Celestial Navigation

When European explorers first chanced upon the islands of Polynesia in the sixteenth century, they were confronted with a puzzle. These mariners from Spain, Holland, and England had themselves only recently developed the ability to cross the oceans and reach these remote islands. Yet on island after island in this unfathomably vast stretch of sea they found people already living there—people who lacked large ships, compasses, sextants, or any of the other devices vital to European oceanic expansion. How had the inhabitants first reached these remote islands when they appeared to lack the seafaring technology necessary for such voyages?

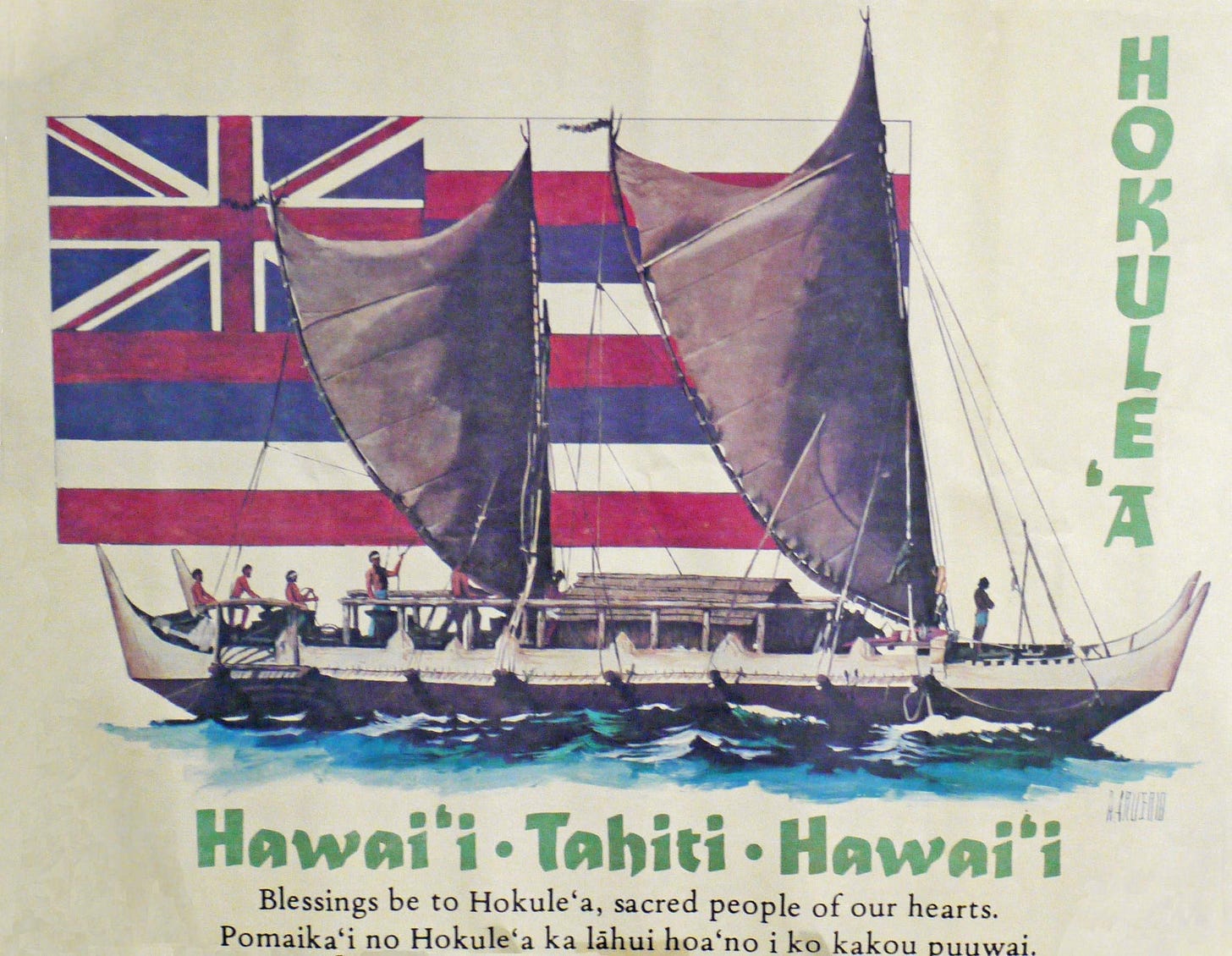

A belief took hold among Westerners that the South Pacific was randomly populated by sailors blown off course by storms. But Polynesians themselves believed otherwise. In Hawaii in 1973, anthropologist Ben Finney, artist Herb Kawainui Kāne, and sailor Charles Tommy Holmes organized the Polynesian Voyaging Society to help prove the alternative theory that the native Oceanic peoples had reached their island homes via purposeful trips, not aimless drifting. The Society’s first project was to reconstruct a traditional Polynesian double-hulled voyaging canoe and make the 2,500-mile journey from Hawaii to Tahiti using indigenous techniques and knowledge.

Since no examples of actual ancient voyaging canoes were available as models, the design was based on eighteenth century drawings of canoes made by artists and draftsmen employed by the British Naval Captain James Cook and other early explorers of the Pacific. After two years of construction, the Society had a sixty-two-foot, double-hulled canoe ready to sail with a crew of twelve.

At first the group couldn’t agree on a name for the vessel. Then Herb Kāne had a vision. "One exceptionally clear night, I dreamed of stars. My attention was attracted to Arcturus, which we call Hokule'a, ’star of gladness.’ It appeared to grow larger and brighter, so brilliant that I awoke.” The canoe now had its name: Hokule'a.

Stars often communicate important messages. You could even say they are a language of God. “Let there be lights in the vault of the sky to separate the day from the night, and let them serve as signs.” In ancient times, learning to read these divine signs was difficult, reserved for wisest or holiest. Sometimes, God taught such knowledge face to face. Abraham was taught the names and properties of the stars. Moses received a direct vision of “the heavens, they are many, and they cannot be numbered unto man; but they are numbered unto me.”

But even without a private divine tutorial, those sensitive to spiritual things could perceive God’s messages written in the sky. The magi from the east (very possibly Zoroastrian astrologers) observed a new star and understood its meaning. “They set out; and there, ahead of them, went the star that they had seen at its rising, until it stopped over the place where the child was. When they saw that the star had stopped, they were overwhelmed with joy.”

Stars testify of Christ in other ways too. The Prophet Joseph Smith revealed that Christ is “the light of the stars, and the power thereof by which they were made.” Perhaps that is why at Jesus’s death the stars fell dark. At the Second Coming it is prophesied that likewise “the stars shall refuse their shining.” The Apostle Peter compared Christ to a “light shining in a dark place….a day star that rises in your hearts.” And as he tells us himself in Revelation, “I, Jesus, am the Bright and Morning Star.”

Celestial navigation is the art and science of finding your way by the sun, moon, stars, and planets. The Polynesian Voyaging Society was convinced their ancestors had mastered this art to explore and settle the South Pacific. Unfortunately, they couldn't prove it. Knowledge of traditional wayfaring had essentially disappeared among Polynesian cultures after contact with Europeans. Not one person on Hawaii possessed the skills to sail Hokule'a. So the Society began a search across Polynesia to discover if anyone on the other islands still possessed knowledge of traditional navigation.

The quest took them to the tiny Micronesian island of Satawal, a solitary coral atoll about one mile long, with a population of about five hundred people. The Satawal community was the last to practice precolonial maritime wayfinding, a sacred knowledge passed from elder to apprentice. But there was a problem. The six master navigators that remained refused to reveal their ways to outsiders. All the navigators, that is, except for one. Mau Piailug, the youngest of them, had come to fear that knowledge of traditional navigation would die in his own culture, just as it had in Hawaii. His efforts to train the next generation of Satawalese had largely failed; they were more interested in Western education and culture. So despite the taboo against teaching outsiders, and despite barely knowing any English, Mau Piailug agreed to navigate the Hokule'a and teach his knowledge to a member of the crew, Nainoa Thompson, a direct descendant of Kamehameha I, the first ruler of the Kingdom of Hawaii. “In myself,” Thompson revealed later, “there was a deep desire to learn navigation, to learn who I am by knowing where I come from.”

There was a reason the young people in Satawal had resisted Piailug’s lessons. Becoming a master Polynesian navigator involved learning an impossibly complex set of skills. First, you had to learn to read the night sky. Unlike planets, stars hold fixed celestial positions year-round, changing only their rising time with the seasons. Each star has a specific declination granting a bearing for navigation as the star rises or sets. Polynesian voyagers would set course by a star near the horizon, switching to a new one once the first rose too high. They would memorize a specific sequence of stars for each route. They knew the sky the way we know the melody of a favorite song or the face of a beloved.

But because clouds can obscure the sky, Polynesian navigators also learned to wayfind with an astonishing array of other inputs, such as the color, temperature, and salinity of seawater; floating plant debris; sightings of land-based seabirds flying out to fish; cloud type, color, and movement; wind direction, speed, and temperature; the direction and nature of ocean swells and waves; and the estimation of the speed, current set, and leeway of the sailing craft.

To become adept at this required many years of training, and even then not everyone reached the point of being a palu, or fully initiated navigator. Those who did were seen as equal or superior to the village chief. Mau Piailug was a palu and thus capable of executing the great navigational task entrusted to him, and teaching the art to others.

On May 1, 1976, to the sounding of ceremonial conch shells, Hokule'a left Honolua Bay, Hawaii, on her maiden voyage to Tahiti. Thirty-three days later, Hokule'a arrived in Papeete, Tahiti, to a jubilant crowd of more than seventeen thousand—over half of the island—who had come to welcome their brothers to shore and witness the rebirth of an ancient art. It was the first time in eight hundred years that Polynesian sailors navigated between the two islands by canoe, guided primarily by the stars.

Since then, the Hokuleʻa has undertaken voyages to other islands in Polynesia, including Samoa, Tonga, and New Zealand, and has even successfully circumnavigated the globe. And before his death in 2010, Mau Piailug trained and initiated dozens of navigators into palus, ensuring the survival of his sacred art.

Unfortunately, for most of us, the stars are fading from view. The first electric streetlight was invented by Pavel Yablochkov and installed in the Galeries du Louvre in Paris in 1876 (thus earning it the nickname City of Lights). Since then, electric lights have rapidly expanded across the globe, crowding out the lights of heaven. More than 80 percent of the world’s population, and 99 percent of Americans and Europeans, live under a haze of grayish glow that obscures our view of the stars. In our Promethean quest to control nature, we risk becoming blind to it.

Some pockets of starsight remain, though they must be sought out. When I was fifteen, I attended a weeklong scout camp in the Pine Valley Mountains of Southern Utah. One day, after a delirious, joyful afternoon of pine-cone warfare with a rival troop, a friend and I took our sleeping bags and trekked out away from the camp to sleep out in the open. We came to a clearing and watched the sun descend and the vast millions of stars emerge in clusters across the sky. Suddenly, a light streaked across the canopy, and then another. A meteor shower. We watched for what seemed like hours, in silent wonder, pulled upward into the bosom of eternity.

The stars still have messages to convey. We are ever swirling beneath a vast canvas of divine creativity and love. As we become more sensitive and skilled wayfarers, we not only seek out the guiding light of the stars, but stop to witness their wondrous dance.

Zachary Davis is the Editor of Wayfare and Executive Director of Faith Matters.

My grandparents would sit out on their lawn in Toquerville (at the foot of the pine Valley Mountains) and look up at the stars and sky. I would not say they were celestial navigators but they did have an awe of creation.

I really enjoyed reading this. A great history lesson and provocative metaphor of celestial navigation.