I’ll tell you a story from an old Russian novel:

Once upon a time there was a peasant woman, and a very wicked woman she was. When she died she did not leave a single good deed behind, so the devils caught her and plunged her into the lake of fire. Her guardian angel stood and wondered what good deed of hers he could remember to tell to God. “She once pulled up an onion in her garden,” said he, “and gave it to a beggar woman.” And God answered, “You take that onion then, hold it out to her in the lake, and let her take hold and be pulled out. And if you can pull her out of the lake, let her come to Paradise, but if the onion breaks, then the woman must stay where she is.” The angel ran to the woman and held out the onion to her. “Come,'” said he, “catch hold and I'll pull you out.” He began cautiously pulling her out. He had just pulled her right out, when the other sinners in the lake, seeing how she was being drawn out, began catching hold of her so as to be pulled out with her. But she was a very wicked woman and she began kicking them. “I'm to be pulled out, not you. It's my onion, not yours.” As soon as she said that, the onion broke. And the woman fell into the lake, and she is burning there to this day. So the angel wept and went away.

It’s a marvelous parable with a nice Russian ending. Islamic folklore gives us a similar story with a different ending, about a man who likewise had never done anything good. He had even killed 100 people. At the end of his life he felt remorse, and went to seek a faraway temple where he might find forgiveness, but he died only a few steps outside his town. The devils and angels came clamoring for his soul, the angels saying that he was on his way to repentance, and the devils saying he had lived an evil life here in this city. And so God told them to measure the distance and see if the wicked man was closer to the city or to the temple. If he was closer to the temple, the angels could have him. If he had fallen closer to the city, the devils would get him. And as they began to measure, God began stretching the world, making the few steps out of the city worth a thousand miles, placing the wicked man at the foot of the temple. And so the man was let into heaven.

These two fables have very different endings, but share a surprisingly similar portrayal of God and the angels. In both stories, the angels are not sentinels, guarding the gate, securing the castle with a key and passwords. Instead they are out in the world, meeting people as they die, fending off devils. Trying to get all people into heaven. And in both stories, the angels’ strategy is the same: It is to find goodness, and to use that goodness to pull us into heaven.

Though my life has not been as hyperbolically evil as the Russian woman or the Muslim man in these stories, I can look on a period of my life as a catalog of failures. I was called as ward clerk by a departing bishop whom I loved. Under his direction, I was a clerk in name only and instead was tasked with making sacrament meetings more fulfilling. I called speakers, assigned talks, and proposed topics. This experience was short lived, however; when a new bishop was called, I began doing more secretarial tasks. The new work was uninspiring, but beyond that, something about how this new bishop orchestrated the ward felt heartless, bureaucratic, wrong-spirited. Even so, the first and second councilors were people I enjoyed well enough. Yet I would have enjoyed them more if it hadn’t been for my general gloominess about the state of affairs.

At one point, the second counselor sent me a story he had written. He never responded to the feedback I gave him, and I thought he must suspect my antipathy. I wondered if I should have been more effusive in my compliments and kinder in my critiques. But it was neither here nor there. He was not a person of low confidence. He was a jokester and fun to be around. If I hadn’t always been in a hurry to leave church after another long, rambling, pointless bishopric meeting, we might have become close friends, but we did not.

And then, at a youth activity at the chapel, this man had a seizure and was rushed to the hospital, where doctors found a brain tumor. This was a man in his late thirties, with five children. He missed a lot of bishopric meetings after that, lucky him. But he came when he could. Over the following year, I watched him shrivel. He lost his balance easily and almost fell most Sundays as he tried to climb up to the stand. And every testimony meeting where he was present, he would get up and make some jokes, and testify.

A couple months before he died, I remember noticing that his once plump and jovial body had become entirely desiccated. He had a scar across his head, from an ineffectual surgery. And he tottered as he stood bearing testimony. He talked about mistakes he made as a kid, and how he must have caused his mother a lot of grief. And he went on to testify that God’s grace, like a mother's love, sees through our mistakes and childishness.

During his whole testimony, my son Clarence was making a racket in the aisle. And I thought, my son, you are missing this. There is nothing so commanding, so profound, so glorious as a man in his humiliation. A man who jokes with death. A man who believes as purely as Job.

And I thought about my failures and childishness. I had had plenty of time to befriend him. The man even sent me a story he had written. By the time he got his diagnosis, we could have been great friends. We could have had inside jokes. Mine could have been the family he called for a blessing or a babysitter. But we weren’t. I wasn’t. And why? Because I was upset about how the bishop orchestrated the ward. But that’s the thing. The body is not a bureaucracy. The ward is not the bishop. As Paul says, a body is not a head. All parts are a part of the rest. And the church is the body of Christ. We are the body of Christ. It’s us, it’s between us. We animate it, or let it atrophy.

And I had done the latter. After his death, his family decided not to hold a funeral. I was upset—I thought he would have liked a funeral. He was a man who bore testimony every chance he could. He was a people person, a storyteller. But his death had been long and drawn-out, and the family was probably exhausted from the attention and ready to move on. But still, it would have been nice to have a funeral. They did eventually decide to invite friends to a graveside service. And I thought, well that will be nice.

But by that point, my family was processing some trauma of our own, and my mind was so preoccupied with planning an upcoming move that I totally spaced the service. I didn’t show up. I had failed him again, in life, and now in death. And I had had the gall to be upset that they hadn’t planned a funeral.

I remembered that short story he had sent me, and that he had never responded after my feedback. And I thought, darn it. Darn it. So many failures. But I read through the story again. It was about him as a boy having to shoot the family dog because it had eaten coyote poison. And it was a pretty good story. Reading my own comments, I saw that I had said some really nice things.

I was so grateful—I had not failed entirely. I had read his story. I had made thoughtful remarks. I was kind and generous. Who knows why he never responded to my feedback. But I saw our interaction as an onion.

Another great failure of mine at the time was when I failed to secure a new bed for a man named Bobby before he passed away. I was tasked with getting him a new mattress on Sunday at another uninspiring bishopric meeting, and I planned to do it the following Saturday, but by that time Bobby was already dead. When I learned that Bobby passed away, my first thought was, oh I wish he could have spent his last night on a new mattress. That was an onion. My second thought was much less holy: I thought, well at least the church saved some money.

That week a lot of the ward leaders were away on Trek, but we were home, and I was able to go and prepare Bobby’s body. I was able to dress him in my temple clothing. There is a man in a cemetery in Waltham, Massachusetts, buried next to his mother, in my temple clothes. That is an onion.

I believe that God is waging a very different kind of war than we often imagine. There are no scales he cannot unbalance, no distance he cannot change. The moment we turn to repent, we are a thousand miles from sin and a foot from the temple. The logic of God’s grace is unlogical.

This is a truth that hit me again just before Christmas as I read one of my favorite Christmas poems. Here is an excerpt that will shed light on God’s tactics.

This little Babe so few days old Is come to rifle Satan's fold; With tears He fights and wins the field, His tiny breast stands for a shield; His martial ensigns cold and need, And feeble flesh His warrior's steed. My soul with Christ join thou in fight; Stick to His tents, that he hath pight. Within His crib is surest ward; This little Babe will be thy Guard. If thou wilt foil thy foes with joy, Then flit not from this heav'nly Boy!

This poem draws attention to what was perhaps most surprising about God's condescension to the earth. People had imagined the coming of God to be powerful, forceful, undeniably grand—this is God we're talking about. But instead, he comes just as weakly, unremarkably, and miraculously as any other new born baby. Except, perhaps a little more humbly than most. In a stable. And he's almost immediately put on the defensive, as the family flees into Egypt to escape Herod's genocide.

And all this speaks to the kind of war God has come to wage. Not a battle with swords, not a battle for popularity, not even a battle of ideas. But a battle to end battles. A battle that undoes the logic of war. The final line uncovers the depth of his subversive tactics. God defeats his enemy not by plunging a sword through their heart, or besting them with strategy or technology. He overcomes them with joy. Joy is the weapon of God.

And he brings us to heaven not by force, but by our own goodness. Here is need, he says. Here is want. Here is a naked chest. Here are babies crying. Help. And sometimes, remarkably, we do. Not every time. Far from every time. But sometimes we provide. Sometimes we cover nakedness. Sometimes, we share an onion. Sometimes we comfort the crying baby. And the baby calms, and beams back at us, and we are foiled by joy. God has lassoed our hearts. And he is pulling us to heaven.

Joshua Sabey is an award-winning writer and director. His recent book, Ali the Iraqi, was published by BCC press. His latest documentary, American Tragedy, won best documentary at the Boston Film Festival where it screened alongside Taika Waititi’s Jo Jo Rabbit.

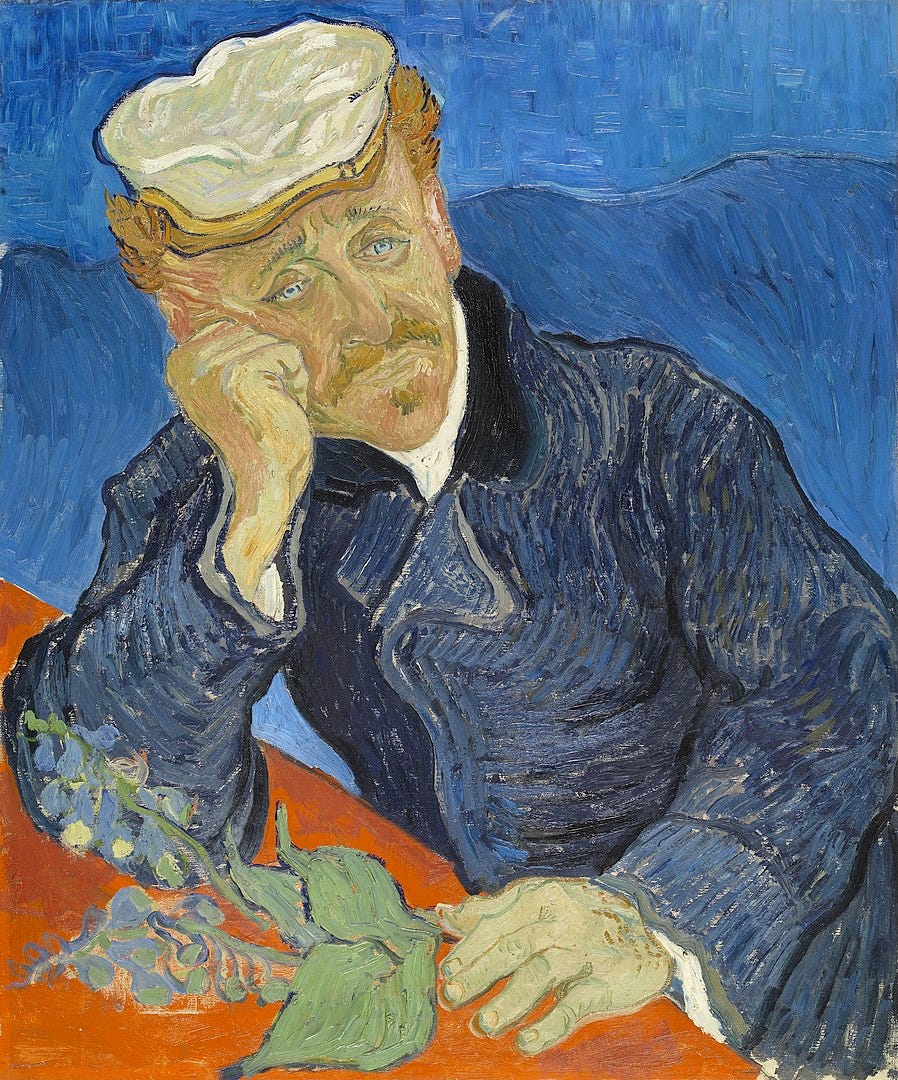

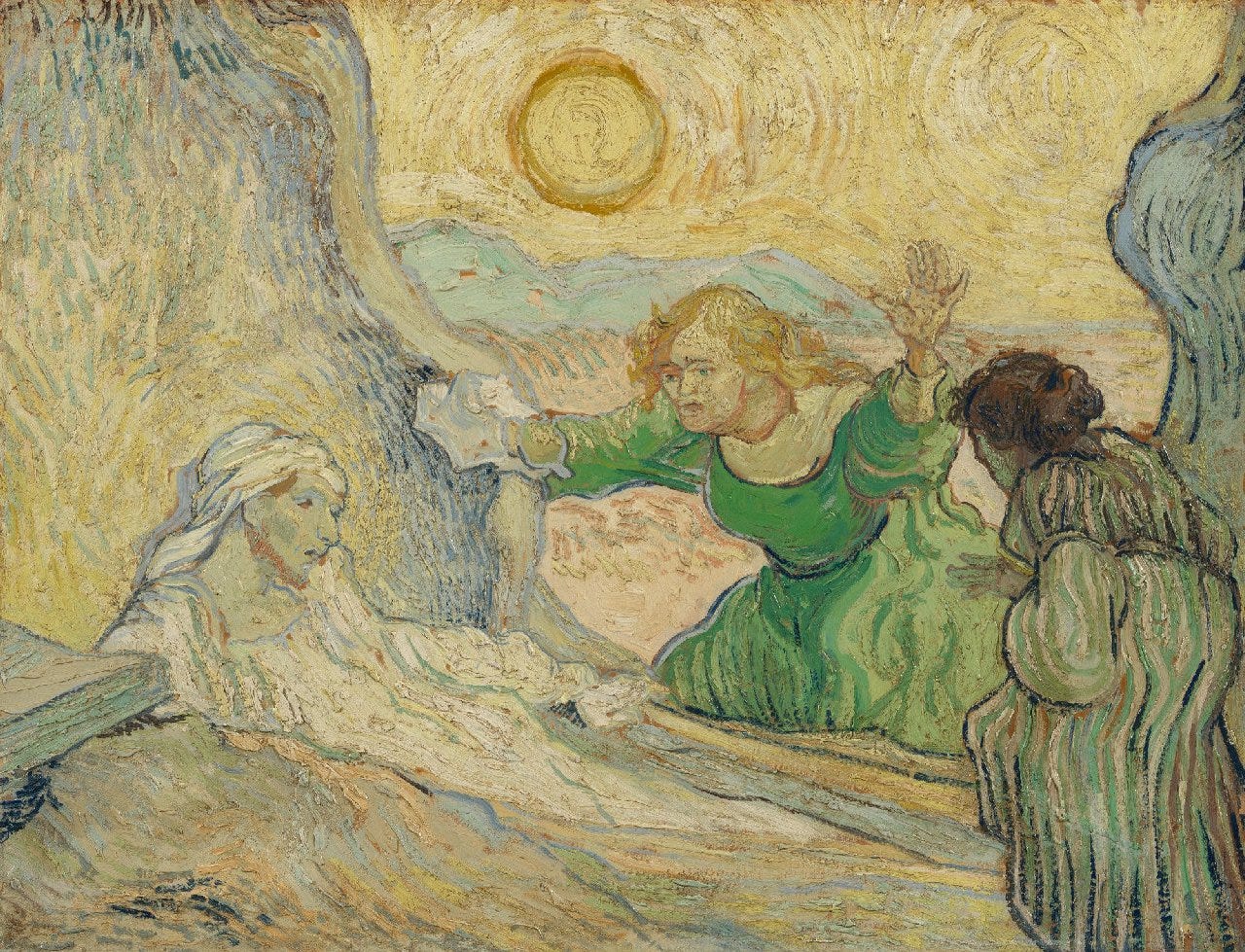

Artwork by Vincent Van Gogh.

Intriguing and lovely article. It’s embarrassingly easy to relate to uninspiring meetings. (In my case it’s oh so cute Relief Society activities🤣) I’m adding it to my collection of writings that inspire me to love God increasingly and try to be more like Him.

I can think of a few onions of my own. Thanks for sharing Josh :)