At age four, I attended my first funeral. I was very confused about death and what it was, but my mother explained to me that everybody dies and gets buried in the ground, and we don’t see them anymore. Then she reassured me that it was all okay because Christ died for us a long time ago and then came back to life, and now we will all (even my great-uncle Leon, lying in front of me in a casket) come back to life.

This is the first Atonement lesson I can remember, and I spent the entire year after that asking my mom over and over again when my Uncle Leon would come back to life. I thought I understood what Christ had done for me, but my understanding was as if I had seen a single picture of an oak tree and then declared that I understood the forest.

James E. Talmage writes, “Simple as is the plan of redemption in its general features, it is confessedly a mystery in detail to the finite mind” (pp. 76). This resonates with my experience.

The Atonement is difficult to comprehend. Since that first lesson, I have had many more lessons and conversations about the Atonement with family members, teachers, friends, missionary companions, and the Spirit itself. And sometimes I feel like I am still four years old, trying to wrap my head around a concept I don’t have the capacity to understand. It is difficult to comprehend something that is infinite and eternal while also being both intensely personal and full of enabling power, but I want to try. I want to do all I can to understand the Atonement so that I can fully appreciate my Savior and access the miracles he has made possible.

I believe Christ has performed the Atonement, but faith is not the same thing as understanding. My faith has grown through personal, powerful experiences of heavenly love. My understanding has only come through stories.

What We Talk About When We Talk About the Atonement

Humans are wired to enjoy and learn from stories. We use them to make sense of the world and our experiences, and we use them to communicate those thoughts and experiences with each other. By the time I was fourteen, I had heard the story of the Atonement many times and in many ways, and I thought I had a pretty good understanding of it. Then I heard Elder Boyd K. Packer’s 1977 talk “The Mediator.”

It was powerful.

This story is about a man who cannot pay his debts. Then a mediator steps in, pays them, and renegotiates the debt payment schedule so that the man won’t have to go to prison or lose his possessions. When I heard this, a cartoon light bulb in my head turned on. It was a complete paradigm shift. I felt like all of my prior understanding had been childish, and that I was now, finally, understanding the Atonement for the first time.

Was I finally understanding? No. Well, yes. I had seen a picture of the forest floor, dotted with moss and toadstools, dappled light landing in a beautiful pattern on the fallen leaves. I was understanding something new about what Christ had done for me, but still not the whole picture.

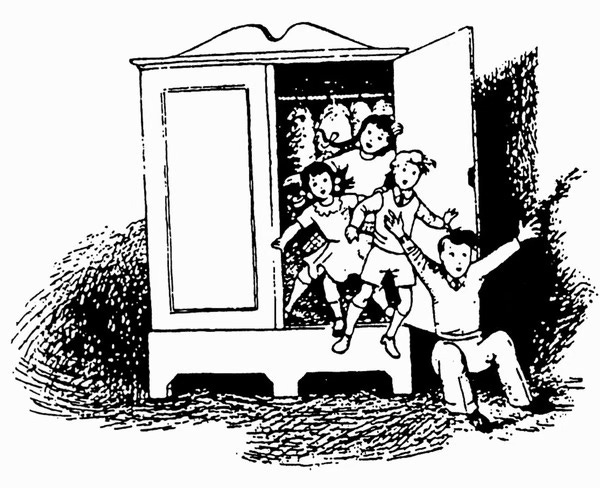

I had similar experiences with other stories, including Steven Robinson’s Parable of the Bicycle, the biblical story of Abraham and Issac, C. S. Lewis’s The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland’s story of brothers rock climbing in “Where Justice, Love, and Mercy Meet,” and George MacDonald’s The Light Princess. Each of these helped me conceptualize facets of the Atonement that I hadn’t understood before.

When we talk about the Atonement, we talk about it slant. We talk about bicycles or piano lessons, about war heroes or schoolboys who volunteer to take each other’s whippings. We talk about the enabling power of pure love, the greatness of a mortal sacrifice, and mountains of debts being paid by wealthy benefactors. We talk about cruises and parents, lions, princes, prophets, heart surgeons, and airplane pilots, even forests.

We talk about real-world experiences that are concrete and observable. These are experiences that we hope others can understand and relate to. When we talk about the Atonement, we use concrete, earthly symbols to explain the Savior and his mission.

The more I learn, as a creative writer, a Latter-day Saint, and as a reader and lover of fairy tales, the more I am convinced that the best tool available to help us understand the great and eternal sacrifice of our Savior, Jesus Christ, is the symbols and metaphors we find in stories.

Of course, the scriptures are full of good stories and powerful metaphors that can give us understanding, but they are not the only place these metaphors can be found.

Why Fairy Stories?

On March 8, 1938, J. R. R. Tolkien gave an Andrew Lang lecture at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. The title of the lecture was “On Fairy Stories,” and it is one of Tolkien’s most influential non-fiction works. In the lecture, he answers several questions: What are fairy stories? What is their origin? and—most relevant to our project—What is the use of them?

Tolkien defines fairy stories as those that contain “the nature of Faërie: the Perilous Realm itself, and the air that blows in that country.” According to Tolkien, fairy stories must contain enchantment and fantasy. They transport readers to a land where strange and wonderful things happen and where miracles are taken seriously.

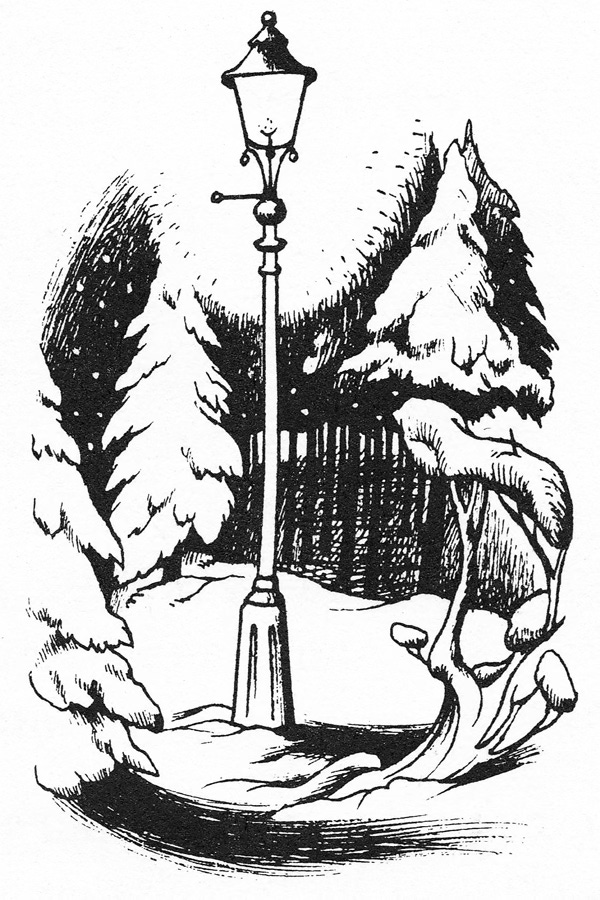

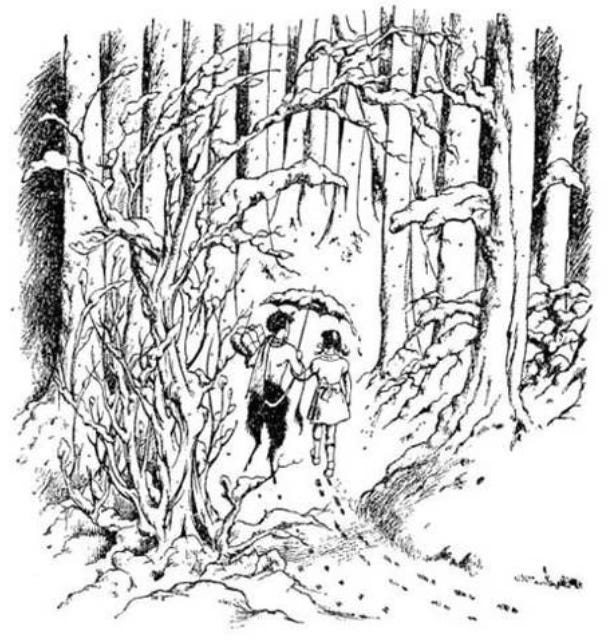

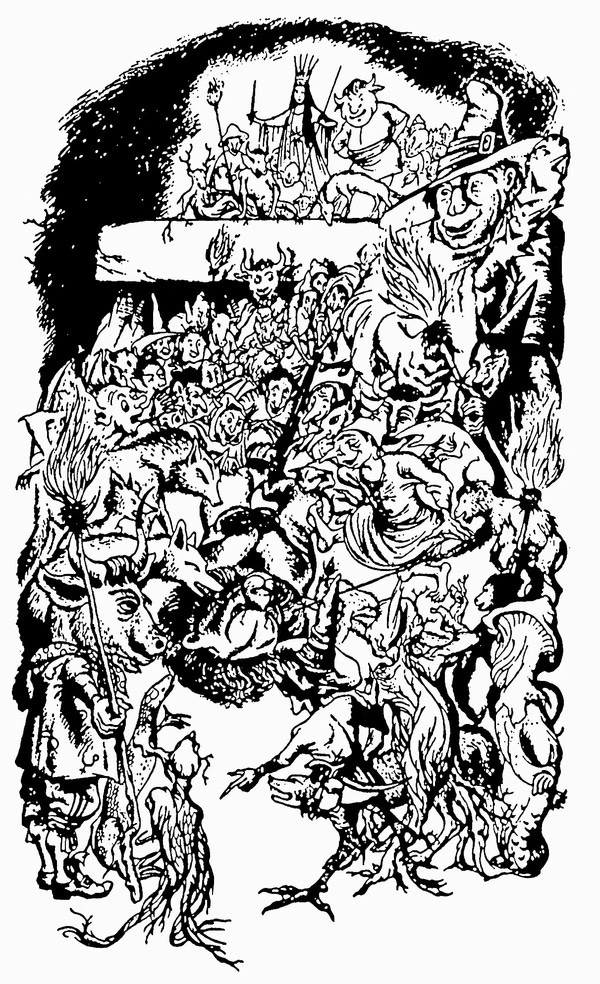

C. S. Lewis, one of Tolkien’s close friends, gave us the perfect example of that perilous realm when he wrote of Narnia. Magic is woven into the very foundations of Narnia. Animals talk, witches cast spells that turn those same animals into stone, and the spells are then broken with the breath of a lion (who is not tame). There is great enchantment in Narnia, along with adventure, fantasy, good, evil, and even death. Reading about this magical land is so fun that readers can forget that the stories of that secondary world contain truths about our primary world and how it operates. But reading fairy stories can allow gospel lessons and insights to “distil upon [our] soul[s] as the dews from heaven” (DC 121:45).

Writing for the New York Times in 1956, Lewis admits that he did not begin writing The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by asking himself how he “could say something about Christianity to children.” Instead, the story came to him one image at a time, as many stories do. He saw images of a faun, a sledge, and a lion in his mind. And then, only after he figured out what story they belonged to, did he decide to write it as a fairy story.

He made that choice because he saw how stories of Faërie “could steal past a certain inhibition which had paralyzed much of [his] own religion in childhood.” He asks:

“Why did one find it so hard to feel as one was told one ought to feel about God or about the sufferings of Christ? I thought the chief reason was that one was told one ought to. . . . But supposing that by casting all of these things into an imaginary world, stripping them of their stained-glass and Sunday school associations, one could make them for the first time appear in their real potency.”

Books have been written illuminating what the scriptures have to say about the Atonement, but fairy stories have some new ideas to bring to the conversation.

They offer us a realm full of enchantment, a potent form of art that brings with it, as Tolkien said in his lecture, “arresting strangeness” (pp. 59–60). Both Tolkien and Lewis delighted in the ways that enchantment connects us to the impossible and activates our minds to imagine things not present in the world. The fantastic magic of Faërie offers us metaphors for Atonement and salvation that are not accessible in reality. This allows a magic spell, an enchanted fruit, or a beast to lift the heavy weight of symbolism. Combined with the disarming power of fairy stories, these symbols and metaphors open up powerful possibilities for enlightenment.

The Project of this Series

In this series, I will use six fairy stories as springboards for discussing different ways we sometimes conceptualize Christ’s Atonement, referencing scriptures and the words of modern scholars and prophets as we go. After each fairy story, an essay will look at the metaphor the story uses for salvation and discuss what it can teach us about Atonement.

The Grimm Brother’s Snow White and Atonement as restoration

Jeanne-Marie LePrince de Beaumont’s Beauty and the Beast and Atonement as justification

Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market and Atonement as radical healing

Oscar Wilde’s The Selfish Giant and Atonement as reconciliation

Francis James Child’s Ballad 39A: Tam Lin and Atonement as love/rebirth

Hans Christian Andersen’s The Most Incredible Thing and Atonement as the most incredible thing

After we have studied these fairy stories, we will draw some final conclusions.

This series is not intended to present any kind of definitive interpretations of the stories it discusses. Readers will likely also see other themes in the stories, including themes of morality, politics, sexuality, gender, addiction, economics, and community. That’s okay. I intend to interpret these stories through one lens, but there are many other possible interpretations.

As I explore these metaphors, I am not trying to criticize and tear them down, seeking to expose all of the weaknesses in each one. I am also not interested in pitting the metaphors against each other in any kind of competition, narrowing the options until the best metaphor is found. It is only through looking at the metaphors together that we can begin to understand our subject. Tad Callister explains this in his book, The Infinite Atonement:

A person studying the Atonement is somewhat like the man who retreats to his mountain cabin to enjoy the scenery. If he looks out the window to the east, he will see the snow-capped peaks of the Rockies; but if he fails to examine the view on the west, he will miss the crimson-streaked sunset on the horizon; if he neglects the scene to the north, he will never see the shimmering emerald lake; and if he bypasses the window on the south, he will fail to witness the wild flowers in all their brilliant glory, dancing in the gentle mountain breeze. . . . So it is with Atonement (p. 1).

Each of the fairy stories and metaphors we look at will explore a single, infinitesimal part of the Atonement, but after we look at the pieces together, I hope that we will have a greater understanding of what Jesus Christ has done for us.

Importantly, these fairy stories and discussions don’t offer a list of rules or strict, capital-T truths to base a life on. Yes, I will operate from the Christian perspective that Jesus Christ is the way, the truth, and the life, and that no man can come to be restored, justified, healed, reconciled, or saved without him. But I do not intend to offer any other path to salvation, no breakdown of steps, no easy answers.

In 1 Timothy, Paul warns, “Neither give heed to fables . . . which minister questions, rather than godly edifying which is in faith” (1 Timothy 1:4), and this series isn’t intended to do so. I don’t want to encourage replacing scripture study with the study of fairy stories or suggest that these stories be taken as scripture. Nor is it my intention to offer up endless questions with no answers. The answer is, and always will be, Jesus Christ.

Here, we will explore, discuss, and edify—hike through the forested trails provided by these stories, find the good in each of them, and learn what we can.

And we will start with one of the most famous and beloved fairy stories of all time. The Grimm Brothers’ “Sneewittchen” or “Snow White.”

Chanel Earl is a writer—mostly of fiction—who currently teaches writing at Brigham Young University.

Original illustrations by Pauline Baynes (1922-2008) from The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950) by C. S. Lewis (1898-1963).

I’m looking forward to reading this series!🩷😊