What the Natural Man Doesn't Know

The Spirit's Way of Knowing

The natural man is a major influence on how LDS believers understand their human nature. By itself the idea is vague, but King Benjamin says that the natural man is an “enemy to God”—so whatever it is, it must be bad. The vagueness, together with this negative association, invites us to clarify the idea by filling it with all the desires and compulsions that lead us to nasty behavior. The result is all of human immorality and vice, wrapped up in a single notion. And then, since King Benjamin urges us to “put off” the natural man, we focus on ridding our lives of all that badness, even when doing so requires that we excise parts of ourselves that are integral to who we are—and that we can never truly “put off.”

We’re left to lead bifurcated lives: some human parts of us seem good, but others seem forever separate from and even inimical to spirituality. This view on the natural man puts fundamental aspects of our experience not just in opposition to God, but at war with him.

This is not, however, the only way to understand the natural man. With a careful look at 1 Corinthians 2 (and other passages of scripture), we can reach an alternative view that allows us to see ourselves more truthfully, and perhaps, compassionately, while also demanding deeper discipleship.

King Benjamin isn’t the only prophetic witness to speak of the natural man. Let’s begin by taking a biblical view, to see how other sources might understand it and its connections to the Holy Ghost.

In the King James Bible, 1 Corinthians 2:14 is the only place the term “natural man” appears.

But the natural man receiveth not the things of the Spirit of God: for they are foolishness unto him: neither can he know them, because they are spiritually discerned.

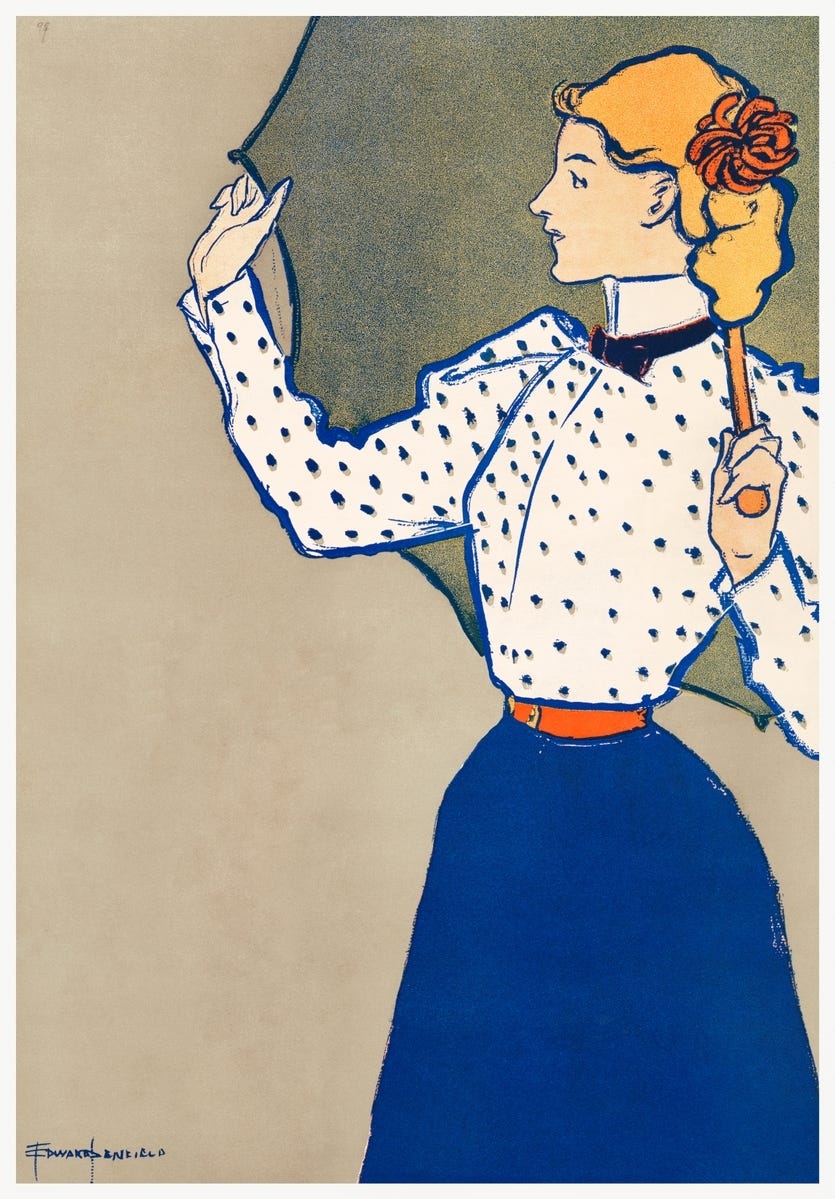

There are important things happening in the verse’s original text that we may not notice in English. Let’s look at a few of the English words with their Greek counterparts and their definitions:

With these words before us, let’s take a look at them in the context of 1 Corinthians 2.

In verse 14, the Greek words translated as “natural man” are psychikos anthrо̄pos. According to our definitions above, the psychikos anthrо̄pos, or natural man, is a person whose life centers around the naturally-occurring psyche, unmodified by divine influence. The psychikos anthrо̄pos has limitations, however. He cannot receive things of the Spirit of God, pneuma, because he cannot discern them spiritually, pneumatikо̄s.

Verse 15 introduces us to the spiritual man: “But he that is spiritual judgeth all things.” This man is pneumatikos. In Greek, a long vowel marks the difference between the adverb pneumatikо̄s and the adjective pneumatikos. The pneumatikos, or “spiritual person,” is the one who lives pneumatikо̄s, “spiritually.” In this verse, Paul says that, unlike the natural man, the spiritual person is able to “judge all things.” The Greek word translated as “judge” is the same word for “discerned” at the end of verse 14.

That’s a lot of unfamiliar terms, I know. But it’s in the contrasts between them that we find a new understanding of the natural man, especially when we focus on the concepts of knowledge and our experience with God. Using the original Greek, our new understanding of the natural man centers on our ability to abide the Spirit’s presence and receive revelation. It does not center on vices like anger and greed.

Taken together, verses 14–15 distinguish between two kinds of people: the psychikos or natural person, and the pneumatikos or spiritual person. For Paul, these two people are opposites and so cannot be interpreted independently of each other. To understand the natural man, which is the side of the duality defined by absence, we must first understand the opposing side. The pneumatikos person is our protagonist and the psychikos is our foil.

The pneumatikos person, then, is someone with the presence of the spirit; they are under the Spirit’s influence. They have received God’s Spirit to accompany them and try to live by every word that proceeds forth from the mouth of God. Their life is full of light and revelation. By the gift of the Spirit, the pneumatikos person can thus “discern” or “judge” things, since Paul is speaking here of the Spirit as a means to knowledge.

So if the pneumatikos person is one who has the Spirit, then what is the psychikos person? Since Paul means to contrast the two, the psychikos person is that which the pneumatikos person is not. In other words, the psychikos person is simply someone who doesn’t have the Spirit.

And that’s it. The “natural” part of “natural man” refers only to someone who has not received the gift of the Spirit, or who doesn’t currently enjoy its presence in their life. That’s all the meaning psychikos carries here. We don’t need to fill the idea of the natural man with any immorality or badness, because there is none to include. The psychikos person is just a human without the Spirit, and the term, in the Greek, carries no value judgment in itself.

Notice how this view of the natural man differs from our traditional one. This biblical view explains the idea in terms of knowledge and our ability to receive knowledge from the Spirit, and not in terms of the assumed evil of human nature. Yes, the psychikos person doesn’t have the Spirit—but designating someone as such doesn’t judge their righteousness or involve any specific moral claims. The designation merely describes them as someone who doesn’t currently have the Spirit, and suggests nothing about why they don’t have it nor any judgment about the fact that they don’t. There could be many explanations for why they don’t have it, of course, but by itself the notion of being psychikos, natural, indicates none of them. The notion has no connection, for example, to anger, selfishness, or sexual desire, nor to any of the other things we like to include in the way we usually explain the natural man.

Since we build so much badness into the traditional natural man, applying the term to someone usually suggests a harsh judgment about their righteousness. And because we tend to enrich the notion with specific immoral acts, the term also includes assumptions about the behaviors that make someone a “natural man.” In effect, we take an idea that in itself makes no moral judgment—one commentary says that psychikos involves only “value-neutral nuances of an ordinary person or person who lives on an entirely human level”—and we fill it with all the moral judgment we can muster. Indeed, in contrast to the view I’m suggesting here, the traditional LDS one is not value-neutral at all. In our interpretation of King Benjamin’s remark, we usually attach negative value to many parts of our human nature, some of which we have little control over.

Speaking of the pneumatikos or spiritual person, another commentator writes, “‘The one who is spiritual’ is such because indwelt, renewed, enlightened, directed by the Holy Spirit. Such persons, believers, are transformed by the Spirit so that they are enabled to do what psychikos anthrōpos cannot.” And what the psychikos anthrōpos cannot do, in their current state, is know and discern spiritually. It is for this reason that the natural man is an enemy to God, and not because human nature is bad. We’ll return to this point below.

This argument transforms a troublesome idea. We can cut to the heart of the matter by asking: do you believe? Have you received the gift of the Holy Ghost? Do you strive to keep its company? Then you are not the psychikos person—and so you are not the natural man. You are not an enemy to God, and therefore no part of your human nature makes you so.

The larger context in which Paul discusses the psychikos person helps illuminate the kind of knowledge the Spirit is able to offer. Paul’s words before 2:14 focus on knowledge and wisdom—he mentions the “wisdom of God” (1:21), which is the “cross” (1:18) and “Christ the power of God, and the wisdom of God” (1:24). By “demonstration of the Spirit and of power” (2:4) he was able to preach this wisdom, because normally it’s “in a mystery” and could even be called the “hidden wisdom” (2:7); therefore, the psychikos person would not be able to receive it. The wisdom of God is Christ and the atonement, and we come to know these things as pneumatikos people, by the power of the Holy Ghost.

Paul further teaches that no regular human can access the mystery: “none of the princes of this world knew” (2:8), and no “natural” or Spirit-less manner of knowing can reach this knowledge. It is something that “eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man” (2:9). Only by the Spirit can we know it, for “the things of God knoweth no man, but the Spirit of God” (2:11) and “God hath revealed them unto us by his Spirit” (2:10). When we receive the Spirit and become the pneumatikos person, we become able to do what the psychikos anthrōpos cannot: “know the things that are freely given to us of God” (2:12).

These early remarks build toward the great distinction Paul draws between the psychikos person and the pneumatikos person. The context emphasizes wisdom, knowledge, and ways of knowing, and those are his emphases in distinguishing the two figures. He’s arguing that we can receive a special kind of wisdom or knowledge only when we have the Spirit. If we don’t, it’s not just unlikely we’ll receive it, it’s impossible: “the psychikos person receiveth not the things of the Spirit of God: for they are foolishness unto him” (2:14). The psychikos person, Paul’s natural man, simply cannot receive the crucial revelation.

In accordance with Paul’s earlier words, we might see this crucial revelation as the knowledge that salvation comes only through Jesus Christ. Perhaps Paul once thought that his fervor for the law was sufficient for deliverance: do these things, and God redeems you in exchange. But he learned, as we all must, that sinners receive grace, even the same grace that changes our nature—not because our nature is evil, but because it simply isn’t yet complete.

In sum, the biblical witness to the term “natural man” refers to that person’s ways of knowing. There may be many reasons why someone is psychikos, but Paul attends to none of them in his exposition, because they aren’t relevant. All that matters is that such a person cannot receive knowledge from the Spirit and so shuts themselves off from revelation until, at some moment, they are spiritually reborn—and no longer psychikos.

Restoration scripture on the natural man

These lessons from Paul help us modify our understanding of the natural man as found in restoration scripture, but not just in King Benjamin’s address in Mosiah 3:19. The term also appears in Alma 26:21, Doctrine and Covenants 67:12, and Moses 1:14. In these passages we find support for this new view, and perhaps the motivation to reject the old one entirely.

After naming the wonderful things the Lord has done, Ammon asks in Alma 26:21, “What natural man is there that knoweth these things?” Then he answers: “There is none that knoweth these things save it be the penitent.” Here the natural man also appears in the context of knowledge and knowing, and Ammon affirms a difference in the ways of knowing for two different individuals: the “natural man,” interpreted as the psychikos person, and the “penitent,” or the rough equivalent of the pneumatikos person. The latter can receive the crucial knowledge: “unto such it is given to know the mysteries of God. Yea, unto such it shall be given to reveal things which never have been revealed.”

The discussion surrounding the natural man in Doctrine and Covenants 67:12 once again centers on knowledge and experience of God. Verse 11 reads, “For no man has seen God at any time in the flesh, except quickened by the Spirit of God”; that is, only the pneumatikos person, endowed with the Spirit, can see God. Verse 12 then follows: “Neither can any natural man abide the presence of God, neither after the carnal mind.” No psychikos person is able to bear this endowment, and so they cannot receive the experience nor the corresponding knowledge.

The natural man in Moses 1:14 also concerns knowledge and knowing: “For behold, I could not look upon God, except his glory should come upon me, and I were transfigured before him. But I can look upon thee in the natural man.” If we are psychikos, utterly without the Spirit, there are some things we’ll never see. They may be foolishness to us, so that we never notice them, or it may just be impossible for us to perceive them at all.

We saw the biblical origin of the concept of the natural man in a passage about knowledge, and the three restoration occurrences of the same concept outside of Mosiah 3:19 all center on knowledge as well. On this basis, I suggest we abandon the traditional way of understanding the natural man in favor of this new interpretation: one focused on the Spirit, revelation, knowledge, and the value-neutral opposition between the pneumatikos and psychikos persons. It isn’t that psychikos people are bad; it’s that pneumatikos people know more, and so can live and act with greater righteousness.

Indeed, we ought to understand the natural man as an epistemological designation, or an epistemological category. “Epistemological” means “having to do with knowledge,” so to call the term an epistemological designation is to say that the term concerns knowledge and ways of knowing. We usually assume the natural man is a moral or behavioral designation, centered on various evils of our nature. But this is not correct. To be a natural man is to be a psychikos person, someone who lacks God’s gift of the Spirit, and is therefore unable to know certain things about Jesus Christ and the atonement until they undergo a change in their way of knowing.

With this understanding, we can return to Mosiah 3:19. Why is the natural man an “enemy” to God? That doesn’t sound like a value-neutral thing to be. But the reason the natural man is an enemy to God is merely that he lacks the Spirit and thus cannot receive things God otherwise wishes to teach him. Hence he cannot be changed. It’s not that God is his enemy; it’s that he casts himself as an enemy to God, a person inimical to God’s designs of progress for his children. And he remains an enemy in that way unless “he yieldeth to the enticings of the Holy Spirit and putteth off the natural man and becometh a saint through the atonement of Christ the Lord”—that is, he remains psychikos unless he allows the Spirit into his life so that he can learn and be born again pneumatikos, through Christ.

In this process, the formerly natural man becomes “as a child.” One thing children do better than adults is learn: they learn quickly and widely, and they retain and act on what they know. The childlike qualities King Benjamin names, like meekness, humility, and patience, help us recognize what we don’t know so that we can “put off” the ignorance of the natural man.

Substituting our alternate translation of psychikos anthrōpos for the phrase “natural man” in Mosiah 3:19 underscores the point:

For the spiritless person is an enemy to God and has been from the fall of Adam and will be forever and ever but if he yieldeth to the enticings of the Holy Spirit and putteth off the spiritless person and becometh a saint through the atonement of Christ the Lord…

Notice that the psychikos or spiritless person has only been an enemy to God “from the fall of Adam.” Why from then on? Because that’s the moment when they were separated from God’s presence, and when the Spirit became the medium by which they would experience that presence in this life. The psychikos person cannot receive anything through that medium and so cannot partake of God’s presence. But as soon as they receive the Spirit into their life, they are no longer psychikos, no longer spiritless, and no longer an enemy to God.

In Mosiah 3:19, King Benjamin speaks not of the natural man’s righteousness, or lack thereof. He’s instead speaking of him as someone who cannot receive the Spirit, cannot gain new knowledge or be transformed, and therefore cannot progress. It is in this respect that one of God’s beloved children could be an “enemy” to him. God does not hate us or wish to abandon us, but when we reject learning and change and growth, we set ourselves in opposition to God’s progressive nature. The insight that God progresses is a fruit of restoration revelation; interpreting the natural man in light of that insight is truer to restoration principles than any idea we may come up with about the fundamental depravity of human nature.

In fact, when we see the natural man in this new way, we realize that our very tendency to view our nature falsely, as innately bad, is itself part of the natural man! The traditional understanding of King Benjamin’s remark, with all its moral and behavioral associations, is exactly the sort of ignorance we must put off. Into that idea we inserted all the parts of ourselves we assume are bad. But that idea misunderstands which parts are bad, and why.

Knowledge and the new birth

Spiritual rebirth transforms our character and desires. But this rebirth is also a transformation of knowing, as we go from the psychikos to the pneumatikos person and therefore acquire new ways of receiving the Spirit. New vistas of knowledge unfold to those born of God, for the Spirit acts on them and on their bodies such that they become able to know things they could not have otherwise known.

When we are selfish or constantly seek to gratify our desires, we act as though we’re ignorant of the knowledge we’ve received from the Spirit. But those who have been once illuminated can only feign ignorance, and our pretense of not knowing makes us again, if only temporarily, the natural man. In response, the Spirit will invite us, entice us, and strive with us so that we may become pneumatikos again. When we embrace learning and change—when we let the Spirit soften our callous hearts—we embrace the atonement’s power to build us anew. By choosing to accept the knowledge God has given us and letting it govern our lives, we put off the natural psychikos person once more.

In our flawed definition of the natural man, we attempt to put off parts of ourselves that we cannot separate. As a result, our view of ourselves becomes hopelessly antagonistic—we’re at war not only against God, but also against ourselves. But it doesn’t have to be this way. I’ve tried to point to a new view by showing that this war is happening only in our minds, and that the conflict ends as soon as we allow it: by seeing ourselves differently.

From this vantage, we understand the great responsibility that knowledge brings; we understand why the Lord teaches us that “unto whom much is given much is required” (D&C 82:3; see also Luke 12:48). Unless the light God gives us makes a difference to our actions and character, then we might as well not have received it, whether we’re pneumatikos or not. For unlike the knowledge we gain by worldly means, what we get by revelation isn’t just information about the world. It also becomes the standard by which we live. The power is in us, and we’re agents unto ourselves (D&C 58:27–28). What is that power? The knowledge we can’t gain any other way.

Bryce Gessell writes Climbing the Rainbows, a weekly Substack on the foundations of LDS thought. He teaches philosophy and history of science at Southern Virginia University. He earned a PhD at Duke in philosophy and neuroscience. See more at bryceswrite.wordpress.com.

Art by Edward Penfield