The word “authenticity” does not appear in scripture, but it is on a lot of people’s minds. Authenticity is defined as the quality of genuineness—of being what a person or thing is claimed to be. In the testimonies prepended to the Book of Mormon, the witnesses attest that the plates are real, though they can only say for sure that they have “the appearance” of gold. The earliest document of church doctrine, the Didache, provides more than half a dozen keys whereby a saint may know the true prophet from the false, those one should heed and those one should reject. When “genuine” is used in the New Testament, it is generally paired with love. Let your love be “genuine,” Paul tells the Romans (12:9).

How does authenticity relate to the self? Does the life of discipleship threaten authenticity? At its core, that may seem to be the case. In the earliest text known to be written by a Christian, Paul the apostle writes to a small flock of believers in Thessalonica, in modern-day Greece. Composed perhaps two decades after the death of Jesus, the introductory lines refer to those early Saints—as disciples were called—as persons who became μιμηταὶ ἡμῶν ἐγενήθητε καὶ τοῦ Κυρίου, or “imitators of us and the Lord” (1 Thes. 1.6).

Imitation and authenticity seem to be opposites. The challenge to change one’s inner nature, to conform one’s aspirations and actions and thoughts to those of another seems the absolute essence of inauthenticity. Is modeling our life on Christ mere conformity to an inherited religious model, or is it the deepest version of integrity of which we are capable?

First, let us digress a moment into science—specifically—human psychology, and what it tells us about imitation. We are biological entities, and like all other biological entities, we have inherited needs, appetites, inclinations, and capacities. Are there any ways in which we are unique as a species? Neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga writes: “Many people are watching for and testing for imitation in the natural world but have found little evidence of it, and the fact that when it has been found, it has been of limited scope, indicates that the ubiquitous and extensive imitation in the human world is very different.”1 Here we find a direct engagement with our question: imitation—in its human variety—has something about it that differentiates it from mere animal mimicry.

The philosopher and historian Rutger Bregman says simply, “The mental skill that most differentiates humans from other primates is social learning.”2 We can deliberately select from the infinite array of human practices, and consciously, deliberately work to convey those practices—from writing to building aqueducts to worshiping the Divine—to our children or our peers. Evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich devotes an entire book to “the uniqueness of the human capacity for social learning—whose fruit is culture. Our brains are unique in their abilities to learn from others.”3 What historians, biologists, and neuroscientists are describing as a uniquely human gift is in our ability to choose which models we will be influenced by; what values will we choose to embrace? This may be news to cognitive science, but was understood by the fourth-century critic of Augustine, the much maligned Pelagius. He argues that, contrary to Augustine’s teachings, we are not sinful by nature. The fact is we are “essentially social: we become whoever we are largely through imitation.”4

What futures will we choose to steer towards? What influences, words, or actions of others will we decide to emulate, and which will we reject as unworthy of imitation? Ironically, imitation is one of those capacities that make us human. To imagine a capacity to act in an entirely spontaneous, self-directed way, untainted by external ideals or models, is a pipe dream. What would such an imagined life even look like? (The wolf-child of legend?) Such “authenticity” is not only an illusion; the sacrifice of our capacity for imitation would represent the loss of one of the most conspicuous markers of our humanity.

One word that Christianity often employs as code for “the imitation of Christ” is “obedience.” Obedience, like imitation, rubs against the grain of contemporary culture. It has all those connotations of authoritarianism, inauthenticity, and robot-like conformity. In this regard, I have found the words of Timothy Radcliffe to be a powerful corrective to the cultural baggage of obedience. “The obedience of faith,” he writes, “is more like listening expectantly to a Beethoven string quartet than to obeying a police officer. It’s a response to the authority of its meaning.”5 No one compels us to love the music of Beethoven or a sonnet by Shakespeare. If we are attentive and open, susceptible to its beauty and power, then we respond to its sway over us. It washes over us, draws us toward a recognition of the rightness of this experience so far beyond the cacophony of traffic or the tedium of our own voices. The parallel is not perfect but it is close. We are drawn to Christ to love and imitate and yes, obey, because his love is non-coercive, his tenderness matchless, his every interaction with his friends and strangers the ideal of how any one of us can be most fully alive and responsive in this world of human relationship.

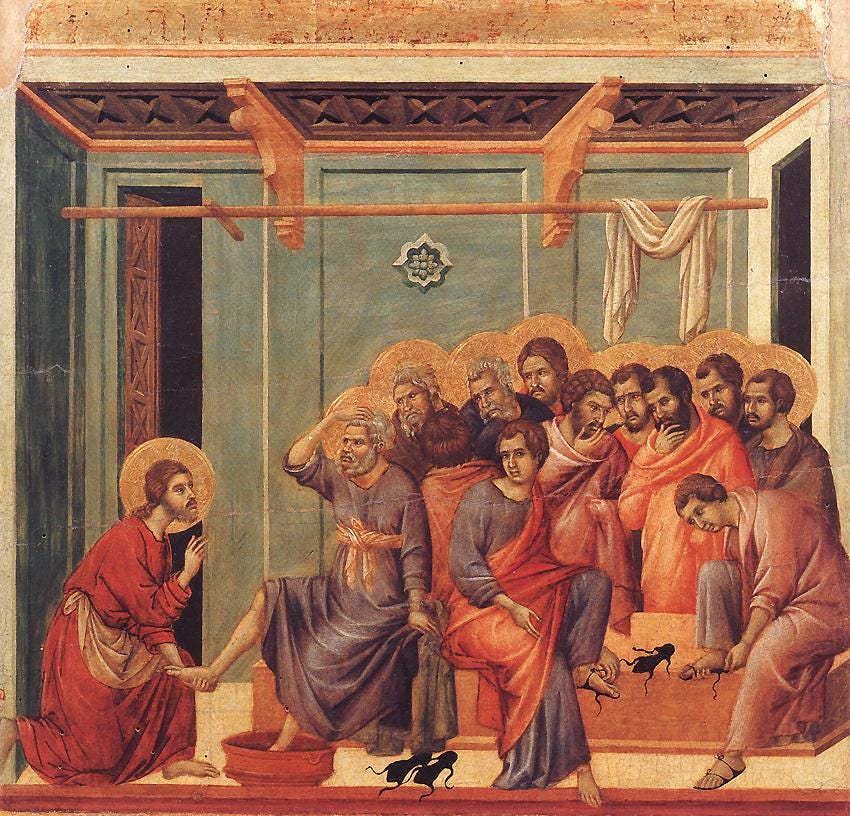

Artwork by Duccio.

To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, first subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."

Amazing!!