Aporophobia

A response to the Mormonism and Mammon forum

The Spanish philosopher Adela Cortina argues that modern society is deeply riven by a hatred with no name: the hatred of the poor. She points out that there are daily crimes committed against the poor—crimes that if they were targeted at someone due to race or gender would be considered hate crimes—that we ignore because we blame the poor for their own condition. These can vary from the mean-spirited and disdainful, like the art gallery owner in San Francisco who was caught on video casually spraying a homeless woman with a hose to make her move, to the uncaring and structural, like the refusal to raise the federal minimum wage for over 15 years.

Cortina argues that part of the reason we are so cavalier about these kinds of hate crimes is because we have no name for them. As such, she argues we should call this aporophobia: the hatred or fear of the poor.

The world we live in is riddled with aporophobia that many don’t seem to see: our segregated neighborhoods, our segregated schools, the “problem” of homelessness, the “problem” of immigration, luxury goods, dollar stores. We allow the rich to get on first and sit in a special area of airplanes while the rest pack into the back. My town has a grocery store that is a level lower than dollar stores and discount stores: it sells expired and damaged goods (literally they told me, “stuff that fell out of trucks”).

Inequality is built into our cities. My parents live in a wealthy neighborhood made up of large houses with manicured lawns that is across the street from an impoverished trailer park. American urban and rural landscapes are a monument to aprophobia: gated communities next to impoverished ones. It is shocking, embarrassing, and cruel, and yet most people don’t even see it.

Confusion about support for capitalism from Christians is not new. It underlies Weber’s exploration of The Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism; Albert Hirshman’s bewilderment about “[h]ow did commercial, banking, and similar money-making pursuits become honorable at some point in the modern age after having stood condemned or despised as greed, love of lucre, and avarice for centuries past?”; and Marshall Sahlins’s eye-opening argument that “[t]he world's most primitive people [hunter-gatherers] have few possessions, but they are not poor. Poverty is not a certain small amount of goods, nor is it just a relation between means and ends; above all it is a relation between people. Poverty is a social status. As such it is the invention of civilization.” Consider the Osage chief Big Soldier’s 1820 critique of “Western Civilization:”

I see and admire your manner of living, your good warm houses, your extensive fields of corn, your gardens, your cows, oxen, workhouses, wagons, and a thousand machines that I know not the use of. I see that you are able to clothe yourselves, even from weeds and grass. In short, you even do almost what you choose. You are surrounded by slaves. Everything about you is in chains, and you are slaves yourselves. I fear if I should exchange my pursuits for yours, I too should become a slave.

Last year I published a book with BCC Press entitled: Meritocracy Mingled with Scripture. It was my attempt to think about the aporophobia I had long observed in Mormonism. I published an essay version of my argument in Wayfare entitled “The Dis-Grace-full Logic of Merit” that sparked a special series called “Mormonism and Mammon: A Wayfarer Symposium on Wealth and Merit.” I argued that meritocracy is a way of understanding money and inequality that turned them from vices, as they are portrayed in scripture, into supposed virtues. I argued that these inverted vices had infiltrated LDS culture, crowding out the order or logic of grace with the order or logic of money.

I’d like to now briefly respond to two of the other pieces published as a part of the symposium.

The first, Nathaniel Given’s “It is Better to Give,” argues among other things, that capitalism has gone a long way to decreasing poverty. This is one of the most common arguments offered by economists in response to the type of concerns made by Weber, Hirshman, Sahlins, etc. Yes, capitalism rejects traditional Christian morality, but the results are beneficial, we are told. The problem with this argument is that it is based on a very narrow understanding of poverty as primarily an economic phenomenon. But, as Sahlins and Big Soldier point out, there is much more to poverty and life than just material possessions and buying power. Poverty is a relationship with others. The modern poor may have a higher GDP than hunter-gatherers, but our modern aporophobia casts them down most cruelly. The claim that the poor are better off due to capitalism is a very dangerous claim when we treat poverty as a sociological or moral phenomenon instead of an economic one.

The second piece, “Why Jesus Exaggerates” by Jon Ogden, discusses his own initial personal inclination to condemn the rich based on some harsh scriptural passages. He argues we should understand that we should not treat these passages as literal, but as directional. In other words, the frustration Jesus expresses with the rich should not lead us to hate our rich acquaintances, but instead to point out the danger of their actions and encourage them to do better at caring for the poor. Ogden is correct that Jesus does exaggerate to make many of his points and that we need to be careful how we respond to such exaggerations. But there is also the problem of how some of Jesus’s exaggerations are dismissed or downplayed because they make us uncomfortable. In an aporophobic and meritocratic society, it is not surprising that Jesus’s condemnations of the rich are some of the first “exaggerations” to go. But read in the context of the intense suspicions of money and merchants in the ancient world, Jesus’s denunciations of the rich are not an outlier, but fairly standard.

I find it fascinating to see how Mormons respond to DC 49:20, which seems to indicate that one of, if not the source of sin, is inequality. This flies directly in the face of meritocracy and capitalism but was actually one of the basic moral principles of most of human existence. If Rabbi Abraham Heschel is correct, it was a fundamental principle of the Hebrew prophetic tradition.

I’m not sure we should downplay the plight of the poor nor the condemnation of the rich. I think when the scriptures repeatedly condemn the wealthy we should take it seriously. And when we don’t, we should think about why we don’t.

Justin Pack studies the political, social, moral and environmental implications of thoughtlessness, especially with regard to exploitation and alienation.

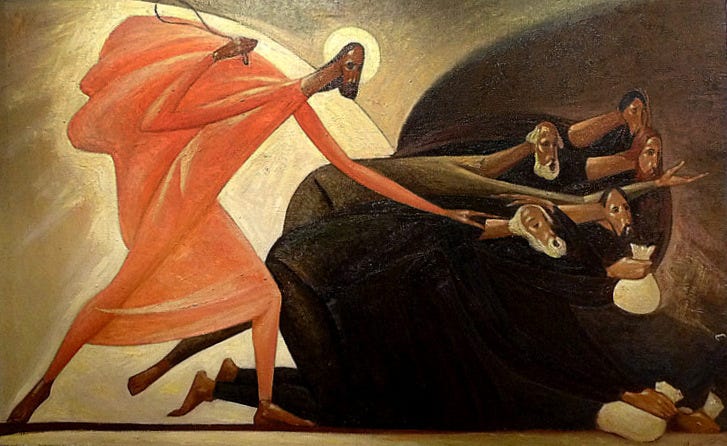

Art by Alexander Smirnov.