A Grief Shared

I was eighteen when my father died. I’d be exaggerating to say I never knew him. My mom made him leave when I was twelve, and I saw him a half dozen times between his departure and his death six years later. But he’d actually been thriving in my early childhood in Helena, Montana. He had a job then where he felt valued, kids were accumulating on the familiar pace of five per decade, and we had lower-middle-class financial stability. I remember driving in a giant Ford station wagon, delivering newspapers in the freezing pre-dawn darkness, watching him cry when particularly beautiful music played on the classical music station. He sang with a loud baritone that I inherited, and reliable pitch, which I did not. I relished his pleasure in throwing Sunday waffle parties for friends and neighbors. I also remember the stories he made up in the telling, in which we children were the main characters. I no longer remember my name in that fantasy world, other than the sibilant alliteration—savvy Sam or super Sam or the like—but I remember that the protagonist of the story cycle was a boy named Polly Push. The boy got that name because his favorite words were a request that his older sister Polly push him on the swing.

With substantial effort, I could uncover other memories, but such are the accessible highlights of our relationship. We were reconciled just before he died as part of the miracle of my late-adolescent conversion. The reconciliation came to be through a letter I received from him in mid-November in my first year of college. By late December, we were with Dad at LDS Hospital, his belly full of protein-rich fluid the color of beer. The hepatitis he got from the kidney transplant that replaced the organs ruined by his poorly managed diabetes, had driven his liver to cirrhosis. He joked, thinly, that he was pregnant and expecting twins any day. I remember his sallow, yellowing skin and the horrible thin mustache. It would be a half dozen years before I would understand, medically, why he looked as he did: the typical appearance of someone dying of liver failure. What I knew at the time was that Grandpa said Dad was dying, so I took my siblings in to say goodbye during my Christmas break. He died about a week later: cardiac arrest during dialysis. CPR could not restart his heart, so the team stopped their rhythmic compression of his chest.

I was back at college by the day my father died, in the middle of a Boston winter. I hugged my closest friend at the time, an atheist Jewish woman named Amy, in the quiet leafiness of Harvard Yard. She wept more than I did. She found herself discomfited by the finality of death, imagining what it would mean for her parents to lapse entirely from existence. I was aglow with faith in God, true, but I also didn’t have much of a connection to my father as a person. He had always been a startling absence in my life. The fact that the cause of absence was death now, rather than madness or my anger, was immaterial. I suppose I did mourn his death, but that mourning started long before he died and faded quickly once he was safely on the other side. What grief I experienced had to do with my vision of what ought to have been. I was experiencing a generic form of baleful deprivation. I was a fatherless boy. It was the figure of a father that was missing rather than anything specific to the man who just breathed his last on a dialysis machine at LDS Hospital. Such was my early grief.

Later in adulthood, I encountered a new form of grief in the intensive care unit. That’s where I practice medicine; I’ve been working in ICUs for about fifteen years now, drawn to them even before I graduated medical school. They are my home territory, my professional habitat. There is nothing quite like the drama of doing strenuous battle with death. The weapons are life support systems, our wits, and our hearts. The stakes could not be higher.

The statistics say that about one in eight ICU patients will die within the month. It’s that severity of illness that justifies the extra attention from nurses, doctors, and therapists. That statistic is even a bit optimistic because many of the survivors are people who are in and out of the ICU before we can even blink. It’s probably about a quarter or a third of patients we really get to know who will die. We are immersed in death in that place. Without us, many more would die. But even when we try our hardest, people still die. It’s biology. So I’ve made peace with it. I have to manage the grief both to provide excellent medical care and to be a decent human being. It’s something I’ve taught myself to do. I’m pretty good at it. The point is to give people some guidance, treat them well, honor the dying, and grieve in controlled amounts. To grieve every death in the ICU as if it were the death of an intimate is too much. It just is. You’d break. So you mourn a tiny bit with each death, while allowing the families to do the primary work of grieving. With John Donne, you hear the bell tolling and realize that it is calling to each of us at some basic level. But today the bell does not ring for you or your beloved. Grieve too much, and you will lose your mind. Grieve too little, and you will lose your soul. Such is the balance of life and death in the ICU.

By the time I had arrived at middle age, I was well acquainted with grief. I had even written a couple of books about death and the care of patients with life-threatening illness. I was, as they say, a published expert.

But all that counts for little when your wife loses her eye and then her whole body to a rare melanoma over the course of a bittersweet decade of life lived in the shadow of death. I can see why Damocles gave up after a day of living under the dangling sword. The grief that comes from the death of a beloved takes your breath away, clouds your vision, squeezes your heart, and a million other terrible things. It is also sacred, expressing the depth of the bond that has been disrupted. It is seeing clearer than we have ever seen before, even as we are blinded by the suffocating mists of anguish. Both things, as my Kate of blessed memory would say, are true of grief.

The love and the pain aren’t the only polarity that grief mediates. There is also, inexorably, the question of individuals and communities.

One-year-and-a-lifetime ago, we are seated around the kitchen table, an ancient Quebecois butterfly table. My laptop balances on the windowsill, behind which stands the floral menagerie-cum-potager that my wife accumulated over the decade we have spent in this house. She loves beautiful things and old things. We, also beloved, sit in the midst of both.

Our oldest child, just back from her first year of college, has joined family therapy for our youngest, who is at a therapeutic boarding school in southern Utah. Therapy is by video conference, and we pivot the laptop camera from face to face, like a low-budget documentary. We’re far enough along in her therapy now that it’s okay to talk about death. Her mother’s death. My Kate’s death.

For years, that lethal portent has been the fact too horrible to say out loud for our struggling daughter. Kate grimaces a little with the pain of shifting bony matter inside the vertebral body that we will soon discover is being eaten by her cancer. But also with the reality that she does not love to dwell on the physical and emotional tragedy that is unfolding month by month. Cancer is no simple thing. Sometimes it is hard to say its name aloud, and sometimes it is the needed thing.

“When I was at school a girl in my dorm was talking about it,” our oldest explains. “She said it’s like having a mission call. Mom is called to serve in the afterlife. That made sense to me. It was really comforting.” The youngest nods, trying on the idea that perhaps our loss will be a bit more tolerable if in fact we know Kate will be doing good things with her time away from us. The story even makes a little sense to me—Kate had been away in Paris for a final visit a couple weeks earlier, and I didn’t miss her as much then because I knew she was in a place she loved. Maybe heaven will be a bit like Paris. We’ll be lonely without her, but confident that she is flourishing.

Even so, I wince. We’ve heard that story before, many times. Kate and I wrote an essay a decade ago that began with an uneasy engagement of the young-adult novel Charly. That titular woman, Charly Riley, is another mother dying of cancer. The novelist paints her afterlife as concrete, busy, and happy in a way meant to put her widowing husband at ease. Kate and I weren’t the first to hold Charly at an awkward distance. In a book on Mormon history and culture, Lester Bush described a young woman of his acquaintance who wrote a letter to be shared at her funeral, forbidding any reassurance that she was serving an afterlife mission. In my paraphrase, that dying mother was asking an urgent, rhetorical question. Why on earth would you say that dead people they’ve never met are more important to me than my children? My calling is to be mother to these children, not to dead strangers. Kate and I played along with Bush and his friend in that old essay of ours. We knew how absurd the traditional story was. But here is that sorry story from Charly and Mormon lore, and it is actively helping our oldest daughter deal with the coming death of her mother.

By then I might have known better than to doubt platitudes and a positive attitude. Honestly, that’s been my professional experience in the intensive care unit. I’m often called by human decency to try to say something helpful in the face of an untimely death. Maybe a decade ago, I noticed a louder consensus among thoughtful liberals (my tribe all these years) that the best and perhaps only appropriate response to grief is to emphasize the extent of the tragedy. People shouldn’t rush to explain or place the tragedy into meaningful context. They should instead resonate with the pain. Full stop.

The old way of focusing on the positive, these critics explained, left people feeling alone and misunderstood. Buried in platitudes rather than succor, they had to struggle through more than their grief. After hearing a particularly passionate exposition of the idea, I decided to give it a try. I did so for about six months. But I noticed that while a few people clearly resonated with the new approach, most stared at me in perplexity. Why would I refuse to reach for a shared language of meaning or reassurance, they seemed to ask, when I’d been around death before? I wasn’t a novice, so why was I acting like one? Saying that I had read it on the internet, however true, was not the right answer.

I ultimately abandoned that guiding principle, because it wasn’t working. I spend more time now trying to get a sense for people, to hear what kind of language they’re using, what questions they have. I talk less. And, when I get the sense that such words will be most useful to the people I’m talking to, I say positive and optimistic things. I even use platitudes. Not because I’m denying the grief. God forbid! But because I am meeting the grief with the power of human community and hope. I’m certain I get it wrong sometimes. But better some earnest missteps, in my view, than being the flag bearer for an ideology that grossly misreads most people. I’m wrong less often now that I’m open to more than emotional resonance, no longer merely echoing back well-intended darkness for darkness.

I get why some good people believe that the only response to grief must be to steadfastly acknowledge the depth of tragedy. Much of modern philosophy teaches that life is a meaningless accident. So instead of offering meaning, our job is to stare together at unmeaning. This philosophy plays more and more in public rhetoric these last decades. We need to know that context.

To be clear, this approach isn’t entirely wrongheaded. There is something sacred about holding hands in the face of inscrutable suffering. For some of us, the shared acknowledgment of our inability to make sense of something vast can be a great reassurance. When the situation calls for it, as it sometimes does, we should gather together against a baffling misery with nothing but the fact of our loving presence. But we would do well to remember that we can stand together and see true meaning. The two are not mutually exclusive.

The more I’ve stared at these questions from the various sides, the more I think that this new trope—resonate with tragedy and nothing else—is a mandate to treat everyone who grieves as if they were mentally ill. On average, people struggling with mental illness, particularly in our modern cultural moment, crave emotional mirroring, what some scholars term “resonance.” I’ve seen it in my own life and the life of my children. When our psyches exist under certain forms of stress, we want the world to look the way we see it rather than to be deeply understood or to exist in profoundly loving relation. We want people to suffer as we suffer. Misery craves company. So people of a particular cast of mind want reassurance that the tragedy, the trauma, is real and irredeemable. I’ve had moments myself that feel just that way, plenty of them. And I’ve heard those words hundreds of times from people I know and love. It’s hard not to remember an emotion expressed so powerfully.

Still, as I’ve been watching closely, I think that’s usually depression talking. I’ve learned that much from all the therapy sessions with my daughter, who sought (unsuccessfully, thanks be to God) to end her life as a pained exit from the anticipated grief of her mother’s advancing cancer. I know how real and strong and important emotional mirroring can feel—can be—for some of us. I’ve felt it myself. There are days when I just want bleak resonance with the extremity of my sadness; those are rough days indeed. But that’s not most days, not even most sad days.

Having partaken of both emotional states at great length, I can see the difference between grief and mental illness. Grief is normal and strong and even a bit beautiful in its pain. It’s not just tragic. Grief is a form of love and a connection to meaningful vastness. Grief is a source of solidarity and affection and tenderness. It is a turning outward as much as inward. It can also, of course, be annihilating. Particularly when it intermingles with or even transforms into depression, anxiety, psychosis, or the other plagues flowing from Pandora’s box. Mental illness wears many faces, but it includes despair, self-hatred, and rootless pain. It is not a form of love, but a force that threatens love. It is hopeless.

All these years into intimate familiarity with grief, I’m not persuaded that treating us all as if we were mentally ill does anyone much good. Pushing ourselves to believe that tragedy is pure trauma does violence to the world in all its splendor. What I’m proposing is rather harder than the two extremes we hear the most about: reciting Hallmark cards with our fingers in our ears or hopelessly (if companionably) resonating to despair. What I’m proposing is that we share grief.

I remember when Kate’s cancer recurred six years ago. We were watching general conference a couple months later, and the stories about cancer were about people dying despite fervent prayers for rescue. We felt a bit exasperated, as we had hoped that the sermons would be uplifting and hopeful. After laughing uncomfortably, we debated whether to be angry. We realized that there were people listening who were already on the other side of a cancer tragedy, but we knew that there were people who’d had their prayers answered in sad and terrible ways and they needed to get some companionship. We as a family would have been better served by happy stories about freedom from a death sentence. But we didn’t get that. We digested this fact together: our needs were not met while others’ were. We realized that we must share the Church, share the words and stories. In love, we belong to a body that sometimes will not work for us because it is serving others with distinct needs. In the midst of our bereavement, we will have to make accommodations. We will need to share grief.

This sharing of grief has another face, one that for me, has been among the hardest and holiest work of my life. As a cancer husband and then a widowing single father, I realize that I am often asked—whether I want it or not—to be the vessel of a community’s worry and dread. With the best of intentions, no small number of relative strangers have rushed up to me to express the depth of our tragedy when all I wanted was a world where Kate was still physically present. The pain of such awkward encounters has often been acute, and initially, I tended to flee in anger and pain. I can’t remember when I finally figured out that I had another option. Instead of running away, I could admit that I was called sometimes to hold grief for others. It was hard work, and work I didn’t want to do. But, as I started this new work, I came to see that it was holy. The effort to share grief pulled me out of myself. It did not make my grief any easier; it was not a treatment. But it was sacred practice, and in the pursuit of the sacred stands the sublimely troubling dream of heaven-on-earth. And that is a dream worth fighting for.

I would never hold another bereaved person to this standard. If I shirk this duty, I am not a bad man. It is fair for me to ask others to share my grief by giving me space and tolerating my bad manners when they overstep bounds. But there will be times, many of them, when I have the strength. And when I have that strength and I exercise it on behalf of others, I feel an extra measure of power and grace. Among the many strangely beautiful gifts of this bereavement has been the calling and capacity to give from my deep woundedness. That grace is the painful promise of a shared grief.

Sometimes shared grief can feel too much to bear; there are limits to the burdens weary shoulders can carry. Kate told me as we started to watch the different chemotherapy treatments fail, one after another, that she’d rather have people say hopeful or kind things to her than to tell her how tragic her life was. Things were not going the way she wanted medically, to be sure, but she did not think of her life as a tragedy. One well-intended friend told Kate that this phase of her life was excruciating. Kate bristled. She was busy trying to live as well as she could with the time she had left. There was richness and beauty and poignancy. She had little desire to luxuriate in the trauma of cancer. The constant din of excruciating tragedy was not true as Kate saw it. Her life was hard, and it was glorious.

I’ve found this true for myself as I’ve walked this grief, even admitting that I’m a more melancholy and pessimistic soul than Kate ever was. Occasionally, I want someone to resonate with the grief, to speak the tragedy, but mostly I want buddies in the mountains, gentle company for dinner, visitors who have something good or useful or interesting to say. Sometimes even someone who needs the gravity of my grief to soothe their souls. I don’t want pontifications or expatiations. More than anything, I am grateful for help with parenting and an expression of affection for Kate or me or the girls. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach here; there is the sharing of our hearts.

And I think that’s where shared grief points us: watching and wondering, call and response, testing the waters. And above all the awareness that we are all bound together in our shared frailty, our common tenderness. We are bound in the promise that every life will end and every mortal hope will fade into the dust. And we are bound in the covenant that, in all our grief and grievousness, we are glorious and holy, the people of heaven.

Sam Brown is a physician scientist who also wonders about bigger questions. He's parenting three children at the cusp of adulthood and writes books from time to time.

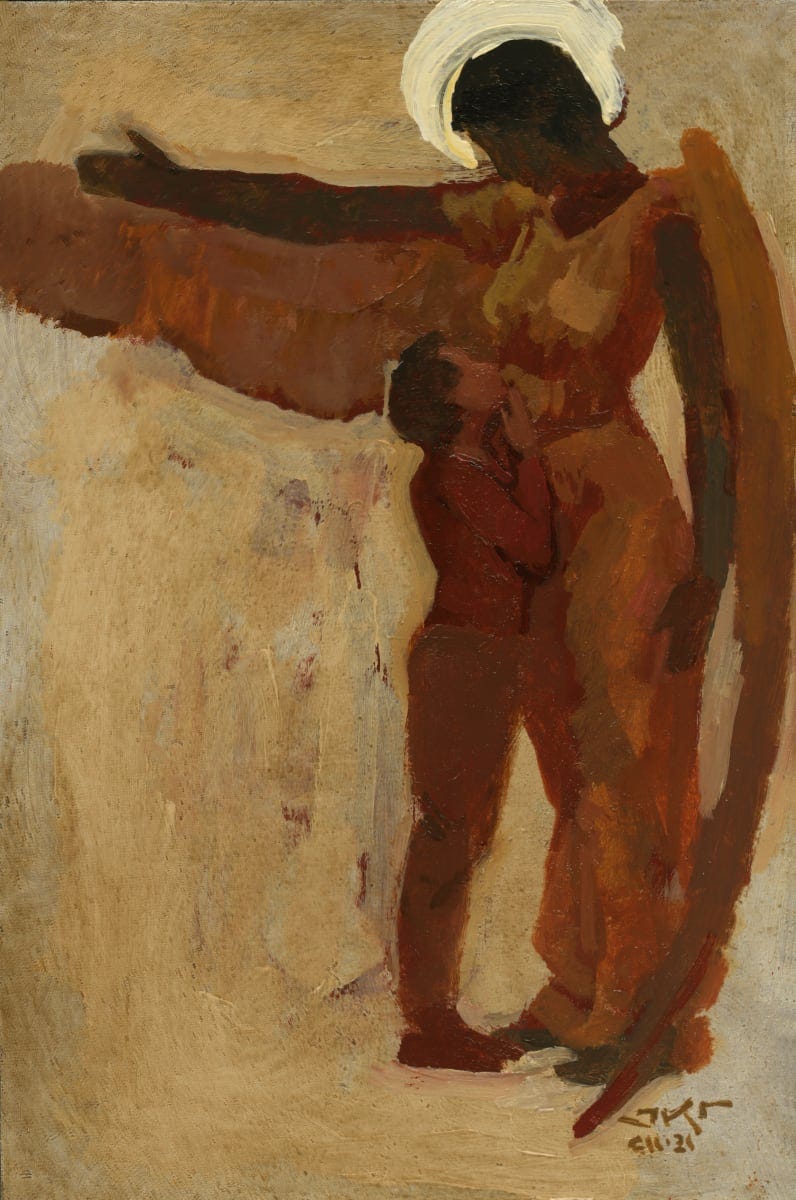

Art by J. Kirk Richards.

Thank you for sharing your journey. It’s real and helpful, and helped me feel God’s love.

I really relished reading about your journey. I am not nearly so profound, but feel I share your thoughts at the end about the things you enjoy and are helpful. I am a single mother of 10 children, most with special needs, who entered my family through adoption, some as teenagers. Because I have sons in prison and on the streets, and two kids battling alcoholism, and several with mental and physical handicaps, etc., some people look at me and I can hear them thinking, "What a crap parent she is!" Others put me on a pedestal with angels and Mother Teresa, and I am accustomed to hearing how all will be resolved in heaven, and all these experiences are teaching me things I need to know. Actually, most helpful are good crime detective recommendations, and bringing me chili rellenos. I take care of prayer, service, etc., and usually enjoy happy days. Thanks again.