A Psychedelic Primer for the Latter-day Saint

I first encountered psychedelics at a ketamine-assisted psychotherapy clinic in Utah, not knowing what they were. After antidepressants had failed me and therapy had stalled out, psychedelics quite literally saved my life. This essay comes as a direct result of these experiences. Here, I’ll give just a brief glimpse into psychedelics, their history, and how they are being used to help people with mental illness seek greater well-being in their life.

Since those first experiences of mine, I’ve devoted much of my time and work to understanding how these substances help others and how they have been used throughout history. I went to work as a research assistant at a ketamine clinic and decided to focus my graduate work on the nature of healing in psychedelic experiences. This was just prior to psychedelics really entering the mainstream after the publication of Michael Pollan’s book How to Change Your Mind. I’ve since written curriculum to train psychedelic-assisted psychotherapists, taught courses on psychedelics, and done extensive research making sense of the experiences people have and on psychedelics’ religious use.

A Brief History of Psychedelics in the Western World

For the unfamiliar, psychedelics is an umbrella terms for a variety of substances, each with unique experiences and effects including the well known psilocybin, LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide), DMT (Dimethyltryptamine), MDMA (Methylenedioxymethamphetamine), ketamine, and ayahuasca. A broader term is a “psychoactive” substance, a substance that affects changes in the mind. This includes a much broader class of plants, animals, fungi, and human-synthesized molecules.

Psychoactive substances have been used throughout history in nearly every culture across the globe dating back thousands of years. For many, these substances played a central role in their religious worship and in their healing practices. Psychoactives such as henbane, opium, cannabis, ergot, and others have been found in archeological sites throughout the territory of ancient Greece dating as far back as 1500 BC and used for both religious and medicinal purposes. Similar sites have been found throughout ancient Egypt, Israel, and all over Europe, some dating as far back as 6000 BC. There is continuous record of them being used from that time through to the present day.

South, Central, and North America have a similar history of psychoactive use for medicinal and healing purposes through the present day. Psychoactive substances like psilocybin, peyote, ayahuasca, tobacco, and datura, among others, were used for spiritual purposes, such as rituals and rites of passage, as well as to aid in the diagnostics and treatment of physical, mental, and spiritual ailments. For many cultures that utilized these substances, there wasn’t a distinction between healing and spirituality, and there still isn’t among many indigenous tribes.

In the 1800s, some Western scientists, such as Humphry Davy and Jacques-Joseph Moreau de Tours, became interested in how substances like nitrous oxide and cannabis could be used to understand and possibly treat mental illnesses. But the first major wave of modern psychedelic research began with the serendipitous discovery of LSD by Albert Hofmann in 1938. During the 1940s and 50s, following the ideas of their predecessors, researchers thought LSD could be a potent tool to mimic experiences of psychosis to help understand the causes of mental disorders. Because a chemical could produce similar symptoms seen in mental disorders, researchers began to look into a possible neurochemical basis for mental disorders, which were previously understood to be simply psychological in origin.

There was a frenzy of research and publications during the 1960s that touted psychedelics as a miracle cure for mental disorders. Thousands of studies were performed in mental health clinics across the United States and Europe. During this time many psychedelics, particularly psilocybin and LSD, became popular among the general population. For a variety of reasons there was an international ban on psychedelics in 1971 that was pushed through the United Nations at the behest of the United States as part of the now-failed “War on Drugs.” These substances persisted in the underground and remained the silent object of study of a few researchers in Europe.

The large-scale revival of modern interest in psychedelics by the scientific community began with work by Rick Strassman on DMT in the early 2000s, but really took off with the publication of Roland Griffiths and colleagues’ 2006 study “Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance.” Since the publication of that paper, there have been thousands of new studies done on psychedelics, their effect on the brain, and how they might aid in the treatment of mental disorders.

Contemporary Psychedelic Research for Mental Health

The recent surge of interest and study surrounding psychedelics has coalesced around their potential benefits for mental and emotional health. Recent research has suggested that these substances can be beneficial for a whole swath of mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, PTSD, eating disorders, addiction, OCD, and others.

Within clinical trials and in places psychedelics are legalized, such as Oregon, the typical psilocybin or MDMA experience for treatment of a mental disorder consists of a patient lying on a bed, couch, or mat with an eye mask and headphones on. Typically there is at least one therapist or guide present in the room to support the patient during the experience. The majority of the experience is guided by music and happens internally within the patient. At the end of the 6-8 hour session, the patient debriefs with the therapist, their physiological state is checked, and they are sent home, usually with a follow-up appointment for integration in the following days.

There are, however, a vast diversity of non-academic communities who create their own ceremonies utilizing these substances. Some have religious approaches that include singing, ritual movement, and facilitated journeys. Some focus on movement and yoga, while others are guided experiences in nature, and many move between different modalities of healing during the experience. All these practices can provide benefits to participants, provided they are facilitated by a carefully selected and qualified facilitator (a common term for one who guides a psychedelic experience). Oregon, the first state to legalize psilocybin, has developed standards for training these facilitators, as have major psychedelic research organizations across the globe. These practices provide community-sourced anecdotal data that can help inform research done by clinicians involved in official academic studies.

One of the more interesting empirical theories for how psychedelics aid healing comes from neuroscientists Robin Carhart-Harris and Karl Friston’s REBUS (RElaxed Beliefs Under pSychedelics) theory. They suggest that the human brain builds models of the world in an effort to reduce uncertainty and explain events occurring around us. Carhart-Harris and Friston argue that the brain functions in a Bayesian manner, meaning it is constantly updating belief systems as more evidence supports specific models for understanding the world. Over time these models, or priors, become stronger and more rigid—they have more weight to them.

The models our brain constructs, however useful, are not always accurate. For example, an individual with depression might have recurring thoughts that the future is hopeless. Any indication that this could indeed be the case becomes more and more salient and works to strengthen this model over time. The rigid, low-entropy mental state that results can be extremely difficult to overcome because the brain wants certainty, and the perceptions that have built up over time, called the priors, have become too strong. Psychedelics introduce entropy into the system, leveling the playing field.

A useful analogy for how this works is a ski slope. The more individuals ski down a hill, the more a path is carved out in the snow. This path becomes more defined and deep, making it difficult to change course while on the path. Our models, or priors, are this path. They are difficult to escape. Psychedelics are like a fresh snow storm, blanketing the old paths and making it possible to carve out a new path.

Recent research has suggested that psychedelics increase the brain’s neuroplasticity for a short time during and after the experience. Neuroplasticity is the capacity of neural networks within the brain to change, reorganize, and grow. Essentially, the brain has the ability to be rewired and change how it has functioned previously. With proper care, support, and integration, psychedelics can open a “window of change” within an individual that allows for a change in thought patterns, habits, and ways of viewing the world.

In a clinical trial that utilized psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression, a patient reported that “It [the psilocybin session] was like a holiday away from the prison of my brain, I was a ball of energy bouncing around the planet, I felt free, carefree, re-energised. . . I felt my brain was rebooted, I had the mental agility to overcome problems.” Others reported having clear minds, the fog of depression lifting, and escaping the depressive loops that had plagued them.

These experiences have been beneficial for people suffering from PTSD, allowing for a transformation of the traumatic experiences; addiction, helping individuals break free from various addictions including alcohol, tobacco, and other substances; and depression, enabling sufferers to break the thought patterns that hold them captive. The blanket of fresh snow that psychedelics create allows for new paths to be carved, offering an unparalleled opportunity to help individuals suffering from mental disorders. For many, psychedelic-assisted therapy offers a much-needed respite from the pain and a glimpse of hope towards healing.

The Role of the Psychedelic Experience in Healing

While neuroplasticity offers a potential physiological explanation for the benefits of psychedelics, many people report that it is the experience of a psychedelic session itself that is the catalyst for healing. Common features of the experience that people connect with healing include: insights into self-identity and behavior; experiences of interconnectedness; feelings of awe, wonder, and curiosity; and a deep sense of love and connection to other people, nature, and the divine.

For example, in one clinical trial for cancer patients, Mike, a father of three daughters, described how, after his psilocybin session, he was able to more fully understand his daughters and the anxieties and fears they were struggling with. He described his experience:

Bit by bit, my daughters were turning into these radiant beings, cleansed of all these fears. It was incredibly emotional, because it was something I have, as their father, long known, but it’s a very great pain when you see your children being victimized by fears and . . . to see these beautiful beings not realizing their essence.

After this experience, he related the vision to one of his daughters, “and she started crying. She came over, and she hugged me and was just holding onto me, and I knew that I had reached the place that I knew I could reach in her.” Because of his experience he could empathize more fully with his daughters.

Another example comes from an individual who participated in a study of psilocybin for treatment of tobacco addiction. They said of their experience,

I . . . had the sense of everything being connected. And [the psilocybin session] reinforced that, very strongly . . . [If I were to smoke] I would be a polluter . . . ashtrays and butts all over the place, and you’re causing harm to other people’s health as well. And so you were re-looking at your place in the universe and what you were doing to help or hinder it. The universe as such. And by smoking, you wouldn’t be helping.

Notably, this participant had zero lapses in smoking after their session, which they attributed to the sense of interconnection they experienced during the session.

These are just two of countless stories of healing and growth that individuals experienced from their psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy sessions. Research suggests the benefits aren’t limited exclusively to healing mental illness. In a study done on individuals who had undergone a psychedelic experience utilizing ayahuasca, users reported a series of persisting positive changes:

A change in health behaviors including diet. Participants also often gave up alcohol or cigarettes, enhanced clarity, recognition, and sensibility, increased physical well-being, energy, power, and strength, better coping with problems and ‘daily hassles,’ confidence and tranquility, a renewed sense of happiness, love, and joy, a change of life orientation sometimes including a strive for non-materialistic values, improved social competences.

These benefits have been sustained over time and found in many clinical trials to date. All of this recent research is absolutely a cause for excitement. However, it must of course be said that while these appear to be “miracle” cures, they are not for everyone. They don’t provide instant and lasting cures for all. Even when they do provide healing, the lasting benefits still require continuous effort and striving for health. Patients should always be screened to find out whether psychedelics are appropriate for them to try in light of their health and family history. As with many substances, there are risks associated with the use of psychedelics. We’re only at the beginning of the search to better understand these substances. While they’ve been used throughout history and some of the insights from the past have survived, much has been lost due to colonization. There is still much to learn regarding how to best utilize these substances for the benefit of all those who suffer or desire to heal.

One of the key facets of psychedelic healing is the integration process. Most clinicians and psychedelic facilitators require an individual to return for a series of integration sessions after the experience. This consists of a variety of modalities, whether guided meditations, talk therapy, working through difficult emotions that may have been brought up, or helping them make sense of the experience they had. For many, especially first-time experiencers, the experiences undergone while using psychedelics come as an ontological shock, meaning their models of the world, what is real, and what is possible are challenged. The apparent interconnection of the world experienced by some of the individuals mentioned above stands in stark contrast to the individualism that pervades Western society today.

A key aspect of integrating any emotionally-charged experience, whether a psychedelic experience, the loss of a loved one, or even a peak experience such as successfully executing a musical performance, is being able to share that experience with a loved one. By sharing, they can process the experiences and ensure they retain beneficial changes. A question all psychedelic facilitators should ask is whether individuals have robust social support systems of friends or family, and if the individual feels comfortable talking to them about their experiences, whether positive or challenging. This doesn’t require any special knowledge or skills on the part of friends and family, merely curiosity and willingness to listen. It’s part of comforting those who need comfort.

Concluding Thoughts

Psychedelics offer an opportunity for healing for those who suffer from treatment-resistant mental disorders or who have otherwise struggled to find any respite from their suffering. For myself and many I know, they have helped us heal. Beyond that, the experiences facilitate a deeper understanding of many of the blessings life has to offer and new ways of perceiving the world and our lives. New research comes out every day, and I’m optimistic that we’ll figure out how to best utilize these substances.

Alex Criddle is a philosopher interested in consciousness, mental illness, psychedelics, mysticism, occult, birds, permaculture.

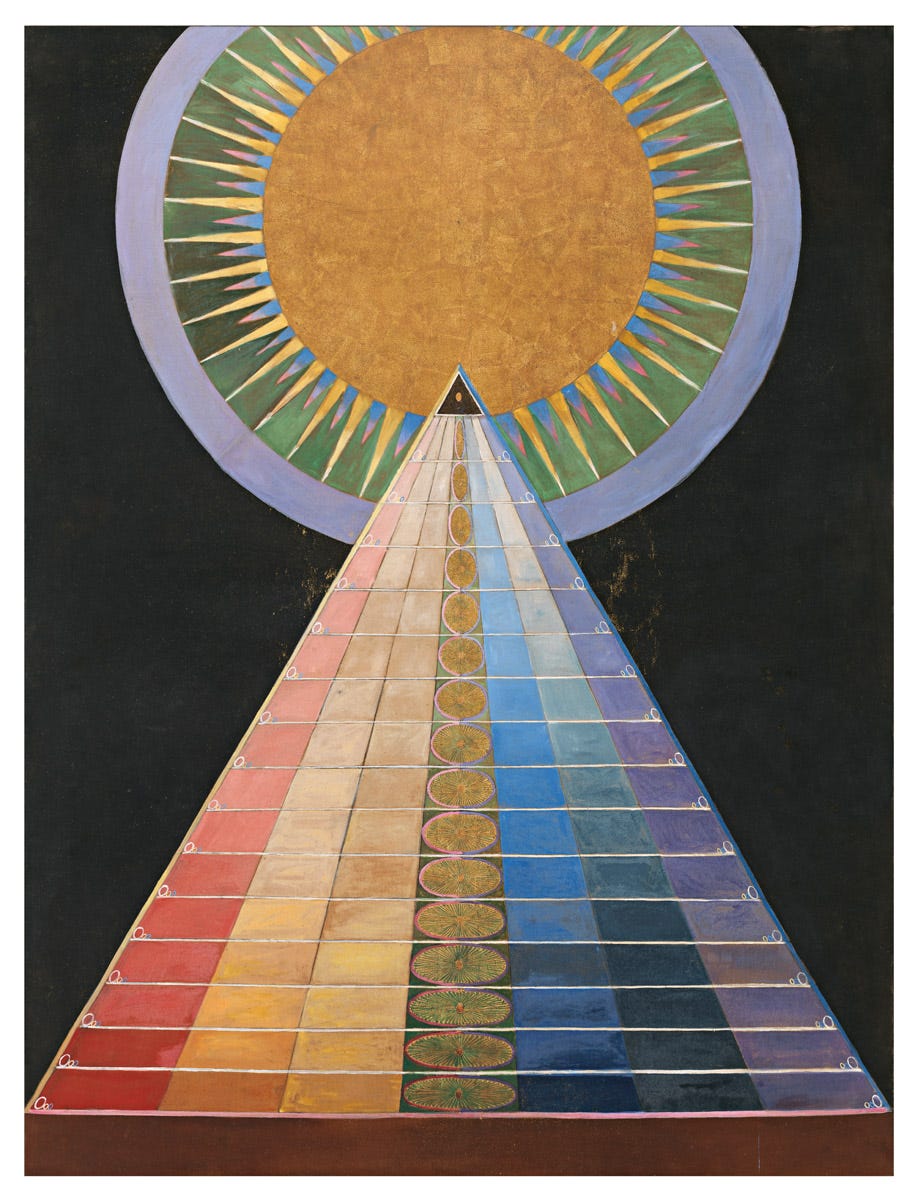

Art by Hilma Af Klint.