph. 6:12). Because they rely on inequality, hierarchical structures of power cannot survive in Zion. Love cannot prevail in any instance in which an individual desires to maintain control. Where Zion is, so are the “pure in heart”—souls fully committed to egalitarianism, shared property, and care for the least of these.

Patriarchy doesn’t only disenfranchise women. It subjugates anyone who does not fit the narrow definition of “worthy” by the few upholding power. Patriarchal masculinity estranges boys and men from their selfhood as much as patriarchal femininity estranges girls and women from their selfhood, just in different ways. It demands that men hold power above rather than with, keeping them from loving with all of themselves. Through the media, patriarchy tells us on a daily basis that men in power are able to do whatever they desire, and that that freedom is what makes them men. Patriarchal masculinity requires boys and men to uphold ideals of manhood that get in the way of loving justice between a woman and a man. The solution to this imbalance, as we know, is the perfectly just love of Jesus the Christ. As bell hooks, cultural critic and feminist theorist, puts it so poignantly in her book All About Love, “Loving justice for themselves and others enables men to break the chokehold of patriarchal masculinity.”

Jesus embodied attributes of divine masculinity and divine femininity. Among those men in Israel who wielded corrupt power, the scribes and Pharisees of His day, He compared Himself to a mother hen desiring to gather her chicks (Matt. 23:37). Was He rejected because of His resemblance to the Mother? His consistent appeal to the world to embrace feminine aspects of deity—compassion, nurture, unity, intuition, community—not only left him quite friendless but also made him an enemy to the institutions that harbored contempt for any teachings that would suggest the prostitute was equal to the priest. He sacrificed His life for the truth of humankind’s equality before God. Giving Himself over to death, He was received into the arms of the Mother, She who discerns and nurtures in the underworld and who co-reigns over the re-creative forces of the cosmos. He offers healing and wholeness to us as a connective bridge between heaven and earth, through which our souls pass into the arms of our Mother and Father to rest eternally.

Discussion Questions:

Join our online chat community.

When you contemplate the various meanings of the roots, what life experiences related to that realm come to mind? Why might those experiences be daunting, intimidating, or scary, and why are they also necessary?

In The Universal Christ, Richard Rohr writes "Feminine power is deeply relational and symbolic—and thus transformative—in ways that men cannot control or even understand. I suspect that is why we fear it so much." Do you agree? Have you felt or seen this fear of feminine power? What are expressions of this fear in the world? In yourself?

Kathryn Knight Sonntag is the Poetry Editor for Wayfare and the author of The Mother Tree: Discovering the Love and Wisdom of Our Divine Mother and The Tree at the Center.

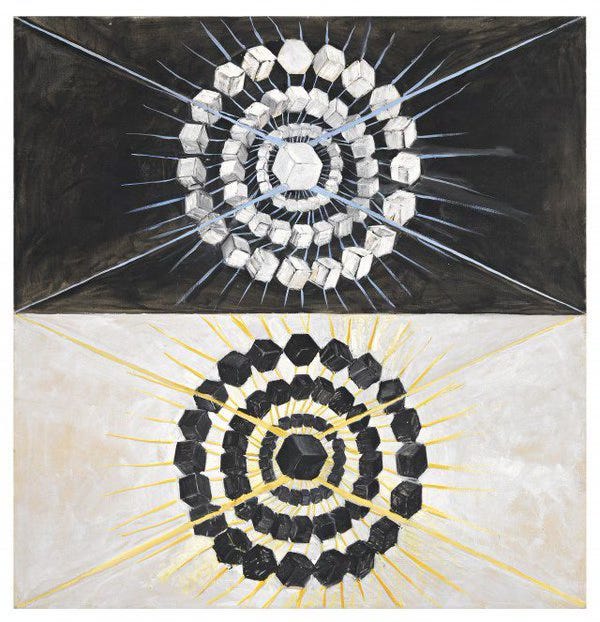

Art by Hilma af Klint.