Cherry Twizzlers and the Joy of Unexpected Grace

If ye then, being evil, know how to give good gifts unto your children, how much more shall your Father which is in heaven give good things to them that ask him? (Matthew 7:11)

Cattle never seemed far from my dad’s mind. We might need to take the cattle hay, check on the windmill to make sure the cattle had water, drive out to see if it had rained, or inspect the fence line. Or we might simply need to “go out south” for the sake of “going out south.” “Out south” was the southern Utah term for the Arizona Strip, the desolate and thinly populated region of Arizona that lies north of the Colorado River.

As a boy, I didn’t really care for the trips out south with my dad. They felt long, boring, and dusty.

Depending on what a given day’s agenda entailed, my mom might pack a lunch for us and send us on our way. If it was a quick trip with an early start to avoid the heat, and we planned to be back home before lunchtime, we’d just head out south with no thought of food or snacks. Sometimes both my brother and I accompanied my dad, and sometimes just one of us went along.

During the long trips my dad would hardly utter a word. We’d drive in silence, complete the given task, and return home in silence. We didn’t listen to the radio either. He might sometimes break the monotony of the drive with a sudden exclamation, “Have you ever had a horse bite?” as his large hand would land on my leg with force. He’d wrap his grip tightly around the inside of my leg and squeeze with too much vigor. It hurt, and that was the point. He’d laugh at my reaction and then he’d withdraw back into stony silence. I sometimes wondered what he thought about on our trips out south, but mostly I matched his silence with my own as I stared out the window, watching the scenery go by.

Nearly fifty years later, the various trips out south blend into each other. Silence and work. Work and silence. When I reached my early teenage years, as soon as my dad would turn off the paved road onto the long dirt roads leading to one piece of ranching property or the other, he would pull over and offer to let me drive. This was years before I turned sixteen. I drove tractor for my brother’s hay hauling team in Hurricane, so there was no reason not to let me drive on the dirt roads to the ranching land in Arizona. I don’t recall my dad ever giving me much of a driving lesson, just the basics, and then he let me drive. I enjoyed the thrill of it. I’d go plenty fast, and if he ever said anything at all, it might be something like, “Walt, you ought to slow down a little.” He was never mean or bossy about my driving. He was never controlling or worried. He seemed perfectly content to let me drive. He mostly sat in silence, watching the sagebrush go by. Driving broke up the monotony of the trip and gave me a sense of control over how long it might last. If I drove fast, we’d get home sooner and then my time would be my own.

There were occasions when my dad’s eagerness to see if it had rained or see if a recent storm had run water into the ponds would overpower his good sense and wisdom. He’d drive into a muddy wash and get stuck. At such times we’d then walk in silence the ten miles or so from our land in Pipe Valley over to Cane Beds and hope that one of the few families that lived there would be home so that we could use their phone and call for help. Even still, my predominant memory of what must have amounted to hundreds of trips back and forth between Hurricane and out south is one of silence and work; work and silence.

But one particular trip out south continues to captivate me and stand out from the rest. I can still taste its sweetness in my mouth, and the memory of it sometimes escapes from the corner of my eye and rolls down my cheek. I do not recall the purpose of the trip or any particular circumstance other than that I was alone with my dad in the big cattle truck. It was old and dusty, and there were always leather gloves and spurs and braided tie ropes scattered about. A single blue-vinyl bench seat dominated the interior and stretched the length of the cab. Because I was alone with my dad, I enjoyed the majority of the bench seat to myself. I perched in the middle where I could slide around in unbuckled innocence or take a nap or stare out the window in awe of the beauty that surrounded us. I likely anticipated a horse bite or two at some point on the journey, but mostly I settled into the silence of the drive. It is difficult to be sure how old I may have been, but my guess is eight or nine.

We rarely stopped at Colorado City for anything, usually passing it by. On this particular trip, if my memory serves, we stopped for gas. I stayed in the cab of the truck while my dad filled up and then went inside to pay. When he returned, he surprised me. He handed me a personal-sized pack of Twizzlers Cherry Nibs licorice candy. I don’t recall him speaking, but somehow I came to understand that that particular pack of candy was mine and mine alone. I did not need to save any for my brother or sister or mom at home. I did not need to share with my dad either. The entire pack was mine.

The feeling of that moment will likely stay with me for the rest of my life. The man I associated so much with silence and work, work and silence, with hard hands and a quick temper—that same man had gone into the store, thought about me, purchased a small pack of Twizzlers Cherry Nibs, and given it to me. My mom took care of food and drinks and fun; my dad took care of work. He certainly did not think about sweet treats or about kids. Except on this day, he did. It was a revelation to me. It was a dose of grace infused with cherry and filled with licorice goodness. I felt as if that dusty cattle truck had just been sprinkled with fairy dust, and everything in the world became magical. The wonder of that moment can fill me with awe. My dad remembered me for no other reason than for the hope that I might have joy. I opened the pack of nibs and savored each one. They tasted like love to me.

When I’m at a rest stop on a road trip of my own, or when I wander into the candy aisle of a grocery store, I sometimes find myself scanning the dizzying selection of treats for Twizzlers Cherry Nibs. When I find them, I buy a pack and savor the sweet taste of love that waits inside. I think about going out south with my dad, the blue vinyl bench seat, the dusty cattle truck, and the joy of unexpected grace.

W. Paul Reeve is the chair of the History Department and Simmons Chair of Mormon Studies at the University of Utah where he teaches courses on Utah history, Mormon history, and the history of the U.S. West. His book, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness, (Oxford, 2015) received three best book awards.

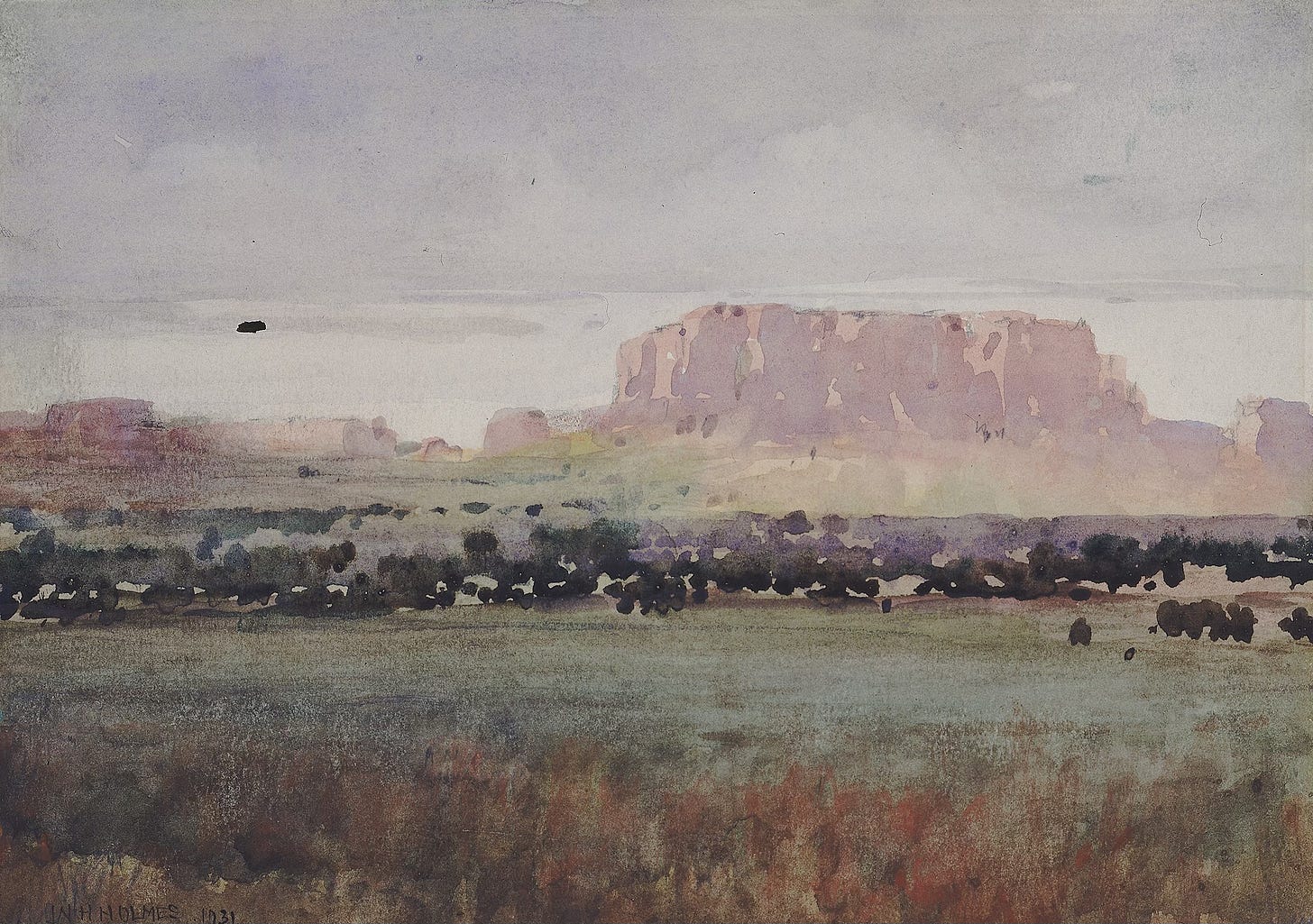

Art by William Henry Holmes.

I loved reading this poignant remembrance. I was raised on a ranch as well and trips with my Dad are memories full of power beyond the simple tasks we were doing. Thanks for this.