I have been a student of C. S. Lewis for as long as I have been a reader. His Chronicles of Narnia were some of the first books I stumbled haltingly through when I first transitioned from reading phonetically to reading for pleasure. As I hid in closets and behind couches reading my mother’s 1970s editions, I longed to go to Narnia, this land where children became heroes by showing virtue and courage. There was just something about being in Narnia that felt immediately right to my soul. I completely failed to notice any of the Christian symbolism of the books. When it was pointed out to me while I was still quite young, I felt as if I had been tricked, that the adventures I had enjoyed were somehow cheapened because they were “really” about something else.

My thoughts about symbolism have changed somewhat over the years. While studying literature as an undergraduate, I realized that only the poorest symbols were merely one thing standing in for another. The symbols crafted by the greatest writers stood for entire stories and went on to become used in other texts as shorthand for a larger experience: Oedipus Rex, Hamlet, and Atticus Finch, for example. In this way, fiction often captures truths greater than the factual realities of nonfiction.

However, my mind was still tainted with the idea that the Narnian Chronicles were the other sort of fiction, a transparent allegory with poor and incoherent worldbuilding meant for children who didn’t know to expect better. Perhaps some of this thinking was borrowed from Philip Pullman, author of the rival children’s series His Dark Materials who famously dismissed Narnia as “propaganda.” But whatever way it happened, I came to believe that though Lewis was a first-rate apologist and critic, he was a poor fiction writer. Oh, certainly, The Screwtape Letters and The Great Divorce were excellent in their own way, but they merely proved the point that Lewis was much better at allegory than he was at genuine fiction writing. Of course, I avoided actually rereading the Chronicles of Narnia to find out if this hypothesis was true. I didn’t want to trample on what remained of the magic I had felt as a child.

When a recent perusal of an audiobook sale turned up Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C. S. Lewis, I was intrigued enough to add it to my library. A revolutionary book in Lewis studies published in 2007, Planet Narnia held out for me the hope of an innovative interpretation of the novels, one that might restore my childhood experience. Yet I dithered and delayed. I was afraid that the argument wouldn’t hold together, that I would once again be let down.

The moment for reading finally came when our family was on a Church history road trip, driving from Utah to New York and back again. In the middle of the Great Plains on a Latter-day pilgrimage to the Kirtland temple, I found myself driving without anything to listen to. My kids were all busy with video games, and my husband was reading on his Kindle. I flipped through a few podcasts, tried to pick up the work of classic literature that I’d been slogging through for months, then put on the speculative fiction novel I had recently started, but nothing seemed satisfying. As I furtively scrolled through my audiobook catalog while keeping one eye on the unchanging highway surrounded by corn fields, I decided to give Planet Narnia a shot. It seemed a strange choice even to me—who listens to literary criticism to stay awake?—but I was desperate for something, so I pushed play.

The Kirtland temple, the first of the Restoration, can seem alien to even the most experienced temple attender, as different from our typical temple experience as other temples are from our Sunday worship. This temple has no creation room, no celestial room; it feels more like a church than a temple. I wonder if the early Saints were confused about why they were commanded to build it. They came from a culture that assumed the need for a temple had ended with Christ’s resurrection. Were they as baffled by this first temple as many Latter-day Saints are by their first temple experience?

Attending the temple for the first time is a threshold moment in the life of a Latter-day Saint. When I was preparing for my endowment, people around me began sharing stories of how different the temple would be. A sister in my parents’ ward had come out of her endowment feeling so bewildered that she immediately went back in for a second session, determined to show the devil that he couldn’t make her doubt. My future father-in-law warned me that many people felt strange about how different it was from our typical worship services and that I should go into it without preconceptions.

I was surprised to find that my experience was completely different from anything I’d been led to expect. In the temple, I felt at home.

In sacrament meetings, talks seemed to endlessly repeat basic principles, adding little to a generic outline of the gospel. In Sunday School classes, people simplified the scriptures until they were mere outlines pointing to a moral lesson. But the endowment skipped this sort of direct teaching. It focused instead on an experience, a story with symbols. Just as when reading a novel, in the endowment, we are asked to ally ourselves with the protagonists of a story—the story of humanity—and accept their experience as our own. As Adam and Eve experience the creation and the paradise of Eden, their fall and their redemption, we experience it along with them. The temple let me sit in that story without feeling a need to explain anything. Indeed, I became a part of it.

For similar reasons, I always loved the war chapters of the Book of Mormon because they let me sit with the characters and their motivations. I was baffled when others complained that there was so little of value that they had to slog through the second half of Alma and all of Helaman to reach 3 Nephi on the other side. For me, those chapters were the most narrative—and therefore the best—chapters in scripture. Sure, I couldn’t practically apply Nephite war strategy in my life in any but the most metaphorical ways. But I could glimpse the twisted logic of self-justification through Zerahemnah's speech and feel through Moroni the power of righteous anger and the abashedness of finding it misplaced. Those chapters were aflame with an atmosphere of utterly crucial moral choices. I learned more about living a moral life by breathing their air than by any sermon contained in the book because I could learn, if not from my own experience, then at least from secondhand ones.

We’re more likely to enjoy this kind of immersive story in a movie theater or the pages of a book than we are on our spiritual journey—perhaps because we’re more likely to consume pop culture stories all at once, whereas our experiences of the sacred texts are meted out in weekly installments over the course of years. Few of us are binge-reading the scriptures, and even fewer of us are experiencing the scriptures as its intended genre of story or poem rather than a book of doctrine and wisdom. As C. S. Lewis put it in An Experiment in Criticism, his analysis of different ways of reading, we are more likely to “use” the scriptures to further our own thoughts than to “receive” them on their own terms. The opportunities to really surrender ourselves to the text, as Lewis says attentive readers must do, seem to be few and far between.

Was it always this way? No doubt there has always been proof-texting and inspirational reading, but the early Saints seemed to have understood the importance of inhabiting stories better than we do now. A year ago, when recent changes to the temple ceremony made me curious about past adjustments, I picked up Devery S. Anderson’s Development of LDS Temple Worship, 1846–2000: A Documentary History. A compilation of diary entries, letters, First Presidency notes, and Church handbooks concerning the temple, the book shows the evolution of our understanding over time. One thread in particular I noticed was that it was not until recently that leaders began to comment on the difficulty of teaching young Church members to understand the temple. Later, these concerns become a large part of the discourse, but in the early documents, Church leaders instead worry about keeping the Saints from joining other secret societies and prioritizing them over the temple. It seems to me that the prevalence of things like freemasonry in the American culture of the time gave the early Saints a framework for understanding the symbolic experience of the temple that we have no parallel for today.

Except when we talk about stories.

This is where Michael Ward’s analysis of the Chronicles of Narnia comes back in. The type of fantasy fiction that C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien wrote has come to be referred to as “mythopoeic fiction.” In mythopoeic fiction, the author acts through narrative to create a new mythology, a new symbolism, which has spiritual significance both to the characters and to the readers of the story. This type of fiction is deeper than an allegory; each character doesn’t just stand for some attribute, enacting a moralistic tale. When mythopoeic stories succeed, they are as resonant as those of authentic mythology.

As I drove my family down the highway towards the historic Kirtland Temple, Michael Ward’s analysis opened to me his version of the mythopoeic meaning of Narnia. If this wasn’t exactly the same wonder I had felt as a child, it was certainly like unto it. In Planet Narnia, Ward argues that the series was crafted to renew the medieval symbolism of the seven planets of the medieval cosmos. This symbolic structure for the universe—which in turn was a repurposing of Greek and Roman mythology by medieval Christians—was being lost in modernity’s more scientific ways of looking at the universe. Lewis felt our modern imaginations were poorer for the loss of these potent symbols, and so, Ward argues, he set about constructing a new version of these symbols for the modern imagination, reforging their meanings in the same way as they had been reframed by Christian scholars of old.

Rather than depicting the gods and the planets they symbolize directly, as Lewis did in his poem “The Planets” and in his science fiction trilogy, Ward argues that the Chronicles instead attempt to bathe the reader in the overall symbolic atmosphere of each of the planets. Lewis himself used various terms to capture this idea of a symbolic atmosphere in his own scholarship—“‘a state or quality’; ‘flavour or atmosphere’; ‘smell or taste’; ‘mood’; ‘quiddity’”—but Ward coins a new term for this writing technique as Lewis wields it. He calls it “donegality” after a quote from a letter Lewis wrote on the subject referencing a region in Ireland that Lewis loved:

Lovers of romances go back and back to such stories in the same way we go ‘back to a fruit for its taste; to an air for . . . what? for itself; to a region for its whole atmosphere—to Donegal for its Donegality and London for its Londonness. It is notoriously difficult to put these tastes into words.’

In Ward’s parlance, donegality means “a spirit that the author consciously sought to conjure, but which was designed to remain implicit in the matter of the text.”

In other words, each of the Narnia books explores the relationship between man and God through one of the medieval “seven heavens,” all spiritually showing different sides of the divine nature, with an atmosphere that would evoke the same symbolism that medieval people felt at the mention of Mars or Saturn. The goal was not to teach about these symbols, but to write a world and a story that would allow modern readers to experience and thus understand them.

For me, driving down that midwestern highway, Ward’s explication of the spirit of the first Narnia book, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, struck like a thunderbolt—aptly, since Ward’s symbolic ruler of the novel is the spirit of Jupiter, otherwise known as Jove or Zeus. In medieval thought, he is the king of the gods; his spirit is one of benevolence and plenty, of joviality, the kingdom at peace and the banquet table prepared for his loyal followers. Ward was first tipped off to a possible connection by a line describing Jove in Lewis’s poem “The Planets,” which reads like a plot summary of the first Narnia book: “of wrath ended / and woes mended, of winter passed / And guilt forgiven.” Others have remarked that seeing the book through this lens makes sudden sense of one of Lewis’s most cited egregious errors against believability: the presence of Father Christmas in a fantasy world of dryads and fauns. He is the ultimate modern embodiment of kingly celebration, of peace and plenty, the spirit of Jove, and so his place in the story makes sense symbolically, though Tolkien objected to his presence from a worldbuilding perspective.

But this was only a small piece of the understanding brought by seeing The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe through the lens of Jupiter. As Michael Ward explained the various symbols of Jupiter present in the novel, I understood the story in a way I had never seen it before—or at least, in a way I hadn’t seen since immersing myself in it as a first grader. Focusing on the kingly aspects of the plot suddenly reveals the journey of the four Pevensie children as one of divine ascent. Lucy and Edmond both fall into the land of Narnia by partaking of forbidden food (tea with the double-crossing faun Tumnus and the White Witch’s Turkish delight), leading them into a confrontation with all that is wrong with this fallen world. From there, the children progress first by learning about Aslan, then by meeting him and committing to aid him in his recovery of Narnia. After they are redeemed from their fallen state by an atonement, they devote their very lives to the recovery of Narnia. In the end, through their faithfulness to Aslan, they are crowned kings and queens to rule under him in benevolence and peace.

I suddenly realized that the story described through the essence of Jove began to sound exactly like the stages of the endowment.

Was the reason I felt at home in the temple because of the stories I had read as a child? Narnia, among other heroic fantasy novels, taught me this pattern of ascent towards the divine, popularized by Joseph Campbell as the hero’s journey. A person naturally started as an ignorant farm boy or girl, fell into a world of evil almost by accident, and gradually learned through experience and commitment to become the hero that the gods needed to fulfill their plans. Is it possible that so many are confused by the temple because we are so used to a religious environment that focuses on an analytic search for meaning rather than on the experience of divine growth? I began to see that the temple might not be about learning specific doctrines or specific knowledge, in spite of the tendency to focus on the sacred tokens and signs acquired there. Perhaps the whole goal of the endowment is to experience the inherent quality of this mortal journey—to help us see, or more importantly feel, the bigger picture that God has for our lives.

As my family pulled into Kirtland and onto the street where the temple sits, I was awed by the humbleness of the building that represented the beginning of this experience for the Latter-day Saints. Though the Kirtland temple never saw the administration of the modern endowment, it is where this holy atmosphere started. The sense of scale, captured by the endowment, was first present here, where a group of converts strove to accomplish in a small community that same feat which took medieval people centuries: the building of a sacred structure to give people the atmosphere of the divine.

In the end, it doesn’t matter whether you buy that Lewis intentionally crafted the Narnia books with the seven heavens in mind or you think that Ward has merely stumbled upon an interesting way to reread the series. The intentionality (or not) of the structure doesn’t take away from the experience of the novels. After all, as a review of Ward’s work noted, “children are not carried away by Lewis’s plots, still less by his Christian allegories. What stays with them, rather, is the imagery: a faun carrying his umbrella through the snow, a lantern in the wilderness, a statue coming to life.” Similarly, perhaps we don’t need to spend our time analyzing the endowment, trying to come to conclusions about what is symbolic and what those symbols mean. Perhaps the best way to understand the temple is to simply exist within the experience, to consider ourselves as if we were Adam and Eve. Maybe, more than any direct doctrine or critical message, this is what the temple wants from us: a feeling, an atmosphere, a taste of our Heavenly Father’s hopes for his children, an emanation from our heavenly home.

Liz Busby is a writer and scholar currently doing graduate work at BYU on intersection between Mormonism and science fiction/fantasy. Her writing has been published in BYU Studies, Irreantum, and SFRA Review.

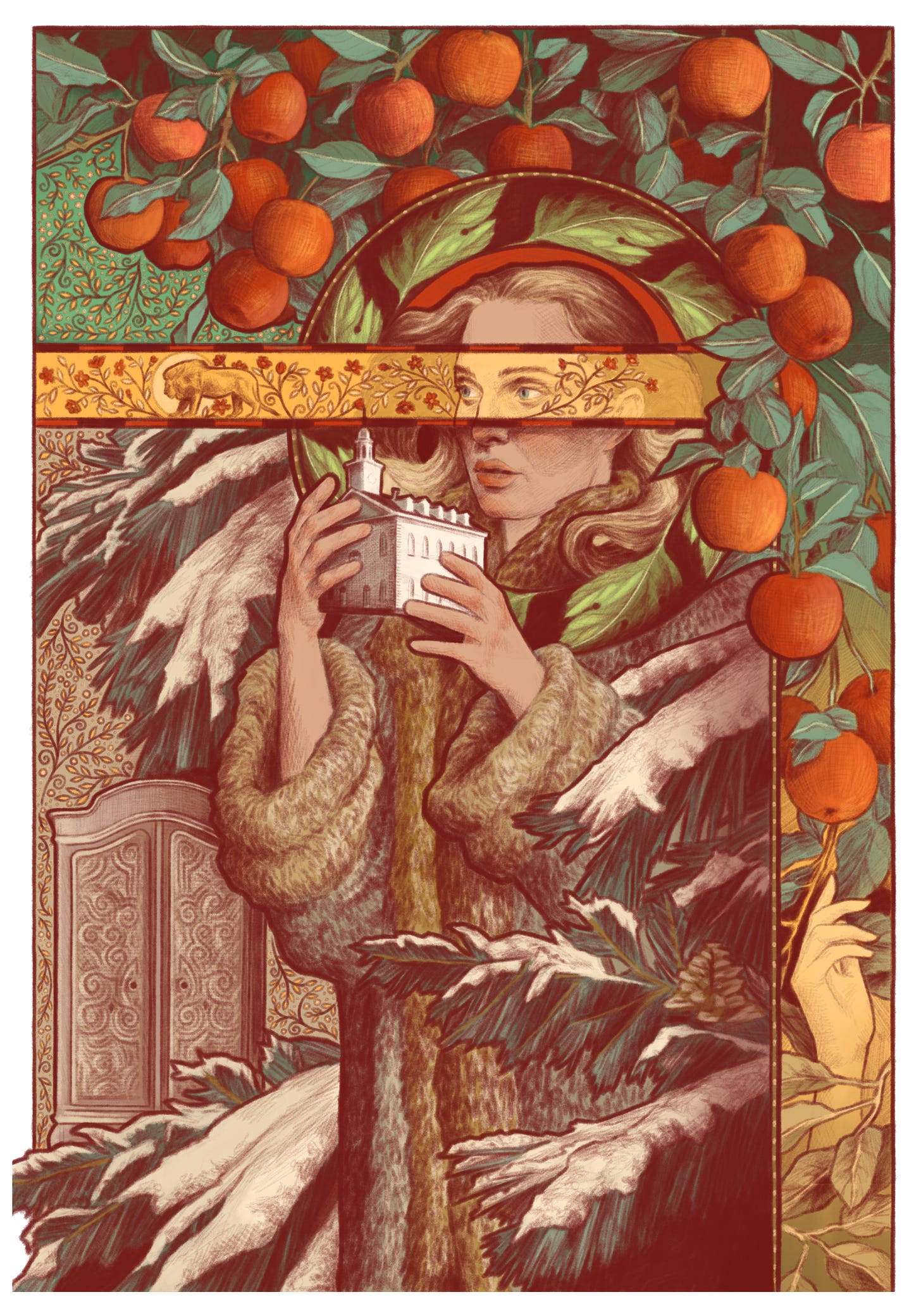

Art by Jessica Sarah Beach.

Wonderful. Thank you for this. I find by inhabiting the story, I often begin to see different symbolism.