In his novel interpretation of how human cultures take shape, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio assigns an unexpected pride of place to feeling, affect, and emotion. Cultural development itself can only be understood, he argues, by recognizing the role of “feelings” as the “motives” behind intellectual creation, as the “monitors” of how our culture succeeds or fails, and as the compass for “negotiating” new directions of cultural development. Culture, unlike evolution, moves relentlessly beyond mere survival. It moves toward the satisfaction of desires, and we experience that satisfaction in the realm of feelings. In other words, “the affects related to fundamental desires,” are the core generators of all human cultural development, and these desires include the sensation of thriving, “the experience of elevation” and of “awe and transcendence.” What we really aspire to, what we register and what we shape our lives and our cultures around, are particular kinds of feelings. What are the theological implications of this fact?

It has been common since Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century (and even before) to insist that God does not experience love as an emotion. Why? Because emotions involve bodily changes and since God can neither change nor be posited as embodied, love must be “intellective” rather than “emotional.” Yet the human telos—the end which all human striving has in view—is happiness, or better yet, joyfulness. And as the theologians have said in agreement with Damasio, “a happiness which is only ‘thought’ or ‘willed’ is no happiness.” Joy is “patently an affective experience,” and “the only way to experience happiness is to feel it.”

The question is, must this be true of God as it is of persons? It seems inescapable that the joy that God knows and presumably hopes for his creation must be an experience of joy. Knowledge of or about joy is not joy. Reason, justice, wisdom—no divine attribute can itself constitute the experience of joy that is integral to the Divine Being. If love is the mode of God’s being (1 John 4:8), and joyfulness the condition he wishes to share, then affect—responsiveness to the other who constitutes any loving relationship—must be the essential core of God’s nature and of anyone made “in his image and likeness” and designed to become more like him. The divine nature cannot be conceived as independent of or purged from affect, feeling, responsiveness to and entanglement with the other. Love is affect in its holiest form.

God, following this line of reasoning, is more like us—and we more like him—than theology historically imagined. Here, too, positive developments in Christian theology have been underway for some time. Most contemporary theologians recognize that God must be “ethically good because the development of moral personality appears to be at least included in his purpose.” Such a purpose entails at least a minimal congruence between God’s goodness and the goodness to which we aspire. God and his perfections are our model, in simplest terms. John Burnaby sees that a critical turning point in Christian history occurred when Augustine failed to recognize this point, and built much of succeeding Christian thought on that error. In his formulation of an original sin imputing guilt to all, Augustine forfeited moral and rational coherence—and he could only do so by differentiating the moral sphere in which we humans participate from a different morality, “higher than human, . . . the more inscrutable and so much the further removed from ours.” No matter if the resultant concept of justice is “disturbing” to our moral or rational sensibility, as indeed it was disturbing to Augustine, his contemporaries, and is to many moderns. “Should Christians,” asked Augustine’s nemesis Julian of Eclanum, “really think that a merciful, loving God would torture infants just because they were not baptized?”

Gregory of Nyssa’s declaration anticipates a long line of dissent from Augustine’s position. “What is different in nature from the Good is surely something other than the Good,” the fourth-century Church Father from Cappadocia wrote. One of Hugo Grotius’s most audacious claims in the seventeenth century—one with the potential to relitigate the nature of God in ways consistent with its Johannine roots—was the proposition that God inhabits the same moral universe that humans do. “God himself cannot effect, that twice two should not be four; so neither can he [bring about] that what is intrinsically evil should not be evil. . . . Such is the nature of evil actions. . . . Therefore God suffers himself to be judged according to this rule.”

David Hume affirms the same principle in the next century. His fictional character Demea claims that we must not attribute human sentiments (like “love”) to God. Cleanthes responds, “The deity, I can readily allow, possesses many powers and attributes, of which we can have no comprehension: But if our ideas, so far as they go, be not just, and adequate, and correspondent to his real nature, I know not what there is in this subject worth insisting on.” The congregationalist George MacDonald added his concern in the nineteenth century: “To say that what our deepest conscience calls darkness may be light to God, is blasphemy; to say light in God and light in man are of differing kinds, is to speak against the spirit of light.” This idea received a more forceful formulation in the shadow of Auschwitz. Elie Wiesel has a character protest that if our truth “is not His as well, then He’s worse than I thought. Then it would mean that He gave us the taste, the passion of truth without telling us that this truth is not true!”

Even those who claim a Restoration of truth and authority need to recognize our very real human limitations, and speak with caution and meekness when we presume to approach the God who dwells in everlasting burnings—in actual deed or through human words. Still, we might affirm with Stephen Webb, “Whatever God is, he is much more than what we are, but he is still more like us than he is like anything else.”

Terryl Givens is Senior Research Fellow at the Maxwell Institute and author and coauthor of many books, including Wrestling the Angel, The God Who Weeps, and All Things New. To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, first subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."

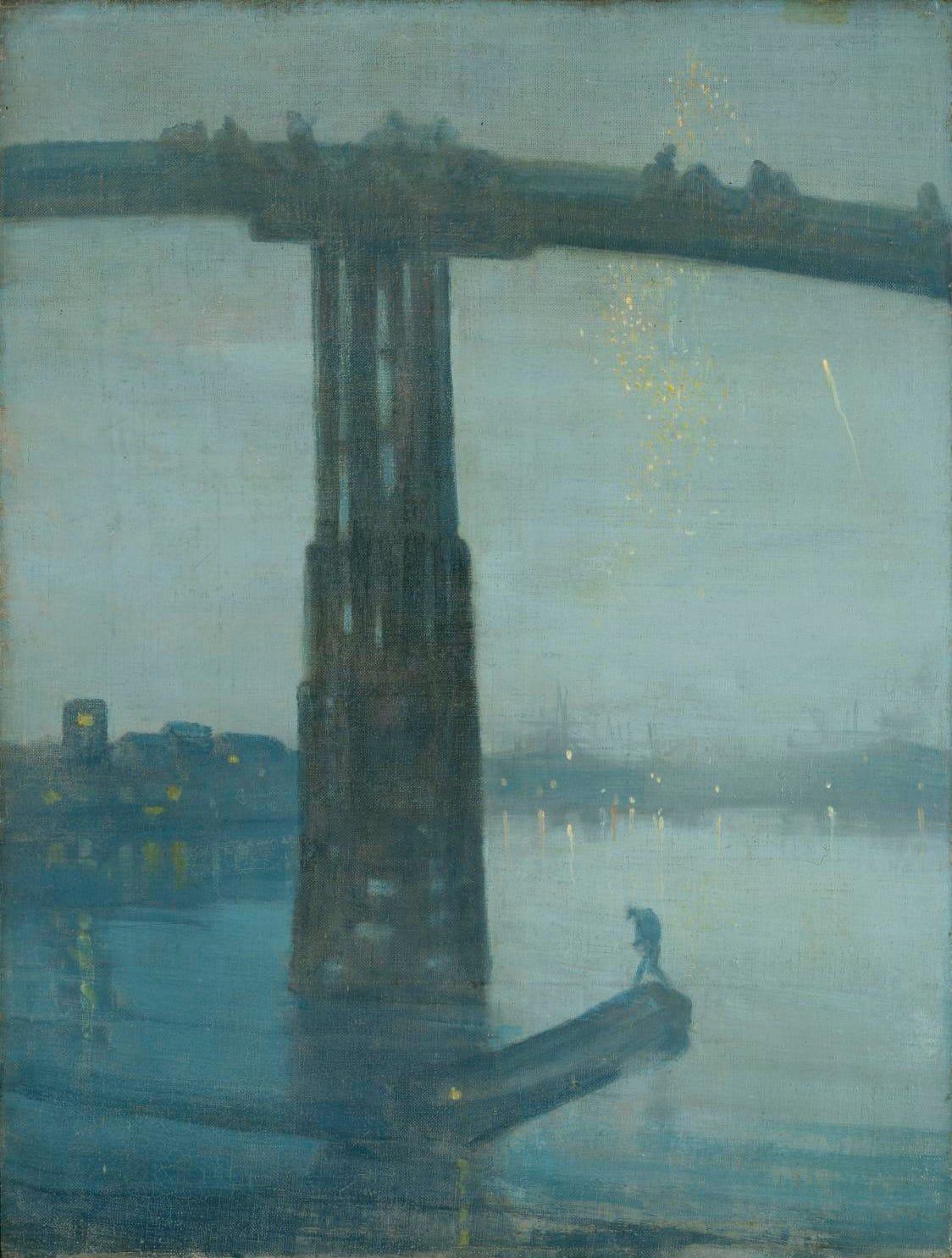

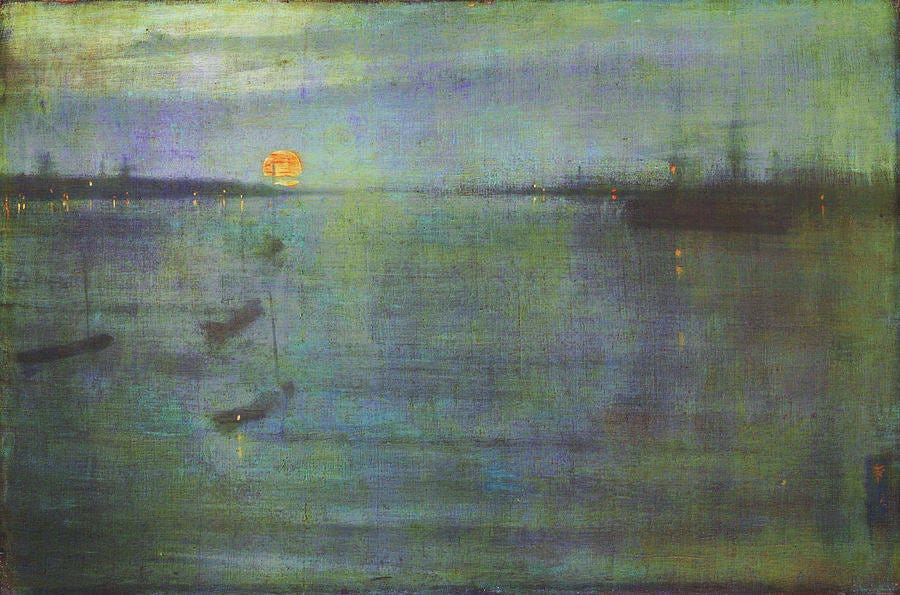

Art by James Abbott McNeill Whistler.

Audio produced by BYUradio. Subscribe to listen at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or Youtube.