Note: This is a choose-your-own-adventure post. If you’re in the mood for some practical application, take ending 1. If you’re game for some abstract theology, take ending 2.

To read Genesis 5 alongside Moses 6, Joseph Smith’s revelatory revision and interpretation of the same biblical text, is a study in contrast. The text from Genesis, a lineage of ten generations from Adam to Noah, is terse, formulaic, archaic, and enigmatic. The text from the book of Moses is expansive, creative, and explanatory.

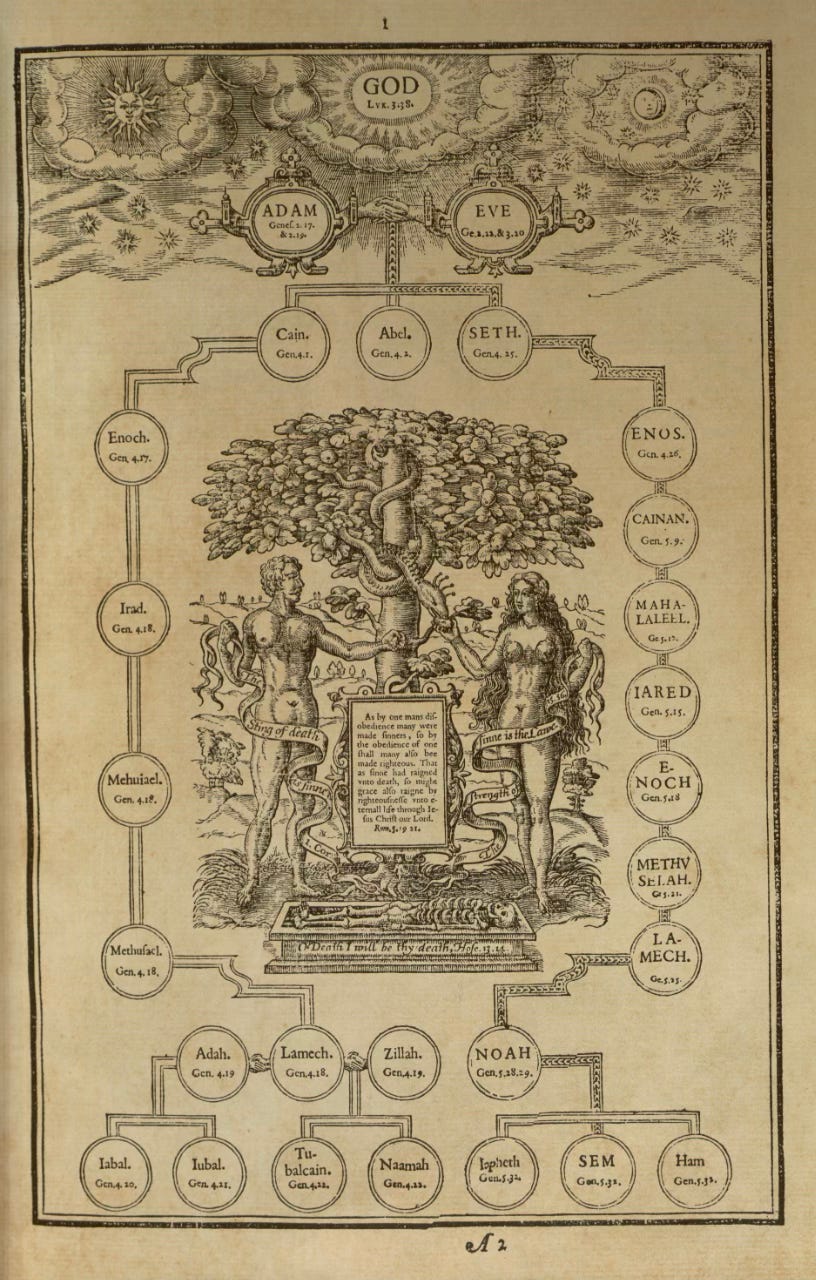

This is not, of course, to say that the Genesis text isn’t rich with meaning. In the book of Genesis, genealogies like the one in chapter 5 are “carefully placed compositional units that mark off one large narrative segment from another.” Here, the genealogies signpost the period from the Flood back to the Creation, which is recapped in the first verses: “In the day that God created man, in the likeness of God made he him; male and female created he them; and blessed them, and called their name Adam,” or “humankind” (Genesis 5:1–2). The ten subsequent genealogical entries follow a four-step pattern, each step echoing some aspect of the Creation story: first, the father’s begetting and naming of a son “in his own likeness, and after his image” (Genesis 5:3) recalls God’s creation and naming of humanity; second, the father’s subsequent lifespan reflects God’s first blessing on the human family; third, the note of additional “sons and daughters” (Genesis 5:4) fulfills God’s command that Adam and Eve multiply and fill the earth; and finally, the statement of death (Genesis 5:5) confirms God’s decree that humankind must “surely die” (Genesis 2:17).

It’s tempting to gloss over Genesis 5, but if we read carefully, we can find in it the ancients’ own reflection on the values imbued in the Creation. The genealogy from Adam to Noah shows that a thread of creation’s original structure persists after the Fall in the procreative powers of men and women who impart to sons and daughters their birthright as image-bearers of God. Ordered cycles of birth and death preserve across time humanity’s inheritance of the divine nature. God appears as a benevolent father who works to ensure his children’s future well-being.

It’s true, however, that the repetition can get numbing. Formulaic language makes any difference stand out starkly, so it’s no surprise that readers perk up at the anomalous—and cryptic—report that Enoch “walked with God” until the moment that “he was not; for God took him” (Genesis 5:24). The verse reads as a teasing glimpse of some lost tradition, and it has fired readerly imaginations for centuries. Jewish apocalyptic literature interpreted Enoch’s mysterious removal in elaborate narratives of heavenly ascent and cosmic visions.

Joseph Smith’s revealed expansion of the Enoch figure in Genesis 5 also elaborates on the prophet’s mysterious departure from earth. It becomes the focal point for both the Restoration’s theology of Zion, the righteous city that God preserves from a degenerate world by removing it wholesale until the building of its latter-day counterpart, and the Restoration’s concept of “translation,” which draws together textual translation with the miraculous traversal of time and space. These are among the teachings I most cherish in our religious tradition.

Still, though, we ought not pass too quickly over the other mysterious statement in Genesis 5: that Enoch “walked with God” on earth. In Moses 6, how is that phrase cashed out?

The narrative opens on Enoch journeying out of his father’s land in Cainan, when the Spirit of God descends upon him and a voice from heaven calls him to prophesy. Shocked, Enoch confesses his weakness and questions the call, but the Lord reassures him that he will be given the words he needs: “Behold my Spirit is upon you, wherefore all thy words will I justify; . . . and thou shalt abide in me, and I in you; therefore walk with me” (Moses 6:34). The Lord instructs him to anoint his eyes with clay and then wash them clean; in this way, Enoch becomes a “seer” who is able to see God’s primordial spiritual creation at work in the physical world. Thus prepared, Enoch teaches the people from their ancestral book of remembrance the truths God revealed to their earliest fathers: that Adam and Eve fell to make mortal existence possible, but that the world has turned away from God. Happily, every person can return to God’s presence through belief, repentance, and baptism in the name of Jesus Christ, receiving thereby a new life that abides in them by the Spirit. So it happened for Adam, who was buried and rose from the water a new person; and “thus may all become my sons [and daughters]” (Moses 6:68). This plan of salvation, Enoch emphasizes, must be freely taught from generation to generation.

The material in Moses 6 is packed tight with narrative and theology, but one way to unify its central message is to use the Gospel of John as a lens. Enoch’s experience has many connections to the fourth Gospel, from the Spirit that descends and abides on him as it does on Jesus at the beginning of his ministry (see John 1:32), to the anointing of his eyes with clay in the way Jesus anoints the blind man (see John 9:6), to his teachings about the new birth by the Spirit that resemble Jesus’s teachings to Nicodemus (John 3:5–8).

But perhaps the most striking connection to the Gospel of John is the promise that we can abide in Christ, and Christ in us, by means of the Spirit: “Behold my Spirit is upon you . . . and thou shalt abide in me, and I in you; therefore walk with me” (Moses 6:34). This theology of divine “indwelling” is the most distinctive—and challenging—of the fourth Gospel. It’s as if Moses 6 interprets the most mysterious phrase in Genesis 5 (“Enoch walked with God”) by way of the most mysterious concept of John 15 (“Abide in me, and I in you”).

Yet, as happens so often in scripture, iron sharpens iron. The encounter of two ideas makes both of them signify more. Here’s where you get to choose your ending:

Ending #1:

As abstruse as the idea of “indwelling” can sound, the Gospel of John explains it in a practical way. When we keep the commandments, Jesus explains, we are doing the will of God. And since God’s will is inherent in God, we might say commandment-keepers are in God and God is in them: “If ye keep my commandments, ye shall abide in my love; even as I have kept my Father’s commandments, and abide in his love” (John 15:10, emphasis added). But “abiding in God” does not mean we are insulated or isolated from the world. Perhaps surprisingly, being in God turns us outward toward other people. Jesus explained this, too: “A new commandment I give unto you, That ye love one another; as I have loved you, that ye also love one another” (John 13:34). When we keep Jesus’s commandment to love, we become one in him and we are turned outward toward others.

This is precisely the move that Enoch illustrates in Moses 6. Through his willing obedience to the prophetic call, Enoch abides in God, and God in him, through the mediation of the Spirit. He then immediately turns to the loving work of proclaiming the gospel to the world. His ceaseless preaching, teaching, baptizing, and Zion-building are only possible because of his sustaining, abiding relationship with God by way of the Spirit. To “walk with God,” Moses 6 teaches us, is to abide in God and then join God in his work of love.

Ending #2:

Moses 6 explains that Enoch walks with God because he abides in God and God in him—and that this is only possible by the mediation of Spirit: “Behold my Spirit is upon you . . . and thou shalt abide in me, and I in you; therefore walk with me” (Moses 6:34). The Spirit (as personage) is the agent of God’s indwelling in Enoch. But “spirit” (as quality) is Enoch’s capacity to receive the indwelling divine presence. In other words, my “spirit” is the name I give to the openness of my being to God. The Spirit dwells in me because I am spirit—that is, because I am the kind of being whose basic fabric is open to God.

This, I take it, is what’s at stake in Moses 3’s revelation that “the Lord God, created all things . . . spiritually, before they were naturally upon the face of the earth” (Moses 3:5). Spiritual creation isn’t merely a prior event in a sequence, like the blueprint for a building. Spiritual creation is the constitution of all things made with this openness to God. To be created spiritually is to be created as capable of receiving God. I was made for indwelling.

In Genesis 5, where we began, each father begets a son “in his own likeness, after his image,” passing on the birthright of divine image-bearing. Now we can see what that birthright is: our fundamental openness that makes it possible for God to dwell in us through the Spirit. What persists through the generations is spirit itself, humanity’s ability to receive the very God who made us for “immortality and eternal life” (Moses 1:39).

Rosalynde Frandsen Welch is Associate Director and a Research Fellow at the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship. Her research focuses on Latter-day Saint scripture, theology, and literature. She holds a PhD in early modern English literature from the University of California, San Diego, and a BA in English from Brigham Young University. She is the author of Ether: A Brief Theological Introduction, published by the Maxwell Institute, as well as numerous articles, book chapters and reviews on Latter-day Saint thought. Dr. Welch serves as associate director of the Institute, where she coordinates faculty engagement and co-leads a special research initiative.

Art from King James Bible (1611).