A Wider Spectrum of Color

On Seeing My Uncle Jay

My dad didn’t have any brothers, so he chose his own. A few people he recognized as kindred spirits became my uncles. There was Uncle Roy, who taught us how to play games like rock (where you hold very still to see who can pretend to be a rock the longest) and comatose (where you hold very still to see who can pretend to be in a coma for the longest). There was Uncle Rick, whose apartment had a wall full of music I remember looking over while he and my dad had serious conversations. And there was Uncle Jay—Jay Bell—who I keep thinking about lately.

Uncle Jay’s house was a wonder. It was bigger than I was used to, and nicer than I was used to, and he’d set it up just the way he wanted. He had these papasan chairs my brother and I could curl up in together, so round and magical and welcoming. Even though he was a grown-up with no kids of his own, he had the coolest stuffed animals. Upstairs there was a laundry chute that went straight down to the basement. That blew my mind. Not even the pneumatic tubes at the bank seemed so impressive.

He also had great taste in movies. It was at Uncle Jay’s house that I first watched It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. And I remember watching him get into long, animated talks with my parents after they’d watched a movie together. He’d get so into it, riffing like jazz, tossing off funny stories and wild ideas. Voraciously curious. Engaged with everything. He had thick glasses—I found out later he was legally blind—but his beard and glasses made his face so expressive as he and my parents would talk and talk while my siblings and I would hope they’d just keep talking so we wouldn’t have to leave yet and go home.

In 1995, when I was twelve, we moved across the country. Away from friends and relatives and adopted uncles. And so I missed the biggest change, which took place that same year, in Uncle Jay’s adult life.

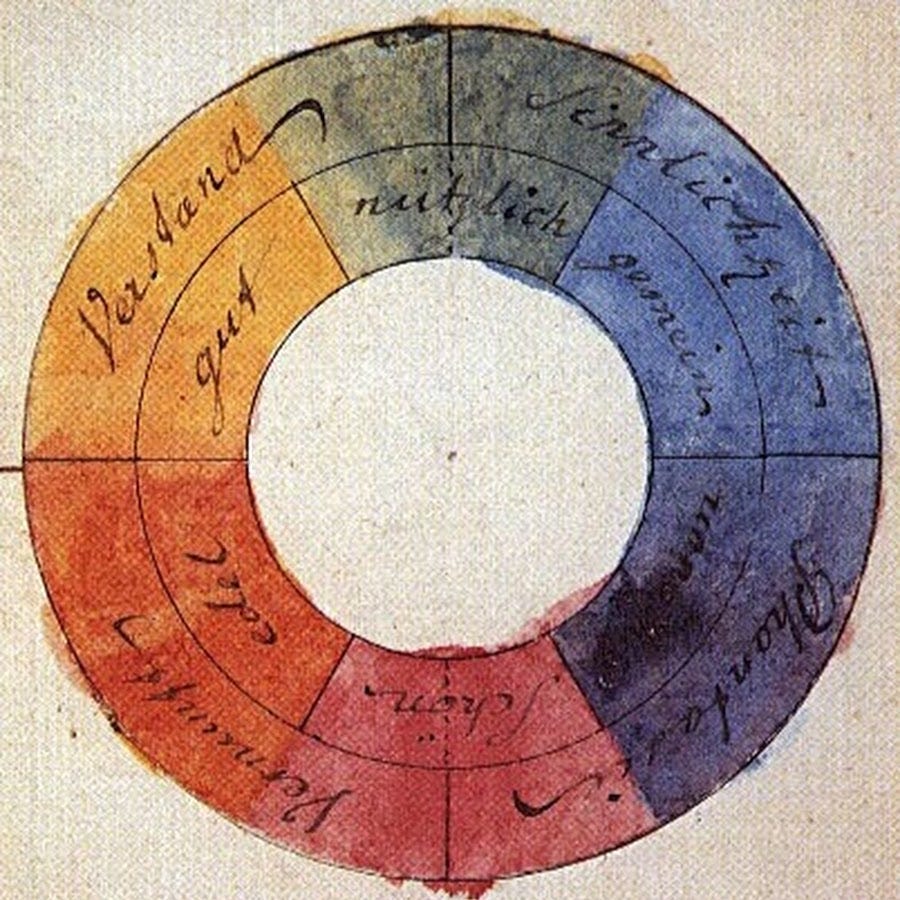

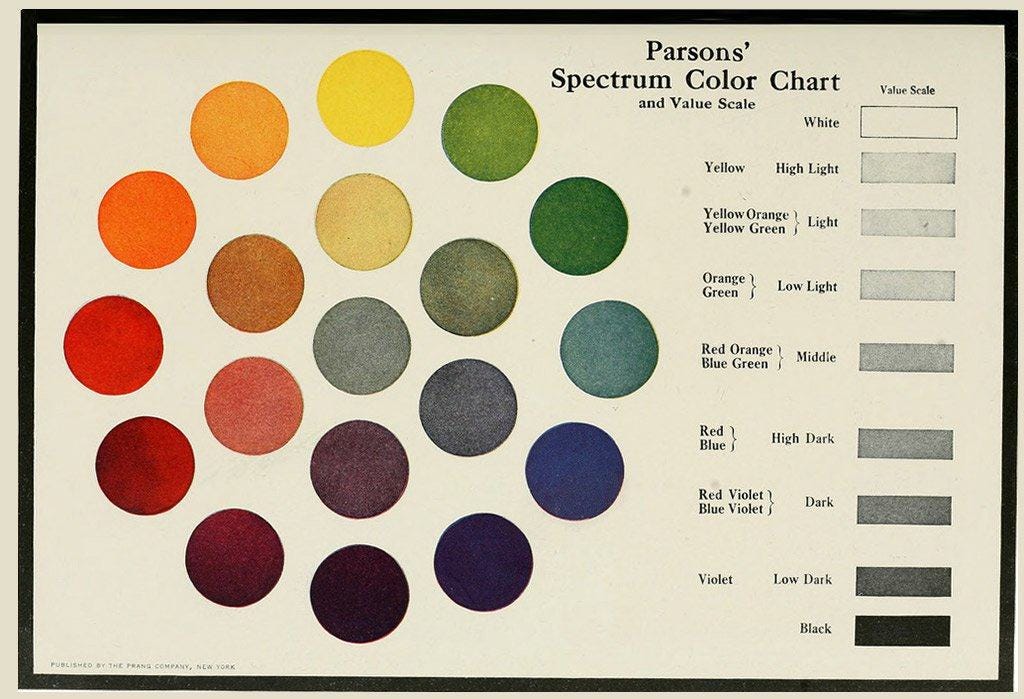

Let me pause here. Let me digress. Some things are too big to walk straight up to—you’ve got to meander first to get a sense of scale. Let’s approach 1995 by going back in time, a century and a half ago, when scholars noticed that words for color in the Iliad and the Odyssey don’t line up well with the way we think about color now. It’s a whole different world in those epics. Honey is described with the word chloros, the word that gave us chloroplasts and has typically meant green. The word porphyreos, which dictionaries translated as purple, is used to describe both the color of a storm cloud and the color of blood. The churning sea, famously, is called oinops, wine-dark. Then again, so are oxen. Nowhere in the entire epics is anything described as blue.

Nineteenth-century British commentators, trying to make sense of all this, wondered if Greeks in the Homeric age had physically different eyes. Later researchers have established that’s not the case: human eyes haven’t really changed over the course of recorded history. Languages, though, certainly have. In Sanskrit, Chinese, and Hebrew alike, blue is absent in the oldest texts. In general, the boundaries between colors are different: the earliest Greek philosopher to comment on the subject, for example, counted the rainbow as having four bands.

What’s happening? Because vision is a combination of what our eyes see and how our brains process it, it’s an open question what our ancestors actually saw. It’s possible that without words to distinguish them, yellows and greens blended into each other for them, and that the sky looks bluer to us because that’s the color we expect it to be. It’s also possible that our ancestors saw blue tones in visually the same way we do but just didn’t attach as much significance to them. As the comparison of sea to wine suggests, it may have been the light or dark shade rather than the blue hues that stood out as past minds interpreted the same wavelengths of light.

But if language shapes perception, perception also refines language. Over time, from the Aegean to the Ganges to the Yangtze, our ancestors developed more detailed vocabularies for color. The oldest written usage of a term to describe blue comes from ancient Egyptian, maybe because that’s where the first blue dyes were made. I can imagine some weaver woman or craftsman studying the new dye and beginning to piece different experiences together, the way clues come together at the end of a good mystery. I wonder what it would’ve felt like to be the first person in a civilization to look at waves, at the space between clouds, at rare berries and at exotic stones, and give a name to the look they all shared. What would it feel like to discover a color that had always been there, just waiting to be articulated and defined?

I wonder, when I think of my Uncle Jay, if that’s what it was like for him in 1995. We call it coming out now when a man publicly identifies himself as being attracted to other men, or a woman to other women. For so many people, though, there seems to be a stage first when feelings come into focus. Longings, emotions, sensibilities coalescing, constellating to reveal a pattern that was waiting there. Like an eye tuning in to name blue for the first time.

As Jay later told the story, a quote from Spencer W. Kimball in a Church manual was the catalyst. He was teaching in Young Men at the time, and there was a passage in the manual about homosexuality, and he found himself wondering whether that word had something to do with his own internal reality. For a while, he circled around the concept. Some things are too big to walk straight up to: you’ve got to meander first. He visited a group for the parents of gay Latter-day Saint youth, trying to get a sense of what it might mean to be supportive to someone in that situation. Then he worked up the courage to go to his first Affirmation meeting. The thought of being around so many other gay men at once made him feel self-conscious. He said that he went to that first meeting feeling worried that the other attendees would only be interested in his body—and came home disappointed that no one was!

It didn’t matter. More than we want to be desired, we want to be understood. All those men who weren’t interested in his body recognized something in his psyche that had long gone unnamed.

Discovering that seed of a sexual identity was only one part of the process, though. Once he’d seen it, he wanted to make something of it. Adopting a public gay identity was an ongoing exploration. Like so many others before and since, he was an immigrant in that culture, trying to cultivate new ways of being in his new world.

Since it was the 1990s, that meant experimenting with a certain flamboyance. I heard one of his friends reminisce later about a noveau-gay Jay playing with his walk. Just trying to get comfortable in his body by trying out new ways to move. One afternoon, they’d stopped to pick up a cake, and this friend watched from across the parking lot as Jay balanced it with an exaggerated elegance on an open palm, then proceeded to sashay across the parking lot—right into the open front seat of the wrong car.

We all try to create connections between who we are on the inside and how we present ourselves to others. I don’t think the “self” is just a bundle of raw, unprocessed feelings. My sense of self is a combination of interior and exterior, of subjectivity and sociality. I don’t expect to just “find myself” someday: I’m constantly shaping my sense of self to link my own experience in different ways to other people and other aspects of the world around me. If I’m honest, I am not sure I can ever be perfectly true to myself. After all, if you ask me who I am, I’m going to answer in language. And language is powerful, but it’s also tricky, inevitably emphasizing some connections at the expense of others. If I call the sea “blue” instead of “wine-dark,” am I losing what it has in common with the muscle rippling across an ox’s back? If I call the sky blue like the sea, am I losing some emphasis on its light? As someone who has spent a lot of time finding the right words for experience, I can’t even imagine packing all I am—all anyone is—into a neat package of words. The human soul is too big to fit on a human tongue.

In this world, maybe a self is not a truth waiting to be discovered so much as a constant construction zone. Like any road, the way I express myself can link me to other people and things, but there are always going to be some potholes and orange cones along the way. It’s okay if one day you run into something unexpected and honk! I am sure there were people who didn’t know what to do with Jay as he was sorting out a new sense of self. Like, for example, the woman sitting in the car he mistakenly sashayed his way into.

I feel, though, that people in a missionary faith have tools that could help us understand.

Consider a religious conversion. I believe firmly that some people are hardwired for spiritual longing. It’s just a part of their experience, which wells up from deep down. In the former East Germany, where I served my mission, schools had taught in a matter-of-fact way that there is no God, and the state had done its best to wipe out belief. And yet in different cities in that country, I met two different people—each raised atheists—who had seen a prayer on television once and immediately recognized it as something they’d always wanted. I met several other people who told me that belief in God was pure nonsense—but who also told me they did believe in guardian angels because they’d had experiences they couldn’t explain to themselves in any other way. In some hearts, then, the seed of faith predates the language of religion. Just like there’s an experience of color that predates the vocabulary. Just like there are internal feelings that predate any self-organization of those feelings into language of sexual orientation.

The internal seed of faith isn’t the whole story, though. Being introduced to a religion often leads to observable change. An investigator may recognize God’s hand in their prior life, leading them toward the gospel, but friends and family are more likely to notice when they disappear on Sunday or quit drinking or when their sexual attitudes or behaviors shift. For the convert, those visible changes in habits, language, and worldview are important parts of a developing religious self. For friends and family, though, those changes can be disorienting. Even if my child converted to a religion I admire and respect, I would need some time to sort through my own expectations and make peace with their decision. On my mission, friends and families of converts typically lacked the luxury of previous goodwill toward Latter-day Saint faith. In that environment, there were negative stereotypes about religion generally and especially negative stereotypes about Latter-day Saints. It can be hard for people to watch a conversion when they’re not sure if their loved one is joining a cult, if they’re making a terrible mistake.

I’ve been to baptisms where loved ones came to celebrate, happy only that a person they cared about was happy. I’ve been to baptisms where loved ones came to be supportive, still feeling nervous about the wisdom of the decision but willing to make a show of respect for a person they cared about. I’ve been to baptisms where loved ones didn’t come, feeling that to do so would condone a choice and worldview they could not accept. These are all human reactions.

Up until the late 1990s, my Uncle Jay had spent his life as an active Latter-day Saint. He’d gone to BYU, had taught in the Missionary Training Center. I’m sure that some people who saw him adopting a gay public persona thought he was on the wrong path. I’m sure some people in his life felt like he was making a terrible mistake when he decided to leave the Church in favor of, as he put it, “a religion of one.”

I never really got time to figure out how I felt. I got so little time with him. With our move, we’d slipped further outward in each other’s consciousnesses. I didn’t see the everyday changes a friend in Utah would have. The last time I saw him was when we arranged to meet up for lunch while I was on the way to the MTC for my mission. I’d been set apart before flying out from Ohio, so my grandpa came with me as my companion as the three of us sat down for Navajo tacos together. I recognized the same Uncle Jay, with the same warmth, the same restless curiosity. I was glad we got to talk.

One day, while I was off in Germany, listening to atheists tell me stories of their guardian angels, Jay went to cross a street. He couldn’t see a car coming. The driver didn’t see him soon enough. That body of his, that beautiful body God made, that body he’d worked to get comfortable in—that body broke.

And his spirit rose to another world.

What happens there? We focus so much on enduring to the end in orthodoxy that we don’t always know how to process the loss of someone who left the Church.

One interpretation of the vision Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon recorded in Doctrine and Covenants 76 is that the average person who drifted out of the faith will be received into a brilliant heaven, finding rest in Jesus’s arms and dwelling forever in his presence—but without a celestial degree of glory. It strikes me, writing this, that it’s a little odd that this prospect is what keeps many Latter-day Saint parents up at night, wringing hands over their children who didn’t keep expectations about faith or life choices. What if all those children rise to is a heavenly bliss beyond all human description? How disappointing.

Maybe what we fear is not the hell we don’t believe in, or the terrestrial glory we teach, so much as children not growing up to be all we want them to be. Sometimes the spiritual appeal of the celestial kingdom gets its wires crossed with the more worldly hope that our children will live out our own vision of success. That is human. The longing for a perfect family photo with matching clothes and beliefs.

Fortunately, the sorrow that comes with broken expectations is thoroughly treatable. It’s OK to mourn a lost story for a night, if you’re willing to find a new one in the morning. Jay Bell’s brief Deseret News obituary, for example, likely written by Latter-day Saint family members, mentions his missionary service and also his research on gay experience, which it positions as a contribution to American diversity. Our earthly worries over unconventional children can be eased simply by learning to appreciate what they do rather than dwelling on what they don’t.

If it’s really the difference between heavens we’re worried about, though, a person like Jay winding up locked in terrestrial glory is hardly the most likely scriptural possibility. Another model, taken from Doctrine and Covenants 88, is that there is no space without a kingdom, and no kingdom without space. In that view, we don’t need to imagine souls landing forever on the other side of a border between heavens because the combination of their life experience and the era in which they lived made it more challenging for them to stay in the Church. We can trust that light clings to light, and mercy to mercy. If the vision of three kingdoms is a simplified model (like Bohr’s version of the atom) rather than a reality with borders and checkpoints, then what I expect for my Uncle Jay is that his willingness to embrace light—any sort of light—in this life will open the door to a continued outpouring in the next. There may be truths and ordinances that shine brighter for him when the dross has passed away. I suspect we’ll all find that we rejected one light or another in this life because it came to us in a perplexing package. If we missed one truth by reaching for another, there will be time and tools to set things right. An outpouring with an exclamation point, brighter and brighter until the perfect day.

What happens in that world above with that part of him which we called orientation? Scripture is silent. Scripture doesn’t even ask that question. I can understand why many people now do. I hope we get compelling answers in the future. I can understand how a question like that, about the meaning of a deep part of himself, might’ve mattered to Jay. It doesn’t feel like it’s my place to make any claim, though.

How exactly divine light might refine and transform each of us is a mystery beyond what I know. I don’t believe any of the experiences God gives us go to waste, but I don’t know what form they take either. If I am telling the truth in a spirit of radical humility, I don’t actually know which of the yearnings and loyalties Jay felt over the course of his life—toward his faith, our history, toward men who loved other men—were a distraction, which were a shadow of something different to come, and which were willed for God’s glory.

In this life, some of us walk in the ways of our fathers; some to the beat of a different drummer. You can ask how we’ll walk in the next life, but will a question like that even make sense when we can fly?

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

Find more Wayfare content on the LGBTQ+ experience in faith communities here.

I don’t want to spend all day trying to make a comment brilliant enough to match this wonderful article — I guess I don’t even have to— so I will just say thank you very much.

This offers a lovely description of the self, one that makes perfect sense to me. We are all contradictions wrapped in enigmas and one of the tasks of life is to come to know ourselves and each other better as we move through life. Thank you, James, for the thoughtful essay.