Zoning for Zion

“A person can believe in God as an isolated individual, but building Zion happens only in community.” —Proclaim Peace, Patrick Mason and J. David Pulsipher

Joseph Smith never set foot in Utah, but his fingerprints are all over the map on the screen in front of me.

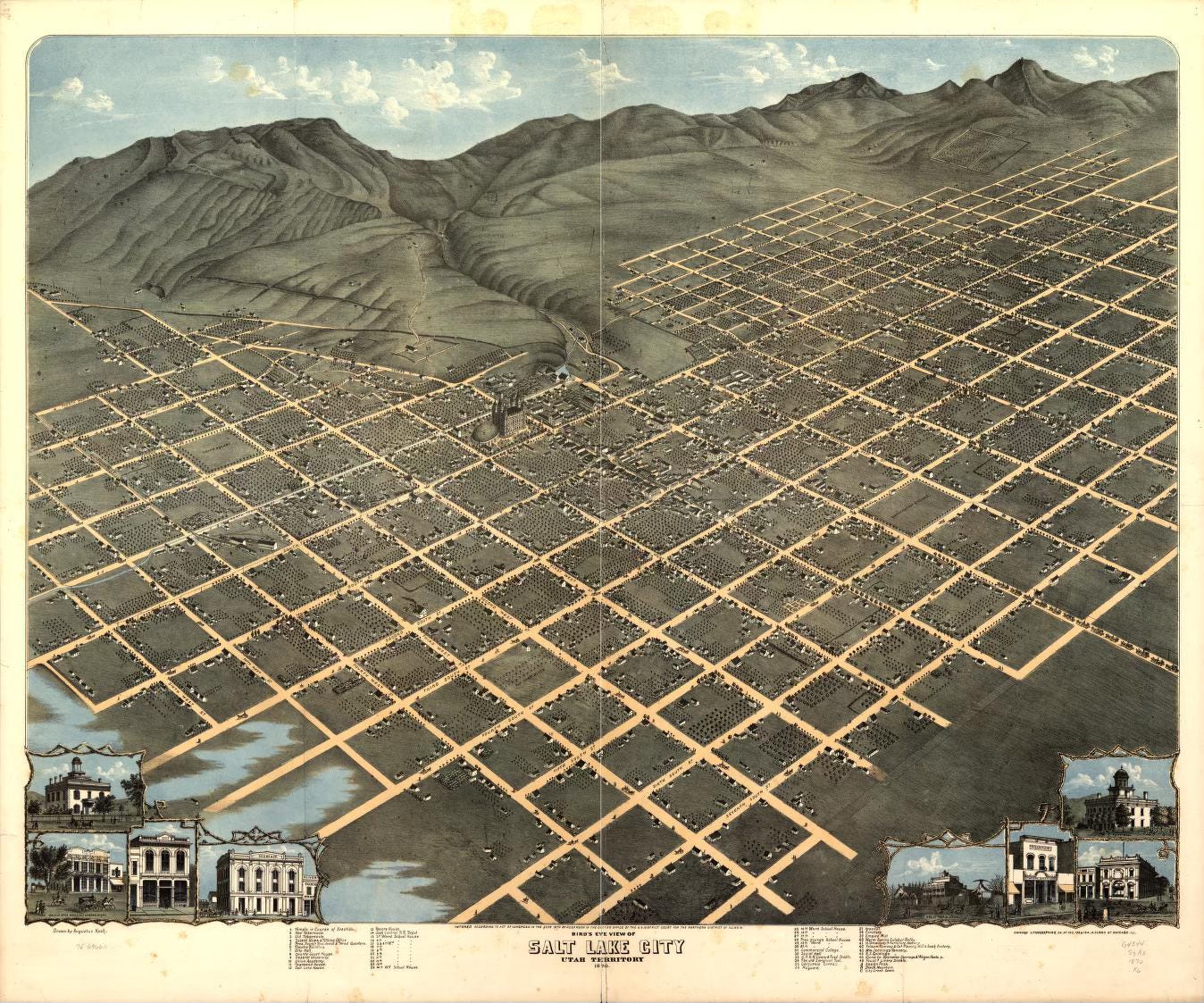

It’s a map of Salt Lake City, with neatly ordered squares moving east and west, north and south, numbers growing block by block the farther away they get from the Salt Lake Temple. I’m in the conference room of the Salt Lake City Transportation Department, and my urban design class is presenting concept plans for a Salt Lake City “Green Loop,” a vertical park encircling downtown Salt Lake City. The Green Loop aims to reclaim traffic lanes from the wide (many say “ridiculously” wide), 132-foot right-of-ways that stitch the city together, and introduce park space and greenery to downtown Salt Lake—similar to the Rose Kennedy Greenway in Boston, or Bagby Street in Houston. There’s hope that these rights-of-way could actually be a blessing to the city—a way to bring green back into the concrete jungle, improve air quality, daylight creeks, and connect the city more to the mountain it leans against. It’s the kind of hope a city planner would have.

The Plat of Zion

People link “Mormons” with “pioneers” in many contexts, but city planning isn’t often one of them. (In fact, I’ll begrudgingly acknowledge that most people probably don’t think about city planning at all.) But it should be! Because the Plat of Zion is nothing if not pioneering.

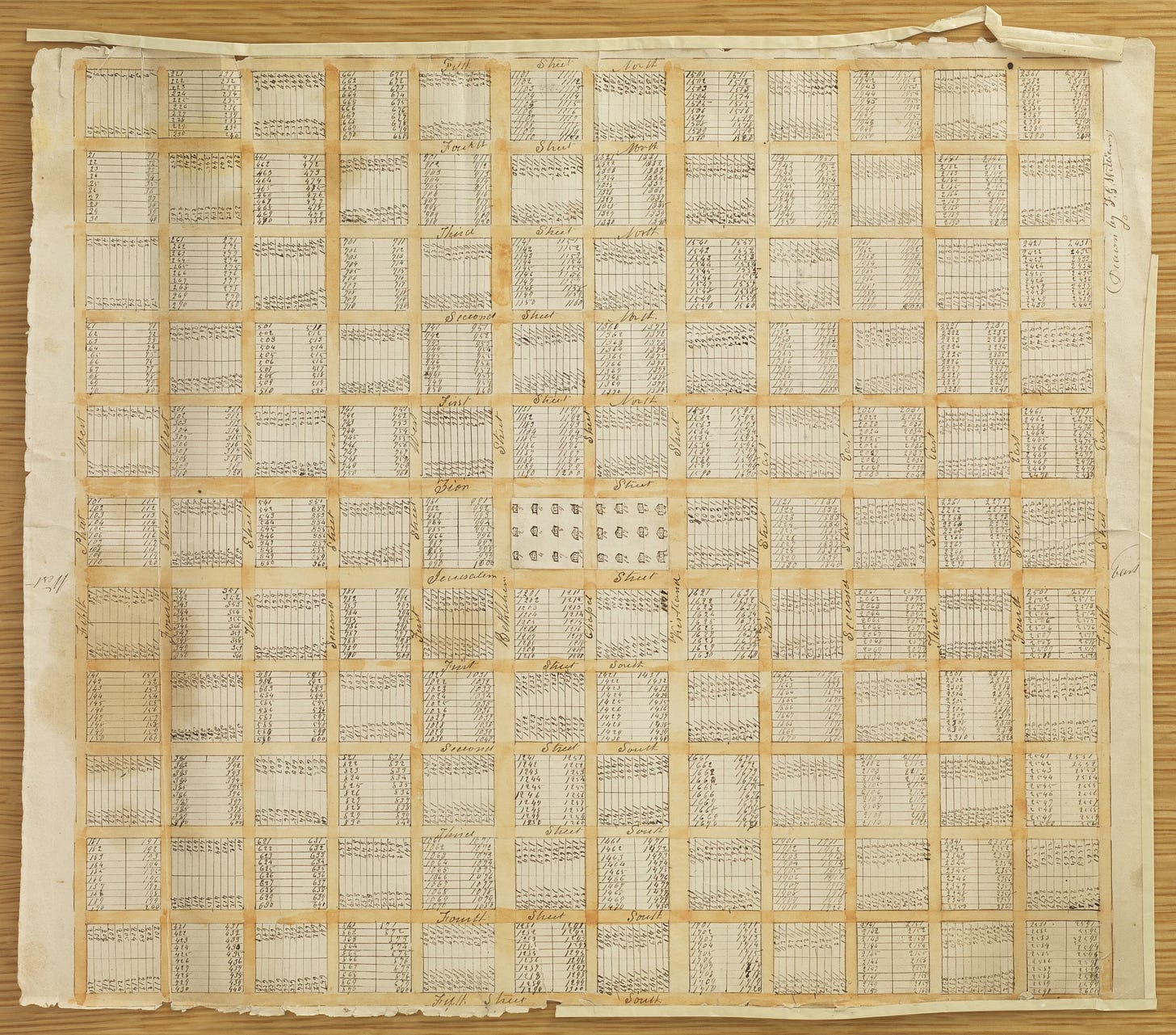

It’s a simple plan. First laid out by Joseph Smith in June 1833 and slightly altered that August, it imagined large identical square blocks divided into half-acre lots for homes, except for the blocks in the center, which would hold a whopping twenty-four temples. Next to the temples would be the bishop’s storehouse for tithes and offerings, thoughtfully placed in the center of town for easy distribution to the poor and needy. Homes would be set back twenty-five feet from the street to allow for green space, fruit trees, and gardens in front yards. Lot orientations would alter every other block from north-south to east-west, allowing for “openness and privacy,” and barns and farms would be located outside the city.

According to Craig D. Galli in an article he wrote for BYU Studies in 2005:

Joseph intended that all members of the community live within the city: “Let every man live in the city, for this is the city of Zion.” Farmers would live side by side with merchants and professionals, rather than on the outskirts of the community or on remote ranches and farms.

Like many of Joseph Smith’s ideas, the Plat of Zion is controversial. The lot orientations were intended to preserve privacy, but would also limit interactions because neighbors’ houses would not face one another. At the same time, keeping everyone in the (relatively) condensed center of town would concentrate most social life under the watchful eyes of church leadership.

I’ve thought a lot about how we “build” Zion through systems that may seem mundane, like municipal planning and zoning. The Plat of Zion is trying to answer a question, and it gives a completely different answer depending on who you ask.

Is the Plat of Zion an example of an ideal, walkable, mixed-use city with locally-owned businesses and a pedestrian-centric design? Or is it a rigid and paranoid design with awkward lot sizes and home orientations that reduce natural social interaction in order to maintain church authority? Did the plat move the early saints closer to the ideals of Zion because it helped the people live fuller, deeper, more interconnected and healthier lives, or because it ensured a stronger connection to the centralized church, focusing citizens’ lives around its authority?

How does our history shape the places we live, and the ways we live in them?

I think the biggest question the plat is trying to answer is this: What makes a place Zion?

What Is Zion?

Ten years ago, I found myself looking at a very different Zion. As a park ranger in Zion National Park, whenever a visitor would ask, “What does Zion mean?” I had a quaint and canned response—“Zion means sanctuary, of course!”

Which always made me chuckle. Because that isn’t what it means.

Zion National Park can credit its name to Isaac Behunin, one of the more far-flung pioneers sent south for the Church’s “cotton mission” in the mid-1800s. I was always fascinated by Isaac while I worked in the park. He arrived in Zion Canyon in 1863 and is quoted in one journal as having said, “A man can worship God among these great cathedrals as well as he can in any man-made church; this is Zion.” (This pre-dates several beloved and similar John Muir quotes by almost six years.)

The idea of Zion as found in Latter-day Saint theology (and the one to which Isaac was referring) is somewhat unusual. Scripturally, Zion is best described in Moses 7:18–19:

And the Lord called his people Zion, because they were of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there was no poor among them. And Enoch continued his preaching in righteousness unto the people of God. And it came to pass in his days, that he built a city that was called the City of Holiness, even Zion.

Building on this idea further in their book Proclaim Peace, authors Mason and Pulsipher write:

Zion is the social ideal of the Restoration. Joseph Smith declared, “The salvation of the Saints one and all depends on the building up of Zion . . . Our hopes, our expectations, our glory and our reward, all depend on our building up Zion . . . [Without Zion] our hopes perish, our expectations fail, our prospects are blasted, our salvation withers.”

Zion is the place where God's people are.

Zion is what we are all working toward.

Zion is also beautiful—or at least it should be.

Early church leaders frequently talked about how to build the best community. In one early address, Brigham Young strongly encouraged pioneers to beautify and take pride in their Zion:

Progress, and improve upon, and make beautiful everything around you . . . Build cities, adorn your habitations, make gardens, orchards, and vineyards, and render the earth so pleasant that when you look upon your labors you may do so with pleasure, and that angels may delight to come and visit your beautiful locations.

However, then and now, we may encounter difficulties with this project when the things and people around us don’t feel beautiful. As Fawn Brodie noted: “A chosen people is probably inspiring for the chosen to live among; it is not so comfortable for outsiders to live with.”

In this world, people around us often don’t align with what we feel is “good” or “right,” or what we think our community should look like. We tend to be most unhappy when the people, systems, or structures around us fall short of where we think they should be.

In 2015, I left the National Park Service and started a long professional journey toward city planning. Why? After several years of watching increasing numbers of visitors overwhelm the park I loved while the surrounding towns were subjected to enormous growth pressures, I decided I wanted to find a more effective way to help protect the things I cared about.

That’s when I stumbled across planning and zoning.

Zoning

Zoning is one of the most powerful tools a community can use to guide its future. Zoning is why your city looks the way it does—why its businesses are concentrated in one place, and residential homes in another. It’s why one building may have three stories instead of four, and why one neighborhood may have large backyards while another has none.

You can zone to increase traffic safety. Zone for density. Zone for conservation. Zone to include.

You can also zone to exclude.

Zone to keep those people out. Zone to increase property values over here, by zoning to decrease property values over there.

Zoning is a tool used to shape a community, and like any tool it can be (and has been) used for good and ill, but it isn’t the only thing that shapes a community.

Currently, I work with “gateway” communities—small towns and cities outside America’s most beautiful and iconic places. Despite their incredible surroundings, these are often communities in pain. The rise of social media has brought significant change to these rural places. No longer isolated pockets of beauty, they’ve been flagged as good investments, and homes that once used to belong to neighbors now often hold a rotating cast of Airbnb guests instead. Meanwhile, locals find it increasingly difficult to live in their hometown and workers often can’t afford to live near their jobs. The community fabric they once felt securely wrapped around them is now fraying, and they often feel frustrated and helpless. After all, what can a town of 500 people do in the face of the global tourism economy?

And on Sundays, I see another community in pain. Parents grieve children who have left the Church. Bishops struggle to address the serious personal or financial challenges in their congregations. Sunday school students shake their heads in confusion over why people don’t feel comfortable coming to church while simultaneously voicing discomfort at the way others are living their lives.

The world is full of painful change and conflict that we wish we could control, but perhaps the hardest truth to accept in this fallen world is this: We can’t stop change.

Change and conflict are certainties in life, and there are three ways a community usually responds: (1) Pretend it isn’t there, (2) Reject it—reactively put up walls to try and keep it out, or (3) Engage with it. If you acknowledge change is happening, you empower yourself to have a say in how it happens. It’s so easy for communities to pick one of the first two paths, but it’s never too late to start the third.

But how?

The Community vs. The Individual

The tension in the Church is the tension in America is the tension in city planning: How do we belong to the community, while belonging to ourselves?

Despite the ideals laid out in the Plat of Zion, in the 1930s and 40s, Salt Lake City “went from one of the most beautiful, to the most hostile cities in the west,” according to Andres Duany, co-founder of the New Urbanist movement. The post–World War II era unlocked a world filled with cheap rubber and new technologies. The rise of the personal vehicle made it so mobility no longer depended on public transportation or neighbors giving each other a ride—and thus, the Plat of Zion started to fray in Salt Lake City.

During this same period, a shift was happening within the church as well. While cheap rubber and a national desire for efficiency fueled cars and suburbia, the Cold War fueled a renewed focus on the individual, including by leaders of the church. Conference messages began to shift their emphasis to center more on individual actions rather than the community: You need to keep yourself clean from sin, keep yourself safe from temptation, keep yourself out of harm’s way.

And don’t forget—harm is everywhere.

Now, the myth of the “online community” has taken hold, ensuring that we are simultaneously the most connected and most lonely people who have ever lived—pouring fuel onto a loneliness fire that has fanned into an inferno.

The Price of “Peace”

This intense and increasing focus on our individual lives has made it harder and harder to make the case for the public good. This is also “the heroic challenge of city planning,” according to Dowell Myers, a former professor at UCLA:

The planning field is focused on community betterment, often coordinating or restricting the activities of individuals so that the public good may be enhanced . . . Given the primacy of respect for individual freedom in American culture, the concept of planning often finds it difficult to win popular support . . . Certainly every individual belongs to one or more communities, and communities comprise individuals. Nonetheless, as illustrated decades ago by game theorist Thomas Schelling, individuals acting in their own immediate interests often arrive at outcomes that are contrary to the interest of the community as a whole (and even contrary to the individual's own self-interest in the near future).

Of course, everything Myers said about planning could also be said about the church. Only, we act in ways to preserve our “peace of mind.” In 2007, Envision Utah (a major non-profit planning organization in Utah) conducted a study on community values for the state of Utah and found that:

The core Utahn value system centers around a sense of peace or peace of mind. This value dominates above all other value orientations . . . When focusing on what makes Utah a great place to live, four general pathways can be identified for Utahns—all of which include peace of mind as an ultimate value.

Peace of mind makes sense as the primary value of people who carry four to six generations of trauma. While it’s incorrect to paint early Latter-day Saints as simply innocent victims of early nineteenth-century politics, it’s also incorrect to portray them as malicious villains. As the only religious group in the history of the United States to have an extermination order issued against them, the Latter-day Saints were repeatedly and violently expelled from their homes. Early Saints were a traumatized community who moved west with a shared understanding of who was with them—and who was against them.

In church lore, it’s common to almost deify our ancestors—those ancient ones who came before us with unwavering faith and bravery, who silently and stoically bore their trials in the service of their Lord. However, I think we do them a great disservice when we strip them of their humanity and their struggles; how much they hurt, and wrestled, and doubted. Isn’t that worthwhile, too?

It’s the online “community” that demands everything be polished; it shouldn’t be the real one.

One of my ancestors sent a scathing letter back to the Isle of Man after joining the saints in America, warning their family not to follow:

We have seen many things which we cannot judge to be right, and from which we have cause to fear that all is not right among the Mormonites . . . We wish for all your company, but we do not wish to see you in trouble. This country is not so good as the accounts give of it. You may blame us for removing, but we were seeking for truth, and wished to obey it. We would be glad to see you again, if the Lord permits; so we close this letter by letting you know that we enjoy a measure of good health.

P.S. — The so-called, hard hearted crew and officers of the ship showed us more kindness and respect on our passage, than those Mormonites did to what they call their brethren and sisters. However, we should not blame the whole sect for the conduct of their leaders. My advice to Cowley is to try to recover back his own place again, for so much unrighteousness and fraud as we have seen, which has caused us to wander so much to and fro. Let him be in no hurry in coming here, but weigh the matter well. The Mormonites may speak a deal of truth but their conduct and works are contrary thereto.

From the letter, you’d expect them to be on the brink of apostasy. However, one of these ancestors went on to help settle one of Utah’s more remote communities, and become a bishop within it. For better or worse, they stuck with the community long enough to find the good amid the imperfect. They were able to find their place, and find a measure of peace where it was not immediately apparent.

As a community, many in Utah have been willing to sacrifice a lot at the altar of “peace of mind,” but sometimes that altar was built to false gods. In a zealous attempt to follow rules and convince ourselves we’ve checked the right boxes for eternal happiness, we end up too anxious to be happy now, and shun those who we feel would put us at “risk” of temptation. To keep ourselves safe, we cut off opportunities for growth by limiting both our exposure to negativity and our exposure to beauty and truth. Worse, we shut out individuals—neighbors, friends, sometimes even our own children—who choose different paths than those we’ve deemed as “right,” and create holes in our lives that didn’t need to be there.

The tragedy is connected to this question: How often were those sacrifices made in the name of building Zion?

Zoning for Zion

I don’t know how much Brother Isaac Behunin saw of Salt Lake’s Plat of Zion before he set off toward the canyon. The little town of Zion he christened no longer remains (the homesteads of the eight or nine families who lived there have been replaced by the Zion Lodge and other park facilities). However, just down the road is Virgin, Utah, another pioneer community. In Virgin, you’ll see a main street, 100 W, and 100 S laid out in their dutiful square—the Plat of Zion, copy and pasted across the state wherever the Saints spread out.

But you’ll also see Mill Street and North Street. It seems the farther away from Salt Lake communities got, the more liberties were taken with the Plat of Zion. People made a place their own in ways that helped their community survive, and even thrive. A city is a place, but a community is a group of people who come together in common purpose.

A city is never done being “planned” for. Community plans and zoning maps are often updated every five to ten years in order to help the community respond to the ways it grew or shrunk, how its economy changed, and so forth.

And just like a city, Zion is never done being built.

“As a work in progress, Zion is as much process as product,” say Mason and Pulsipher. They quote Joseph Smith:

It will not be by sword or gun that this Kingdom will roll on, but by the power of truth. Zion cannot be established with violence or coercion, only by persuasion, by long-suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned.

Zion may be where God’s people live on Earth, but it doesn’t mean we’re perfect. It just means we’re trying our best to build a better community, with love for each other and ourselves along the way—a challenging concept for us in our culture renowned for its struggle with perfectionism.

But that’s OK: like the Restoration itself, Zion is a work in progress. Can we make space for the imperfect in our Zion? Can we make space for the people with questions, and problems, and inconvenient pasts? For the people who keep falling short, or those who don't seem to be trying?

Yes! There is still time and space to continue and to do better. Let’s get to it.

Elizabeth grew up in a small town, and has a passion for helping communities navigate change. When she isn't working, you can find her and her husband climbing a rock, living out of a tent, or driving down a dirt road covered in dog hair.

Art from the Library of Congress, The Joseph Smith Papers, and The Church History Catalog.

Love this. I did my senior capstone on city planning, and even a semester of study helped me understand much better how important and impactful it can be. It's an avenue of work that's a great example of choosing to act and not to be acted upon, to guide a community's future toward a better place, and that requires vision and humility.