In June 2025, Wayfare editor Rachael Johnson and Mark Wrathall co-hosted an interdisciplinary conference at Oxford University on materiality, embodiment and religion. Caroline Walker Bynum, a renowned historian of medieval material and religious culture, delivered one of the keynote addresses— a gorgeous, insightful and provocative comparison of the writings of the medieval mystic Julian of Norwich and contemporary American ecological writer Annie Dillard, relating to questions of suffering, love, redemption, and creation. The Anglican Theological Review recently published her remarks and has generously granted Wayfare readers access to the full-length text for a limited time.

[...I begin my talk today by considering] how concepts of and assumptions about not only objects of devotion but materiality more generally underlie and permeate the writings of two of my favorite mystics: Julian of Norwich, an anchoress associated with the church of St. Julian in Norwich, England, who lived circa 1342–1416, and the prolific twentieth-century writer, Annie Dillard, whose Pilgrim at Tinker Creek won the Pulitzer Prize in 1975. These two case studies raise larger questions about how assumptions about the world (which I include under “materiality”) and religious experience (which includes mysticism, spirituality, and religious life) intersect.

I will not be arguing that Julian and Dillard have similar responses to the world or are embedded in it in similar ways. In fact, as we shall see, Dillard explicitly rejects Julian’s response to the complexity of physical experience. Rather, I am going to ask similar questions about the context of their nature-imbued mystical experiences: how is their understanding of the world in all its complexity related to ideas about nature and matter contemporary with their visions; what understandings of art—devotional and secular—inform their mysticism; does it enrich our understanding of mystical experience when we notice that each wrote in a period in which religious and ethical writing by women flowered? Indeed, I shall suggest that the fact that they differ so radically in both the materiality with which they engage and the ways in which they respond to it helps us understand the complex and multiple ways in which a religious self can be embedded in the material world.

Before I begin, a word about the texts I am discussing.

First: Julian. There are two versions of her Revelations or Showings, written in Middle English, which recount her series of visions that began with one of the dying then glorious Christ and of demons received on May 13, 1373, when she was thought to be dying herself. The short version of these was written down in 1378; the long version was supposedly written about 1395, after, she says, she had come to understand elements of the visions she did not at first understand.

Second: Annie Dillard, a prolific author of memoirs, two novels, and the lengthy, early work Pilgrim at Tinker Creek that won the Pulitzer Prize. I concentrate on Tinker Creek, which muses on her year of living alone very close to nature in the Roanoke Valley of Virginia, her dense and theological Holy the Firm of 1977, and her 1989 The Writing Life.

The materiality of these texts—not just their use of bodily images but also the central place of imagery taken from the physical world—raises several questions. Both Julian and Dillard have elements of affirmative theology, seeing the world and our experiencing of it as a spilling out from God, but both are clearly fundamentally in the long, negative approach in western Christian thought that ascends toward the Other by the stripping away of particulars. Moreover, in both mystics, it is impossible to clearly distinguish what ethicists call moral and non-moral evil—that is, wrong, harm, pain, unfairness, sin, willed by the human will, in contrast to the pain, suffering, and horrors of all living, physical existence in the world. Indeed, to both, what philosophers call “the problem of evil” is the problem of the universe itself, not just that we do wrong but that there is cruelty and wrong in nature, although Dillard dwells more on the cruelty of nature than Julian and Julian agonizes more over willed human evil (that is, sin) than Dillard. Nevertheless, these two mystics, so distant from each other in time, both write in a prose saturated with an acute sense of and interest in what not just the body or the self but what the world is like. Why engage so thoroughly with the world?

Read the full article here.

Caroline Walker Bynum is a University Professor emerita at Columbia University and Professor of European Medieval History emerita at the Institute for Advanced Study. She has authored nine books, including Jesus as Mother (1982), Holy Feast and Holy Fast (1987), The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200-1336 (1995, second edition, 2017), Metamorphosis and Identity (2001), Christian Materiality (2011), and Dissimilar Similitudes: Devotional Objects in Late Medieval Europe (2020). Additionally, she has published several autobiographical essays, such as “Growing Up in the Shadow of Confederate Monuments,” in Common Knowledge 27:2 (2021) and “Who Does She Think She Is?” in Medieval Feminist Forum 57.2 (2022).

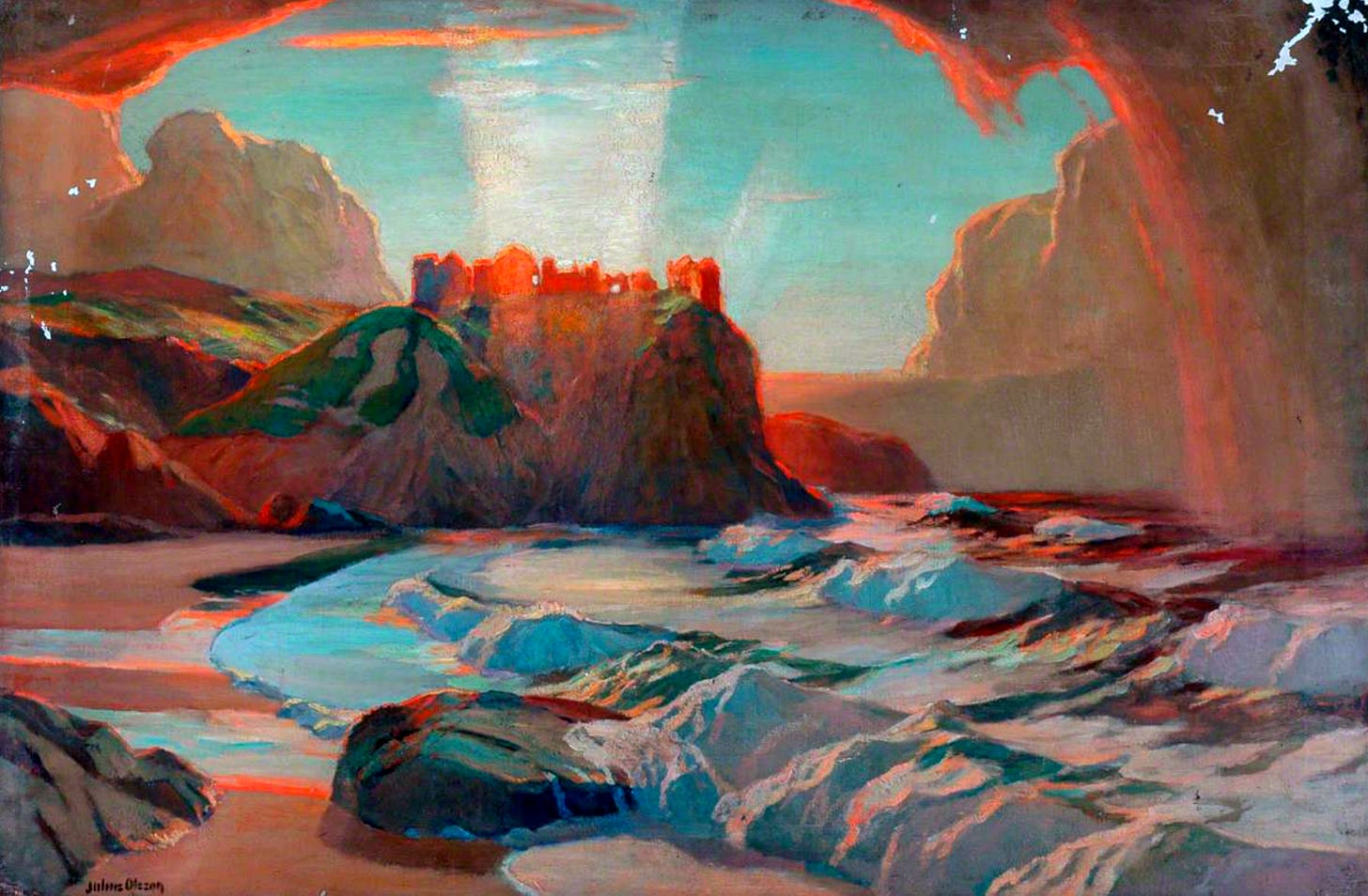

Art by Albert Julius Olsson.