What the Ainu Know

Theirs is the keeping of life.

The thing is, no one really knows where they came from. Maybe that’s why I’m fascinated with them, my father tells me. If you ask anyone on the streets of Japan, they pause and then say shiranai, ne, surprised by the fact that they can’t tell you. Surprised to realize they don’t know.

As if their slender black boats just rose up out of the water one day of their own accord, draining as they spiraled up from the play of obsidian waves, masts reaching into the gentle, murky mists. Or emerged from the long moan of the earth, breaking that rich, black loam like také sprouts in the woody biomass, shapes shifting out of shapes, earth stepping out of earth with flesh and legs and eyes and chests, each with a crown of nature. Owning those frigid, tenacious tundras up north, those islands that cover with snow.

But most likely, they just were—that’s what their legends tell you.

One hundred thousand years before the children of the sun, the Ainu lived here. The bear people.

My father told me about the Ainu, and his curiosity sank into me like rivers, spreading wide and flowing through. Japan’s indigenous people that I could only know by story, by pictures, by government reports.

They eat bear, says my grandmother, with raised eyebrows. Kuma taberu yo!

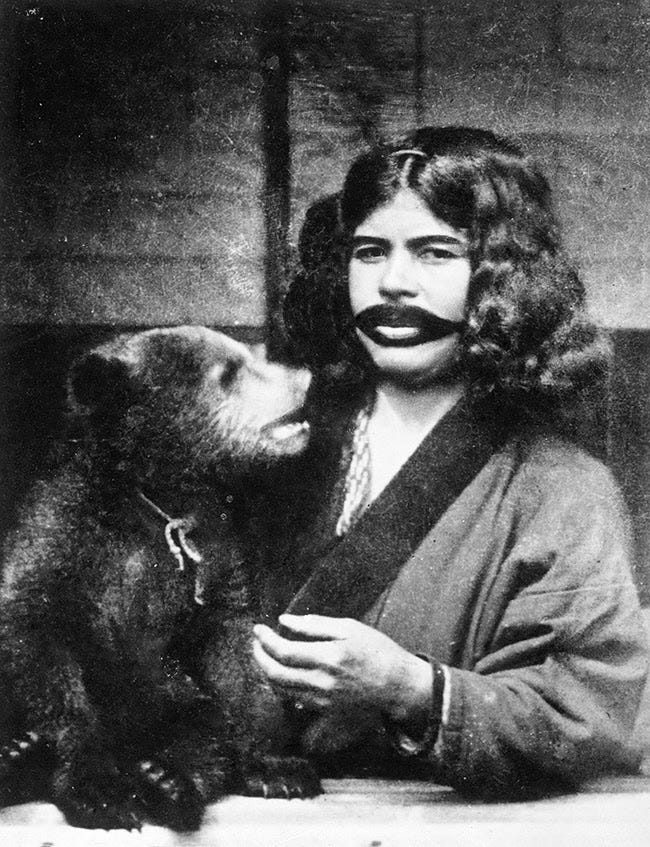

The woman in the photograph I’ve pulled up on my laptop speaks softly. We know what the bears say, she whispers. Bear whisperers. Inky mouthed whistlers. Salmon fishers. They shake the rivers with their nets and their eyes unbrown, colored blue and grey and green like the river bottom as it crawls slowly and ponderously to that old and open sea. The ones who never pick all of the crop—who always leave the roots—who always know how much nature can give. How much nature can take.

Once a year, they strip the trees of their sticky, paper bark in long rolls like scrolls in Nibutani; cut across the trunk, slender blade to teasing, and then the strip rips upward like a lit line of oil. Tug, slack, tug, slack, strip, and peel. They know which way the wood goes, which knots interrupt the line, which grooves will yield. Till they have strips of trees, sashes flowing and tinkling in a soft mother wind. The trees wear clothes, they say. Thank you for sharing your clothes. Then they peel. Never taking all of it, so that the trees can live. That is the culture.

Theirs is the keeping of life. The stories of the gods of greenery, the names of the wild plants in Hokkaido that have no names in Japanese. The people who believe in the spirits of everything; the kamuys. The animists. The keepers.

And now? They’re dying softly. Only 24,000 left on those northern shores. Halved in just the last decade. 97% assimilated. Some sources say there are fewer than ten fluent Ainu speakers left— all over sixty-four years old.

I don’t know why I’m so compelled by them. We have no real connection. Perhaps it’s the depth of their spirituality—or the shallowness of mine. Maybe it’s something I’m missing.

But maybe, in part, it’s because I know that despite their best efforts otherwise—the committees, the language lessons, the publications, cultural centers, Sapporo Pirka Kotan, victory of recognition (finally) from the Japanese government just three years ago as an indigenous people of Japan—they’re fading. They’re watching it happen. We’re watching it happen. And still, they’re making the efforts anyway. The old woman in this photograph is smiling at me.

I stare at her—struck by a yearning, a need to know what she knows.

Where did you come from? How can you bear knowing what’s going to happen? How do you say goodbye?

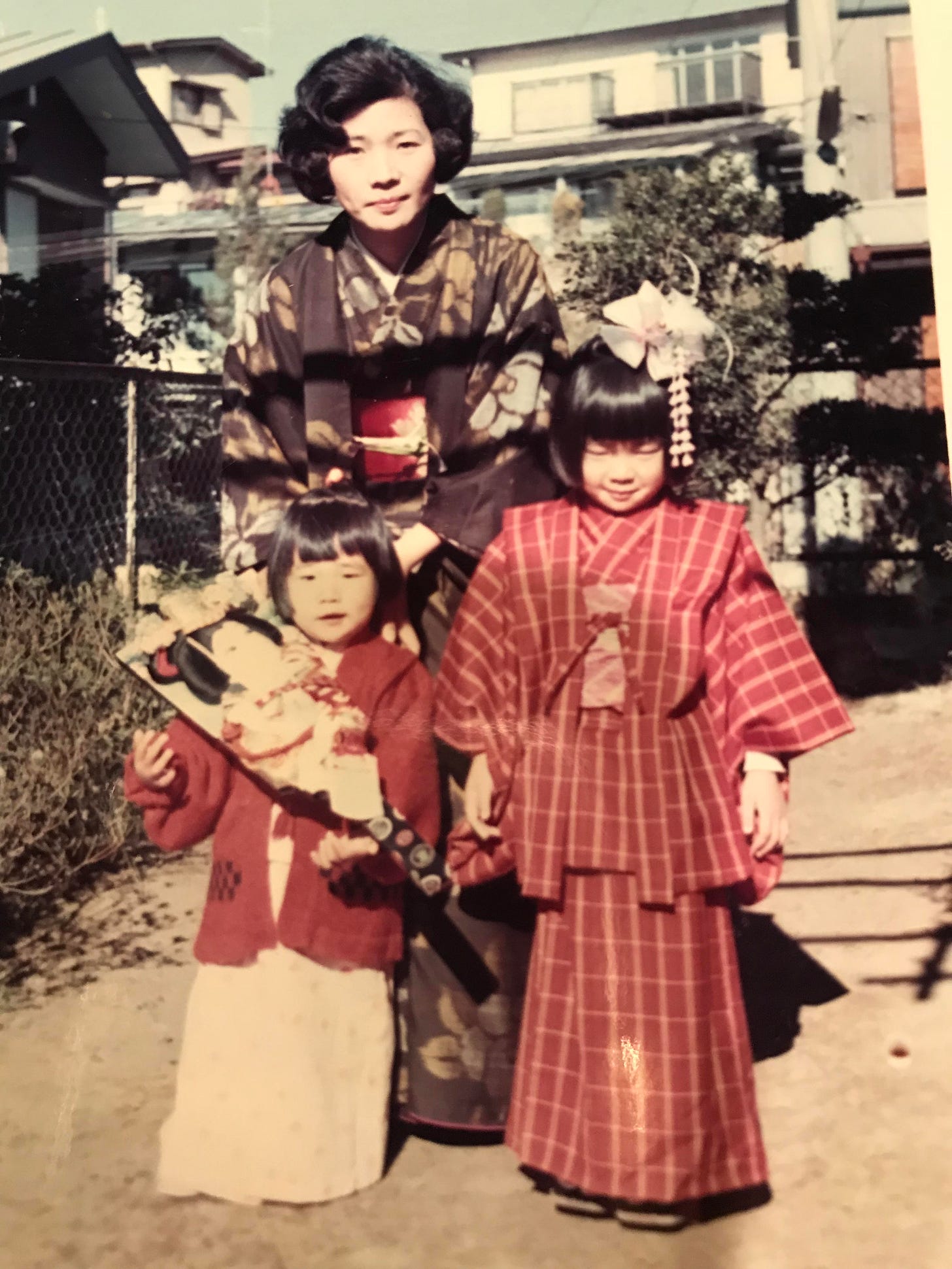

The minute I was born, it started dying for me too. My heritage. It wasn’t a fight so much as a realization that I wasn’t going to be able to hold it. What chance did I have to keep misty mountains and lettered stones? Me with my western hands, western education, western religion. As the years pass, I lose our words through my fingers like sand—fushigi, daidokoro, kiseki— misplacing stories, forgetting phrases. Street signs. I wake up one day and realize I can’t remember how to get to Baba’s house from Mitsukyo Eki. The smell of green tea fields in Shizuoka; my grandmother’s clothes—kinmokusei and smoke.

Most of my life, I’ve been here. Twenty-four years in America. Only two in Japan. And something in me understands that it was always a choice and also wasn’t. That even as I knew I could move back at any time—longed to, even—I was never going to. All the dreams I was chasing were tied here—irrevocably, leaf and bind, to this land.

From where I stand, I realize more and more the stakes of those decisions. The longer I’m here, the more American I become. Burying my culture. Choosing a side—sticking to it.

I have nightmares that I forget my mother’s face.

And I know that despite my book learning, my kanji classes, my efforts to make gyoza and udon, to return to Japan, to be storied by my mother and grandmother, it won’t be enough. That eventually, I will forget. My sisters and I, we will forget. The shiseido smell of our mother’s face. The pucker taste of the last batch of umeboshi our grandmother made. The weight of the lionhead door knocker in our hands.

It’s not a shame that it’s happening. It’s happened everywhere, the stamp of time across history’s back. It’s only a shame that we have to watch—that we have to watch our culture quietly panting, disintegrating underneath that rock. That we can’t turn from it, because we’re family. Obligated to witness.

I click to enlarge a picture of a beautiful young Ainu woman, reimagined by an artist in color from the original black and white. We always forget that colors were just as bright back then. Jokes just as funny. That good food tasted good—really good. That everyone had secrets, just like we do. And that love was still hoped for— still as unfathomable and beautiful.

Most of all, we forget that our own descendants will also forget this, just like we did. That the colors of their culture, long past, were just as bright, the stories just as vivid. They’ll forget that steam moves now as it did then, shifting and canting towards the sky.

Anticipatory grief. What a waste of time, my Baba would say. And I agree, for the most part. Science is split—some submit that it can actually mitigate the pain of grief post-loss. Others say it has no effect. My American side thinks it’s healthy— that it can help you live better and relieve depression. My Japanese side is my grandmother’s voice. And ironically, my own pain.

Did you know that language actually changes the shape of your face? The smallest variations in the shape of your vocal tract amplify, across generations—different muscles, different wrinkles, over time. I hope it won’t change mine. But that’s like the stones asking the river to not do what it’s made to, to be what it is not.

On some days of quiet lostness, when I’m homesick and unfound, I look into the mirror and will her to come out. My Japanese self. I want to see if she still can. I lean in closer with American determination. Come out.

It takes a moment, but I see her, occasionally. In the Misono nose I inherited from my grandmother. In the roundness of my cheeks from her mother. The longing growing old in my eyes: resignation. Shouganai. It can’t be helped. I see Fudé, my great great grandmother geisha who must have been scared to leave her hometown of Kyoto to marry the Lord of Kago but did it anyway. Itsuka Obasan, her house by the sea where she raised her child alone having left everything else behind. Hidé, the mother my grandmother never got to know because she died giving birth. The mother she rarely talks about because she thinks it’s a waste of time. But when you ask, she takes an hour to fill you with mother memories she’s gathered from neighbors and sisters—stories she’s carefully collected and saved.

They hold hands and circle around me. They don’t clap, but their music takes me home. They don’t prevent the loss because they can’t; but they mourn with me.

The Ainu tattoo their lips. For beauty, and as a talisman—a ward against evil spirits. A mark of being a woman. Of being human.

I don’t know what I’m supposed to do while I watch it drain; where I should put the grief of this impending loss—burying my dead before they’re dead to save me the grief of the happening.

The Ainu have bear huts. Each season, they take two bear cubs and raise them as family members. Feed them the salmon they catch, the same they eat, those salty pink slivers cut from the bodies of their brothers. Sense that other world in that warm, brown fur that smells of nettle; the other side of the mountains under tender padded paws and tongues that know which tastes are life-giving and which are life-taking. Raise two bear cubs as family members; one they kill to eat, and one they send home—back to those smoky and magisterial woods, to the mothers who made them.

What we keep and what we release. What we have to release—for survival, for life. Never taking all.

I want more answers. And relief. But I only have this old woman to sit with. This woman, this old woman, smiling at me from the photograph. Still passing things on, as if they were going to survive—as if she was going to live to see them happen again. The cap on her head, with the intricate embroidered design that weaves through, colored and bright. Full of wrinkles and wisdom. Eyes old as oceans. With the smile of someone who understands something. But doesn’t tell you.

The Ainu know the runs of trees—their lengths, their tales, their quivering. They know the wind and its whistling, the fish giving way to the fisher, the animals that die for their living. Life giving way to life. They know the tundra and the sun with its pale gold lips that press it, melt it, balance it all.

Deep and knowing, her eyes don’t speak. I wait—listening for an answer.

Moe Graviet is a poet and essayist currently studying at Yale Divinity School.

Moe, what a pleasure to read. I hope your descendants delight in and ponder the beautiful way in which you live your life in harmony as you do the life of your grandmother and the Ainu. I like to believe our heaven will include a resurrection of perfected culture as well as body.

I'm returning to this essay as I'm visiting the Pacific, the land of my ancestors, for the first time in many years. I find myself caught in the same cultural currents so well described here and I'm glad to have a fellow traveler to help me think so beautifully about that!